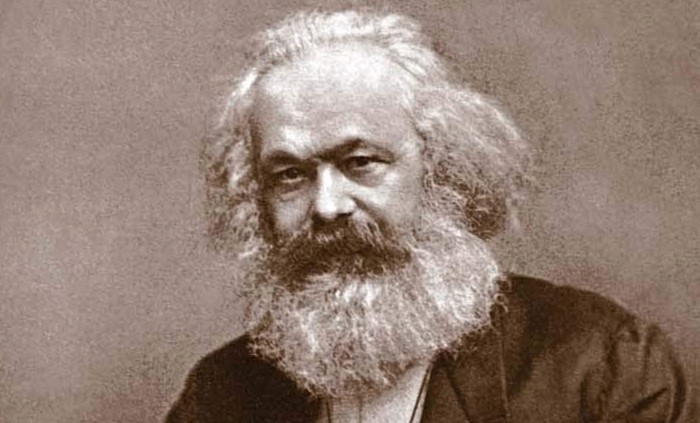

Marx writing in 1873 against Proudhonism and Italian Bakuninists favoring political abstinence for the Italian ‘Almanaaco Republicano.’ It would later be translated by Riazanov and printed in Neue Zeit in 1914. This is its first English language publication.

‘On Political Indifference’ (1873) by Karl Marx from Workers Monthly. Vol. 5 No. 12. October, 1926.

[The following articles by Marx and Engels were originally written between 1872 and 1873. They were directed against the Italian Bakuninists who had charged the General Council of the Workingmen’s International at London with carrying on a campaign of calumny and deception for the purpose of forcing its “authoritarian and Communistic doctrine’ upon the whole International. The articles were published in the anti-Bakuninist “Almanaaco Republicano” for the year 1874, the literary supplement of “La Plebe” (The People), edited by Enrico Bignami since July 8, 1886. They were later reprinted in German with an introduction by D. Riazanov, at present director of the Marx-Engels institute at Moscow, in the Neue Zeit for 1913-14. Avrom Landy.]

THE working class must form no political party; under no pretext must it undertake political action, because to lead the struggle against the state would mean to recognize state and that is contradicting the eternal principles! The workers must conduct no strikes, for to conduct a struggle in order to force an increase in wages or to Oppose a decrease would mean to recognize the system of wage-labor and that is in contradiction to the eternal principles of the emancipation of the working class!

When, in their political struggle against the bourgeois state, the workers unite in order to obtain concessions, then they are concluding a compromise and that is contradicting the eternal principles! Hence, every political movement, such as the English and American workers have the bad habit of undertaking, must be condemned. The workers should not squander their powers in order to achieve a legal limitation of the working day, for that would mean to conclude a compromise with the entrepreneurs who in some cases would be able to skin the workers only ten or twelve hours instead of fourteen and sixteen. Similarly, they must not try to achieve the legal prohibition of factory work for girls under ten years of age, for by this means, the exploitation of boys under ten years of age is not yet done away with. Again, it would mean to conclude a hew compromise and that would have tainted the purity of the eternal principles!

Still less must the workers demand that, as is the case in the United States, the state, whose budget rests upon the exploitation of the working class, be obliged to grant the workers’ children elementary education; for elementary education is not yet universal education. It is better that the men and women workers be unable to read, write and figure than that they receive their instruction from a teacher in the state school. It is far better that ignorance and sixteen hours of daily labor render the working class stupid than that the eternal principles be broken.

When the political struggle of the working class assumes a revolutionary form, when in place of the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie they set up their own revolutionary dictatorship, than they commit the frightful crime of insulting the principles; for by satisfying their lamentable, profane daily needs, by breaking the resistance of the bourgeoisie, they give to the state a revolutionary and transitory form instead of laying down their arms and abolishing the state. The workers must organize no trade unions for that would mean to perpetuate the social division of labor as it exists in bourgeois society. For after all, this division of labor which divides the workers is really the basis of their slavery.

In a word, the workers should fold their arms and not squander their time on political and economic movements. All these movements can bring them nothing more than immediate results. As really religious people, scorning their daily needs, they must cry, full of faith: “Crucified be our class, may our race perish, if only the eternal principles remain untainted!” Like pious Christians, they must believe the words of the priests, scorn the blessings of this earth and only think of winning paradise. Read, instead of paradise, social liquidation which some fine day is to be effected in some corner of the world—nobody knows how and by whom it will be effected—and the deception is all the same. (1)

In expectation of this famous social liquidation, the working class, like a well-bred flock of sheep, must conduct itself respectably, leave the government in peace, fear the police, respect the laws, and offer itself without complaint as cannon-fodder.

In their daily life, the workers must remain the most obedient servants of the state; internally, however, they must protest most energetically against its existence and manifest their profound theoretical contempt for it by buying and reading pamphlets on the abolition of the state; they must beware of offering any other resistance to the capitalistic order than declamations on the society of the future in which this hated order will disappear.

No one will deny that, had the apostles of political abstinence expressed themselves so clearly, the working class would have sent them to the devil at once and would only have taken it as an insult on the part of a few doctrinaire bourgeois and ruined Junkers who are so stupid or so clever as to deny them every real means of struggle because all these means of struggle must be seized in present-day society and because the fatal conditions of this struggle have the misfortune of not conforming to the idealistic phantasies which our doctors of social science have set forth as goddesses under the name of Freedom, Autonomy, Anarchy. However, the movement of the working class is now so strong that these philanthropic sectarians have not the courage to repeat the same great truths concerning the economic struggle that they incessantly proclaim in the political sphere. They are too cowardly to also apply these truths to strikes, coalitions, trade unions, to the laws on woman and child labor, on the regulation of the working day, etc.

Now let us see to what extent they can appeal to old traditions, to shame, to honesty, to eternal principles.

The first socialists (Fourier, Owen, St. Simon, etc.) saw themselves compelled—since social relations were not yet sufficiently developed to make the constituting of the working class as a political party possible—to confine themselves to the portrayal of the model society of the future and hence to condemn all attempts such as strikes, coalitions, political action undertaken by workers in order to somewhat improve their condition. But if we have no right to disown these patriarchs of socialism, just as little as the modern chemists to disown their ancestors, the alchemists, we must still beware of falling back into the old mistakes; for, repeated by us now, they would be unpardonable.

In spite of that, much later—in the year 1839, when the political and economic struggle of the working class in England had already assumed a strongly marked character—Bray, a pupil of Owen and one of those who had discovered Mutualism long before Proudhon, published a book: Labor’s Wrongs and Labor’s Remedy.

In a chapter on the ineffectiveness of all means of deliverance to be attained thru the present struggle, he offers a bitter criticism of all economic as well as of the political movements of the English working class. He condemns the political movement, the strike, the shortening of the working day, the regulation of the factory work of women and children, because all these, he believes, only chain the workers to the present condition of society and sharpen its contradictions even more instead of leading them out of it.

And now we come to the Oracle of our doctors of social science, to Proudhon. Altho the master expressed himself energetically against all economic movements (coalitions, strikes, etc.), which stood in contradiction to the emancipating theories of his Mutualism, he still furthered the political struggle of the working class thru his writings and his personal participation; and his pupils did not dare to come out openly against this movement. Already in the year 1847, when the great work of the master, the “Philosophy of Poverty” or “The Contradictions of Economics” appeared, I refuted all of his sophisms against the labor movement. But in the year 1864, after the Loi Olivier which, even if in a very limited measure, granted the French workers the right of coalition, Proudhon returns to the same theme in a work which was published a few days after his death— “The Political Capacity of the Working Class.”

The attacks of the master pleased the bourgeoisie so much that the “Times,” on the occasion of the great Tailors’ Strike in London in the year 1866, conferred upon Proudhon the honor of translating it and condemning the strikers with his own words. We here give a few examples:

The miners in Rive de Gier had gone out on strike and the soldiers hastened thither to knock reason into them.

“The authority which had the miners of Rive de Gier shot down, found itself in an unfortunate situation. But it acted like the old Brutus who, in the conflict between his emotions as father and his duty as consul, was obliged to sacrifice his children in order to save the republic. Brutus did not hesitate and posterity did not dare to condemn him on that account.”

No worker will recall a bourgeois ever hesitating to sacrifice his workers in order to save his interests. My, what Brutuses the bourgeois are!

“No, there is just as little right to coalition as there is a right to extortion, to swindling and theft, just as little as there is a right to incest or adultery.”

It must be said that there is certainly a right to stupidity.

But what are these eternal principles in whose name the master hurls his abracadabra-anathemas?

Eternal Principle No. 1: “The level of wages deter mines the price of commodities.” Even those who have not the slightest notion of political economy and do not know that the great bourgeois economist Ricardo, in his work: “Principles of Political Economy” which appeared in the year 1817, has once for all refuted this traditional, false doctrine, are still acquainted with the significant fact of English industry which is able to sell its commodities at a lower price than any other country despite the fact that wages in England are relatively higher than in any other country of Europe.

Eternal Principle No. 2: “The law that permits coalitions is entirely anti-juridical, anti-economical; it contradicts every society and every order.” In a word, “it contradicts the economic right of free competition.” Were the master less nationally limited, he would have asked himself how it could happen that even forty years ago a law had been promulgated in England which contradicts the economic right of free competition to just such an extent, why this law, to the extent that industry develops and together with it free competition “which so contradicts every society and every order,” forces itself upon all bourgeois states like an iron necessity. He perhaps would have discovered that this law (‘Droit” with a big D) is only to be found in economic text books written by ignorant brothers of bourgeois political economy, in the same textbooks which also contain pearls like the following: “Property is the fruit of labor…” of others, they forget to add.

Eternal Principle No. 3: “Thus, under the pretext of raising the working class out of its so-called degradation, they will begin with the wholesale denunciation of an entire class of citizens; the class of masters, of entrepreneurs, of factory owners and citizens. They will call upon the democracy of the handworkers to scorn and hate those fearful and unseizable conspirators of the middle class. They will prefer the struggle in trade and industry to legal pressure, the class struggle to the state police.”

In order to keep the working class from emerging from its social degradation, the master condemns coalitions which the working class, as a hostile class, opposes to the respectable category of factory owners, entrepreneurs, bourgeois who, like Proudhon, certainly prefer the state police to the class conflict. In order to free this respectable class from every inconvenience, the good Proudhon recommends to the workers, until their entrance into mutualistic society, freedom or competition which despite their great inconvenience still form “our sole guarantee.”

The master preached indifference in the economic sphere in order to secure freedom or competition, our sole guarantee; the pupils preach indifference in the political sphere in order to secure bourgeois freedom, their sole guarantee. If the first Christians, who also preached political indifference, used the strong arm of an emperor in order to transform themselves from op pressed into oppressors, the modern apostles of political indifference do not at all believe that their eternal principles enjoin them to abstain from worldly pleasures and fleeting privileges of bourgeois society. However that may be, we must say that they bear with a stoicism worthy of the Christian martyrs the fourteen or sixteen hours of work which weigh upon the factory workers.

NOTE

1. Marx is here referring to a resolution passed at the Rimini Conference (Aug. 1872) where the Italian Federation of the International Workingmen’s Association was constituted. It must be remembered that this was the period of the Marx-Bakunin struggle in the International and that Italy was a Bakunin stronghold. In this resolution, the Conference “proudly declared before all the workers of the world” that it “does away with all solidarity between itself and the London General Council which has used the most unworthy means of calumny and deception for the sole purpose of forcing its special authoritarian-communistic doctrine.” (According to Riazanov.)—A.L.

The Workers Monthly began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Party publication. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and the Communist Party began publishing The Communist as its theoretical magazine. Editors included Earl Browder and Max Bedacht as the magazine continued the Liberator’s use of graphics and art.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/wm/1926/v5n12-oct-1926-1B-FT-80-WM.pdf