For all of us ‘living’ with unaffordable rents in hostile cities designed exclusively for tiny parasitic minorities, this article may bring a tear to your eye. A look at the work of the recently renamed Leningrad from its Director of the Municipal Administration to redress decades of neglect providing housing and public services, transforming it to a city of and for the proletariat. Written at the height of the NEP years when private business in the city was flourishing, the priority remained the working class.

‘The Municipal Policy of the Leningrad Soviet’ by N. Ivanov from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 6 No. 3. January 14, 1926.

The municipal administration of S. Petersburg in pre-war times were in the hands of a census municipal authority: It served the interests of the bourgeoisie, of houseowners in the first place. Not only were the interests of the workers in the suburbs entirely ignored, but even in questions of public institutions in central parts of the town, everything was subordinated to the interests of houseowners. The streets in the town were covered with a variegated network of various kinds of pavement, because every houseowner paved the street in front of his own house, just as he fancied.

The situation was still worse with regard to the drainage The rotting wooden sewage pipes with the outfall of the wastewater directly into the rivers and canals within the precincts of the city; defied the most modest demands of hygiene. It was a question of life and death for the population of the city that they should be replaced. Because the costs of re-drainage would have fallen on the houseowners, the town administration constantly postponed the solution of this question for 60 years, leaving the inhabitants to suffocate in filth. The St. Petersburg of the pre-war times was a picture of the whole bourgeois world; externally beautiful — but, on closer acquaintance chaotic, uneconomic, rotten to the core.

The welfare and outward beauty of the central parts of the town inhabited by the bourgeoisie — this was the task of the municipal administration. The suburbs inhabited by the workers lacked the most primitive measures of public care, they were piles of close, gloomy and stinking houses. In order to carry out with more ease the policy of the neglect of the working-class districts, the limits of the town were artificially kept always in the same place. The town grew and new suburbs were joined on to the built-on area, but they remained outside city precincts and the care of the municipality. Thus for instance, the gigantic area of Wolodarski (the town is divided into six districts), which is thickly populated with workers, remained for decades outside the city limits and for this reason the laying on of a water supply was refused to it. The inhabitants were obliged to make use of the uncleansed water of the Neva, which spread infection. It is only under the Soviet Power that the inhabitants of this district have at last got a water supply.

The first step of the Leningrad Soviet was the extension of the borders of the town. More than half the urban territory was formerly excluded from the administration. It is clear that the neglected part was the half which was inhabited by the proletariat.

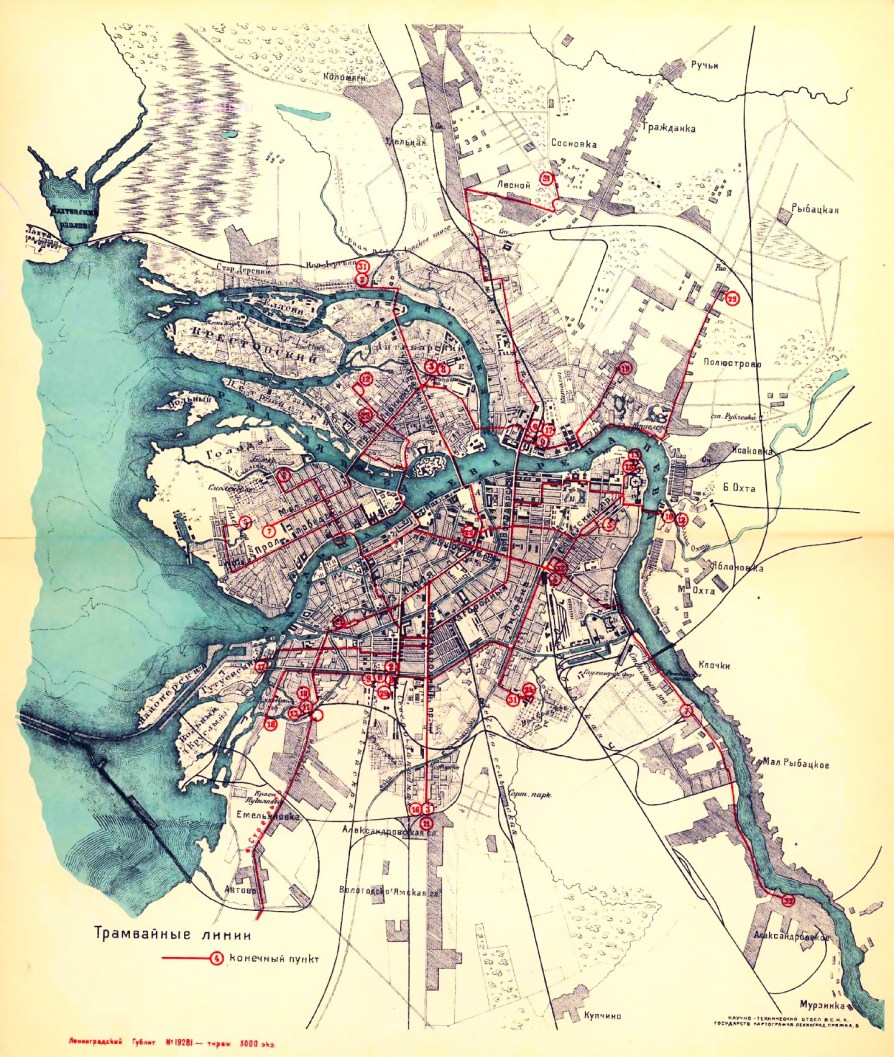

The Leningrad Soviet is now devoting the whole of its attention to these working-class districts. Its chief work is being done in the parts which were forgotten by the bourgeoisie. These districts have now got 19 km. of water mains. The water supply provides 70,000 persons of the working-class population with water. The municipal tramways are paying more and more attention to satisfying the needs of these districts. In the last three years, a number of main tramway lines have been laid in the working-class areas.

This endeavour to serve the working-class districts in the first place, is also evident in all other fields of municipal work. Thus for instance, 67,8% of the repairs to pavements are in working class areas. The same is seen with regard to drainage.

In 1925, 69,1% of the whole repairs were carried out in working-class districts. The new cement drain-pipes were constructed chiefly in the proletarian parts of the town. The Leningrad Soviet took up with determination the work which the bourgeoisie had postponed for 60 years. Even in the years of the most terrible fight against the consequences of destruction, it found the means to lay 41 km. of mew cement drain-pipes, thus laying a firm foundation for the solution of the sewage question. In the working-class districts, street planning is being re-arranged, new broad streets are being made, bordered with grass and new gardens and parks being laid out. By far the greater part of all the gardens and parks of the old St. Petersburg were in the central parts of the town. There were almost no gardens for public use in the working-class districts, although in these quarters there were two gigantic parks with an area of more than 50,000 sq. km. which however, were surrounded by high walls and were only at the disposal of their owners. The Leningrad Soviet has opened the gates of these parks to the workers. It has extended the parks, carried out the necessary works and turned them into a favourite resort of the proletariat. The Soviet has proceeded in this way in all working-class quarters, has opened a number of private gardens for general use and laid out many new parks. In place of the waste ground and dumps which swarmed with workers’ children, new gardens and playgrounds have arisen.

In the fast three years, 16 gardens and a number of children’s playgrounds, covering an area of 47,000 sq.km. have been newly laid out in the working-class districts.

The fact that this task could be so rapidly accomplished is due to one of the fundamental achievements of the proletarian revolution in the town, i.e. the municipalisation of land and of buildings in the towns. We have already pointed out that private gardens were handed over for public use. The opening of new parks in the place of waste ground would also have been impossible if the land had remained in the hands of private persons.

It is not however in the question of gardens alone that the tremendous importance of the municipalisation of the land becomes evident. All questions of rational re-planning of towns are closely bound up with it. Leningrad is growing, the needs of industry and of the urban population are increasing and, in connection with this, it has become urgently necessary to re-plan a number of streets and open places in the town.

But, great as is the significance of the municipalisation of the land and buildings for rational planning and the development of public welfare, this is not its chief significance. Formerly, when houses were in the hands of private owners, and the municipality, which consisted of houseowners, did not dream of controlling their appetites, the housing question was the most difficult one for the working population. Rents were determined entirely by the wishes of houseowners.

The worker, who was badly housed, paid on an average 19% of his wages in rent.

The proletarian revolution seized all houses from the hands of houseowners and handed them over to the Soviet.

The administration of the houses is in the hands of the tenants themselves. The occupants of every house form a housing co-operative and elect the persons who shall manage the house. All those who have the franchise according to the Soviet constitution can take part in these elections. Workers and employees are in the majority in the house management committees. The number of workers at present in the house management committees of Leningrad is 59,7%, of employees 32,7%, disabled persons and unemployed 3,4%; only about 4,2% are from other strata of the population.

The workers have proved that they administer the houses no worse than the houseowners. All damage suffered by the houses during the war and the blockade are being repaired. The tenants look after their dwellings themselves and have long forgotten the former dreaded houseowner who postponed the necessary repairs for years.

Premises used for trade and industry remain in the hands of the Soviet, and the rent is used for the welfare work of the town, partly for purposes of education and public health.

The rent is fixed by law and no one has the right to raise it. The amount of rent is fixed according to the occupation; for workers and employees in proportion to their wages. Merchants and other citizens who do not live on their earned income, pay as a rule ten times as much as a worker. Workers with wages paid up to the fifth grade pay altogether 10% of the pre-war rent. The highest rent paid by workers with top wages amounts to 20% of the pre-war rent. The unemployed pay according to the lowest tariff Workers and employees do not pay the rent in advance, but ten days after they have completed a month in the house.

The whole income from the house is used for its benefit and maintenance and the tenants themselves dispose of it. It is only in houses where a large non-proletarian element lives that a special rent is now collected. This is used for the construction of new houses in working-class districts, and new buildings are urgently needed. Regardless of all measures which are taken to make it easy for the workers to move into the central parts of the town, they prefer to live near the factories so as not to waste time on the journey to and fro. This question is affected to no small degree by the fact that in the majority of cases the undertaking in which the workman is employed, attaches him to itself by the broad development of social life. The old dwellings however are on the scale of the pre-revolutionary standard of living of the workers and cannot satisfy their present demands. For the purpose of increasing the housing accommodation general repair of damaged buildings was carried out. In 1924, 135 houses were repaired by the municipality.

This however was not enough and the Lemingrad Soviet proceeded to build new workers’ houses. The plans for these were elaborated by competition in which the best architects took part. As the result a number of new blocks of houses were erected. The flats in the workmen’s dwellings are comfortable. In the new quarters, so-called “homes of culture” are built at the same time for meetings, entertainments etc., and schools for the children.

In the domain of municipal undertakings, the Leningrad Soviet observes the same policy as in the other branches, that of making them as far as possible accessible to the working population and of satisfying their needs in the first place. We have already pointed out that the workers’ quarters are first taken into consideration in the extension of the network of tramways and the drainage system. In the exploitation of these undertakings also, the same principle is observed. A special tariff for workers and employees has been introduced on the electric tramways. The trade unions issue 5 million tickets for 35% reduction every month. Further, the tariff zones are longer in the workers’ districts than in the centre, 5km. as against 3 km. In order to facilitate the workers visiting theatres, museums etc. situated in the centre of the town, there are reduced return fares to the centre. In this way, the tramways have become a means of transport for the workers. Before the war, there was an average of 149 tram journeys per head of the population annually, in 1925, 224.

All measures of municipal administration are submitted to a detailed examination by the municipal section of the Leningrad Soviet. In this section, 263 members of the Soviet are at present working, of whom 49% are workers and 51% employees. Apart from the plenary meeting, the section has a member of subcommittees for the individual branches of municipal administration. The municipal administration is always kept in daily touch with the workers of Leningrad through the members of the Soviet.

The proletarian class point of view is the basis of the whole communal policy of the Leningrad Soviet. The communal Soviet administration places the requirements of the working population in the centre point of its work. To improve the living conditions of the worker, to give him joyous recreation after his work in the service of the community, to turn the town from a pile of mass dwellings into a healthy, light and beloved place of residence for all workers — these are the chief tasks of the municipal Soviet administration. A new life is being created for us with an easy grace through the initiative and energy of the workers.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly.

PDF of full policy: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1926/v06n03-jan-14-1926-Inprecor.pdf