Sam Darcy, the California District Organizer for the Communist Party, wrote this major evaluation of the San Francisco General Strike of 1934 for the Party’s theoretical journal. Perhaps the most important class battle with Communist leadership in U.S. history, the strike was part of a wave of confrontations involving millions of workers that watershed year.

‘The San Francisco Bay Area General Strike’ by Sam Darcy from The Communist. Vol. 13 No. 10. October, 1934.

WE ARE discussing the largest single strike in the history of the country. We are discussing also, the first general strike in which it could be said that our Party participated as a Party. For both these reasons it is important to examine certain basic questions concerning general strikes.

What is a general strike? Some commentators on the San Francisco General Strike have written that in San Francisco we did not have a complete general strike, in that there was not a complete cessation of all activity, including food, electric light and power, water supply, etc.

OBJECT OF GENERAL STRIKES

The character and form of a movement are necessarily determined by its objectives. The object of the San Francisco General Strike, or, for that matter, any conceivable general strike, should be, not to inflict hardships on the poorer sections of the population, but to stop profits. But, because of the circumstances under which our general strike took place, it could not stop profits entirely. We very carefully organized the strike so as not to cause any suffering to the general masses of the people. It stands to reason that in a revolutionary situation the general strike would necessarily have a deeper function. It would have the object of seizing the industries and eliminating all capitalist control.

In a situation such as we had in San Francisco, the fact that the water supply, electric light and such other utilities did not join the general strike was not a hindrance to the general mass character of the strike, although it was a tremendous weakness. Had the strike been under revolutionary leadership and the workers in these industries properly organized, these utilities would have been regulated and subordinated to the interests of the general strike, so as to serve exclusively the needs of the workers and allied sections of the population.

INCOMPLETENESS OF SAN FRANCISCO GENERAL STRIKE

The San Francisco General Strike was incomplete, due to two main factors. The first factor was the failure of the workers to stop the bourgeois newspapers from publishing. The failure of the printing trades to join the strike was due, on the one hand, to the weakness of the revolutionary groups within these trades, and together with that, to the more backward political condition of these workers, due to their psychology as highly skilled workers enjoying a relatively higher standard of living.

The second factor was the failure of the workers in the communication systems, such as telephone and telegraph, to join the strike. This was due to the refusal of the A. F. of L. bureaucrats to call a strike and to our neglect and inability prior to the period of the actual strike, to organize the workers in the communications industries, and to the success of the fakers in outmaneuvering us among those sections of the communications industries where the workers were organized. We were of little account in these industries, having but a few contacts in the telephone, telegraph, and electric light and power companies, and nothing in the radio communications. Had we succeeded in bringing these communication workers out on strike, and keeping the communication system operating only to the extent that it would have helped the strike, the entire struggle would have reached a higher political level, because the question of the ability of the capitalist State to function would have been far more critical for the bourgeoisie than it was.

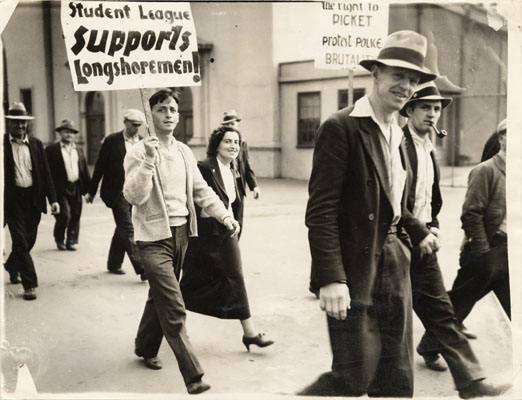

Many bourgeois writers have consoled themselves with the thought that this strike had only purely economic or trade union organization objectives. The Nation even arrived at the remarkable conclusion that there “never was a general strike,” and that “the Communist Party walked in at the last moment to be the scapegoat”. As one of the evidences, we are told that all the workers struck, not on behalf of themselves, but only “in sympathy” with the marine workers! Practically all bourgeois writers have thus concluded that the San Francisco General Strike could not in any sense be considered a political strike. Let me state here that there would have been no maritime or general strike except for the work of our Party. The statement issued jointly by the Central and the California District Committees clearly stated that neither the Communist Party nor the working class entertained any idea that the strike had the objective of seizing political power, although the State terror against the strikers, the clearly revealed function of the Government apparatus as executive committee of the exploiting class, was bound to arouse the workers involved in bitter conflict to the consciousness of the real nature of the bourgeois-democratic State. The very fact that it was a sympathy strike gives it its political character, because it was, first, a declaration of class consciousness on the part of the San Francisco workers, and, secondly, an act of united class action.

OBJECTIVES OF SAN FRANCISCO GENERAL STRIKE

The objectives of the General Strike can be said to have been three-fold.

1. For several years a movement of growing militancy was evident in California, and particularly in San Francisco, which affected every section of the working class. This growing militancy was led by Communist Party members or close sympathizers. The original strike in the marine industry began against an effort of the capitalist class, with the shipowners at their head, for a counter-offensive against this growing working class militancy. Its concrete form was their effort to break the job control which the militant International Longshoremen’s Association local was gaining. It was for this reason that the main issue was the hiring-hall control.

The first objective of the General Strike was to defeat this counter-offensive. The fight began in the decisive sector of San Francisco’s economy, namely, the marine industry, and upon its outcome largely depended the future ability of militants to lead trade unions in any industry in that area.

2. The second objective, inter-dependent with the first, was to force some economic concessions from the capitalists. The workers in all industries were aware that upon the outcome of the fight with the shipowners depended their ability to gain concessions in their own industries.

These two objectives were conscious, stated, objectives of all the workers, and even of many of the bureaucrats during the period of the strike.

3. There was a third objective, not so clearly stated (except by the Communists), but nevertheless clear to all the workers, and that was to compel the Government to withdraw all the forces it had put into the field on the side of the shipowners and against the workers. These included, in the first place, the Federal Government Longshoremen’s Board; in the second place, the municipal police; and in the third, the State National Guard.

All the workers were fully conscious of the objectives of the strike against the military forces. But not all the workers were fully conscious of the objective of the strike against President Roosevelt’s agents, the National Longshoremen’s Board. However, the maritime workers and large sections of the workers in other industries, including large and decisive local unions, such as the teamsters, which took official action through resolutions, motions, speeches, etc., showed that they understood that the Federal Board was no less a tool of the shipowners to break the strike than the armed forces,

POLITICAL CHARACTER OF STRIKE

It is apparent from the stated facts that in every way objectively, and for large numbers of workers consciously, the strike had a definite political character. In fact, even before the actual strike began, the struggle for the political aspects of the strike had become the dominant issue.

While, as stated before, the strike was not a revolution, we had a distinct and clear glimpse of how the struggle for power develops under the peculiar circumstances that obtain in the United States. These aspects of our discussion are, of course, the most significant. But before we come to them, let us first review the strategy and tactics of the development of the strike itself.

In the article which I wrote for the July issue of The Communist, I recounted the main facts, from the beginning of the movement for struggle in the maritime industry, until the second week of June, which marked the beginning of the transition from the Maritime to the General Strike. I shall therefore not repeat at any length the facts already related.

BEGINNINGS OF GENERAL STRIKE MOVEMENT

It will be remembered that on June 16, Ryan, together with a small clique of local officials from the West Coast, made his now notorious agreement with the shipowners. The workers rejected this agreement unanimously on June 17. On that very day it was obvious that all the capitalist forces were being mobilized in support of this agreement. The press carried pictures and headlines that the strike was over. Several hundred new police were sworn in to help carry it through. Ryan and the shipowners were obviously preparing to force a return to work on Monday, June 18, and for a clean-up of the militants in the union.

Some counter-step had to be taken. The Joint Maritime Strike Committee, therefore, called, two days later, for a great mass meeting of all striking workers and other trade unionists.

About a week previous, in anticipation of the possible need for a general strike, we had succeeded in convincing the Painters Local 1158 to sign a circular letter addressed to all other locals of the A. F. of L., declaring their own support for a general strike, and asking their vote for it, so that, should such a general strike become necessary, it would be possible to call it at the critical moment without any harmful delay.

Only two or three locals had acted on the painters’ circular letter by June 17, when the longshoremen rejected the Ryan agreement. When we called our mass meeting, therefore, for June 19, we decided to make that the test as to whether a general strike was realizable or not. That that meeting was critical for the entire situation became clear immediately. Mayor Rossi himself asked to appear before the meeting to speak against any further effort or action by the workers, and for arbitration and the acceptance of the Ryan agreement. Ryan himself asked to speak. We could not avoid allowing Rossi to speak, the object of that being to relieve the pressure on the militant leaders of the strike, who were being accused: of carrying their militancy beyond the wishes of the masses of the workers, and to demonstrate to everyone that the workers themselves were militantly opposed to Rossi, Ryan, and their policies. We have already reported in the article in the July issue of The Communist how Rossi was booed down, how the very mention of Ryan and the A. F. of L. was hissed, and how a tremendous ovation, lasting several minutes, greeted the call for a general strike.

After that, the general strike movement developed rapidly. The very next day the Machinists Local 68, the oldest, and very influential A. F. of L. local in San Francisco, had the largest meeting it had held in 14 years, and voted to join the general strike movement. Hoping to stem the movement, Roosevelt announced on the 20th, that he had put through the Wagner Labor Disputes Bill, which was then ballyhooed by the A. F. of L. fakers in San Francisco in an effort to stop the locals from voting for a general strike.

THE GENERAL STRIKE CAMPAIGN

Of course, the general strike movement was in no sense a spontaneous movement. It took long and careful preparation. At first the militants sent small committees, chiefly from the longshoremen’s local, to other A. F. of L. locals, appealing for support by a vote for a general strike. First we tackled only those locals that we knew were most militant. As we began to tackle the larger locals and those in the key industries which would be critical for the outcome of the general strike, we sent, not small delegations, but delegations ranging from 50 to as much as 400. It was only because of this form of organization of the campaign for the general strike that we were able to create a great initiative of the workers themselves to organize the strike and did not depend only on our older experienced forces, that we finally succeeded in giving the strike movement the broad character which it ultimately developed.

While all this was going on the Communist fraction in the Central Trades Council was making motions to consider the general strike, but because of its numerical weakness, was continually ruled out of order. It thus appeared outwardly, and in the capitalist press, that the General Strike movement was, every Friday night, when the Central Labor Council met, given another setback. But at the very same time, the General Strike movement was actually advancing very rapidly, by the votes which were daily taking place in the local unions stimulated largely by the delegations of militants.

At this point, it might be pertinent to consider why the General Strike movement had not even gained any serious headway in Los Angeles, for example, whose harbor at San Pedro was also on strike. There we issued similar agitation for a general strike as we did in San Francisco, but there was lacking a carefully and skillfully planned organizational character to develop the movement for a strike. When the San Francisco movement for a general strike was beginning to reach a head, and our Los Angeles comrades realized that there they had very few locals mobilized for supporting the general strike, they tried to overcome this shortcoming by sending a delegation into the Central Labor Council to demand a general strike. This was obviously only abstract agitation because no base had been prepared for such action. To make matters worse, the delegation consisted of unemployed organizations and the Marine Workers Industrial Union. Obviously, this gave the Central Labor Council fakers the opportunity they wanted to rule the whole question out.

In the agricultural fields we had a similar situation. Because of the popularity of the revolutionary movement amongst the agricultural workers, it was expected that we would be able to get them to join the general strike movement. However, we had done nothing of an organizational character to realize this, so that the leaflets and statements issued by some of the comrades to the newspapers made us appear ridiculous when the time came for producing the threatened action.

In considering these weaknesses of the preparation period of the strike, we must also cite the big gap between the theory and the practice of the fractions in the T.U.U.L. unions. The Marine Workers Industrial Union, for example, has as one of its best features, its industrial character. Yet the workers in the Longshoremens local, an A. F. of L. affiliate and a craft union, were able under the pressure of circumstances, quickly to break down their own routine work inside their own local, and reach out to other locals as far removed from longshore work as bakers and cleaners and dyers, and help organize them for the general strike. But the Marine Workers Industrial Union was so much under the influence of craft ideology, that during the entire period of the preparation of the general strike, it sent not a single delegation to even the independent unions and the few T.U.U.L. organizations, such as the fishermen. For this of course, the fractions are generally responsible.

The period of June 19, when the mass meeting took place, to July 6, was a period of intense mobilization, by both sides, of all forces possible, for what was clearly becoming a general conflict. During this period the Central Labor Council continued to rule the motions for consideration of a general strike out of order. Our strategy, in the interests of the strikers, was to use the Joint Maritime Strike Committee as a base. This committee had 50 members, and as fast as any other A. F. of L. local voted for the general strike they were also asked to elect two members to be added to the Joint Maritime Strike Committee, which, in this way, we hoped to transform into a general strike committee. This movement went quite well until July 6.

BLOODY THURSDAY AND AFTER

In fact, the last few days before July 6, the movement received a tremendous acceleration by the following incidents:

On July 3, the shipowners attempted to open up the port of Portland and failed. On the same day the workers on the State Belt Line in San Francisco, a small railroad which until then had been scabbing, quit their jobs under pressure from the waterfront pickets. ‘The State Government made an effort to operate the State Belt Line, both through trying to terrorize the workers back to work, and through the use of scabs; but they failed.

On July 5 the National Guard took control of the waterfront. It was on that day that the great assault on the workers took place, which has since become known as the Battle of Rincon Hill on Bloody Thursday. The battle continued for all of the next day, July 6, when Sperry and Counderaikis were murdered. On that day finally, the Joint Maritime Strike Committee issued a leaflet openly calling for the General Strike.

On the evening of July 6 it became evident that the Central Labor Council fakers knew they could not simply ignore the General Strike movement, so they decided to take over its leadership and strangle it. They elected a Strategy Committee of Seven, which committee announced as its function, the attempt to get the best conditions possible for the maritime workers, and to look into the question of a general strike. The preponderant part of the San Francisco workers took this to mean that the Central Labor Council was yielding and was taking measures really to organize the General Strike. How strong the illusions concerning this committee were, was evident the very next day, when the General Strike Committee (with the Joint Maritime Strike Committee and the two from every local) was to meet. Our fraction had clear instructions on that day to do everything possible to bring about a rank-and-file strike committee to proceed with the calling of the strike. Instead, our own leading comrades in the leadership of this conference, in deference to the wishes of this Strategy Committee of Seven, decided not to take final action on that day until the Strategy Committee had the chance to do something. Obviously, our comrades would never have acted that way were it not for the fact that they did not understand that the Strategy Committee had been appointed to kill the strike, and not to organize it.

Events developed very rapidly. Under pressure from the rank-and-file teamsters, Mike Casey, a faker of the type of Ryan, was forced to call a membership meeting for July 8 to consider the question of the walkout. At the July 8 meeting, he could not succeed in preventing the vote for the strike, but on July 8, after the strike vote was taken, he succeeded in passing a motion that the actual strike should not take place until the following Thursday, July 12, and that no other meeting be held on Wednesday night, prior to the actual walkout, to judge whether, in the meantime, the situation had not changed so that the question of strike should be reconsidered. Getting the teamsters to join the strike was at this time the main force needed to make certain the eventuality of the general strike. This was due to the prestige and strategic post which the teamsters had.

On July 8, the funeral of Sperry and Counderaikis took place, the size and impressiveness of which have since been made well known. This also helped give the workers the necessary confidence to join the general strike movement.

On July 10 the Alameda Central Labor Council, which is on the opposite side of the bay from San Francisco, and is related to San Francisco as St. Paul to Minneapolis, or Brooklyn to Manhattan, under the influence of a strong A. F. of L. opposition group that we had there, called for a strike vote.

THE ATTEMPTS TO STEM THE TIDE

On the 10th the National Longshoremen’s Board went into action in a last desperate attempt to stop the strike movement. However, the speeches of the strike leaders who testified there were carefully prepared and were continually aimed at exposing arbitration, thus providing additional stimulus to the General Strike movement. Harry Bridges, the accepted leader of the longshoremen; Harry Jackson, the head of the Marine Workers Industrial Union; and other militants spoke. The shipowners came with very conciliatory phrases in an effort to stop the general strike movement.

Up to this point they had refused to meet with seamen, claiming that the shipowners had no organization that could effectively negotiate with seamen, and further, that the seamen would have to deal with individual shipowners who had been jointly operating a Fink Hall in San Francisco for a good many years.

However, on the 11th, the testimony of Plant, the most outspokenly reactionary leader of the shipowners, agreed to meet with the seamen for “collective bargaining”. One of the demands of the maritime workers was, not only collective bargaining, but an acceptance by the shipowners, of a “united interest” between seamen and longshoremen. This point Plant evaded.

While these hearings and maneuvers were going on, the militants intensified their drive to visit locals and convince them to join the general strike. On the night of the 11th the teamsters met. This was, in a sense, a point which was decisive for the general strike. The capitalist class was aware of that. Archbishop Hanna publicly prayed that the teamsters, who were largely Catholics, would vote against the strike. The I.S.U. leader, Furuseth, had pictures of himself in the newspapers, weeping at any continued conflict. A delegation of the Strategy Committee (which had by now become thoroughly discredited, all the workers having taken up the Communist name for it of “Tragedy Committee”), appeared before the teamsters and were howled down. The teamsters demanded to hear Bridges, who was given a tremendous ovation, and they finally voted to go out the next morning.

THE BALANCE SHEET ON THE EVE OF THE STRIKE

By the next morning, July 12, 60 local unions had voted for the general strike and about 10 locals were already out. We had pulled out these locals in sympathy, and as a measure of insurance, Contra Costa Central Labor Council (which adjoined Alameda) submitted the question to a vote of its locals. ‘The newspapers printed daily stories of how the British General Strike, the Seattle General Strike, and other similar movements were broken. On the evening of July 13, at the Central Labor Council meeting, it was evident that the General Strike movement could no longer be stopped, and so they decided to become its leaders and defeat it.

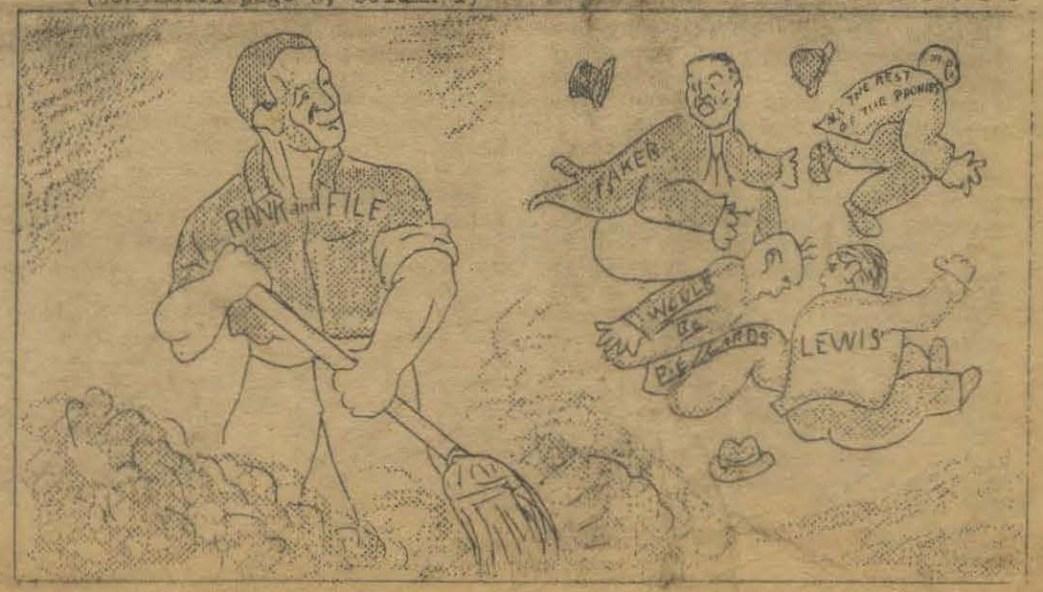

Here, again, was manifest our weakness in fighting against the A. F. of L. fakers. It was our failure at this point, to prevent the fakers from taking over the leadership of the strike, that cost us the eventual loss of the strike. The fakers dropped the discredited Strategy Committee of Seven, and called upon every local union to select delegates to a General Strike Committee, which was to meet the very next morning at 10 o’clock. Obviously, the fakers did this with the objective of preventing any democratic elections in the local unions. Instead, they ordered the officials to select the delegations of five from every local. ‘Thus, on Saturday morning we were faced with a general strike committee of about 800 members, the majority of whom were paid officials, appointed by the other paid officials. Had we succeeded in preventing this maneuver of the Central Labor Council fakers the outcome of the General Strike would have been very much different. But we were paying for our neglect of A. F. of L. work for ten years previous, and we found at the July 13 Central Labor Council meeting, that we could really count on only 60 reliable militant delegates being appointed to the General Strike Committee. The next morning, under the general impetus of the movement, we found many times 60 supporting us, but even so, the numbers that we had were outweighed by the paid officials, where reactionary fakers were in control.

Saturday and Sunday were used by the militants for two activities, first, to pull the remaining locals out, and, secondly, to mobilize for organizational contact. We had to develop a movement within all the local unions, for special membership meetings to elect the five to the General Strike Committee instead of appointing them. The militants also tried through agitation, such as a leaflet issued by the Longshoremen’s local, a statement issued by Harry Bridges, an appeal by the Party and the Western Worker, etc., to stimulate the workers to force the election of the delegations of five to the General Strike Committee in their locals. In this we were only partially successful.

By Sunday night, when we took stock of the entire situation, we came to the conclusion that we were not outnumbered amongst the rank and file insofar as sympathetic sentiment went, but that we were hopelessly weak in organizational contact to put the strike into militant hands. We realized, what should become one of the outstanding lessons to the whole Party, that we were not able in the last weeks of strike (for the first six weeks of the strike most of the other A. F. of L. opposition groups did not even meet), to overcome the years of neglect of our work in the American Federation of Labor.

This, plus the political errors that were made, especially in the failure to carry out determinedly the line of the Party to build a militant General Strike Committee led by the maritime workers, lost us the leadership during the period of transition from a maritime strike to the General Strike.

Although the strike was to begin the very next morning, the preparations for the effective conduct of the strike were obviously very poor. Not a single step had been taken to pull the unorganized workers out on strike. The General Strike Committee of 25, which was appointed by the fakers, made no effort to contact and put under general direction the sympathetic strike which began in Alameda County. The General Strike Committee leadership was determined to block every effort to spread the strike. When outside workers or union officials inquired as to what should be done, they were told to wait and see what happened.

In Portland, where a strong spontaneous movement for a general strike showed itself amongst the workers, our comrades were obviously unable to lead it into an actual general strike action. We tried at least to get an appeal from the San Francisco General Strike Committee to the Portland workers, hoping that that would stimulate the militancy among the workers so as to bring them out; but we failed to get such an appeal. From Seattle there was some talk and leaflets about a general strike, but there was very little sign of its declaration.

And the San Francisco General Strike Committee leadership was a solid blank wall against every effort to issue appeals to those workers to join the General Strike movement. ‘Thus, the best weapon for winning the strike, namely, spreading it, was blocked by the A. F. of L. fakers.

On Sunday afternoon, before the strike, the typographical union had a meeting for a final consideration of their strike action. They had not a single excuse for not going on strike, not even the stock-in-trade excuse of all fakers that they would jeopardize their agreements, because the typographical agreement had just expired. The sentiment for joining the General Strike was running fairly high when Howard, the president of the union, who had been in San Francisco the previous week, produced a trump card at the last minute, by informing the workers that the publishers had agreed to a 10 per cent raise in wages. He threatened the workers with all the other threats which fakers us” and finally succeeded by a vote of about three to one (with 400 voting) against joining the strike.

In our balance sheet on Sunday night we realized that this was one of the biggest blows we had received, because it was to prove a powerful weapon in the hands of the capitalist class against us.

THE HISTORIC STEP FORWARD

On Monday morning the General Strike was effective beyond all expectations. Not only had the overwhelming bulk of organized workers joined the strike, but many thousands of unorganized workers walked out and asked for organization. With the two exceptions already mentioned at the beginning of this report, namely, the printing trades and the communications, the city was very effectively tied up. Nothing moved in or out of the city. For practical utility, there are six ways of entrance to the city. These are: (1) Bay Shore highway; (2) U.S. 101 road; (3) Skyline Boulevard; (4) the ferries; (5) by sea; (6) the railroads. Every one of these ways, excepting the ferries and railroads, was patrolled by our picketing squads of workers. Nothing moved without permission of the strike committee. Within the city, transportation was tied up; production stood at a standstill. Workers, who had been afraid to admit being members of even A. F. of L. unions, were proudly wearing their union buttons all over the city. The whole capitalist class was stunned. They never believed that such a high degree of class consciousness had been reached by the workers. The San Francisco News said in its editorial, “The dignity of labor has taken on a new meaning today”. It was obvious that the military forces were helpless against such a strike movement.

BETRAYAL FROM WITHIN

Because of the dramatics involved in the great terror which developed against the workers on the West Coast, workers throughout the country are of the opinion that the strike was broken by terror. That is very far from the truth. After the strike was already broken by the A. F. of L. fakers, the terror then became effective as auxiliary strike-breaking machinery. Every act committed by the General Strike Committee leadership was an act to liquidate the strike, to kill it. ‘There was not even a bluff made by the Central Labor Council and General Strike leadership of using their leadership to win the General Strike. Three officials were elected by the paid bureaucrats, who packed the General Strike Committee. They symbolized the entire policy of the fakers. Vandeleur was chairman, and Vandeleur comes from the Municipal Carmen’s Union, whose members, despite all the threats that they would lose their contracts, seniority and civil service rights, defied their leaders and joined the strike. But one of the very first acts of the General Strike Committee was to order the Municipal Carmen back to work without any limitation, on the excuse that the general public needs transportation.

The secretary of the General Strike Committee was Kidwell of the Bakery Wagon Drivers, who succeeded in preventing his local from coming out on strike, by the convenient method of never even calling them to vote on the question.

The vice-chairman of the Strike Committee was Deal, who, in a similar manner to Kidwell, prevented his local union, the Ferry Boatmen, from coming out on strike, and provided one of the only two avenues of entrance to the city that the strikers could not control.

Thus, these three leaders of the strike were all officials of unions that were not striking.

We have already said that they occupied their energies with liquidating the strike. Here are some examples: They issued permission to scab truck drivers to bring their trucks into the city with various commodities. They authorized 70 restaurants to open and function. We have already reported how they ordered the Municipal Carmen back. Despite all these things, at the end of the first day, the strike was still solid.

On the morning of the second day there was a test motion put: that was on advising the maritime workers to accept arbitration. This was carried 207 to 180, with most of the members of the General Strike Committee absenting themselves or abstaining from voting. Even this vote was challenged by the militants because it was taken as a standing vote counted by the officials who refused a roll call count. But it is obvious that even in this packed General Strike Committee, in the face of the militancy of the rank and file, large numbers of bureaucrats were afraid to align themselves openly with the fakers. With over 400 paid officials, they could claim at most 207 votes.

That same day President Green issued a statement which was widely popularized throughout the city, saying that the strike was “unauthorized”, and that the National A. F. of L. opposed it. The only motion that the Communists and militants were able to carry through was a motion to enlarge the Executive Committee of the General Strike Committee from 25 to 75 and instead of having the additional 50 appointed as the previous 25 were, to have one elected from each of 50 of the largest local unions. All the rest of the activities of the A. F. of L. fakers were in line with the acts already mentioned, Vandeleur and company were in continual conference with Mayor Rossi and other representatives of the bosses. The subject of the conferences and decisions arrived at were never made public.

The tide of militancy rose every day that the strike continued, so that when, on Wednesday, the fakers finally felt they had to call off the strike before it got out of hand, they had to put through similarly a fake standing vote where they were clearly in the minority but where after refusing a roll call vote, they claimed a vote of 191 to 174.

THE POLICY OF THE MILITANTS

What was the line of the militants in the General Strike Committee and in the strike? We have already said that our object in the strike was to make the strike effective against the capitalist class and in every way to aid the masses. We worked out all our proposals in line with this general objective. At the very first meeting of the General Strike Committee the militants brought in proposals for the organization of committees: (a) to fight profiteering; (b) to insure housing and against evictions; (c) to insure food supply at no cost or at wholesale cost through an apparatus established by the strike itself; (d) for picketing and defense of the strike.

At the first meeting of the General Strike Committee either the labor fakers did not grasp the significance of these proposals, or they followed the tactic of letting them be accepted, and then killing them by failing to execute them. No matter what their reason was, they let these motions pass. The chairman of the Strike Committee even made a bluff at appointing some of these committees. However, the very next morning the newspapers carried eight-column streamers denouncing these proposals as an effort “to remove constituted authority and take the city over for the strikers”. Under the barrage of propaganda by these newspapers, the labor fakers effectively stifled most of these committees and prevented their functioning. Because of the tremendous upsurge from below, however, they were not able to stop the picketing, and because the city administration had practically no forces for effective scabbing, because they had only the military forces and thugs at their disposal—and among the military forces there were even some that were wavering in our favor— they were unable to utilize the paralyzing work of the General Strike Committee in order to break the strike. In the National Guard, 35 members, mostly musicians, refused to go on duty, when ordered. Also in the 250th Artillery Division, several arrests took place of guardsmen who were agitating against the orders. The bosses became almost hysterical when they found that the government with only the military was unable to re-establish the economic life of the city. For example, in Alameda County a meeting of ten mayors tried to organize a system of block committees for food supply. They never got to first base with this effort. In a widely popularized radio address by Governor Merriam that very day, he said: “By its very nature the general strike challenges the authority and ability of the government to maintain itself”. Had the General Strike Committee been in the hands of the militants it would undoubtedly have become the center of the city’s life.

As the matter stood, the General Strike Committee worked hand in glove with the capitalist class to bring about the defeat of the General Strike, as we have shown in the measures that they took.

TWIN SCREWS OF THE CAPITALIST SHIP OF STATE—BETRAYAL AND TERROR

On the third day of the strike, namely July 18, the ability of the fakers to call off the General Strike appeared to be in doubt. It was then that the terrific barrage of terror was turned against our Party, in an effort to decapitate the leadership of the strike. Our Party halls, and halls which even remotely had any connection with militant workers, were raided; individual comrades’ homes were wrecked and those found there arrested. Comrades were picked off the streets. An attempt was made to create a mass hysteria against the revolutionary movement and to destroy what the capitalist class calls the “center of direction”.

In this they failed, first, because, despite all its weaknesses, the Party had achieved that state of improved organization where the police and vigilantes were not able to find the “centers of direction”. And they were not able to create a mass basis for their terror, because the betrayal of the fakers was not sufficient to break the deep-rooted militancy of the masses, who refused to be diverted from their struggle against the capitalist class into entering any anti-Red campaign.

On the contrary, everywhere during this period of terror, the Party found greater cooperation than ever before. For example, although we made no appeal for funds, hundreds of dollars poured in from sympathizers for several days after the raids began. In the distribution and printing of leaflets, and in finding meeting places, workers who had really nothing to do with the Party came to our assistance. It is because the mass basis for the terror was not there, that a large measure of legal functioning has been restored to our Party in San Francisco.

THE STRUGGLE AGAINST THE TERROR

During this period we found that every one of our comrades, no matter how weak, who was in a shop or trade union, suddenly gained amazingly multiplied strength, influence, and prestige, while the comrades who were only in street units found their effectiveness even lessened as compared to the previous period. Those of our comrades who were in the front line trenches of the maritime and general strikes hardly suffered at all as a result of the terror, because they were, so to speak, “hidden” among the masses and, having the confidence and support of large numbers of workers, were able to work more effectively in carrying out the Party line. But the comrade who was used to working from the base of a local headquarters or street corner meetings, found his functioning very much lessened; and these comrades were the ones who made up 90 per cent of those whom the police succeeded in arresting.

DANGER OF SPONTANEITY

Up until the time when the leadership of the general strike movement was seized by the fakers the Party held in its grasp the main link to the situation, namely, the forward movement for the general strike. Our errors were not always clear to ourselves because of the intense concentration on the main point. For example, in balancing the score sheets after the strike, we find that throughout the period of the developing general strike movement there was a strong element of spontaneity everywhere. But now that the strike is over, we find that only where we were organized to take advantage of that spontaneity has any certain tangible lasting benefit come to the working class. In other words, although under the general sweep of the movement we were able to bring into line many locals and shops where we had no contact, now that the strike is over, in many cases we do not even know the state of mind of the workers in those shops or locals. The danger of relying on spontaneity is therefore clearly evident, and probably the biggest shortcoming of the struggle was that our Party, due to poor day-to-day work previously, had such limited organizational roots amongst the masses, and that we had to rely too much upon the spontaneous response of masses to our agitation.

This lack of organization became particularly a sore spot with the T.U.U.L. and independent unions. The District Committee of the Party was so absorbed with the struggle in the A. F. of L. that it made the serious mistake of neglecting the work of the fractions in the T.U.U.L. It wasn’t until the very eve of the General Strike that the T.U.U.L. finally made an effort to hold a conference of T.U.U.L. and independent unions to establish a strike center for those unions which were not included in the General Strike Committee organized under A. F. of L. auspices. We had a wonderful opportunity to establish a great base for the proposed Independent Federation of Labor. There were unions such as the welders, the electric light and power workers, and many lesser trade union organizations, which are not in the A. F. of L. and which we, with a little effort, could have undoubtedly organized into an independent trade union center under the leadership of the present forces in the T.U.U.L. We did hold a first meeting of such a body but before we could get under way the strike was called off.

SHOULD THE STRIKE HAVE BEEN CALLED?

After the strike was over there was some opinion along the line, that since the Party and militants were aware of their weakness as against the A. F. of L. bureaucrats, and since we knew that the A. F. of L. bureaucrats would betray the strike, we should not have called the General Strike. Even before the General Strike these people argued, as for example the liberal New Republic, that the various factors involved proved that “the employers will end the strike on their own terms”. ‘They predicted that “if it [the City] succeeds in controlling the supplying of the city’s needs…the strike fails and labor’s prestige suffers disastrously.”

In answer to this we must decisively say that only because of the general strike, did the fight of the maritime workers not end in a rout. The drive of the employers to stem the growing militancy was given a considerable setback and, everything considered, although the strike did not achieve its main objective, yet, at the end of the strike the working class as a whole found itself with tremendous gains in every way as compared to the period immediately prior to the beginning of the General Strike.

On July 11, under the tremendous pressure of the threatened General Strike, the employers changed their tune and announced that they were ready to deal with the sailors. After the “defeated” General Strike, the employers were forced to go further and acknowledge that the settlement of the demands of the longshoremen was contingent upon the settlement of the strike demands of the sailors and other marine workers.

Anyone acquainted with the whole history of the class struggle in the marine industry in the United States will understand that this was a tremendous victory—if only the workers will know how to follow up the advantage.

The second gain of the General Strike was a considerable raising of the standard of living of the workers all through California, not only in San Francisco where a good many workers won pay raises during the General Strike, but even in the agricultural fields, where the very fear of the spreading general strike caused the farm employers to raise wages from 17 1/2-20 1/2 cents to 30-35 cents an hour.

Thirdly, despite the concerted howling of the liberals, the unions, far from being crushed in San Francisco, have 8,000 more members than before the strike. Militancy, far from being killed, is now more widespread than ever, as is clearly shown by the anti-Red baiting resolutions adopted by local unions, by the actions of such locals as Painters Local 19, which for 12 or 14 years has taken no militant action, but which has now denounced the Central Labor Council fakers and proposed the organization of a working class newspaper, rejecting the proposal to accept the Labor Clarion, the official organ of the Labor Council, as that newspaper.

The New Republic, in its issue of July 25, says:

“It has been concluded that the general strike should be called for strictly limited periods only—for one day or two or three. The fact that this was not the type of strike in San Francisco indicated either that the leaders are inexperienced in the matter or that they are not acting on accepted theory.

“Unions under contract have exposed themselves to attack by violating their contracts. Fighting spirit and funds have been used up. Public opinion has been alienated.”

The best answer to all of this was contained in a leaflet issued by the International Longshoremen’s Association before the General Strike, which answered this problem in connection with the teamsters:

“The teamsters know that their contracts will not be worth the paper they are written on if the Industrial Association is able to force their open shop policy on the working class of this city.”

A General Strike limited to one or two days would certainly have completely failed of any objectives. It would only have provided the excuse for a great drive on the militants in the unions without giving the workers the valuable political lessons they learned from the conduct of the reactionary officials of the General Strike Committee.

This political experience is invaluable. We might divide the workers of San Francisco into three groupings: one group of which include the maritime workers, the needle trades workers, the cleaners and dyers, painters’ locals, and many other groups who by and large understand the treachery of the A. F. of L. leaders and have already taken action which clearly shows their own position for a militant policy.

The second group of workers are still confused although they have seen the treachery of the A. F. of L. leaders. They have no understanding of how it could be remedied, and regard this treachery purely as the misconduct of some individuals.

The third group of workers, and these constitute only a minority, have come to the conclusion, under the agitation of Bill Green and others, that general strikes are doomed to fail for all the various reasons given by the reactionaries.

The first group in these categories already represent a widely expanded basis for the activities of the militants as compared to the period prior to the strike. ‘The second and third groups must now become the objective for an active campaign of education so that the betrayal of the General Strike does not lead to discouragement and cynicism, but to a clear understanding and a more determined will to fight.

The importance of conducting that campaign is all the more clear because now the social-demagogues are making a drive to utilize this sentiment of the workers in their own interests. For example, Upton Sinclair would probably never have won the Democratic nomination were it not for the fact that many workers believe that he represented a protest against the Federal and State governments and their labor lieutenants. Judge Lazarus (the so-called liberal judge who released many strike prisoners) and many other capitalist demagogues are utilizing, in their own interests, the militant sentiment amongst the workers, which is by no means defeated. The Socialist Party made some ineffective effort to utilize the sentiment and has failed.

But the danger lies in the fact that although the Socialist Party, because of its weaknesses, will only be able to use social-demagogy to a very small degree, Sinclair and other such elements will become powerful social-demagogic and social-fascist factors. On the political field, therefore, as well as in the trade unions and elsewhere, the main enemy are these social-demagogues.

THE FIGHT NOW

From this General Strike, one thing stands out above all others, and that is that the defeat of social-fascism and the A. F. of L. bureaucracy is a prime condition for the victory of the working class, whether that victory be the final victory in the overthrow of capitalism, or only a gain in hours and wages.

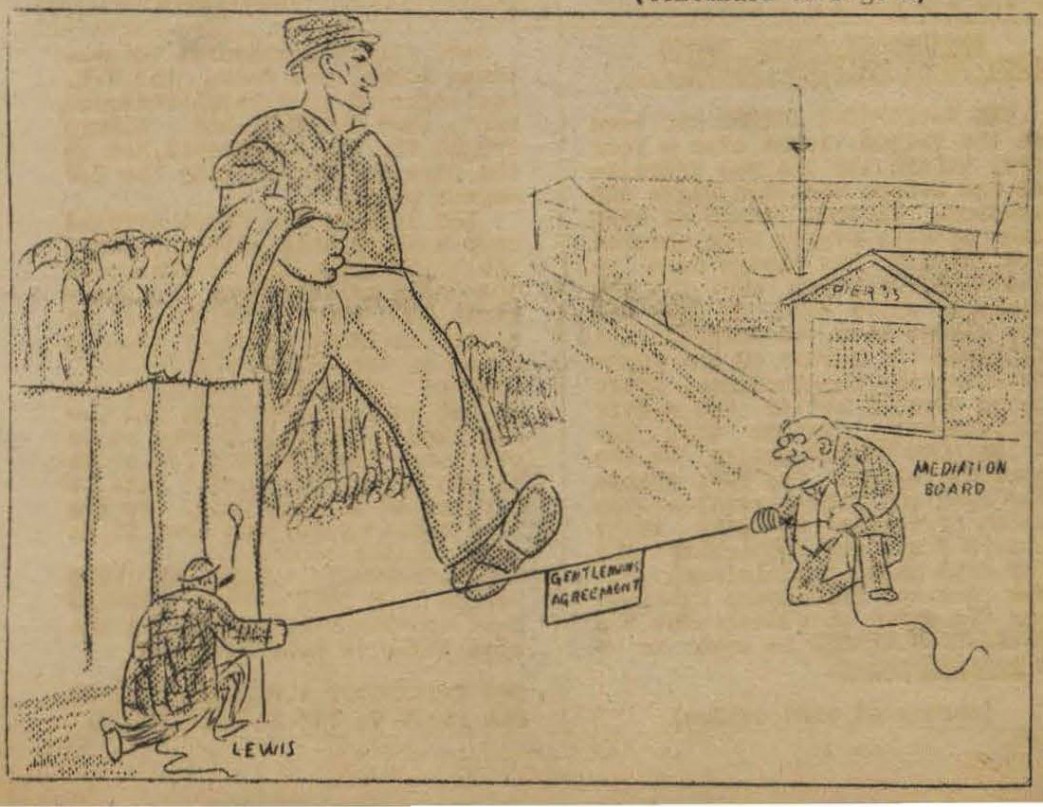

After the General Strike, the maritime strike continued under an agreement for arbitration which the workers in the maritime industry were forced to accept. In San Francisco and those other ports where the militant leadership was strong, the waterfront is largely in control of the local union. In those places, however, such as San Pedro where the militant leadership is weak, discrimination against the militant workers is being practiced widespread. The reactionaries in the longshoremen’s union are continuing their policy of working hand and glove with the shipowners. When longshoremen, for example, refused to load ships manned by scab seamen, Lewis, president of the District Council, issued a letter saying:

“It behooves every local organization to see that all ships are worked regardless of the nature of the dispute. In the case of nonunion seamen being employed on board ships, the seamen also have the machinery set up for the handling of their grievances.”

In California itself, the liberals have confidently predicted that labor is crushed and that for a long time no more strikes will take place. An effort is being made by the fakers to split the unity of the West Coast seamen and organize a Northwest Federation of the I.L.A. But against this, the militancy of the workers has remained solid. The workers on the San Francisco waterfront have shown that they are far from crushed. They have succeeded in eliminating all but a very few of the scabs from the front and these scabs are mostly previously walking bosses. In answer to the predictions about “an end to all strikes”, we have the strike of 6,000 lettuce and apple workers who struck three weeks after the end of the General Strike. In answer to Lewis’ circular and the attempt to split the unity of the West Coast, the militants in the locals are gaining strength every day and the likelihood is that the fall elections of the I.L.A. on the West Coast will show a large number of militants elected to offices in most ports.

In answer to the predictions about the “crushing of labor”, the workers have shown everywhere increased trade union organization, greater militancy on the political field, and despite its being a post strike period, great militancy and the desire to struggle.

The analysis of the General Strike reveals the fact that, far from being a mistake, that strike is a milestone in the revolutionary development of the American working class. As such, its lessons must be grasped by every member of the Communist Party so that we can forge ahead to leadership in the strike struggles which are developing into major attacks (both economic and political) upon the capitalist system. The Strike Resolution of the Central Committee of our Party brings forward sharply the seriousness of the impending struggles and the imperative duty of the Communist Party in these struggles. It points out that the organization and leadership of these struggles can be carried through in the factories and the trade unions only “along the lines of the Party policy of concentration in the main industries, districts, and factories”; that we must “finally overcome and root out all underestimation of work in the reformist unions”; that we must “strengthen the work and leadership of the T.U.U.L. and other independent unions under our influence, and develop the united front of all workers, organized and unorganized”, The Strike Resolution emphasizes the need to mobilize the workers against the treacherous A. F. of L. bureaucracy and all those trying to prevent such a struggle; the need to bring vital political issues into every strike so that the masses may clearly understand the “growing fascist and semi-fascist methods of suppressing strikes” to which the national and local governments resort, so that the current of antifascist struggle may penetrate the strike struggles.

No less must the role and actions of the A. F. of L. bureaucrats (aided by the S.P. leaders and the renegades) be exposed before the masses—their alliance with the New Deal and its arbitration policies. Above all, the San Francisco strike revealed the importance of raising the political level of our Party, which means that the role of the Party in winning the majority of the working class to the banner of Communism must be impressed upon our Party membership. For this strike, in the words of the Strike Resolution, “proved beyond a shadow of doubt that the hiding of the face of the Party, the capitulation before the Red-baiting campaigns of the enemy, must lead to defeat, while the taking up of the bosses’ attack on the Party, answering all questions to the workers, explaining to the toiling masses the whole program of the Party, leads to the very attack of the bosses, their hostile propaganda, being converted into a means of interesting new masses in Communism and winning them to our side” —winning them for the struggle for Soviet Power.

There are a number of journals with this name in the history of the movement. This ‘Communist’ was the main theoretical journal of the Communist Party from 1927 until 1944. Its origins lie with the folding of The Liberator, Soviet Russia Pictorial, and Labor Herald together into Workers Monthly as the new unified Communist Party’s official cultural and discussion magazine in November, 1924. Workers Monthly became The Communist in March ,1927 and was also published monthly. The Communist contains the most thorough archive of the Communist Party’s positions and thinking during its run. The New Masses became the main cultural vehicle for the CP and the Communist, though it began with with more vibrancy and discussion, became increasingly an organ of Comintern and CP program. Over its run the tagline went from “A Theoretical Magazine for the Discussion of Revolutionary Problems” to “A Magazine of the Theory and Practice of Marxism-Leninism” to “A Marxist Magazine Devoted to Advancement of Democratic Thought and Action.” The aesthetic of the journal also changed dramatically over its years. Editors included Earl Browder, Alex Bittelman, Max Bedacht, and Bertram D. Wolfe.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v13n10-oct-1934-communist.pdf