William F. Dunne travels to the People’s Republic of Mongolia to attend a trade union conference in 1929.

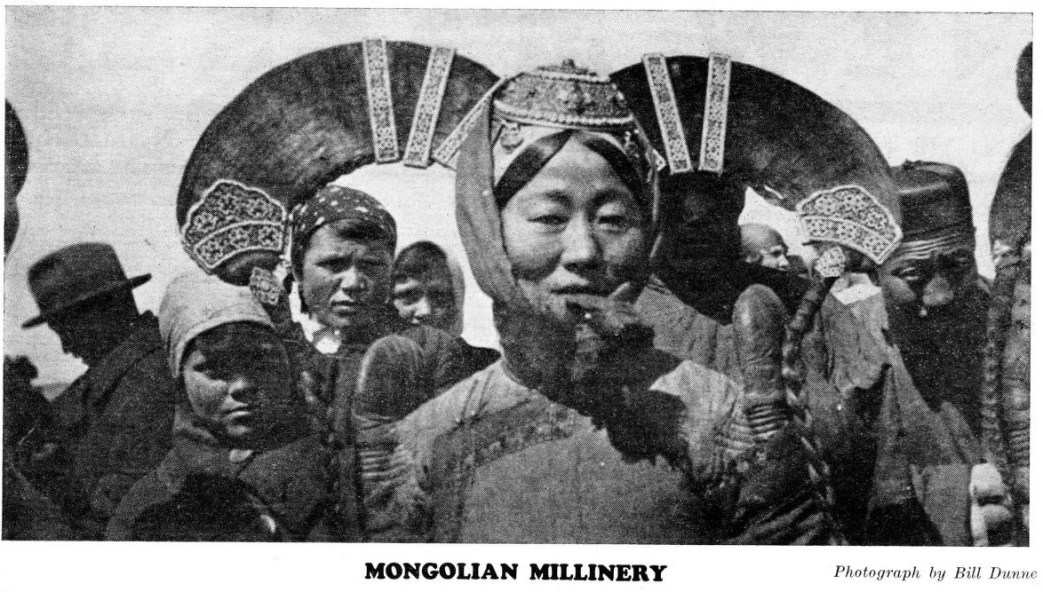

‘The Red Tide in Mongolia’ by William F. Dunne from New Masses. Vol. 4 No. 12. May, 1929.

We tore across the great Mongolian plain at 100 kilometers per hour — a Czecho- Slovak, a Buriat-Mongol and an American. Our driver knew the military highway which runs from Verkneuudinsk on the Trans-Siberian to Ulan-Bator as I know the palm of my hand. He had guided careening military trucks loaded with munitions for the Kuomintang armies over every foot of its 400 miles. Driving the same car we were in — a huge Fiat — he had made the 400 miles in 7 hours. He cursed rich Russian curses when he had to slow down to 70 kilometers.

Straight south we drove — across the broad and turbulent Sdlenge, crossing by a ferry operated by prisoners who had violated the laws of the Autonomous Soviet Republic of Buriat-Mongolia. Straight south, through the rich farming section of Buriat-Mongolia, through fields of ripe grain, through populous villages, past great herds of cattle, sheep and goats. We passed the great Buddhist lamastery where the lamas now act only as guides for the students and the curious, and doubtless wonder about this Communism that has proved to be more powerful than their ancient faith.

We stopped for lunch at a little village where the former priest is now the innkeeper. Then we began to climb out of the plain. An hour later we looked back. The great valley was in shadow but the sun shown down on the huge white mosque in the village we had left behind. No houses were visible, only the gleaming domes of the mosque could be seen. It rose majestically from the green-brown plain, alone and beautiful to see. All the mystery and might of old central Asia was incorporated in it. It stood like something out of a book of fairy-tales — unreasonable, useless, but lovely and impressive. One understood the power of the religion it symbolized upon the minds of primitive peoples — the power that is waning fast as the teachings of Lenin turn the minds of the masses of central Asia from servility to the living gods of Buddhism and its debauching slave philosophy to the bright, stern struggle against feudalism and imperialism.

From Troitskassovsk, the beautiful little border city, with its huge white market and its ethnological museum, presided over by an old professor whose love for his priceless collection shines forth in every word and gesture, through Kiachta, once a city of millionaires and the world’s tea-trading center before white men came to America, to Altam- Bulak, the frontier city of the Peoples Republic of Mongolia. Altam-Bulak is only two miles from Troitskassovsk but we were in another world. Yurts — the round, felt covered houses of the Mongols — Chinese traders, Mongol bowmen playing their national game in the public square with blunt arrows, soldiers whose caps no longer bore the hammer and sickle but the lotus flower — the Mongol national emblem — made the two miles seem ten thousand.

We went by airplane from Altam-Bulak to Ulan-Bator (Urga) — the City of Red Giants. We flew over the dark mountains, the winding streams and the wide valleys through which the hordes of Genghis Khan toiled laboriously on their westward march of conquest and desolation, to Urga, once the capital of Genghis Khan — a city that was flourishing and dominating the caravan routes of central Asia 600 years before Columbus found America by accident.

Urga is a city of strange contrasts. It has the oldest and newest in government, in customs, in transportation and communication. The descendants of the Mongol people who conquered half the world by fire and sword, the hard-riding, helmeted bowmen whose very name struck terror to millions, the followers of the ox-tail standards which were raised on the ruins of a thousand cities and dyed red in the crimson tide of ten thousand battles — now sing the International and live in peace with their traditional enemy to the north — Russia.

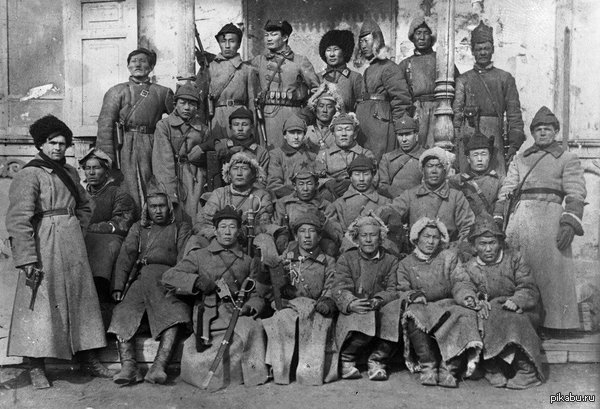

The Mongolian Peoples Revolutionary Party rules the Republic and rules it well — after leading the bloody struggle of the Mongol masses against Chinese tyrants, White Guard Russian butchers like Baron Ungern- Sternberg, the dynasty of the Mongol princes and the religio-feudal despotism of the Buddhist lamas. The path traveled by the Mongol masses from 1921 to 1925 is stained scarlet with the blood of thousands of Mongol herdsmen who, hearing the echoes of the proletarian revolution in Russia, made the mountains and the valleys of their country ring with demands for liberation and with the rattle of rifle and machine-gun fire by which they gave life to their demands over the dead bodies of feudal retainers and imperialist mercenaries.

The Peoples Republic of Mongolia is the only former colony in the world outside the Soviet Union where a non-capitalist society is emerging from the old feudal structure. In the republic, as large as France, Germany and Spain together, there are but 800,000 people. There are only the first faint beginnings of a proletariat. There is no big bourgeoisie. There is no agriculture worthy the name. There is not a mile of railroad in the country. The people are half-nomadic. They live and dress like they did 1000 years ago — with this exception:

The government is their government, the governing party is their party , and they can now buy their clothes from government cooperatives which are displacing private capitalist enterprises.

The masses are learning to read and write — and to govern in their own name and in their own interest. The cultural level is being raised. In Urga there is a university and various other grades of schools. The youth get military training and they de fend the revolution. The army is a peoples army. It is a good little army— with airplanes, artillery and tanks. Throughout the country side are schools. In the provinces the people themselves administer the local governments. The government departments are based still on the old tribal subdivisions — the bak, a unit of ten or twenty, (the old family unit) the somun, composed of ten baks, the hoshun, made up of a certain number of somuns, and the aimaks, composed of hoshuns. The aimaks have rough territorial outlines corresponding to the regions formerly held by the tribes. But all this is being reshaped into the new order more rapidly than one would think possible. Let some one try to halt this development and he incurs the swift anger of the Mongol masses. They have learned through bitter struggles how to deal with traitors and the justice of the Mongol people today is quick and sure.

The trade union congress (the unions, organized two years ago, have 600 members) the enlarged meeting of the Peoples Party executive and the seventh congress of the party itself gave concrete proof of the determination of the Mongol masses to root out the last remnants of feudalism and unmask and punish with revolutionary justice all those who attempt to betray them to imperialism.

Following the betrayal and defeat of the Chinese liberation movement in its first phase there were naturally repercussions in Mongolia. Sections of the party leadership entered into negotiations with Chiang Kai Shek; others into negotiations with Japan; the relations with the Soviet Union were strained; the feudal elements and the private traders conspired with the ever-restless lamas. (There are approximately 150,000 of these vicious drones in the country— 18,000 in Urga alone out of a total population of 60,000.)

In the party leadership these counter-revolutionary elements found aid and comfort. The party itself is a bloc of classes and for a time the real issues were concealed from the masses. Plots and rumors of plots filled the air. Conspiracies were discovered in the army. The government even went so far as to give a Japanese military attaché permission to come to Urga. The lamas staged demonstration after demonstration. Rank and file members and their leaders were arrested and imprisoned. Discussion before the party congress was prohibited. Bureaucracy, counter-revolutionary bureaucracy, was in the saddle and the imperialist press in the Far East was jubilant. Great Britain saw the road from Tibet to the Soviet Frontier opening up, Japan saw her long coveted road from Manchuria through Mongolia no longer held by a Peoples Revolutionary Party and government.

But the Mongol herdsmen were not asleep on the arms with which they had won their freedom. The trade union congress struck the first note of struggle. Once a people breaks through the crust of feudal tradition in this day and age, it is a big mistake to think that primitive culture necessarily means primitive political methods and understanding.

The trade union congress lasted 12 days. The procedure was strange to a Westerner but with it the masses got results. After the representative of the Profintern had made his report the delegates handed in written questions dealing with every phase and detail of the international labor movement and their application to the special problems in Mongolia. The representative was required to answer every one of these questions. He spoke for three consecutive days replying. There was no other order of business until he finished. Only then did the discussion on the situation and the tasks of the trade unions begin. It was a thorough discussion and was conducted in Mongol, Chinese, Russian and English. When it was finished the secretary of the central committee of the party (one of the leaders of the extreme right) nominated a list of candidates for the central executive committee of the unions. Only one of his candidates was elected. The delegates defeated every supporter of the opportunist wing in the party leadership.

In the enlarged meeting of the party executive which lasted for ten days the right wing was politically defeated. Urga was full of delegates and party members who came to rescue the party and the government from the counter-revolutionary elements.

The delegation from the Communist International (the Mongolian Peoples Revolutionary Party is fraternally affiliated to the Comintern) was besieged night and day by delegations enraged by the actions of the party leadership. Open discussion was forced. Students demonstrated against the central committee for the release of imprisoned comrades of the left. Emergency situations became commonplaces. Late one night it was necessary to hold huge open air mass meetings, for all the army departments, at which the Comintern delegation spoke. The prisoners were released. The tension relaxed somewhat. Then came news of a plot of the lamas. Some were arrested. The party congress opened.

Following the reports more than 2000 questions were asked by the 200 delegates, 20 of whom were women — their presence itself a living symbol of the deep roots of the revolution in Central Asia. Every question was answered. The discussion began and every delegate spoke at least once. The congress lasted 52 days.

The counter-revolutionary elements were completely defeated. Perhaps the best evidence of this is the fact that La Gan, one of the left leaders who was jailed, and whom the right were talking of executing, was elected chairman of the Control Commission. He is a very determined comrade and the job of being a Japanese agent in Mongolia at present must be placed in the category of extra hazardous occupations.

The Peoples House, built like a huge yurt, the bright robes and sashes of the delegates and onlookers and their queer curved Mongol boots, the Mongol tongue, the jade-mouted pipes with their tiny bowls, the haze of evil-smelling Mongol tobacco, the fur coats of the military delegates contrasting strikingly with their modern arms — all formed a bizarre background^ for the revolutionary political discussion with its Marxian terminology. The congress plowed through its business of correcting the errors of the leadership and laying down a clear revolutionary line with the resistless force of the ancient armies which swept all before them up to the Danube. There was some excitement when an anonymous letter, threatening all members of the presidium with death, was read, there was some more when someone fired a shot through the window right back of the table where the presidium sat, there was anger when spies were discovered, but these were only incidents which convinced the delegates of the necessity of a firmer policy.

There were endless banquets, ranging from the elaborate one in the Soviet Embassy on the 11th Anniversary of the November Revolution to the numerous Mongolian feasts consisting principally of roast and boiled lamb and kumyss. (Fermented mare’s milk.)

There was the great celebration in the public square in Urga, (twice as big as the Red Square in Moscow) on the anniversary of the Russian Revolution when we walked more than a mile around the square with our thinly gloved hands at salute in a temperature of 20 degrees below zero. There were the long lines of Mongol youngsters, none more than three feet high, clothed in long sheepskin lined coats and caps, singing the International at the top of their voices.

There were the sturdy women, dressed exactly like their men, except that occasionally one sees an ear-ring swinging below bobbed black hair. There was my Mongol translator who had been with the Roy Chapman Andrews scientific expedition which every Mongol says was prospecting for oil. There were the opportunist leaders with Europeanized manners who now are gone.

Of it all Urga itself is the most indicative of the march of the revolution into Central Asia. Old, surrounded by mountains and valleys strewn with the bones and soaked with the blood of humble millions who down through the ages have died by starvation, fire and battle at the hands of merciless conquerors, Urga, old when Europe was young, symbolizes the passing of its past and the upsurge of the new order.

In the early morning of an autumn day Urga is clothed in a pearly mist — half fog, half dust. The smell of sheep and camels is strong and acrid but not unpleasant. The gilded roofs of the mosques, above the mist, gleam in the sun. From north and south and east come great camel caravans. Long strings of two-wheeled carts, without a piece of iron in their structure, and drawn by yaks or oxen cut across the square from all directions. Hundreds of Mongol horsemen with saddles of red and green leather, with robes of every color of the rainbow clatter up and down. Chinese workers, with the carcass of a freshly slaughtered sheep across their shoulders hurry to their own section of the city. The smoke rises straight from a thousand yurts.

Through the square run telegraph and telephone lines. Automobiles with their horns shrieking, trucks loaded mountain high with hides and wool, drive through at breakneck speed. At the electric station the current is switched off from the street lamps. Overhead an airplane drones its way north to the Trans-Siberian or perhaps east to Kalgan. In a few hours the daily news sheet, its contents secured from the radio station, one of the most powerful in the world, will he delivered by a Mongol whose racial resemblance to the American Indians is obvious, who will be clad in the traditional Mongol costume but who will be driving a Dodge car. The government cooperatives will soon be open and Monzenkop — the government trust-will be buying furs, hides and wool from Mongol trappers and herdsmen who a few years ago had to deal with and submit to the cheating of private dealers.

A regiment of the Peoples Army debouches into the square — off for a practice march. The red star with its Mongol emblem on their caps. Over the new municipal building, over the trade union headquarters, over the Mongol Peoples Publishing House, over the Peoples House, over the headquarters of the Revolutionary Youth, over the Peoples University, over the Peoples Government House, over the headquarters of the Mongol Peoples Revolutionary Party, fly crimson flags.

From feudalism and a primitive, nomadic culture to a Peoples Revolutionary Government? From Buddhism’s pacifism for the masses to armed struggle for liberation? From tribalism to a non-capitalist development which roots itself in and rallies the masses? From centuries-old enmity to the Russian in the North to friendship, alliance and cooperation on a basis of equality? From vassals of imperialism and their feudal allies to the status of free men? From a backward, oppressed people sunk in ignorance and misery by Buddhism and feudalism to an integral part of the world revolution? (Before the revolution the “Living Buddha” in Urga had 100,000 serfs scattered throughout the land.) All this in seven years?

How is it possible?

The explanation is to be found, in simple language understandable to everyone, in the section of the program of the Communist International which deals with questions of the revolution in colonial and semi-colonial countries, and which is based on the theses on the National and Colonial Question drafted by Lenin for the Second Congress of the International:

“In still more backward countries where there are no wage workers or very few, where the majority of the population still live in tribal conditions, where survivals of the primitive tribal forms still exist, where the primary role of foreign imperialism is that of military occupation and usurpation of the land, the central task is to fight for national independence. Victorious national uprisings in these countries may open the way for their direct development towards socialism and their avoiding the stage of capitalism, provided real, powerful assistance is rendered to them by the countries in which the proletarian dictatorship is established.”

It will be noticed that the paragraph quoted deals with the question of revolutions in the types of countries cited and assistance from the proletarian dictatorships in a general way.

But we are dealing with a concrete question: How has the development in Mongolia taken place and how has the revolution survived in spite of its primitive heritage and imperialist and feudal pressure?

The Communist program answers this concrete question without mincing words:

“Thus, in the epoch in which the proletariat in the most developed capitalist countries is confronted with the immediate task of capturing power, in which the dictatorship of the proletariat is already established in the U.S.S.R. and is a factor of world significance, which has brought into being by the penetration of world capitalism, may lead to a socialist development — notwithstanding the immaturity of social relationships in these countries by themselves — provided they receive the assistance and support of the proletarian dictatorship and of the international proletarian movement generally.”

There you have it. The Peoples Republic of Mongolia is part of the world revolution, it fought its battle for liberation side by side with the masses of the Soviet Union, it lives and grows under the protecting arm of the proletarian dictatorship.

Its 4000 kilometers of frontier joining the Soviet Union are not points of hostility but a steel band of revolutionary solidarity with the Russian revolution and the international proletarian revolution.

The Red Tide runs fast and strong in the homeland of Genghis Khan.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s to early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway, Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and more journalistic in its tone.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1929/v04n12-may-1929-New-Masses.pdf