In many ways the 1929 Communist-inspired textile strike in Gastonia, North Carolina was a harbinger of the C.I.O. unionization drive of later 1930s as it reached into previously unorganized territory and workers. The first substantial strike of the National Textile Workers Union led the struggle with the Workers International Relief setting up a tent colony, and the International Labor Defense providing legal support. An intense and dramatic struggle, death, jail, exile, and death penalty trials followed with Communist Party activists, notably women, playing central roles. Former miner and veteran labor reporter Tom Tippett writes from the scene for A.J. Muste’s ‘Labor Age.’

‘War In Gastonia!’ by Tom Tippett from Labor Age. Vol 18 No. 7. July, 1929.

Fourteen Workers Face Murder Charge

AROUND the middle of July 14 union men and women will come to trial in North Carolina charged with the murder of Chief of Police O. F. Aderholt of Gastonia. Unless a miracle happens some of them will be convicted and go either to the electric chair or to prison. The Gastonia trial will then take its place in the history of American labor with the Haymarket Riot, the Centralia Trial, the Tom Mooney Case, and the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti. All the cases are similar and have to do at bottom not with the individuals named in the record but with those who have and those who have not in these United States.

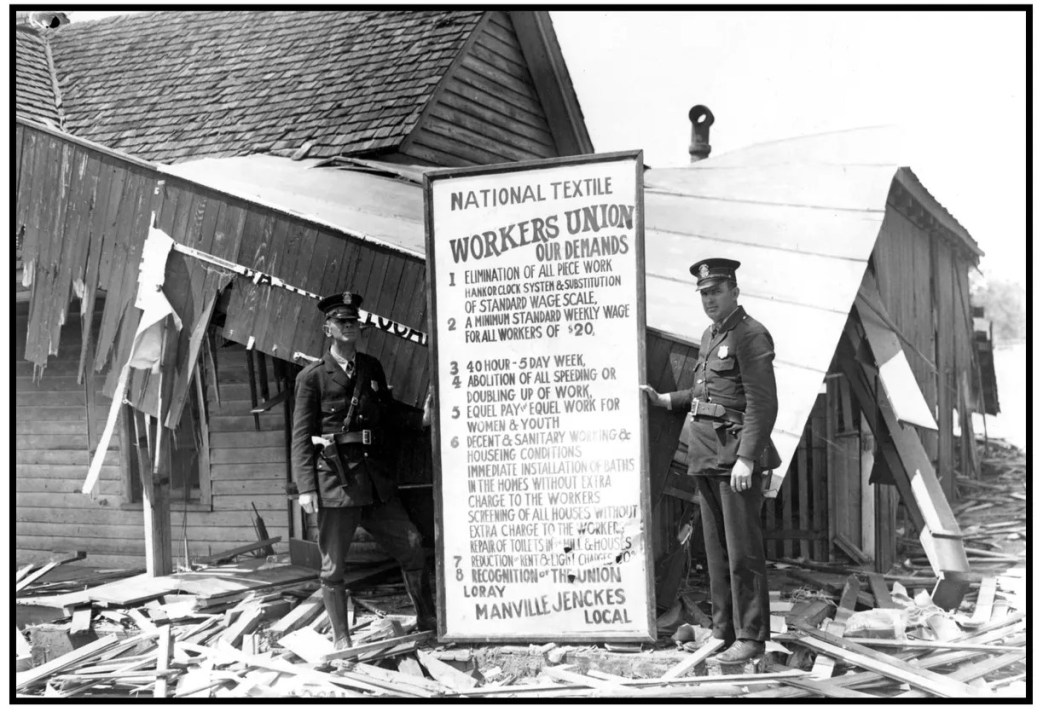

Circumstances leading up to the Gastonia trial began when the National Textile Workers’ Union sent organizers into the South in behalf of that organization. It could not have selected a better field for operation. Gastonia is a city of 33,000 inhabitants. There are 52 textile mills and no other industries in the town. Everybody lives in one way or another from textiles. The largest textile mills in America are located in the Loray mill village, situated within the city limits of Gastonia. It manufactures yarn and weaves automobile tire fabric with 2,200 employees at work on the two operations under the same roof. The big Loray mill is one of a chain owned by the Manville-Jenks Co. of Pawtuckett, R, I.

Ruthless Domination

Some of the worst labor conditions in North Carolina prevail in this mill. There is a mill village with over-crowded houses, unsanitary conditions, and the worst aspects of paternalism. The state’s 14 year age child labor law is violated. Whole families, sometimes representing three generations, work in the mills. Individual workers earn from 50 cents to $3 a day. $9 to $12 is about the average weekly wage for men and women. There is a night shift of 11 and 12 hours. Company credit and company stores keep many families always in debt to the mill. There are company boarding houses, company playgrounds, company churches, and all the rest. Textile mills dominate every phase of life in Gastonia. Starting with the one daily newspaper, the Gazette, the hand of the textile owner can be plainly seen in the civic clubs, schools, court house (Gastonia is a county seat) and in the churches. The working conditions cited here give mute testimony to what workers in the South may expect when the undisputed will of textile manufacturers has its way.

The mill workers who have been referred to here as the “cess pool” of humanity by a visiting textile magnate, are all of pure Anglo-Saxon stock who have lived for generations back in the rural sections, and are now going through the painful transition from an independence on the land to a poverty-stricken wage earning class. By and large they are a simple hardworking friendly folk with a deep sense of class solidarity inherited from the hills. They are considered by the upper strata as inferior stock and are looked down upon by this so-called better element. I have never seen less cause for such an attitude. In native qualities these mill people are quite above the “average man.”

An Armed Camp

Into such a setting came the union organizers in March. By April 1 the Manville-Jenks espionage system brought about the dismissal of a handful of people who had joined the N.T.W.U. This precipitated a premature strike. More than 1,000 workers joined the walk-out. The sheriff called for troops, and within a week the Loray Mill Village was a military camp. Company after company of Militia came in, opened headquarters in the Young Men’s Christian Association building and pitched their tents in the yard of the mill. The Gazette spewed forth hysterical condemnation of the union, proclaiming that the vanguard of the revolution was beating at the city gates…the fight was on.

Albert Weisbord mounted the strikers’ platform. Listen to him speak: “This strike is the first shot in a battle which will be heard around the world. It will prove as important in transforming the social and political life of this country as the Civil War itself. These yellow aristocrats have ground you down for centuries. They went out to the farms and mountains to offer you high wages and good conditions, but you have a Chinese standard of living. In 1850 the United States government announced a 10-hour day for navy yards and public works — and here you are so far behind the times that you are working 12 hours a day. We have come to Gastonia to help you in your struggle for existence. Make this strike a flame that will sweep from Gastonia to Atlanta, and beyond, so that we can have at least 200,000 cotton mill workers on strike You can’t get ahead by yourself. Stick together! Don’t listen to the poison of the bosses — extend the strike over the whole country-side. We need mass action!”

Weisbord is from the North. His union is outside the pale of the American Federation of Labor. The Gazette called it a communist union, and used all the anti-social epithets which ignorant people always use when opposing unionism. All of which could have been considered obstacles in Weisbord’s southern path, but the workers rallied to him en masse.

The N.T.W.U. was formulated by the Communist Party and its organizers, in the main, are members of the Communist Party or its allied organizations. But the union program in Gastonia was far from communistic. It was a militant class conscious union and nothing more. Weisbord’s speech set the pace for strike activity. He left the strike in other hands and the Loray mill workers were in the forefront of all union activity.

The mill threatened the workers with the soldiers, and then an unheard of tactic (in America) was employed by the union. It issued an appeal for mutiny to the soldiers. “Workers of the National Guard!” the statement said, “Do not accept the orders of capitalist murderers but stand fast when the order is given for strike duty. Refuse to shoot your fathers and brothers on the picket lines! Don’t be a strikebreaking scab! Fight with your class, the strikers, against our common enemy, the textile bosses. Join us on the picket line and help win this strike. Do not obey the orders of the bosses! Do not shoot us, the strikers!”

Why Soldiers Were Withdrawn

The amazing thing about this appeal to the soldiers is that it worked. They did refuse to shoot or manhandle the strikers. It is true that the soldiers slept within ear-shot of a masked mob, organized, says the union, by the null, when it wrecked the union’s headquarters and destroyed food for strike relief in the commissary: But many of the soldiers resented this brutality — and then, the powers that be sent all the soldiers home. The day after the soldiers left, however, an imported brand of deputy appeared in the strike zone and began a systemized reign of terror which has not subsided.

Strikers were beaten up and tossed into jail without discrimination — women as well as men. All strike activity was opposed by force. No picketing was permitted and strikers’ parades were broken up by deputies’ clubs and bayonets all during the strike. It was one of these “imported” deputies who beat into unconsciousness a young news reporter from the Charlotte Observer. In spite of this opposition the strike spread. One mill after another in and around Gastonia came out on strike.

The union is new. It is small. It lacks funds and is isolated from the general labor movement. It did not have one articulate friend, in this section, outside of its own ranks. Because of this the strike toppled over of its own weight. But the union hung on at the Manville-Jenks plant.

Many families were evicted from their homes. The union brought in tents and the first “tent colony” appeared in an American textile strike. The tents were erected on a lot rented by the union which built a new hall to take the place of the headquarters that was wrecked by the mob. And the strike hung on with an armed union guard as the only protection for union property.

On the evening of June 7 the usual union meeting was held. Inspiration speeches were made by organizers; a parade formed and began a march through the village. The deputies broke this parade up, by force, as was their usual custom. And while that police violence was going on another group of police officers headed by Chief O.F. Aderholt appeared at the tent colony. A union guard lawfully requested a warrant. The police had no warrant but disarmed the guard by force. Other police simultaneously entered the union lot and began chasing the union people through the tent colony. Shots were fired by both sides and much circumstantial evidence indicates that the police started the firing. Five people fell in the battle — a union man and four policemen. Chief Aderholt died the next morning from his wounds. The other policemen were slightly wounded. The union organizer, Joseph Harrison, is seriously wounded lying in a Gastonia hospital. Anti-union forces say the union deliberately planned to shoot the police and had telephoned for them to come and put down a quarrel among the strikers in the colony. The charge is absurd and does not explain why the police forcibly entered the colony after they arrived and found no quarrel in evidence.

When the preliminary hearing was held on June 19 this point was proven when a lawyer for the union asked Adam Hord, who was one of the raiders and who has since been acting chief of police, this question:

“There wasn’t any trouble until one of the members of your force started to disarm one of the men on private property. Is that right?”

To that question the acting chief of police answered, without the slightest hesitation: ”Yes, that’s right.” According to the United States constitution that answer should have dismissed the case against the prisoners, but since this is an industrial fight between mill owners and mill workers constitutional guarantees did not matter and 14 members of the union, including all the officers, were indicted for murder and will be tried for that offense on July 22.

If this trial puts an end to the National Textile Workers’ Union it will not settle the real cause of the trouble. Strikes have broken out again in North and South Carolina. As I write at least 10,000 workers are in revolt against the conditions which underly the Gastonia case. When mill owners make some concessions to their workers, when they reduce the 11 and 12 hour work day; when they increase the $9 and $12 weekly wage scales; when they recognize the right of southern mill people to participate in determining conditions under which they labor some kind of peace may come. But not before. For the industrial revolution has also come to Dixie Land.

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v28n07-Jul-1929-Labor%20Age.pdf