Written for the twentieth anniversary of Marx’s death and printed in Iskra on March 1, 1903 this excellent essay by Georg Plekhanov was deservedly picked by David Riazanov to begin discussion of Marx’s politics for his 1927 ‘Symposium.’

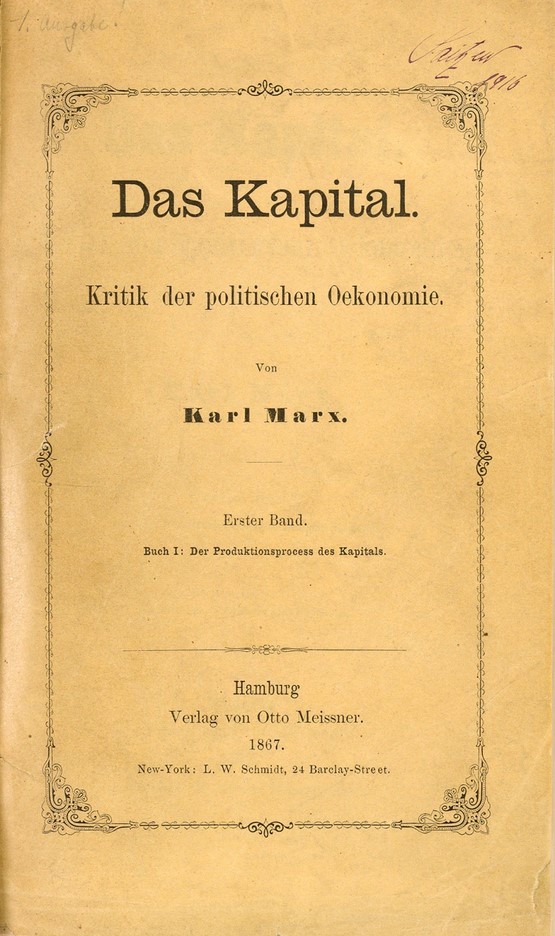

‘Karl Marx’ (1903) by Georg Plekhanov from Karl Marx: Man, Thinker, and Revolutionist; a Symposium edited by David Riazanov. International Publishers, New York. 1927.

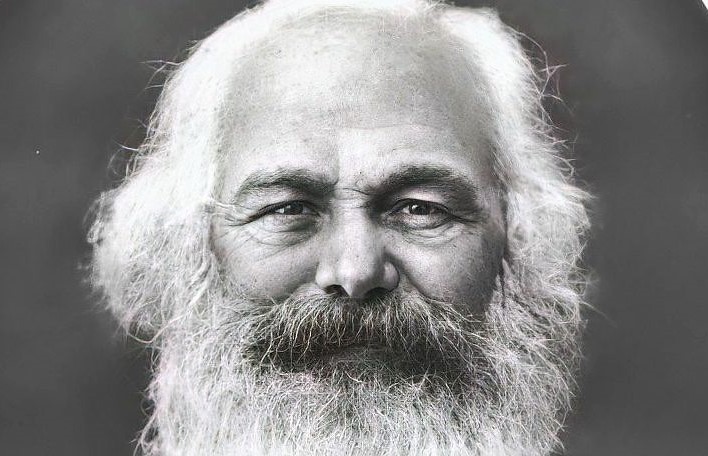

The thirty-fifth number of “Iskra” appears on the twentieth anniversary of the death of Karl Marx, to whom the first place must therefore be allotted. If it is true that the great international working-class movement was the most remarkable social phenomenon of the nineteenth century, it follows that the founder of the International Workingmen’s Association was the most remarkable man of that century. A fighter and a thinker rolled into one, he not only organised the forces of the international army of the workers, but forged for that army (in collaboration with his faithful friend Friedrich Engels) the powerful spiritual weapon with whose aid it has already inflicted many defeats upon its enemy, and will ere long win a complete victory. If socialism has become scientific, we owe this to Karl Marx. Furthermore, if awakened proletarians are now fully aware that the social revolution is an essential preliminary to the final deliverance of the working class, and that this revolution must be brought about by the workers themselves; if they now show themselves to be the implacable and indefatigable enemies of the bourgeois system of society — these things are due to the influence of scientific socialism. From the practical point of view, scientific socialism differs from utopian socialism in this respect, that it lays bare the fundamental contradictions of the capitalist social system, ruthlessly exposing the futility of the various schemes (sometimes very ingenious, and always extremely benevolent!) of social reform brought forward by utopian socialists of one school or another — schemes offered by them as the one and only way of putting an end to class struggles and making peace between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. The workers to-day, having adopted the theory of scientific socialism, and remaining true to its spirit, cannot but be revolutionists both in thought and feeling, cannot fail to belong to the most “dangerous” variety of revolutionists.

Marx had the honour of being more detested by the bourgeoisie than any other socialist of the nineteenth century. On the other hand it was his enviable lot to be the teacher most highly esteemed by the proletariat during the same epoch. At the very time when the hatred of the exploiters was concentrated on him, his name was held in the greatest possible honour by the exploited. Now, in the opening years of the twentieth century, the class-conscious workers of all lands look upon him as their teacher, and regard him with pride as one of the most universal and profound geniuses, one of the most noble and self-sacrificing personalities, known to history.

“The saint in whose memory the first of May celebrations have been instituted is called Karl Marx,” wrote one of the Viennese capitalist newspapers in the end of April, 1890. In very truth, the huge May Day demonstrations organised every year by the workers throughout the world, though not designed for the express purpose of paying honour to Karl Marx, are a gigantic tribute to the memory of the man of genius whose program united into one harmonious whole the daily Struggle of the workers for an improvement of the conditions on which they sell their labour power, and the revolutionary Struggle against the existing economic order. But the celebration has nothing in common with religious festivals; for the workers of our day honour their “saints” the more in proportion as they have tended to bring nearer the happy day when a freed humanity will establish the kingdom of heaven upon earth, and will leave the heavens at the disposal of the angels and the birds.

Among the malicious fables circulated regarding Marx, must be numbered the absurd Statement that the author of Capital was hostile to the Russians. But it is quite true that he was an avowed enemy of Russian Tsarism, which has always played the odious part of international policeman, ready to crush any movement for the liberation of the oppressed, wherever it might begin.

Marx watched with intense interest every genuine manifestation of internal development in Russia, and showed in this respect a fundamental knowledge of the matter in hand such as was then possessed by hardly any of his contemporaries in western Europe. Lessner, the German worker, in his “A Worker’s Memories of Karl Marx,” tells us how delighted Marx was when the Russian ‘ translation of Capital was published, and how glad he was to know that there were persons in Russia able to understand and to spread the ideas of scientific socialism. The preface to the Russian translation of the Communist Manifesto shows how Marx’s sympathy with the Russian revolutionists and his ardent longing for their speedy victory had led him to undertake a notable reconsideration of our revolutionary movement of those days. His relations with Lopatin and Hartman prove how warm a welcome Russian exiles could count on receiving in his hospitable home. (1) His quarrel with Herzen was partly due to a chance disagreement, but in part to Marx’s well-grounded distrust of the Slavophil socialism whose herald in western European literature our brilliant fellow-countryman unfortunately became under the influence of the overwhelming disappointments of the years 1848-1851. Marx’s onslaught on Slavophil socialism in the first edition of the first volume of Capital deserves praise rather than blame, especially nowadays, when this kind of socialism has been revived in the party program of the so-called social revolutionaries. Finally, as regards the fierce struggle between Marx and Bakunin in the International Workingmen’s Association, this had nothing to do with the Russian origin of the anarchist champion, and finds a much simpler explanation in the antithesis between the two men’s views. (2) When the publications of the Deliverance of Labour group began to spread social-democratic ideas among the Russian revolutionists, Engels, in a letter to Vera Zassulich, said it was a pity that this had not happened while Marx was alive, for Marx (said Engels) would have extended a hearty welcome to the literary undertakings of the group. What would the distinguished author of Capital have said if he could have lived on to our own day, when so many of the Russian workers have become his followers? How joyful he would have been, could he have heard of such incidents as that which recently happened at Rostov-on-the-Don. In Marx’s lifetime, a Russian Marxist was a rarity, and the best that such a Russian could hope from his fellow-countrymen was that they should regard him with good-natured pity. Nowadays, Marx’s ideas dominate the Russian revolutionary movement. Those Russian revolutionists who, in conformity with ancient custom, reject Marxism wholly or in part, have really long since ceased to be in the vanguard, and (though most of them continue to shout revolutionary slogans) they have, without being aware of it, entered the great camp of those who have been left behind.

Much nonsense has been written and repeated about Marx’s polemic methods, about the frequency and violence of his attacks upon his adversaries. Peaceful and rather stupid folk have explained these broils as the outcome of his uncontrollable passion for controversy, which, in its turn, was said to be dependent upon a malicious disposition. As a matter of fact, the almost unceasing literary campaigning in which he was engaged (especially during the earlier days of his socialist activity) was not an expression of his personal character but was due to the importance of defending his ideas. He was one of the first socialists to adopt the outlook of the class struggle, unreservedly, and as a matter of practice as well as of theory; and he was one of the first to draw a sharp distinction between the interests of the proletariat and those of the petty bourgeoisie. It is not surprising, therefore, that he came into frequent and violent clash with the champions of petty bourgeois socialism, who were very numerous in those days, especially among the members of the German intelligentsia. To refrain from arguing with these gentry would have been tantamount to abandoning the thought of consolidating the workers into a party of their own, with its special historical aims, and not tied to the tail of the petty bourgeoisie. “Our task,” wrote Marx in the “Neue Rheinische Zeitung” in April, 1850, “must be unsparing criticism, directed even more against our self-styled friends than against our declared enemies. Since this is our attitude, we shall gladly renounce the enjoyment of a cheap democratic popularity.” The declared enemies were not so very dangerous, for they could not obscure the class-consciousness of the proletarians; whereas the petty-bourgeois socialists, with their programs which professed to be “above class,” continued to lead many of the workers astray. A fight with these blind guides was inevitable, and Marx carried it on with his customary fervour and inimitable skill. We Russian social democrats must not fail to profit by his example, we who have to work under conditions very like those which prevailed in Germany prior to the revolution of 1848. We are surrounded by the petty-bourgeois apostles of a specifically “Russian socialism”; and we must never forget that the interest of the workers makes it incumbent upon us, too, to criticise our self-styled friends unsparingly (to criticise the social revolutionaries, for instance) — however disturbing this outspokenness may be to the well-meaning but foolish advocates of peace and harmony among the various groups of revolutionists.

Marx’s teaching is the modern “algebra of the revolution.” An understanding of it is essential to all who want to carry on an intelligent fight against the existing order of things. So true is this that many of the ideologues of the Russian bourgeoisie actually felt the need, at one time, of becoming Marxists. They found Marx’s ideas indispensable in their campaign against the antediluvian theories of the narodniks, theories which sharply conflicted with the new economic conditions in Russia. The younger bourgeois ideologues, being better acquainted than the others with contemporary sociological literature, realised this very clearly. They raised the Marxist banner, and, fighting under it, acquired considerable renown. But when the narodniks had been utterly routed, and when their antiquated theories lay in ruins, our new-made Marxists decided that Marxism had served their turn, and must now be subjected to stringent criticism. This criticism was undertaken on the pretext that sociological thought must not stand still; but its net upshot was that our sometime allies made a retreat into the positions occupied by the bourgeois social reformers of western Europe. How pitiful were the results of this loudly trumpeted “critical” campaign! How impracticable it was for the Russian social democrats to make common cause with these “critically” transformed people! At first, indeed, an attempt was made to join forces with them against the common enemy; the hope was entertained that an approximation of outlooks might be possible. But maturer consideration showed that this backsliding of our neo-Marxists into the camp of the bourgeois social reformers was not only the most natural thing in the world, but was also a signal confirmation of the truth of Marx’s materialist conception of history. In 1895 and 1896 the Marxist current in Russia swept away persons who had nothing in common with the proletariat, and no concern with the struggle for the emancipation of the workers — from whose cause they were fundamentally estranged both by their social position and by their mental and moral characteristics. At one time it was fashion to talk Marxism in the government offices of St. Petersburg. Had this continued, it would have been necessary to admit that the founders of scientific socialism were mistaken when they declared that people’s way of thinking depended upon their way of living, and that the upper classes cannot become the champions of the modern social revolution. But the “criticism of Marx” which began soon after the fight against the reactionary attempts of the narodniks had been fought to a successful issue, showed once more that Marx and Engels were right. The “critics” way of thinking was determined by their social position. In their revolt against the “fanaticism of dogma,” they were really revolting against the revolutionary content of Marxist teaching. The Marx they needed was not the Marx who throughout a life of toil and struggle and want had never ceased to cherish the sacred fire of hostility to capitalist exploitation. Marx as leader of the revolutionary proletariat appeared to them unseemly and “unscientific.” The only Marx they had any use for was the Marx who, in the Communist Manifesto, had declared his willingness to support the bourgeoisie in so far as this class showed itself revolutionary in the struggle against the absolute monarchy and the petty bourgeoisie. They were only interested in the democratic half of Marx’s social-democratic program. Nothing could be more natural than their attitude. But these perfectly natural developments show that there is no warrant for regarding such persons as socialists. Their place is among the forces of the liberal opposition, to which they have supplied (in the person of Mr. P. Struve, the editor of “Osvobozhdenie”) vim, talent, and literary skill.

The future was to show the truth of Marxist theory — and not in Russia alone. Every one knows that for a very long time western scientists ignored Marxism, which was regarded as the outcome of nothing better than revolutionary fanaticism. But in the course of time it became more and more obvious, even to persons who looked through bourgeois spectacles, that this product of revolutionary fanaticism had at least one great advantage — it provided an extraordinarily fruitful method for the study of sociology. With the advance of the scientific investigation of primitive culture, history, law, literature, and art, investigators in ever greater numbers found it necessary to adopt the theory of historical materialism: even though most of them had never heard of Marx and his theories; while those who had heard of Marx were very much afraid of his theories, which were materialistic, and therefore (to bourgeois eyes) immoral and a menace to social tranquility. Nevertheless we find that the materialist explanation is already acquiring a right of domicile in the learned world. Last year (1902) Edwin R. A. Seligman, an American professor of economics, published a book entitled Economic Interpretation of History. This is evidence that the priests of official science are becoming aware of the great scientific importance of the Marxist materialist conception of history. Seligman goes so far as to expound the causes which have hitherto prevented the adoption and understanding of this theory by the bourgeois scientific world. He says plainly and frankly that Marx’s socialist deductions have alarmed men of science; but he tells his scientific brethren that these socialist deductions can be jettisoned, for all that need be retained is the historical theory upon which they are based. This ingenious notion (which, let me remark in passing, was dearly though timidly set forth at an earlier date by Struve in his “Critical Remarks”), (3) gives one more proof that it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a bourgeois ideologue to reach a proletarian standpoint. Marx was a revolutionist to the fingertips. He was in revolt against God and capital, just as Prometheus was in revolt against Zeus. Like Prometheus, he could say of himself that his task was to educate persons who, knowing human sorrow and human joy, would have no respect for a deity hostile to human beings. But the bourgeois ideologues serve this deity. Their task is to defend his domain with spiritual weapons, while the police back them up with truncheons, and the soldiery with rifles and bayonets. The business of bourgeois scientists is to use those theories only which are not dangerous to God or to capital. In France and in other lands where French is spoken, men of science are much franker about this than they are elsewhere. For example, the famous writer Laveleye says that economic science must be thoroughly renovated, for it has ceased to fulfill its purpose since the days when the frivolous Basdat compromised the defence of the established order. Quite recently, A. Bochaud, in a book dealing with the French school of political economy, (4) appraised the various economic doctrines by an interesting standard. He asked, “Which of them will supply the most efficient weapons for combating socialism?” It is obvious, therefore, that bourgeois ideologues, when adopting Marxist notions, will do so “in a critical spirit.” The severity with which they “criticise” Marx gives the measure of the irreconcilability of the views of that dauntless and indefatigable revolutionist with the interests of the ruling class. It is likewise plain enough that a consistent bourgeois thinker will more readily accept Marx’s philosophy of history than Marx’s economic theory; for historical materialism is much less likely to do any harm than the doctrine of surplus value. This latter, to which one of the most vigorous among the bourgeois critics of Marx has given the expressive name of the theory of exploitation, is in bourgeois circles always described as “unfounded.” The cultural bourgeois of our day prefer the “subjective” economic theory, according to which economic phenomena have no connection whatever with the conditions of production — in which the exploitation of the proletariat by the bourgeoisie takes its source. To bourgeois economists, any allusion to such a matter seems particularly undesirable at the present time, when the class-consciousness of the workers is advancing with giant strides.

The economic, historical, and philosophical ideas of Marx are not acceptable in all their formidable completeness, and with their full revolutionary content, except by the ideologues of the proletariat, whose class interest is linked, not with the preservation but with the overthrow of the capitalist system — in a word, with the social revolution.

NOTES

1. Lessner writes: “Marx’s house was always open to trusty comrade.”

2. Mr. M. Tugan-Baranoffsky, sometime “Marxist” but now a bourgeois economist, in his “Sketches from the recent History of Political Economy” (p. 294), repeats the anarchist gossip about Marx having been a party to the dissemination of a printed slander on Bakunin. This is not the place for the examination of the evidence that is usually adduced in support of the story. I shall deal with the matter fully in “Zarye,” where the light-hearted assertion of Mr. Tugan-Baranoffsky will receive its proper valuation. But it is worth noting that our ex-“Marxist” did not trouble to examine his sources critically. He has simply repeated an accusation, which, being unsupported by any sort of proof, in its turn becomes a /‘slander.”

3. A Russian work published at St. Petersburg in 1894. The full title is “Critical Remarks on the Problem of the Economic Development of Russia.”

4. Les Ecoles economiques an XXme sibcle, 3 vols., Paris, 1902-1912.

Karl Marx: Man, Thinker, and Revolutionist; a Symposium edited by David Riazanov, Translations by Eden and Paul Cedar. International Publishers, New York. 1927.

Contents: Introduction by D. Ryazanoff, Karl Marx by Friedrich Engels, Engels’s Letter to Sorge concerning the Death of Marx, Speech by Engels at Marx’s Funeral, Karl Marx by Eleanor Marx, The June Days by Karl Marx, The Revolution of 1848 and the Proletariat A Speech by Karl Marx, Karl Marx by G. Plehanoff, Karl Marx and Metaphor by Franz Mehring, Stagnation and Progress of Marxism by Rosa Luxemburg, Marxism by Nikolai Lenin, Darwin and Marx by K. Timiryazeff, Personal Recollections of Karl Marx by Paul Lafargue, A Worker’s Memories of Karl Marx by Friedrich Lessner, Marx and the Children by Wilhelm Liebknecht, Sunday Outings on the Heath by Wilhelm Liebknecht, Hyndman on Marx by Nikolai Lenin, Karl Marx’s “Confessions” by D. Ryazanoff.

PDF of book: https://archive.org/download/in.ernet.dli.2015.54746/2015.54746.Karl-Marx-Man-Thinker-And-Revolutionist_text.pdf