Written in 1935 after end of the Communist Party’s own ‘dual union’ phase, this essay by William Z. Foster, formerly the leading syndicalist in the United States, traces syndicalism’s history here and gives his analysis of its conditions, characteristics, and failings.

‘Syndicalism in the United States’ by William Z. Foster from The Communist. Vol. 14 No. 11. November, 1935.

In its basic aspects, syndicalism, or more properly, anarcho-syndicalism, may be defined very briefly as that tendency in the labor movement to confine the revolutionary class struggle of the workers to the economic field, to practically ignore the state, and to reduce the whole fight of the working class to simply a question of trade union action. Its fighting organization is the trade union; its basic method of class warfare is the strike, with the general strike as the revolutionary weapon; and its revolutionary goal is the setting up of a trade union “state” to conduct industry and all other social activities. In short, syndicalism is pure and simple trade unionism, using militant tactics and dressed up in revolutionary phraseology.

In restricting the organization of the working class to the trade unions and in confining its struggle to the economic field, syndicalism commits a whole series of fatal mistakes. Among the most important of these are: (1) failure to provide the closely-knit organization of the most developed revolutionary elements (which must be a Communist Party.) indispensable for uniting and leading the less developed masses; (2) failure to utilize the many political methods of struggle vitally necessary to carry on the workers’ daily fight against the state and the capitalists for the eventual overthrow of capitalism, and for the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat; (3) failure to establish a basis for the unity of the workers with the poorer sections of the farmers and petty bourgeoisie against the capitalists, a unity fundamental for effective struggle against capitalism; (4) failure to work out a practical plan for the operation of the workers’ society after the abolition of capitalism.

Thus, briefly, by preventing the revolutionary political organization of the workers, by hindering their developing political struggle, by alienating their natural class allies, and by confusing them regarding the future order of society, syndicalism demobilizes the workers politically before the attacks of the capitalist state, and it leads inevitably to the defeat of the working class in its revolutionary struggle.

Let this very brief outline suffice to characterize the syndicalistic tendency. Although possessing certain specific characteristics of its own (which I shall discuss in passing) American syndicalism nevertheless basically conformed to the foregoing skeleton analysis of syndicalism in general. Here my task is not to analyze at length syndicalism theoretically as a movement, nor to demonstrate in detail its weaknesses. That has been thoroughly done already by others. The main question here is to trace the origins of syndicalism in the United States, to point out those objective and subjective factors that have produced this syndicalism, and to indicate, at least in a general way, the role it has played in the revolutionary movement of the United States.

I. THE EXTENT OF SYNDICALISM

Before tracing the major causes of American syndicalism, let me first briefly outline the extent to which this tendency has prevailed. Now syndicalism has developed more or less in nearly every country which has a substantial capitalism. But as a rule it has been much weaker in the more industrialized countries. The most outstanding exception in this respect, however, is the United States. In the United States syndicalist tendencies have been manifest to a far greater extent (manyfold in fact) than in the other highly industrialized countries, notably Great Britain and Germany. Indeed, it is not generally realized just how very extensive syndicalism has actually been in the United States, and what a great role it has played in the American revolutionary movement. Nor has the Communist Party yet paid sufficient attention to analyzing this important syndicalist tendency and its many consequences.

The reality is that for a full thirty-five years syndicalist tendencies, more or less clearly developed in the different periods, were very pronounced in our revolutionary movement. During all these years they kept sprouting here and there spontaneously, showing that syndicalism had powerful native roots in the objective situation. To secure at least an inkling of the great extent of this crippling tendency, let us glance back very briefly at some of the major features of our labor history, and then we will find syndicalism continually cropping out on a broad scale in the revolutionary movement.

Let us begin with the great eight-hour-day struggle of 1886. This historical movement already bore strong syndicalist features. Its acknowledged leaders, Parsons, Spies, etc., were anarcho-syndicalists rather than the anarchists which they have been called. They were anti-political; their organization was the trade union; and their major weapon was the general strike—all syndicalist characteristics. They had a huge mass following and were a decisive influence in the labor movement of the time.

In the nineties such important labor unions as Debs’ American Railway Union and De Leon’s Socialist Trades and Labor Alliance also bore distinct traces of a nascent syndicalism, with their superstress on economic struggle, industrial unionism and dual unionism and under-stress on political action. Furthermore, in this same period, De Leon, by gradually minimizing the role of the Party before, during and after the revolution, and by exaggerating the role of the trade unions, was developing the opinions that were eventually to lay the main theoretical foundations of American syndicalism.

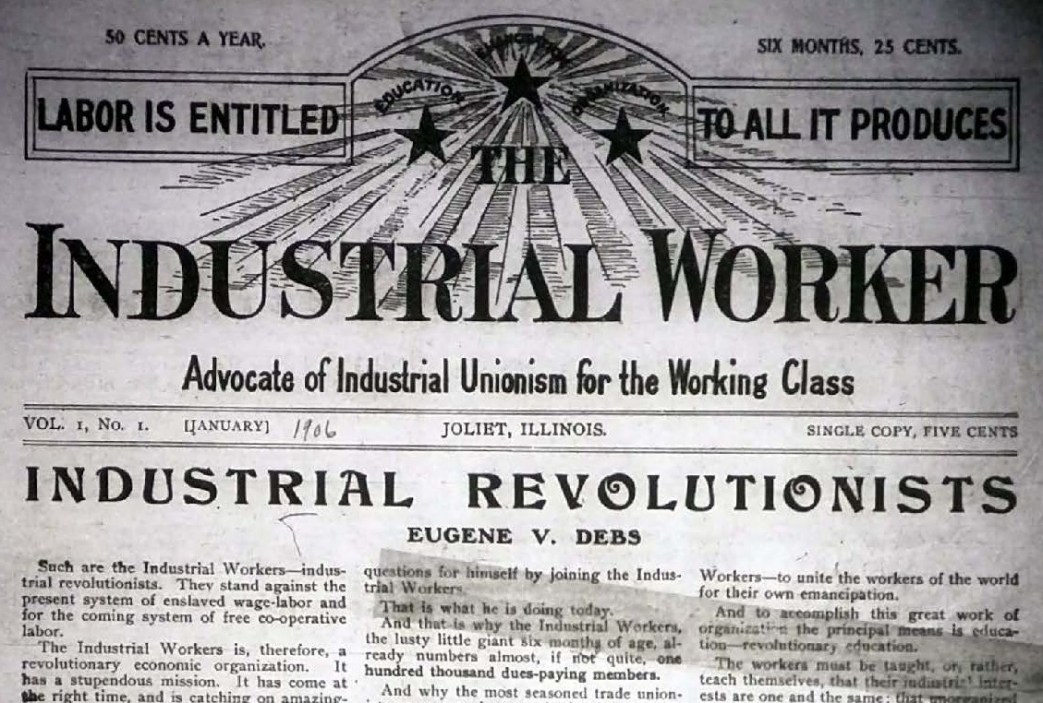

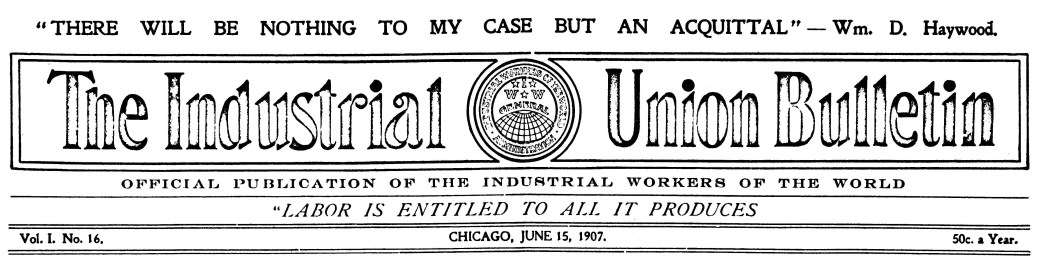

After the turn of the century syndicalist tendencies in the Left wing became even more pronounced and clear-cut. A number of industrial dual unions were formed during the period shortly after 1900 with decided syndicalistic trends, such as the United Railroad Workers, American Labor Union, etc. This trend came to a head in 1905 with the formation of the Industrial Workers of the World. At first but semi-syndicalistic, the Industrial Workers of the World soon developed its basic syndicalistic character and became the classic example of American syndicalism. It conducted many big strikes and for a dozen years was a real factor in the labor movement and even extended to several other countries. It especially exerted a profound influence over Left-wing elements in every organization.

In 1913 came the Syndicalist League of North America. This organization, although much smaller than the I.W.W., had considerable influence in the trade unions. It eventually gave rise to the Trade Union Educational League in 1920, which was also distinctly syndicalist at its formation. Shortly after the Syndicalist League of North America was launched, the Goldman anarchist group also tried to establish a syndicalist league, but nothing came of it.

More significant still of the strong syndicalist trend in the American revolutionary movement was the powerful and persistent syndicalist sentiment in the Left-wing of the Socialist Party. It is not too much to say that from the time such a Left-wing began to take shape in the Socialist Party, about 1902 or 1903, it was literally saturated with syndicalistic tendencies up till the split of 1919.

Characteristically, the three outstanding Left leaders of the two pre-war decades displayed strong syndicalist trends. De Leon, as we have already indicated, was actually the theoretical father of American syndicalism; Debs, although in lesser degree, shared many of his syndicalist illusions about the role of the trade unions, and Haywood became definitely a syndicalist.

It was the Socialist Labor Party and the Left-wing of the Socialist Party that were responsible for the formation of the syndicalistic I.W.W. in 1905. At that time the political conceptions of these Lefts were confused and their syndicalist trends strong. This is sufficiently illustrated by the fact that in the long manifestoes calling the first convention of the I.W.W. there is no mention whatever of the government, no more than if it did not exist, and the whole problem of the workers is posed solely as a problem of revolutionary trade unionism. This manifesto was signed by such diverse Socialist and other Left elements as Debs, Haywood, Trautmann, Mother Jones, A.M. Simons, Untermann, Shurtleff, Frank Bohn and Father Hagerty. And when the I.W.W. was formed, its famous political clause in the preamble (put in by De Leon and later removed by the “direct activists”) showed a distinctly syndicalistic trend inasmuch as while it called for organization in the political as well as the industrial field, it proposed as the revolutionary way for the workers to “take and hold that which they produce by their labor, through an economic organization of the working class without affiliation to any political party”.

Fundamentally, the Left-wing of the Socialist Party was political. It was that stream in the labor movement that gave birth to the Communist Party, the revolutionary Party of the working class. But that it was afflicted with a heavy admixture of syndicalist features is also evident from even a glance at its developing program after the launching of the I.W.W. In the 1909 fight in the Socialist Party of the State of Washington, for example, the Left-wing program was anti-parliamentary and otherwise syndicalistic. And when the disastrous split took place many of the Left-wing leaders, especially the proletarians, such as Joe Manley, Floyd Hyde and Joe Biscay, and others went over to the I.W.W. I, myself, did the same and remained a syndicalist for a dozen years.

The Socialist Party Left-wing in the big inner-Party fight of 1912, led by Bill Haywood and the International Socialist Review group, was even more syndicalistic and more under the influence of the I.W.W. ideology than in 1909. The bitter internal fight at that time centered around the question of the right of Socialist Party members to advocate sabotage, a central syndicalist policy. The Left-wing was defeated in this historic struggle. Haywood, the Left leader, thereupon quit the Party, became a professed syndicalist and thenceforth devoted his whole activity to the anti-political I.W.W. Large numbers of other Left-wingers followed his example and to a great extent the Socialist Party Left-wing movement liquidated itself into syndicalism.

In the Socialist Party split of 1919 which gave birth to the Communist Party, the Left-wing, although by then considerably more matured politically, was still afflicted by many of the characteristic syndicalist features of anti-parliamentarism, dual unionism and industrial union utopianism. But if this time the movement did not degenerate into syndicalism as in previous splits, it was because of the existence of new and strong influences, corrective of the traditional syndicalist sickness of the Left-wing and of which I shall speak further along.

To the foregoing more definitely syndicalist tendencies may be added the “economism” or sort of Right-wing syndicalist trend of the old trade unions themselves. ‘This conservative official American Federation of Labor syndicalism, brother under the skin to the more radical brand, was evidenced by the trade unions’ stubborn resistance for many years to extending their struggle on to the political field, by their long continued fight against an independent labor party, by their sharp opposition to all labor legislation regarding working hours, wages, social insurance and the like affecting adult workers,

II. FACTORS MAKING FOR SYNDICALISM

The foregoing brief references to American labor history, especially Left-wing history, suffice to show the existence of a widespread syndicalist tendency over many years. They also indicate that the United States developed a much stronger and deeper-rooted syndicalist movement than either England or Germany, which were comparable industrial countries. In Germany, the syndicalist movement, a narrow sect, never amounted to much, and England never had a native syndicalist movement; what little syndicalism it had being partly due to American I.W.W. and partly to French C.G.T. (1) influences. But the syndicalist tendency in the United States was native, deep-rooted and persistent through a long period of years.

What, then, was the reason for this strong development of syndicalism in the United States? It is a timely question; for up till now the question of our syndicalism has not been adequately analyzed and explained, and the remnants of this old-time syndicalism still exert some influence in the revolutionary movement.

Obviously the explanation of syndicalism in the Latin countries, France, Italy, Spain, etc.—on the ground that it derived from the less developed character of industry and the prevalence of strong anarchist traditions—does not apply to the United States. This country is a classic land of big industry and monopoly capitalism and it possesses but weak anarchist traditions. Hence the explanation for our heavy dose of syndicalism must be looked for elsewhere.

In my judgment, the basic causes of American syndicalism are to be found in a whole series of other economic, political and social factors, operating over a long period. These forces, by hindering the growth of class consciousness and checking the development of independent working class political organization and activity, tended to restrict the struggle of the workers to the economic field and thereby created the objective conditions favorable to the development of syndicalism. (2) Among the more important of these factors, merely indicated here, are the following:

1. Bourgeois democratic illusions. Inasmuch as the American bourgeois revolution accorded the workers a considerable degree of formal rights of free speech, free press, free assembly, the right to organize and strike and set up a fiction of legalized social equality, this situation resulted in a growth of bourgeois-democratic illusions among the workers and the latter, aware of no burning political immediate demands, were greatly hindered in developing independent class political organizations and action. What grievances the workers were conscious of loomed up to them as economic—such as questions of wages, hours, working conditions, etc. This is the most fundamental reason why there was no mass labor party or Socialist Party developed in the United States and why the workers have made their main fight on the economic field—the mass of workers had no platform of urgent political demands such as would be required as a basis for such a party. (3)

2. Flexibility of the two-party system. The decentralized character of the two old capitalist parties and the policy of the capitalists to make small concessions to the labor aristocracy enabled many of the more conservative trade unionists, especially officials, to be elected to government office on the basis of their “milk and water” labor program. This fact put a definite check upon the formation of a separate working class mass party.

3. No strongly centralized national government. Because of the highly developed “states rights” principle in government, the workers faced government oppression (troops, police, hostile court decisions, anti-labor legislature) mainly from the individual state governments (until recent years), and this tended to scatter the workers’ political struggle and to hinder the growth of a national mass labor party. Hence, American labor parties of a mass character have always been upon either a local, state or regional basis.

4. Government free land. The existence of free government land over several generations, down to about 1900, this land to be had by settlers upon easy conditions, has been often cited as one of the basic factors hindering the revolutionary development of the American working class. For many years it acted as a safety valve to leak off the discontent of the urban and agrarian toiling masses.

5. Higher living standards. The existence of higher wage standards generally in the United States than in the countries from whence millions of immigrants came was undoubtedly an important check upon working class discontent generally.

6. Large labor aristocracy. The United States for long had a relatively large aristocracy of skilled workers, principally American born. These, organized mainly in the American Federation of Labor and supporting the two capitalist parties, have been a great bar to American proletarian progress. Their ultra-reactionary leaders, corrupt to the core and shameless agents of the bourgeoisie, have for two generations ruthlessly used the great power of their organizations to defeat every attempt of the Left-wing to organize independent working class political organization and struggle or to propagate revolutionary ideas among the masses.

7. Bourgeois prosperity illusions. During the very rapid industrialization of the United States, large numbers of workers became well-to-do, many became petty bourgeois and some even big capitalists, This did much to blur class lines, to create bourgeois prosperity illusions among the toiling masses, and to check independent working class political development.

8. Disfranchised immigrant workers. During the whole period of rapid growth of American industry, about 50 years, there was present a large body of immigrant workers, in later years running into many millions. These immigrants, being largely non-citizens and very often not intending to remain long in the country, were more interested in economic questions of wages, etc., than in political matters. Hence, they as a mass were subject to non-political and often anti-political moods. Many of the Italians and other Latin groups had strong syndicalist traditions. And inasmuch as the revolutionary movement historically (S.L.P., S.P., I.W.W., C.P.), has always based itself largely, if not mostly, upon these foreign-born masses, it was unquestionably greatly influenced by their non-political attitudes.

9. Floating workers. Another force in the working class making against independent political action was the large body of itinerant workers in the West, several hundred thousand in number, made up chiefly of agricultural workers, construction workers, miners, lumbermen, etc. ‘These workers, mostly homeless, familyless, penniless, jobless, were a militantly revolutionary force. Although many were American-born, they were nearly all disfranchised and voteless because of residence disqualification; hence, in view of the general syndicalist trend of the Left-wing, they became virulently anti-political. Their great political significance lay in the fact that they early captured control of the I.W.W., gave it its pronounced syndicalist character and formed its backbone during its whole period of important struggle and influence.

10. Heterogeneous composition of the working class. Unquestionably the fact that the American working class has been for so long made up of such a great variety of nationalities, with different languages, standards of living, traditions, etc., constituted a difficulty in the way of organized working class action, especially political action, the employers and political bosses knowing well how to play off one group against another, especially the Americans against the foreign-born and the whites against the Negroes.

11. Corrupt American politics. For many years American workers have been disgusted and dissuaded from political action by the shameless corruption of American political life, marked by wholesale open bribery of representatives, brazen stealing of elections, etc. Even as early as 1886 we find Albert R. Parsons urging as a reason for boycotting politics the fact that a short while before, the workers in Chicago had been ruthlessly robbed in the counting of ballots in the city elections.

12. Petty-bourgeois control of the Socialist Party. Ever since its inception the Socialist Party has been controlled by radical petty bourgeois elements (doctors, lawyers, preachers, petty business men, etc.), who, feeling the pressure of trustified capital and seeing no hope in the two old parties, flocked into the Socialist Party to use it and its proletarian following in defense of the interests of the petty bourgeoisie. Their grip on the Socialist Party remains unbroken till this day. Consequently the proletarians in the Socialist Party were never able to use it as a revolutionary party. And this situation thus gave a powerful stimulus to syndicalism by closing another important gateway to working class political action and tending to confine Left-wing activities to the economic field.

Ill. THE DEVELOPMENT OF SYNDICALISM

The foregoing were the main factors, chiefly objective in character, making for the development of American syndicalism. They are the native soil in which this persistent deviation grew. Individually and collectively they tended, let me repeat, to check the general growth of class consciousness among the workers, to prevent the organization of a mass workers’ party and to hinder the development of sustained independent class political action of the workers. Their combined effort was basically responsible for the fact that historically the class battles of the American workers have been fought almost entirely on the economic field, in the realm of trade unionism.

But these objective factors, however strong, were not of themselves sufficiently powerful to have created the syndicalism of the S.L.P., S.P., I.W.W., S.L. of N.A., etc. Still another strong factor, subjective in character, entered decisively into the situation. This was the historical tendency of the Left-wing, instead of struggling against these anti-political forces, to adapt itself to them and to restrict its revolutionary struggle to the economic field. In this manner arose the stubborn syndicalist tendency which plagued and weakened the American revolutionary movement for so many years.

Instead of making a Marxian analysis of the many factors working against proletarian class political action and then laying out a sound program for their theoretical penetration, the Left-wing confusedly retreated before them and tended to develop its movement solely in the sphere that lay open before it, the economic field. It theorized an anti-parliamentarism conveniently to fit those factors making against political action and, under cover of many radical phrases and gross distortions of Marx, it reduced the role of the Party and it showed how the labor unions alone could overthrow capitalism and operate socialism in such a highly industrialized country as the United States. This syndicalistic adaptation was all the more facilitated because, although the American working class was so passive politically, it nevertheless militantly resisted on the economic field the ever-sharpening capitalist exploitation, and for fifty years before the World War it had a record of hard fought and bloody strikes such as no other country had, except tsarist Russia.

The United States, being a rich field for syndicalism, was also subject to a great deal of anarchist and syndicalist propaganda from foreign countries, especially France. It absorbed much of this, including anti-parliamentary theories, glorification of the general strike as the workers’ supreme revolutionary weapon, elevation of sabotage into a major proletarian tactic, theories of decentralization, spontaneity, etc. But the fundamental causes of American syndicalism were the native influences above-cited.

Thus our syndicalism, in the last analysis, must be traced to the theoretical weakness of the Left-wing in the United States. The revolutionary elements did not know how to develop a revolutionary political policy and party in the face of so many obstacles to mass working class political action. Instead, they tended constantly to yield before these difficulties and to take the easiest theoretical road into the syndicalist swamp.

It was the great strength of the Russian Communist Party that it had as its leader the masterful Marxian theoretician, Lenin. Over many years Lenin was able to penetrate and fully expose the fallacies of liberalism, “economism”, syndicalism, menshevism, populism, anarchism, Trotskyism, and many other dangerous anti-proletarian trends. And thus the Russian workers were able, under the most adverse circumstances, to develop a revolutionary political program and to build around it a solid revolutionary party. It is safe to say that without this tremendous preliminary theoretical work by Lenin the Russian revolution could not have succeeded.

But the American revolutionary movement had no Lenin. Nor was it, until the Russian Revolution, even aware of his writings. It had indeed very few real contacts with the Left-wing in other countries, and the opportunistic petty-bourgeois Socialist Party leaders, who, of course, had every reason to prevent the development of a revolutionary political program, were careful to keep the Left-wing thus isolated. Although possessing the works of Marx and Engels as general guides, the American Left-wing proved theoretically incapable of the great task of analysis and organization confronting it, in the special problems of developing capitalism in the United States and thus it failed to build a real Bolshevik Party, however small it might have been. On the contrary, it floundered about theoretically for many years on the edge or in the midst of the syndicalist mire. And its best leaders, over a period of thirty years—De Leon, Debs, Haywood—could do not better than help it lose itself in the syndicalist swamp. (4)

The theoretical history of the Left-wing of the American revolutionary movement contains many syndicalist and semi-syndicalist illusions piled upon each other. Space limitations forbid a detailed recital of all these errors. Suffice it to briefly indicate here three of major character, all operating simultaneously, each one of which opened up a broad avenue to syndicalism.

1. Underestimation of the role of the Party. Instead of realizing that the Workers’ Party was the main fighting leading organ of the proletariat, there was a persistent tendency to minimize its role, an error that led straight to syndicalism. The “Left” sectarian Socialist, De Leon, was a big sinner in this respect. By abandoning all immediate political demands and by considering the labor unions as the principal fighting organization of the working class, he reduced the Party to the weak status of a mere propaganda organ and practically an auxiliary of the labor unions. This opened the door wide theoretically for the syndicalist deviation. Debs was much affected by De Leon’s semi-syndicalistic minimizing of the role of the Party and exaggerating that of the unions. As for Haywood, he liquidated the role of the Party altogether, and further degraded De Leon’s feeble parliamentarism into a virulent anti-parliamentarism and put all his trust in the unions as the leading revolutionary organs of the working class. And the masses of the Left-wing in the S.L.P., S.P., and I.W.W., pressed as they were by so many objective factors hostile to working class political action, naturally enough followed these syndicalistic vagaries of the outstanding leaders.

2. Dual unionism. The Left-wing in the S.L.P., S.P. and I.W.W. never understood the role of the conservative trade unions. It could not perceive their working class character beneath their veneer of bourgeois ideology and reactionary leadership, and the necessity for rebels to penetrate and revolutionize them. On the contrary, De Leon, Debs and Haywood, who so well expressed the thought of the American revolutionary movement, vied with one another in finding phrases sharp enough in condemnation of the reformist unions as capitalist organizations and in setting up rival revolutionary unions against them. This policy of dual unionism, followed with the greatest intensity for twenty-five years by the Leftwing, was a fruitful source of syndicalism. It detached the Left-wing from the organized masses and reduced its movement to a sectarian basis. It thus facilitated the development of the great overestimation of the importance of the industrial form of labor union, the ascribing to this structure an almost magic strength, and the giving leash to that remarkable “one big union”, wheel-of-fortune union-diagram and chart-making utopianism which was such a characteristic feature of American syndicalism.

3. Misconception of the role of the state. The capitalist state is the strong right arm of the capitalist class, its principal means for violently subjecting and exploiting the working class; and the capitalist class can never be expropriated until the workers and their class allies, by force of arms, smash that state. These are elementary truths, fundamental for the workers’ struggle, and they were many years ago established by Karl Marx. But our Left wing long failed to grasp their significance, for it was infected throughout its history with many semi or syndicalistic theories of defeating the capitalist state and overthrowing the capitalist system merely by economic strikes: that is, by “locking out the bosses”, or by the workers en masse simply folding their arms and refusing to work. De Leon contributed much to such theories, which reached their full logical development in the I.W.W. and its supporters in the Left wing of the S.P., and which were fatal to the development of revolutionary political struggle and the Party.

The Left wing also long had a totally wrong conception of the future proletarian state, of the dictatorship of the proletariat in the period of transition to Socialism after capitalism should be overthrown. This was shown by its syndicalist conceptions (prevalent for many years in the S.L.P., S.P. and I.W.W.) of the future society being operated in all its phases by the system of industrial unions.

The syndicalist errors in the prevalent Left-wing conceptions of these three major questions of the Party, the unions, and the State, are evident at a glance. They were of sufficient importance to put a syndicalist or semi-syndicalist stamp on the whole Left-wing movement and to undermine its political work. And a whole series of other syndicalist conceptions, which were also present, might be added to the foregoing. The extent to which such syndicalist conceptions prevailed in the S.P., S.L.P. and I.W.W. over so many years was the measure of theoretical failure of our revolutionary leaders to break through all the objective obstacles I have pointed out earlier, and to develop a revolutionary political program and organization, even though it were but a small Party.

IV. THE DECAY OF SYNDICALISM

Although the syndicalist tendency persisted so long and vigorously in the American revolutionary movement, it has finally shrunk to a very minor factor. Its decline dates from the Russian revolution and was chiefly caused by that great event. This is because, in the fire of the practical experience of this first great Socialist revolution, these fundamental lessons of revolutionary working class program, organization and strategy, were made to stand forth so clearly that many previous false notions on these vital questions were exposed as manifestly fallacious and harmful. The Left wing in this country was able to learn the major political lessons thus so dramatically taught, and in consequence its syndicalism began to vanish.

The experience of the Russian revolution (combined with the after-War struggles generally in Europe) thoroughly exposed the bankruptcy of syndicalism (as well as of revisionist socialism and of anarchism ). In blazing letters of fire it pointed out the only way to proletarian revolution. Among other great revolutionary truths, it made as clear as day the role of the workers’ party (which must be the Communist Party) as the militant leader of the revolution and the supreme thinking, fighting organ of the working class before, during, and after the revolution. It showed inevitably that without such a party there could be no proletarian revolution. It exposed he folly and disaster of the syndicalist plan of attempting to substitute the mass trade unions for the Party of trained revolutionaries, and of the plan to depend upon spontaneity for united action. It demonstrated in practice the role of the trade unions in the pre-revolutionary period, in the revolution itself, and during the era of socialist construction, and it fatally showed up the incorrectness of the syndicalist position on all these points. It exploded the syndicalist nonsense of overthrowing the capitalist state by a “folded arms” general strike, and proved by practice as well as by theory that not by a narrow economic trade union strike, but only by a broad armed uprising of the working class and its farmer allies can the toilers abolish the capitalist system. And, finally, it gave a practical demonstration of the structure and operation of the revolutionary workers’ state—the dictatorship of the proletariat, and showed the futility of the syndicalist notions of the mass trade unions operating the industries and generally conducting socialist society.

For workers with eyes to see and ears to hear, the meaning of all these great lessons spread to the toilers of the world through the writings of Lenin, is plain—the syndicalist path is not the way of revolution but a surrender to the bourgeoisie. And the American revolutionary movement mostly had such receptive eyes and ears, and it did learn.

Under the influence of the Russian revolution and the great lessons it taught, the Left wing of the Socialist Party, headed by C.E. Ruthenberg, and already long in revolt against the reactionary Right-wing Socialist Party leaders, began to shed its traditional syndicalist illusions and to adopt a truly revolutionary political policy, a Communist program. That is why when the S.P. split took place in 1919, the Left wing did not liquidate itself into the syndicalist swamp as it had done several times before in struggles against the Right-wing leaders.

The organization of the Communist Party was a death blow to American syndicalism. The Communist Party’s policy of Leninism was a magnet that soon attracted the best revolutionary elements of all labor organizations. The Left wing of the I.W.W., led by Haywood, affiliated itself to the Communist Party and the I.W.W. soon shriveled into a small, reactionary sect. The best elements of the S.L.P. also joined the Communist Party. The members of the Syndicalist League also joined the Communist Party, as did the Fox proletarian group of anarchists. Weakened in all these Left strongholds of the S.P., I.W.W., S.L.P., and S.L. of N.A., etc., syndicalism passed swiftly into decay.

It would be a mistake, however, to conclude that, although American syndicalism was dealt such a fatal blow by the Russian revolution, it was liquidated immediately offhand. On the contrary, syndicalist remnants of anti-parliamentarism and dual unionism lingered in the Communist Party, and there are traces of them there yet. These syndicalist vestiges have caused much ideological and organizational weakness in the Party (their prevalence had considerably to do with the severe factional fight from 1923-29), and the Party, under the guidance of the Communist International, has labored sedulously to eliminate them.

Besides this liquidation of the subjective syndicalist factor by the Russian revolution, the traditional American objective factors that made difficult organized political action by the workers and that created the fertile soil for syndicalism have also been greatly modified in recent years, especially since the onset of the present great world economic crisis. Thus (to mention these factors in the order I have presented them above), (1) the workers have now become strongly conscious of a whole set of major political demands during the present crisis (unemployment insurance, 30-hour week, government work, national minimum wages, against fascism and war, etc., etc.), which provide a solid political basis, the first time in American history, for a mass labor party; (2) the Federal government has become vastly more centralized, especially in the past three years; (3) the effects of the former free land have, of course, by now practically disappeared; (4) the traditionally higher American wage and living standards have gone to smash in the crisis, and the masses are full of discontent; (5) unemployment, wage cuts, mechanization of industry have greatly undermined the privileged position of the labor aristocracy and weakened its reactionary influence among the toiling masses; (6) the old-time and dangerous bourgeois prosperity illusions are fast going also in the crisis, and masses of workers, however waveringly, but with the Soviet Union in their minds, are beginning to think in terms of revolution; (7, 8, 9) the working class is rapidly being made more homogeneous by mass unemployment, weakening of the labor aristocracy, stoppage of immigration and maturing of the immigrants’ children, etc.; (10) the revolutionary workers now have a fighting Communist Party of their own that is fast gaining a mass following and whose struggles for the united front are increasingly gaining the support of the Socialist Party membership and the trade unionists. This favorable shift in both the subjective and objective factors that once made for syndicalism greatly favors the development of revolutionary political organization and struggle by the workers. It should be no surprise, therefore, that the rising wave of proletarian struggle in the United States takes on increasingly a political character. Syndicalism, although traces of it still linger, as a living mass tendency among American workers, is dead.

The Communist International and Red International of Labor Unions have conferred many benefits upon the American revolutionary movement, but none greater than the elimination of the erroneous syndicalistic theories that had so long crippled it. By linking up the American Communist Party with the great Russian Party and with the fighting Communist Parties and labor unions of Germany, China, etc., and by greatly raising our Party’s theoretical level, by giving our Party generally the benefit of the experience of the world revolutionary movement, the Comintern and Red International of Labor Unions have helped our Party to mature, that is, to accomplish the theoretical tasks it could not do alone, to develop a revolutionary American political program and Party, to set its feet firmly on the Marxian-Leninist path, and to lay the foundation for a revolutionary struggle that is now gradually mobilizing the starving, toiling masses and that will one day put “finish” to bankrupt American capitalism and establish a Soviet America.

NOTES

1. Confederation Generale de Travail (General Confederation of Labor).

2. Marx and Engels long ago noted this tendency for the American masses are now ready for a broad labor party.

3. I have dealt with this subject fully in a recent article in The Communist International entitled “The New Political Basis for a Labor Party in the United States” (No. 12), showing how, by the growth of mass political demands, the masses are now ready for a broad labor party.

4. I need hardly again say that I, myself, to the extent that I had any influence, also helped to create the syndicalist confusion.

There are a number of journals with this name in the history of the movement. This ‘Communist’ was the main theoretical journal of the Communist Party from 1927 until 1944. Its origins lie with the folding of The Liberator, Soviet Russia Pictorial, and Labor Herald together into Workers Monthly as the new unified Communist Party’s official cultural and discussion magazine in November, 1924. Workers Monthly became The Communist in March ,1927 and was also published monthly. The Communist contains the most thorough archive of the Communist Party’s positions and thinking during its run. The New Masses became the main cultural vehicle for the CP and the Communist, though it began with with more vibrancy and discussion, became increasingly an organ of Comintern and CP program. Over its run the tagline went from “A Theoretical Magazine for the Discussion of Revolutionary Problems” to “A Magazine of the Theory and Practice of Marxism-Leninism” to “A Marxist Magazine Devoted to Advancement of Democratic Thought and Action.” The aesthetic of the journal also changed dramatically over its years. Editors included Earl Browder, Alex Bittelman, Max Bedacht, and Bertram D. Wolfe.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v14n11-nov-1935-communist.pdf