‘The Story of Hawaiian Sugar’ by Marion Wright from The International Socialist Review. Vol. 16 No. 1. July, 1915.

HAD it not been for her sugar Hawaii might have still been free, ruled by her own Queen and people. But sugar is money, and sugar forced the island Empire into the arms of Uncle Sam and turned her over to the tender mercies of the missionary and sugar planter. The story of the growth of the sugar industry in Hawaii is akin to an Arabian Night’s tale. A kingdom has been overthrown; difficulties have been met; obstacles overcome; methods changed, and results achieved that would have been unthinkable fifty years ago.

The sugar planters of Hawaii managed to make sugar enough for home consumption and to export 277 tons in 1856, approximately the daily output of a few mills in 1906. In 1910 the sugar output was 517,000 tons, nearly two thousand times as much as that of only fifty years ago.

The sugar mills of 1856 consisted of little wooden rollers standing on end, operated by bullocks and fed by hand, one stick at a time. Their exact duplicates are still in use in the Philippines. Iron, three-roller mills had just begun to be introduced and they weighed less than a ton apiece. The best mills of the islands in 1914 use twelve-roll mills with a cutter and crusher to first reduce the cane to shape.

Sixteen and a half tons is the weight of the large mill rollers, in addition to which 430 tons of hydraulic pressure is applied to the rollers to assist in pressing the juice from the cane. The mills of 1856 extracted less than half of the sugar from the cane. All the mills of the present give an extraction of over 90 per cent and some run as high as 95.

The sugar planter of 1856 plowed but little, used no fertilizer, knew practically nothing of irrigation, boiled his sugar in a scrap iron pot bought from a whale ship and was even then “short of labor.”

Over two hundred thousand immigrant laborers have been brought to Hawaii by sugar. The supply is still short and the problem is becoming not only vexing to the Hawaiian exploiters but to the government at Washington. Sugar will release no less than 60,000 Japanese of voting age in Honolulu in a few months and there is talk of placing the islands under the government of a military committee to bar these yellow votes.

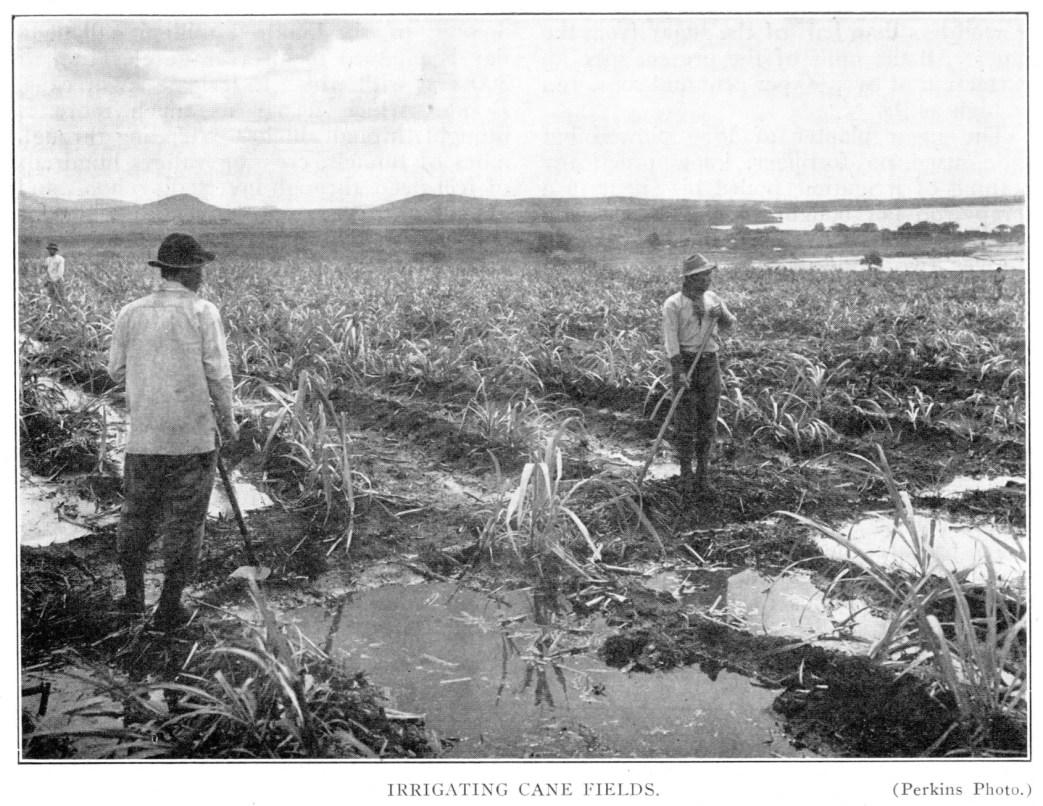

To prepare the sugar land, twenty-ton steam plows break up the soil; five to fifteen hundred pounds of fertilizer, costing $40 a ton, are applied annually to each acre of cane under cultivation. Water to the amount of six hundred million gallons a day is pumped to an average elevation of 200 feet with which to irrigate sugar cane. Besides which nearly as much more is brought through ditches extending through miles of tunnels, crossing valleys hundreds of feet deep, through inverted syphons, and extending to forty miles in length, while the whaler’s scrap tub for making sugar has been exchanged for apparatus costing from half a million to a million to each mill.

The average yield per acre in 1856 was one ton of sugar. The average yield ten years ago was four and one-half tons, while individual irrigation plantations averaged ten tons per acre.

In 1856 the sugar planter received ten cents per pound for his sugar and lost money. The planter of today gets five cents and makes money. The story of the Hawaiian sugar industry interweaves with the political, social and religious history of the islands. It touches kings and revolutions, fabulous fortunes forced from the soil and the workers and total losses of immense wealth in a few short years. Plantations have paid sixty dollars dividends a ton one year and lost twenty dollars a ton the next. As late as 1905 a plantation which figured very conservatively to produce 20,000 tons made but 1,600. The cause was “leaf hopper” and drought, and to many others disaster has come along with success.

When cane first came to Hawaii or how it was brought is unknown. Captain Cook found it upon discovery of the islands and in later voyages spoke of it as being a common article of food and supply to shipping. In 1823 an Italian made sugar in Honolulu by pounding the sugar cane with stone beaters, on poi boards, and boiling the juice in small copper kettles. In 1841 the governor of Hawaii planted about 100 acres of cane, having it farmed by Chinamen.

The Civil War in the United States gave the first great impetus to the Hawaiian sugar industry. The war immediately cut off the supply of sugar from the southern states and raised prices generally, resulting in a rapid increase in the output from Hawaii, the exports being 1,283 tons in 1861 and 8,869 tons in 1868. A sugar refinery was established in Honolulu in 1861. It confined its operations to boiling over and refining molasses from the mills.

The rapid extension of the business created such a demand for labor that the wages of field laborers rose to a dollar a day, an unprecedented thing at that time, including free rent, wood, and medical attendance. The earth was scoured in all directions for laborers, resulting in Hawaii securing the greatest mixture of races the world has even seen.

From five to fifteen hundred pounds of fertilizer are now used per acre on practically all the cane land of Hawaii, on virgin soil as well as old lands. The fertilizers used are chiefly compounded in Honolulu, where there are two large factories, and in San Francisco.

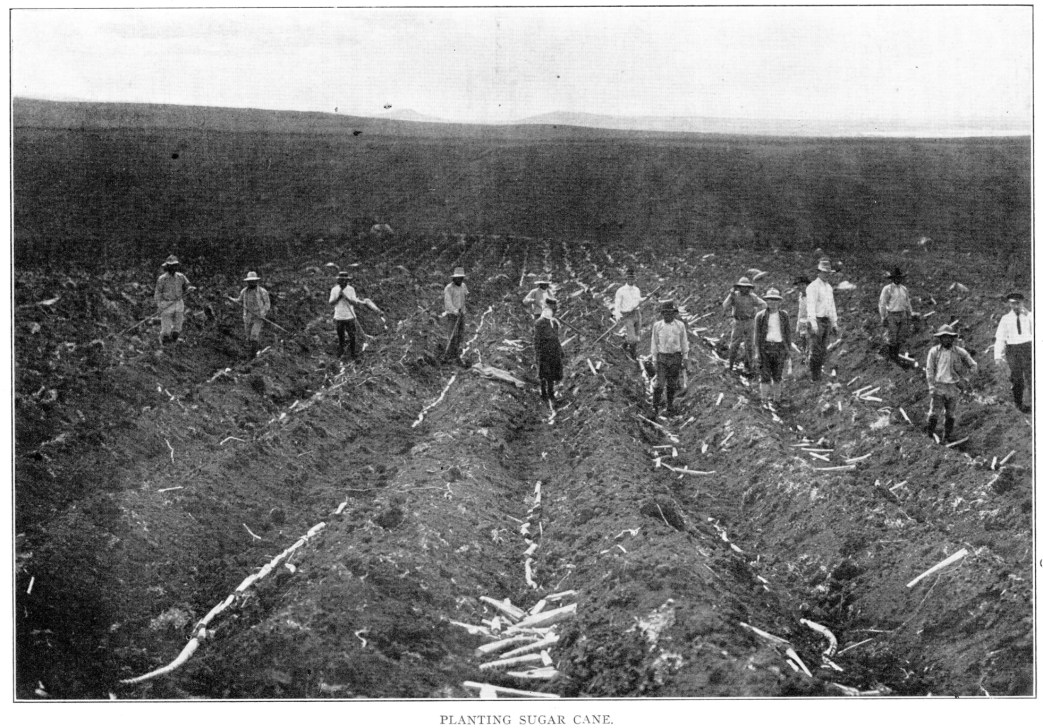

The methods of cultivation vary greatly in the different districts. Wherever there is deep soil, free of stock and not too hilly, steam plows are used, which break up the soil to the depth of thirty inches. Where irrigation is practiced the cane is planted in deep furrows. In unirrigated fields the cane is planted in shallow furrows running straight across the field regardless of grade.

On irrigated fields there is no cultivating with small plows or cultivators as these would break up the ditches. All weeding is done by hand. On unirrigated plantations the first weeding is done by hand and as soon as the cane is well started cultivators operated by one mule are used. Much greater care is given to thoroughness of plowing and to keeping the field clear of weeds than was formerly done.

The revolution in sugar machinery in fifty years is complete. Even the past ten years has worked most radical changes. The best mill buildings are now of skeleton steel structural iron, with corrugated galvanized roof and sides, and mostly iron or concrete floors. In front of the mills is a cutter and crusher for the purpose of flattening and preparing the cane so that it will be properly taken by the rollers. By reason of the high percentage of juice extraction the stalk is left so dry that it is carried direct from the rolls on an endless chain and automatically fed to the furnaces, which are specially constructed to burn this fuel. On the plantations which grind day and night these crushed stalks, or “bagasse,” furnish practically all the fuel.

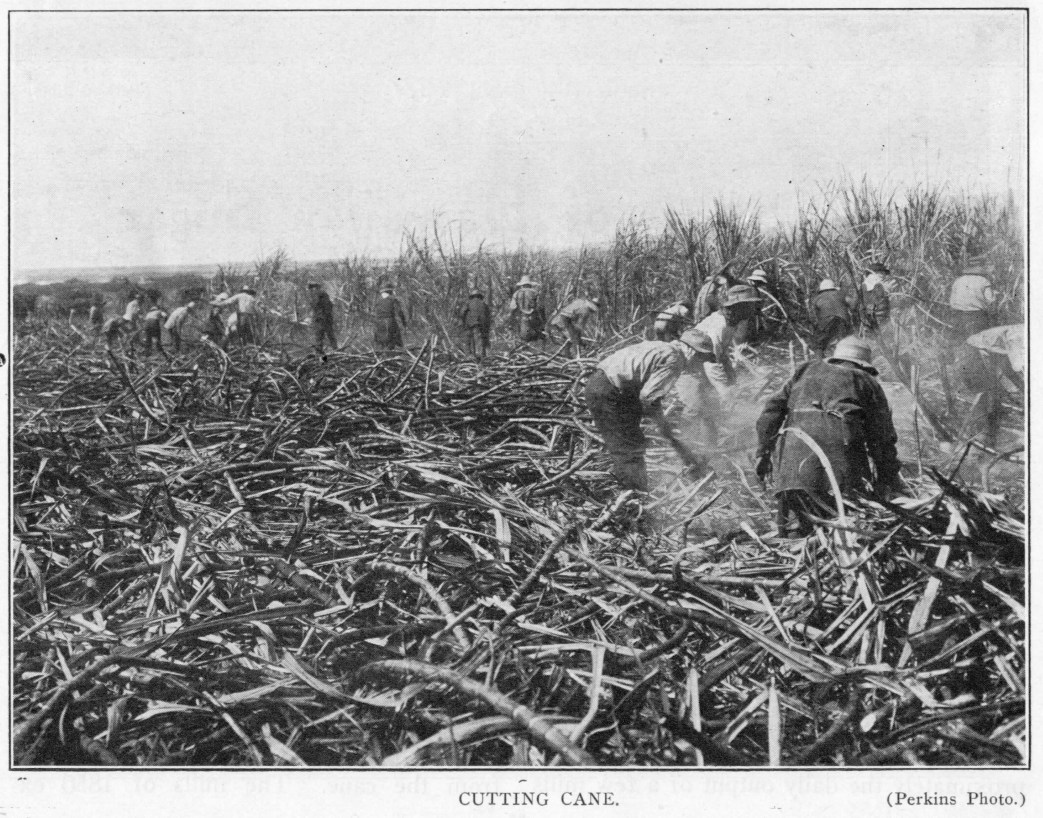

On nearly all the plantations waste molasses is now fed to stock and used as a fuel being sprayed on the “bagasse” in the furnace. It will probably be utilized in the near future to make alcohol. Labor-saving devices are the constant study of the Hawaiian planter. On some plantations machines load the cane onto the cars and unload it onto the cane carrier. Mechanical carriers take the cane to the mill, the bagasse to the furnace, and collect sugar from the centrifugals. Mechanical stokers feed the furnaces; elevators and hoppers bag the sugar and machines are being introduced which top and sew the filled bags. The one great labor devourer is harvesting the crop. From 500 to 800 men are required daily to harvest cane for one first class mill.

There is one point which baffles the growers of sugar cane and that is to increase the percentage of sugar. There has been practically no increase in the sucrose content of sugar cane since the plant was first known. This is due to the fact that it is propagated by cuttings and therefore offers no opportunity of improving the stock. Experiment stations are now working to produce fertile cane seeds so that the best varieties may be interbred and developed. Twenty years ago it was generally conceded that sugar cane would not produce a fertile seed. That great wizard of the fields, Luther Burbank, has stated that in his opinion the continuous and intelligent cross-fertilization and selection of sugar cane seed would double the percentage of sugar in cane within twelve to fifteen years. The present average output of sugar per acre in Hawaii is four and one-half tons.

If the same land could be made to produce nine tons the possibilities and profits of the sugar industry are almost beyond the limits of the imagination.

The one cloud upon the horizon of the sugar planter is the labor situation. The demand has never been supplied though higher wages are paid than in any other tropical country. This runs $20 to $30 a month for 26 days, ten hours a day.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v16n01-jul-1915-ISR-riaz-ocr.pdf