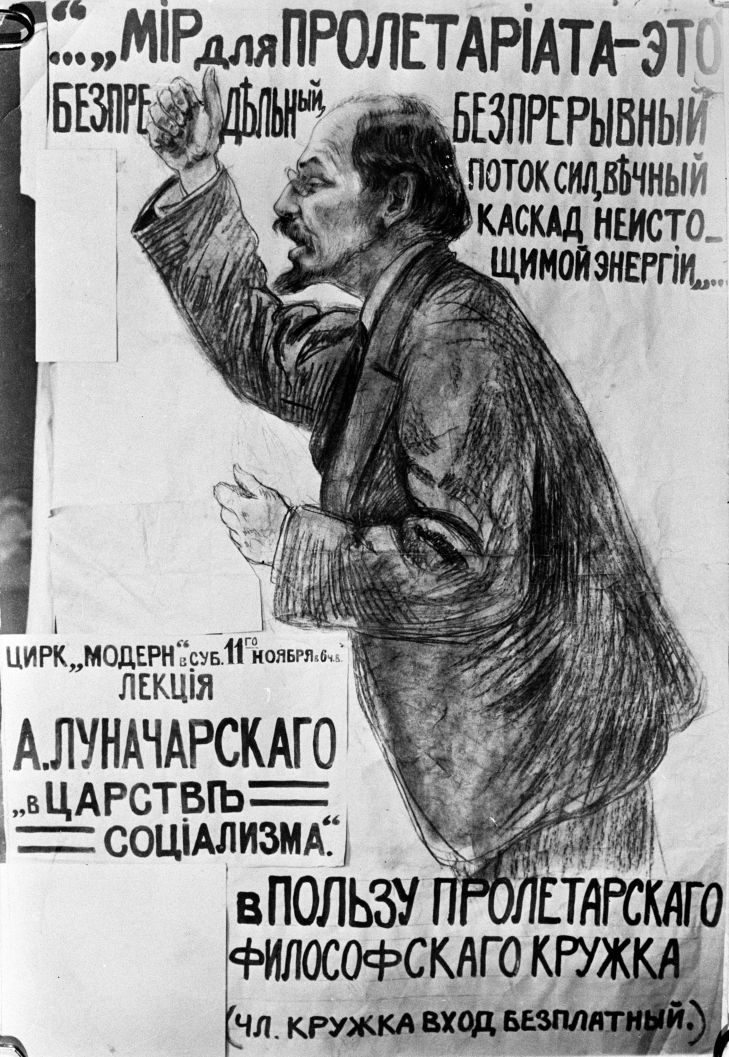

Wonderfully detailed and historically valuable report of the conference presided over by People’s Commissar of Public Education Anatoly Luncharsky held in December, 1920. Covering the work of the conference; Soviet reform of public education; policies towards the arts, music, theater, museums, libraries; the struggle for literacy; adult and workers’ education; language and national work; and political education.

‘First Conference of Soviet Educators’ from Soviet Russia (New York). Vol. 4 No. 12. March 19, 1921.

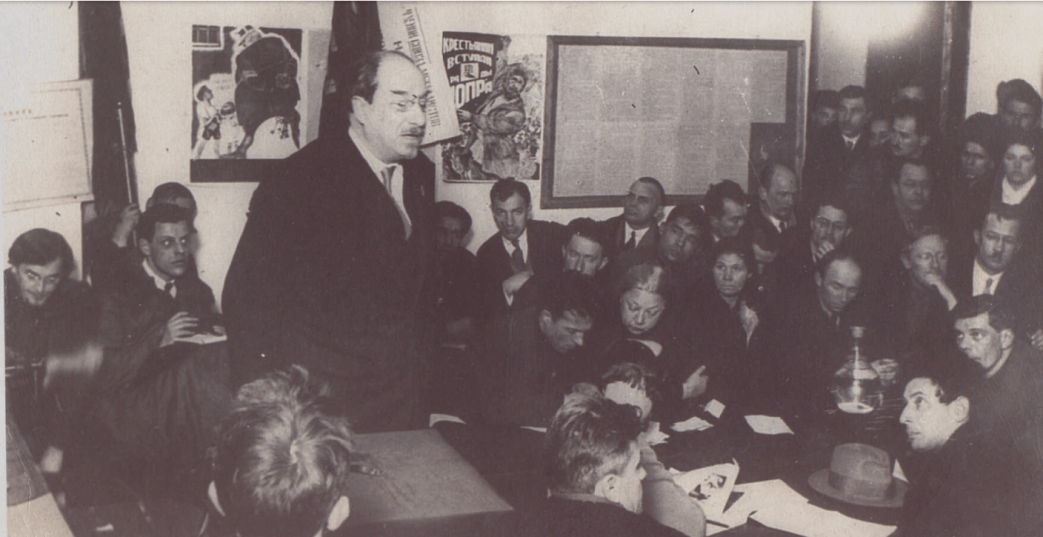

Delegates to Educational Congress: THE party Conference on public education which was called by the Central Committee of the arty opened on December 31, at 5 P. M. The decisions of the conference will have a vast importance for the whole organization of education in the Soviet Republic; the material and principles advanced await final decision at the Tenth Congress of the Party. The Conference likewise had to examine the question of the impending reconstruction of the organs of the Educational Commissariat, in conformity with the new tasks that are put before it as a consequence of the fact that the Soviet Government’s work is mainly concentrated on economic construction.

Every one who is prominent in educational work, together with representatives of the National Trade Union Council, the League of Youth, delegates from the Eigth Soviet Congress, and directors of the provincial departments of public education took part in the Conference. Representatives came from Petrograd, the Commissariat for Education of the Ukraine, the Khirgiz Soviet Republic, Azerbaijan, etc. The number of participants was 134 comrades with decisive votes, and 29 with advisory capacity.

First Day

The Conference was opened by Comrade Lunacharsky, who, in a few words, outlined a number of problems and the importance of the work to be done. The agenda being announced, the following committee was proposed: Comrade Zinoviev (Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party), Lunacharsky (R.S.F.S.R.), Kozelov (National Trade Union Council), Grinko (Ukrainian Education Commissariat), and Lilina (Petrograd Education Department).

Then Comrade Luncharsky, People’s Commissar for Education, in an introductory report, indicated the perspectives of the Commissariat for Education and the series of problems which have been put before it in the sphere of child-training and polytechnical education.

“The Commissariat for Education”—said Comrade Luncharsky- “is first of all the laboratory for the production and organization of a system of conviction, the basis, as Comrade Lenin said, upon which rests the coercion of the proletarian dictatorship. The Commissariat for Education is an organ of the Party. On the other hand it must carry out the orders of all the economic commissariats, training cadres of specialized and able men for all fields of industry. And in that sense it is an economic commissariat.

“Whereas the Party has hitherto concentrated all propaganda and agitation in the Party organs, it is now putting this work on the Soviet organs; i.e. on the organs of the Commissariat for Education. The Commissariat, similarly, is destined to unite the training of men scattered in various departments and organizations, as well as to establish scientific discipline.

“The maximum program of Communist education, put forward at the same time as the program of the social revolution, could not be realized, mainly because of the undeveloped status of the schools, the hostility and ignorance of the tutors, and still more, because in war time the Republic could not supply sufficient means for the work of public education out of its attenuated resources. That is why the facts are so far from the ideals contained in our declaration. Nevertheless, the Commissariat for Education still remains true to its first declaration concerning the uniform school, although perhaps with some modification in details. The pedagogic idea of Communism—-political education—remains the same even in relation to the transition period.”

Comrade Lunacharsky further defined the relationship between the system of social training for children and adolescents, which embraces them on the age-scale classification up to 15 years, in the form of the 7 years’ schools, after which they are sent for 4 years to the technical high school for special education. Thus, we have the education system as a network of institutions, first of all the pre-scholastic then the 7 years’ school and the 4 years’ technical high school for various specialties.

Having further spoken in detail of these, his basic postulates, Comrade Lunacharsky dwelt on the idea of industrial and agricultural schools, closely bound up with production and primarily for the youth of the working class; he then drew the attention of the Conference to one question of tremendous importance—the formation of a pedagogic personnel, and defined the measures outlined in this sphere, as for instance, the recruiting to pedagogic work of men from the technical and agricultural high schools, to train workers and peasants for elementary pedagogic work in short-term courses.

Second Day

The second day of the Conference began with Comrade Lunacharsky’s report on social training. Referring to the problem of family and school he said:

“The family is disintegrating with tremendous rapidity. On the other hand, I doubt whether there is a family at the present time that could afford any sound training for the children; not only our principles but want itself urges us in the direction of social training. In no case, however, can we adopt the principle of compulsion or persuasion.”

Examining in the latter part of his speech the charsky states that the approximate number of children being cared for (up to 400,000) is most insignificant in comparison with the vast mass of children that are in need of the attention of the State. Indicating the immediate perspectives as far as the growth of social training is concerned, the speaker Îaid it down that it is the basic task of the Commissariat for Education to further the work of building and perfecting schools.

“We should,” said the speaker, “realize a higher type of school, a club school, a whole-day school; that is, a boarding-school. The schools and the children’a homes are coming together, and with the development of our work we may look more calmly npon the fading of the bad influence of the modern family upon the children.”

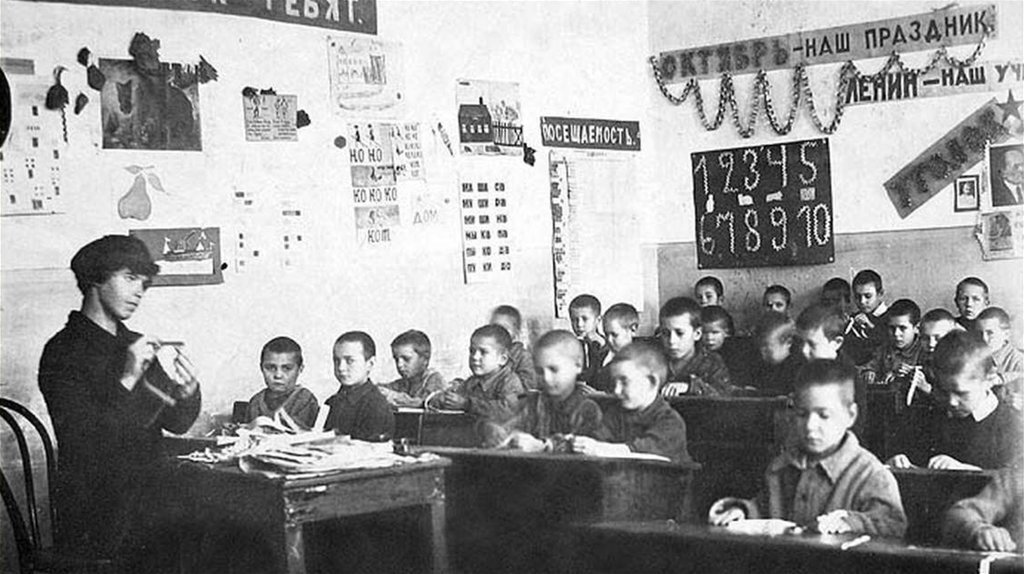

The Conference then attentively listened to the report of Comrade Litkens, concerning tuition reform. Comrade Litkens advanced postulates concerning the necessity of doing away with the method of instruction by means of lifeless routine, of ceasing to give the pupil abstract knowledge instead of the necessary abilities and habits on the basis of industrial labor processes. Comrade Litkens pointed ont the necessity, agogically, to adopt finally the forms of school life that would give the child a first training, so thst when it reached, let us say the age of 15 years, it could choose for itself a definite profession or speciality in the technical schools.

EDUCATIONAL REFORM (An Interview with Lunacharsky)

The reform of the Commissariat for Education is not at all confined to the appointment of new men and the concentration of the structure of the former Public Education Department. It is incomparably wider.

The basic functions of the Commissariat Education have been defined as follows: theoretical, administrative, and financial-supply. The theoretical work of the Commissariat has a special academic center, which draws up principles, works out plans and programs of a scientific and artistic character, administering purely learned and academic-art institutions and using them for pedagogic state purposes; all this is closely connected with the administrative center.

The organizing center concentrates all the work of financing, supply, and information, working in closest contact with the administrative center.

Finally the administrative center actually conducts both the model institutions under the direct management of the Commissariat, and the entire mass of educational institutions through the provincial educational departments.

The administrative center, in its turn, is split up into three head managing departments on the basis of the different functions of the Commissariat of Education. These are, the Chief Committee of Public Education, which carries on all the educational work among the children under 15 years of age; the Department of Vocational Education, which manages the work of preparing all kinds of workers for the State and for industry, embracing all the ages above 15 in the educational sphere; and the Political Education Department, engaged in general educational work (specifically Communistic) among the adult mass of the population.

Having created a sufficiently strong leading Communist nucleus to take the lead, it is proposed to recruit the collaboration of the best experts on a much wider scale and with more determination than has been done hitherto.

I consider it likewise of great importance to create councils at all the more important centers in which representatives of the Party, of the National Central Executive and the economic commissariats would take part. Such an institution existed some time ago in the shape of the State Committee for Public Education but it was whirled away in the general stream of disorganization that prevailed at that time. At present this institution, in the form of councils working systematically and evenly, is being revived. The desire of the All Russian Central Council of Trade Unions to combine the amalgamations of the labor unions in the center and in the provinces with the Commissariat for Education, fills me with the greatest joy. It certainly promises to infuse much freshness into the work and to facilitate the solution of the principal problem, which is, to bind the school stably with the population, and first of all with the workers.

ART IN SOVIET RUSSIA (From the Report of the Commissariat of Education)

In Tsarist Russia the enjoyment of art in all its forms was exclusively the privilege of the ruling classes. The “nation” only got wretched crumbs as a substitute. Knowing what a powerful means of agitation the theatre is for the masses, the police State kept a vigilant eye upon the so-called people’s theatres, fencing them round with a censorship, and entirely subjecting them to the police authorities. Education, both musical, theatrical, and artistic, was quite inaccessible to the masses.

It became the aim of the Soviet Government to make art accessible to all, to bind it up in the life of the laboring masses, to put it on a new foundation, so that it should draw new forces from among the proletariat.

At the same time, while working persistently towards the creation of a new, purely proletarian art, we endeavored to familiarize the proletariat with the best achievements of former art.

At the start, in the realization of this task, we met with our principal difficulty, which was the lack of talented forces in the art world, who could understand the tasks confronting Soviet Russian art, and could see them carried out. Only recently have we been able to make progress among the art workers and they have given us a number of prominent men, and helped us to put art on a sound basis.

The Theatrical World.

Much has been done in democratizing the theatre. The repertoire of the biggest theatres has been greatly improved; in this connection, we are still working to acquaint the workers with the best models of the classic theatre. By a recent regulation a uniform price for seats at all theatres has been established; this measure is a step towards the complete abolition of all pay for theatrical shows. Considering the theatre as an instrument of education and propaganda, we should make it free of charge, as we do the school. Parallel with the classical repertoire, there is slowly coming up a new revolutionary repertoire, which we are endeavoring to foster by means of competition in the studios and workshops.

On the other hand, among the working masses themselves, such a tremendous striving towards theatrical creation is evident that it has proved extraordinarily difficult to manage and direct all the theatres and groups that sprang up so naturally.

The Musical World.

In the musical field our path was generally the same as in the theatrical sphere, i.e., we aimed at drawing the wide labor masses to appreciate works of genuine musical art; extensive musical education was given and wide facilities for the production of new music, growing out of the proletariat itself and corresponding to the spirit of the times.

We are accomplishing the first task by creating a number of State orchestras, from our best orchestral forces. The Musical Department has formed five large symphony orchestras, about fifty small orchestras, and two orchestras of national instruments. These orchestras during 1919 and the beginning of 1920, gave in the provinces about 170 symphonic concerts from chosen works of classical music, 70 concert-meetings and over 170 concerts of various kinds. These concerts enjoy invariable success among the workers and Red Army men.

The work in the field of musical education is conducted along two lines; the musical education of the wide masses is attained by the establishment of a network of national musical schools, whose number at the present time is 75 (before the Revolution there was one); on the other hand the Musical Department of the Commissariat of Education is working extensively in the schools and children’s homes. Thus in Petrograd up to 500 schools and 600 children’s homes have included in their curricula the systematic teaching of music. Choir singing has been introduced in 80 per cent of all! the schools; the practice of music in 60 per cent; the nurseries all have a musical staff attached to them.

The second line is the creation of professional music schools, the number of which is already 200, with an attendance of 26,000. The percentage of worker and peasant students in the national schools is 70 per cent, in the vocational schools of the First and Second grades about 55 per cent, and in the higher musical schools it is not more than 30 per cent, which is naturally to be explained by the fact that a corresponding cadre of workers and peasants has not yet been prepared for the high schools.

Apart from this the Musical Department is engaged in the production of musical instruments; it is at present giving most attention to the revival of the noblest of Russian national instruments,— the “Dombra.” The nationalization of instruments and of music enabled the Musical Department to adopt measures for the correct distribution of this stock, and to take stock of especially valuable old instruments, of which a collection has been formed Thus we possess the only collection of the famous Stradivarius violins in the whole world; these are not hidden in the museums, but are given, on competition, to the use of the best violinists, who are obliged to let the masses hear good execution on the famous instruments.

The problem of realizing a new proletarian music is, of course, not going to be decided by means of decrees or by personal effort. In this regard our hope is with the proletarian youth who are training in our musical schools, and every spark of talent is supported by us by all possible means.

Fine Arts Department.

This department carries on extensive work of practical nature. Having made the industrial principle the basis of its work, it has spread a wide network of workshops, both of a purely artistic type and of industrial art where on the one hand it strives in general to develop the artistic taste of the working masses, and awaken talent amongst them, and on the other hand directly introduces the principles of art and style in industrial work. With the latter aim, work-shops have been set up for chintz work, wood-work, stonework, printing, pottery, and toy-making, etc. There are 35 such workshops in different parts of Russia. The total number of people in these workshops is 7,000.

Besides this the Department is organizing, both in Moscow and in the provinces, art exhibitions whose aim it is to acquaint the workers with all the tendencies of art in general. That fine art is not declining with us is proved clearly not only by the productivity, but by the quality of the work in our porcelain factories, whose productions are highly valued abroad. They now employ widely the watchwords and emblems of the times in their work. The State has given full freedom of development to all tendencies in the sphere of art, for it believes that its ever-growing contact with the working masses serves as the surest regulator for putting art on a firm and true foundation. The occasionally apparent preponderance of one tendency in art over another finds its explanation in the fact that energy and impetus is at times displayed by young art groups, which discover enthusiastically new ways or achievements. We regard this calmly and without apprehension. We are sure that the new artist, the proletarian-artist who has graduated from our art schools, will at the proper moment deliberately sweep away all that is superfluous and superficial; he will use all that is valuable, and will give to the world an art that will be unequalled for its vividness and expressiveness.

Museum Department.

One of the most brilliant pages in our art work is the activity of the Commissariat for Education in the sphere of the safeguarding of the monuments of art and of the past.

Since the Revolution, our museum collections have been growing all the time. All the treasures that had been hidden from the eyes of the masses in palaces and manors have been collected and placed in the museums, being the property of all the workers. The network of museums in the provinces is growing with unusual rapidity. From 31 at the beginning of the Revolution their number is now 119, and practically every day brings news of the opening of a new museum. The treasures of the Hermitage have grown by half as much again. The museums of the capitals have been rearranged, redistributed, and supplied with experienced guides, who read lectures and conduct the excursions of workers and peasants. Visits to the museums have grown numerically, and have changed still more qualitatively; workers and peasants are overfilling the museums. The attendance at the museums, especially in the provinces, is hard to define. It is sufficient, however, to point out that according to a rough report, the museums of Moscow alone, during 1919, had over 200,000 visitors. A number of country manors have been wholly transformed into museums, which vividly illustrate the life and surroundings in the Ducal Estates of the XVIIE and XIX centuries. Not less intensive is the work of restoration. The cleansing of ancient ikons has enriched our collection of very valuable productions of Russian ikon painting.

In spite of all the obstacles and difficulties, the Museum Department of the Educational Commissariat, slowly but splendidly, is working to restore the Kremlin and the Yaroslav Mosques.

Finally, archeological excavation has not ceased for a moment, and the study of our past is making good headway. Archeological groups of amateurs are being formed in the provinces, carrying on excavation and research under the guidance of scientific leaders.

OUT OF SCHOOL EDUCATION

From the very first day of its existence the Commissariat for Public Education was confronted by the problem of out-of-school education, or, according to the present terminology, of political-educational work.

We have to deal with a country in which the percentage of illiterates is enormous, a country which it was the policy of the Tsarist regime to keep in darkness and ignorance, a country which was in the power of most fanatical prejudices. The old Out-of-School Department, now the Political-Educational Department of the Commissariat of Public Education, faced the problem of organizing public libraries, schools of all types for adults, clubs, people’s houses, excursions, etc. The task was to — this activity and give it a communist direction. In the field of library work the results were the following:

In 32 provinces there were 13,500 libraries in 1919. In 32 provinces there were 26,278 libraries in 1920.

The number of libraries taken over by the Soviet Government was 11,904; of these there were 8,229 school libraries. In 1919, the number of libraries amounted to 25,562; the number of school libraries being 11,467. It should be pointed out that these figures are in no way sufficient to show the growth of the libraries, because they do not include a great number of establishments of the library type, which have grown up in the Red Army, nor the libraries organized by the trade unions for their members, nor the small libraries of a primary type, which serve as a basis for the so-called reading hots, the number of which amounts to about 40,000 on the whole territory of Soviet Russia.

Very characteristic are the figures showing the growth of the library matter in Petrograd:

Before the Revolution there were 23 libraries with 140,000 volumes; after the Revolution 59 libraries with 865,000 volumes.

After the Revolution 59 libraries with 865,000 volumes.

Further, the Out-of-School Department was engaged with the work of organizing schools of different types for adults.

In 1919, there were registered by the Out-of-School Department 7,134 schools for adults and 101 people’s universities.

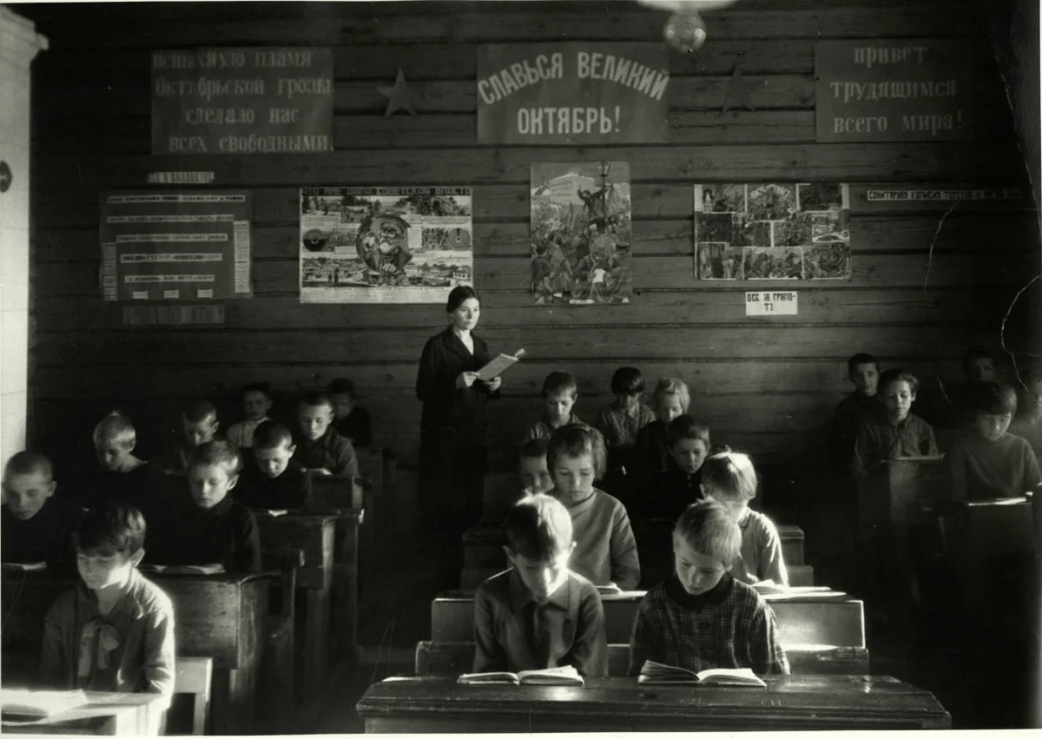

A special task was the work of liquidating illiteracy. By a decree of the Council of People’s Commissars an Extraordinary Commission for the Eradication of Illiteracy was created.

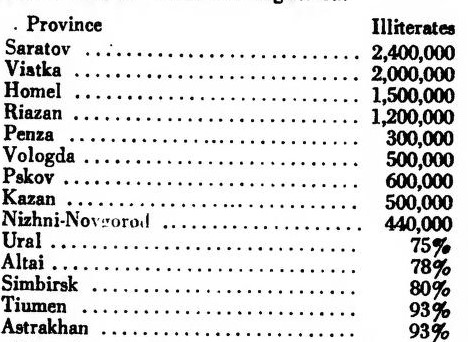

Here are some figures on the number of illiterates in Russia. There were registered:

These figures are eloquent of the difficulties and — scale of the work to be carried out in this field.

According to the plans of the Central Commission, courses are organized all over Russia for the preparation of a staff of teachers for the eradication of illiteracy.

In the province of Cherepoviets three-days county course-conferences were held, which were attended by 350 school workers; then two-days volost course conferences, which were attended by 10,000 persons, and finally, special instructors’ control courses, which were attended by 5,000 persons. Information was received about the organization of courses in the provinces of Archangelsk, Astrakhan, Vitebsk, Vologda, Viatka, Homel, Ekaterinburg, Kaluga, Kursk, Ivanovo-Vosnessensk, Moscow, Novgorod, Orel, Olonets, Orenburg, Penza, Samara, Saratov, North-Dvina, Simbirsk, Uralsk, Ufa, Cheliabinsk, Tiumen. (This information is for the period up to the middle of the summer 1920.)

The work of the Commission has given good results. The pace at which the work is being carried on is shown by the following figures:

During three months the liquidation courses were attended:

In the province of Tambov by 40,000 people; In the province of Cherepoviets by 57,807 people; In the province of Ivanovo-Vosnessensk by 50,000 people. In Petrograd by 25,000 people.

All over the Republic an enormous number of literacy schools have been opened; 10,000 schools were opened by the middle of Spring in the province of Cherepoviets alone; in the province of Tambov—6,000 schools, which were attended by 48,000 pupils m the month of April; in the province of Simbirsk—6,000 schools, in the province of Kazan—5,000 schools, which were attended by 150,000 pupils; in the province of Viatka 4,000 persons were attending the literacy schools, even before the decree was issued.

The information received from different cities furnish the following picture: In Petrograd there are 500 school establishments with 1 or 2 schools in each; 4,000 persons have already passed these schools, and 25,000 more are attending them at present. A great number of schools were opened in Moscow with 22,000 attending. There are 25 schools in Kronstadt, 190 schools in Kaluga, 150 in Tula, 130 in Kosmodemiansk, 65 in UrievePolsk, 45 in Kustanay, 40 in Gzhatsk, 20 in Zhisdrinsk, 20 in Romen, 300 in Berdiansk, 180 in Archangelsk, 190 in Omsk, 70 in Yelaguba, 30 in New-Omsk, 12 in Cheliabinsk, 15 in Ekaterinodar, 20 in Odessa.

It is interesting to point out the compulsory measures, which are practiced in different parts of the Republic: In the province of Kazan, those who refuse to attend the literacy schools are subject to 5,000 roubles fine, to 3 months of compulsory labor and the loss of their food cards. In Petrograd those who refuse to attend the schools are reduced to a lower food category, they are tried in a people’s court and excluded from the trade union. In the province of Tambov a signature for an illiterate has no validity.

Primers are printed in Russian, Polish, German, Tartar, Yiddish, and in the other languages of the peoples living in Russia, and a great number of copies are published.

According to our information, 2,700,000 citizens attended the schools during 1920.

But in order to carry out all this work, it was necessary to have a staff of Out-of-School education workers, of whom there were very few in Russia.

The Political-Educational Department developed its work in this direction, and by the end of 1919 a staff of 6,200 workers had been prepared. The number of courses was 65.

In order to complete the picture of the work carried out by the Department for out-of-school education, it is necessary to add the network of people’s houses and clubs, which is continually increasing, covering the whole country, and the enormous number of lectures, concerts, meetings and debates which are held daily over the whole territory of the Republic.

—Russian Press Review, No. 19.

Soviet Russia began in the summer of 1919, published by the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia and replaced The Weekly Bulletin of the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia. In lieu of an Embassy the Russian Soviet Government Bureau was the official voice of the Soviets in the US. Soviet Russia was published as the official organ of the RSGB until February 1922 when Soviet Russia became to the official organ of The Friends of Soviet Russia, becoming Soviet Russia Pictorial in 1923. There is no better US-published source for information on the Soviet state at this time, and includes official statements, articles by prominent Bolsheviks, data on the Soviet economy, weekly reports on the wars for survival the Soviets were engaged in, as well as efforts to in the US to lift the blockade and begin trade with the emerging Soviet Union.

PDF of full issue: (large file): https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/srp/v4-5-soviet-russia%20Jan-Dec%201921.pdf