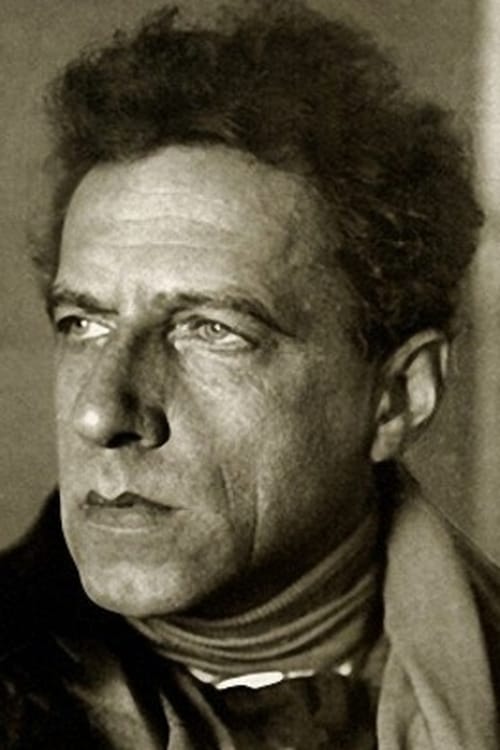

One of the great teachers of theater, the ‘father of method acting,’ and unforgettable star of Godfather II, Lee Strasberg was a key player in the radical theater movement of the 1930s. A perfect author to introduce the towering international figure of that movement, the great Russian director Vsevolod Meyerhold, as he does in this wonderful article from 1934. Moscow’s pioneering Meyerhold Theatre was closed by order of the Politburo in January, 1938. Vsevolod Meyerhold was arrested in 1939, and executed as a ‘British and Japanese spy’ and Trotskyist on February 2, 1940.

‘The Magic of Meyerhold’ by Lee Strasberg from New Theatre. Vol. 1 No. 8. September, 1934.

THE name of Meyerhold has long been of unusual significance. To the theatrical Russian it has been a rallying-cry or a danger signal. People still tell you of the actual fist fights in the streets about this man. To the foreigner with the added burden of the language difficulty, unaware of where to seek for the “why” or “wherefore” of what he sees before him, this is still a constant puzzle.

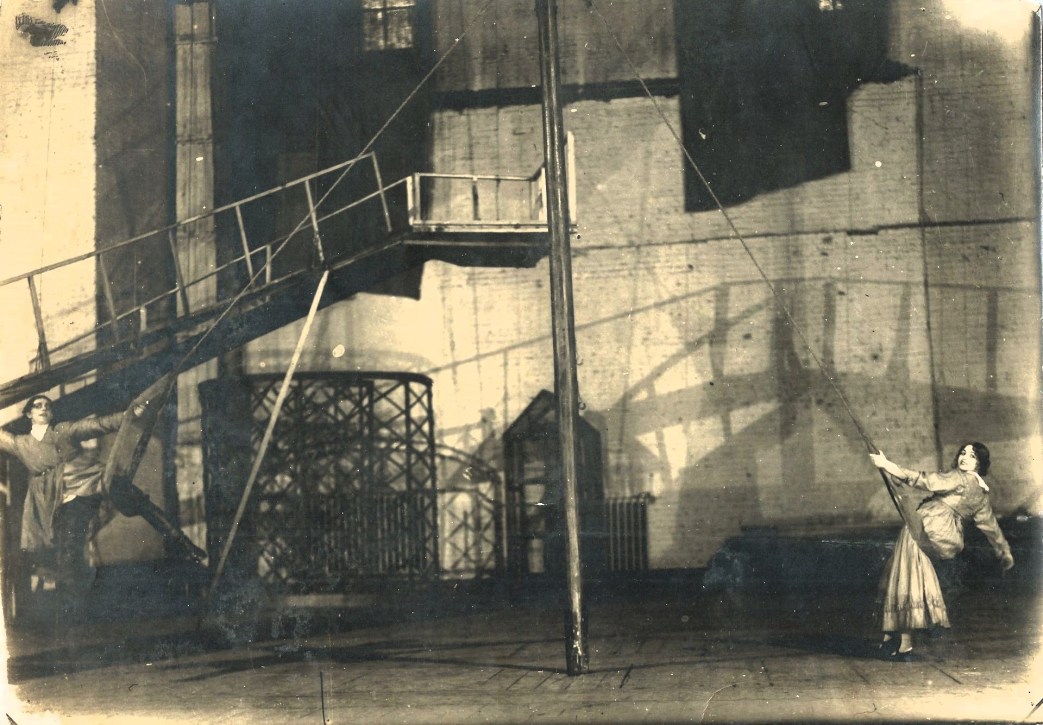

One sits in the Meyerhold Theatre awaiting the start of The Forest. There is no curtain. The scenery stares back at you, a bridge, a see-saw, a pair of swings. You do not know whether to smile or to be impressed. The audience babbles on quite unconcerned by now. A gong. The lights go out. On the stage the last props are brought on, candles are lighted; positions are taken. A gong. The lights go on. The play is on.

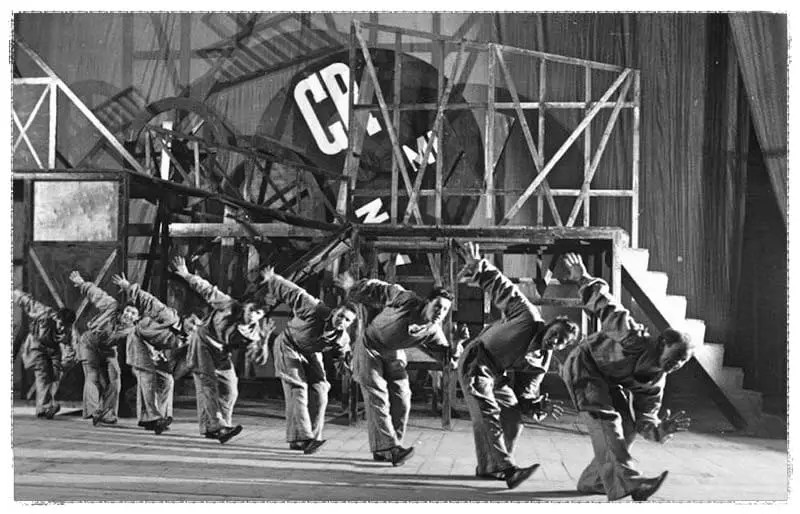

As you don’t know the language, you watch the scenery, the acting. You are annoyed and shocked by the latter. It looks old-fashioned. The actors move too much and posture and strut. You are sure you don’t like it. It is all so unreal. You feel out of it. You don’t know whether to be disappointed. It is certainly “different” and “unusual”. But is this the man of whom Vakhtangov said, “He is a genius. Every production creates an epoch in the theatre”? The play goes on however and before long you are thinking differently. You are caught by the scenic action, by its imaginativeness, by its flair. The entire life of the people begins to unfold. You feel you have misunderstood the scenery. It is not unreal. It actually makes possible more reality than would be possible in a realistic set. It stems from the desire not to be limited by the stage-the conventional set. Thus Meyerhold in The Forest can have the girl ironing, hanging clothes, chasing pigeons, people on a road, fishing, love scenes on the road…marvelous in its effect of throb and pulse- the large swings used for the first love scene, the action on the see-saw, all these following one another or intertwining one with the other, creating the entire atmosphere of the life on the old Russian farmstead, bringing out and sharpening the drama. The taps of the rolling pin, used to wring water from freshly washed clothes, serves to accentuate a quarrel, becomes the dynamic rhythm of the scene. The see-saw becomes an instrument to bring out a Freudian comment. In the first love scene, a simple text involving two minor characters, the actors climb into the swings. They swing higher.

“The spurts of hope are designated by Peter’s three upward flights, punctuated by the words, One day in Kazan, the other in Samara, and the third in Saratov! With every swing he goes higher…The swing of the upflight exactly conveys the movement of the intonation; the higher the tone, the steeper the upward flight.”

The young people in love swing up, as they fight to rise from their environment, and your own blood, as you watch, leaps with them. The girl stands on the bridge. The boy swings towards her. The mood is very lyric. The text is very simple. When you go back and study it, it is hard to realize it was not written to be played this way. But none of this would be possible in a confined, conventional, “cottage” set. The canvas of the production is elastic. It is a room or the whole Russian countryside. And sometimes it is both together; two men walk along a road toward the house, far away, the internal and related life of which is visible to us.

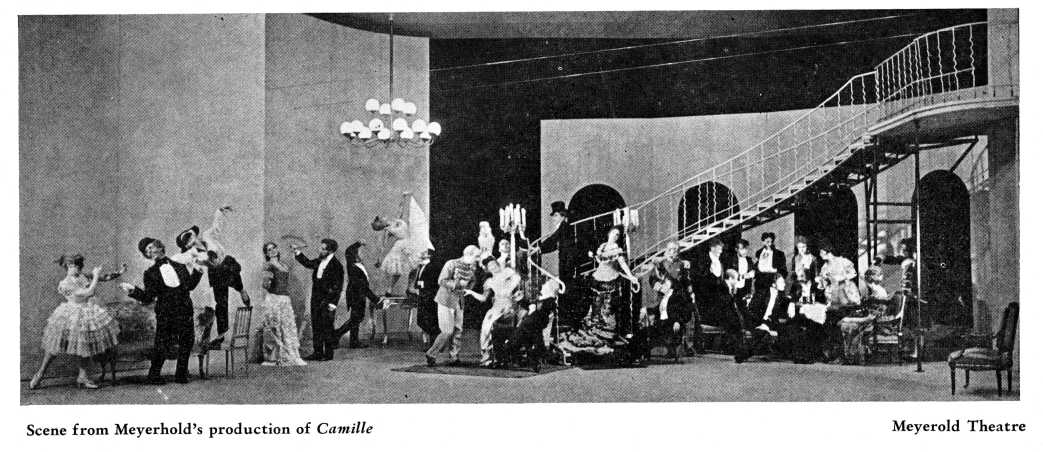

IF it is Camille you are watching, you are first dazzled by the amazing luxury of the sets and costumes. Each object is carefully arranged in its place in a magnificent composition, the whole breathing the very spirit of French art. And into this scene Camille blazes, literally stunning us by the cold theatricality of her entrance. Blindfolded, her body poured into a dress the soft red velvet of which accentuates her body, she drives before her two fatuous gentlemen harnessed like circus zebras. Her hands are covered with black gloves: one of them holds the reins, the other a scarlet whip with which she slashes at her two male steeds.

By the time the second scene comes on, we have been whirled into a maelstrom of movement and action. The scene in which Armande meets Camille is, from some slight hints in the text, turned into a party at her house. The whole life of the period swirls here. From one part of the stage to another, weaving increasingly in a steady beat, the songs, the dances, the poetic declamations, masquerading, move. Confetti and gay balloons appear out of nowhere. The whole becomes a riotous carnival mounting at terrific pace throughout the scene, creating a strange foreboding in its hecticness, an exhilaration, a desperate gaiety.

And yet throughout this entire episode the director’s magic succeeds in constantly riveting our attention on the almost motionless figures of Armande and of Camille, whose eyes behind her fan constantly search and flirt with him.

There are memorable touches in this scene. One comes at the moment in which Camille is prevailed on to sing. Her voice rises childish and strange, hardly in tune, wavering and hesitant as the notes picked out on the piano by a child. And at the end of the song, the actress collapses.

Again, there is the suggestive and grisly introduction of a mask of death, coming sharply on the encl of a love passage. It is noteworthy that this element, bizarre as it is, has been marvelously prepared for us by the introduction of two men in simple masks, and by the act of one of the characters in the play who, left without a partner for the dance, picks up one of these masks, fastens it to his cane and dances with it. Already, then, the masks have become symbolic, and when the friends of Camille enter in a procession with masks, we accept that one which represents death as a foreboding of doom. Thus the first act is a complete cycle, which like a musical overture repeats all the themes to be treated in the play-life, love, and death.

Meyerhold’s stage is not and has never been a mere striving towards theatricality tho his effects are so brilliant and unusual that you forget the reason for them and tend not to notice the new content uncovered or interpreted. His technical inventiveness derives from a desire to mirror and explore life more fully by means of the theatre. His form derives from his content.

The production of Don Juan in 1910 is the beginning of Meyerhold’s “new manner”. Here fer the first time he worked without the stage curtain. He brought back the us, of the forestage. He lighted the auditorium as well as the stage, made use of the stage servant, Japanese manner.

But this was no effort at historical reconstruction for its own sake. Meyerhold’s productions have never been “revivals”; they are creations. He saw Moliere as the first of the masters of the stage of the Roi-Soleil who aimed to bring the action out of the middle of the deep stage into the apron, the very edge. Moliere, according to Meyerhold, needed to come before the proscenium to bring out fully and freely the overbubbling hilarity, to give space “to the expanse of his large, truthfully sincere touches, in order that the wave of denunciatory monologues of the author might reach the audience, in order to bring out fully the free gesture of the Moliere actor, his gymnastic movements unimpeded by the colonnades of the wings.” The proscenium molds the acting. The forestage will not tolerate an actor with an inflated affectation, with insufficient elasticity of bodily movement. The dancing, movement, gestures, of the Moliere actor must aim not to make him the “unit of an illusion,” but to express fully all the designs of the playwright. In the old theatre the actor was the only one who could and had to convey the creative design of the playwright. Thus, having chosen the proscenium as the only traditional platform fit for a Moliere play, Meyerhold speaks consistently about the necessity of restoring the technique of the proscenium acting, of tricks natural to the old scenes, of the vivid lighting of the auditorium, and finally the analogue of the old Japanese Kurambo, the stage servant.

THE second problem in Don Juan was to create the environment. Meyerhold holds that the full grasp of some plays require the reproduction of an environment such as enveloped the audience for whom they were written. Apart from the epoch which created the genius of the author, this script might give the impression of a tedious tho charming play. In order that the modern audience might listen without getting bored by the long monologues and altogether foreign dialogue, Meyerhold held it necessary “to become intimately familiar with the most trivial traits of the epoch which created that work.” In recreating the perfumed, parasitic Versailles court against which Moliere’s comedy temperament struck out, Meyerhold supplied the second party to the conflict which is not contained in the script because originally it existed. in the audience: the Versailles stiffness, the dissonance between the king and the poet, the sharpness of the Moliere grotesque against the luxuriously decorated proscenium.

Since Don Juan there has been a steady and uninterrupted development of his art, a development that flowered under the Revolution, fostered and inspired by a new, sympathetic, audience. There is a widespread misconception of Meyerhold as a sort of will-o-the-wisp, changing his shape in each production, never continuing in any one direction, continually breaking with his past achievements, affirming his theoretic beliefs one moment only to throw them overboard the next. This impression is created by the unusual, spectacular and original nature of each of his performances, which so dazzles the observer that he sees no more than this, and those elements in his work which have steadily and continuously developed are lost to sight. The judgment is fostered by his own statement, made in 1913, that the director should never codify his theory, but should simply state to his co-workers the premises on which each production is to be based.

During the early period of the proletarian revolution the old academic theatres maintained, to justify their existence, that they were the guardians of the authentic traditions of the past, “the only basis on which the new proletarian art can be built.” In 1920 Meyerhold, the leader of the revolutionary front, wrote an article accusing the academic theatres of

“deliberately and systematically destroying the traditions of the great masters of the theatre, of diligently cultivating the theatrical rubbish of the second half of the XIXth century, the most poverty-stricken and hopeless of all the periods in the history of the Russian theatre. I accuse all those who hide behind the fetish of imaginary traditions of not knowing how to preserve the authentic traditions of Schtchepkin, Shumsky, Sadovsky, Lensky.” (Russian actors of the XIXth century.)

Coming especially at the time it did, this statement is of the utmost importance for the understanding of the work of Meyerhold. Since 1910, in his productions and in the work in his Studio he has tried to study the classic periods in order to discover those rules arising out of the very basis of theatrical material. But this work is not an absorption with purely technical problems. It aims to restore and continue the line of the “folk-theatre”, lost in the bourgeois epoch of our history.

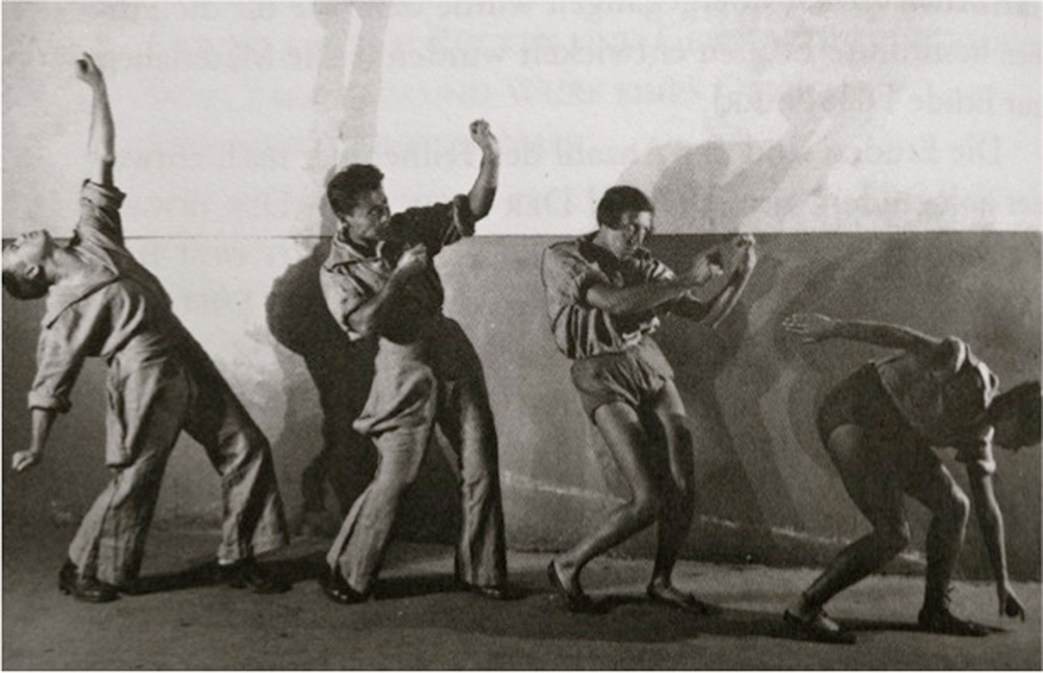

THIS folk theatre however, is not to be confused with the liberal idea of a people’s theatre or with the popular theatre which we know. Popular theatre is no more than the sunken theatre of the upper classes permeated to the masses in the period of its decay. Folk-Theatre is indigenous and class-conscious. It rises from the masses whose interests it represents, as against the theatre of the upper classes. In the various periods of its existence, whether in the theatre of the Greek mimes or the old Roman comedy of the masks, the medieval histrion-jongleurs or the old Russian zanies, the Italian Commedia del’Arte or the wandering actors of England and Spain, the creators of the profoundly national theatrical systems, as in the folk theatre of Japan or China- “everywhere we find such traits of resemblance that we are able to discern a single style of folk theatre common to all.” The distinguishing features of that theatre are: (1) Independence from literature and gravitation toward improvisation; (2) the prevalence of movement and gesture over the word; (3) the lack of psychologic motivation of acting; (4) a rich and trenchant comic quality; (5) easy transitions from the lofty-heroic to the base and the ugly-misshapen and comical; (6) the spontaneous combination of ardent rhetoric with exaggerated buffonade; (7) an effort at generalization, synthesizing of the characters by singling out sharply a given feature of the character, leading thus to the creation of conventional theatrical figures masks; (8) the lack of any differentiation of the functions of the actor: the coalescence of the actor with the acrobat, jongleur, clown, juggler, mountebank, songster, fool; (9) the universal technique of acting conditioned by this versatility, built upon the mastery of one’s own body, upon an innate rhymicality, upon an expeditious and economical use of one’s movements.

As Mokalsky writes in The Revolution of Tradition in the forthcoming Theatrical October:

“In their totality all these singularities form a pure theatre of actor’s craftmanship, independent of the other arts whose role in the theatre becomes merely auxiliary. The folk theatre is free from the esthetic pretensions of the aristocratic and bourgeois theatres; it does not endeavor to create an esthetically gorgeous and immobile show to feast the eye, and that is why it can do without the painter-designer. The decorations of the scenic platform and the actor are confined to the minimum necessary.”

If we examine Meyerhold’s work carefully we find that the continuation and development upon a higher level on the basis of a new content of this type of theatre is the key to all his work since 1910. The technical means which he has developed: the breaking up of a play into episodes, the musical principle, emphasizing the secondary characters and introducing new ones sometimes without any line, foreplay, transformation, the principle of grotesque, playing with objects, etc., etc., must be closely studied by all students of theatre to whom the problem of producing a play is a creative problem of interpretation and comment.

The New Theatre continued Workers Theatre. Workers Theatre began in New York City in 1931 as the publication of The Workers Laboratory Theatre collective, an agitprop group associated with Workers International Relief, becoming the League of Workers Theaters, section of the International Union of Revolutionary Theatre of the Comintern. The rough production values of the first years were replaced by a color magazine as it became primarily associated with the New Theatre. It contains a wealth of left cultural history and ideas. Published roughly monthly were Workers Theater from April 1931-July/Aug 1933, New Theatre from Sept/Oct 1933-November 1937, New Theater and Film from April and March of 1937, (only two issues).

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workers-theatre/v1n08-sep-1934-New-Theatre.pdf