Remarkable first-person accounts of the 1913-1914 Colorado Mine War in which the Ludlow Massacre was the turning point. Industrial Pioneer editor A.S. Embree interviews two veterans of the struggle a decade before. One, the mother of a mining family in the tent colony when the massacre occurred; the other an extensive interview with ‘X’, a miner and union leader from Aguilar who commanded a column of strikers during the War as he recalls the events leading to the conflagration, the battles of Cement Bridge and Deep Cut, the massacre at Ludlow, the miners’ retreat, the defeat of the state troopers, and the truce. A treasure.

‘Ludlow’ by A.S. Embree from the Industrial Pioneer. Vol. 4 No. 3. July, 1926.

ALTHOUGH I have read several stories of the Ludlow massacre and the events leading up to it, I have always been desirous of hearing the story at first hand from someone who had been in the struggle. So when I heard that X had taken an, active part in the strike and battles, indeed, that he had been in command of the strikers in the tent colony at Aguilar, I went after him and gave him no rest until he consented to tell me the story:

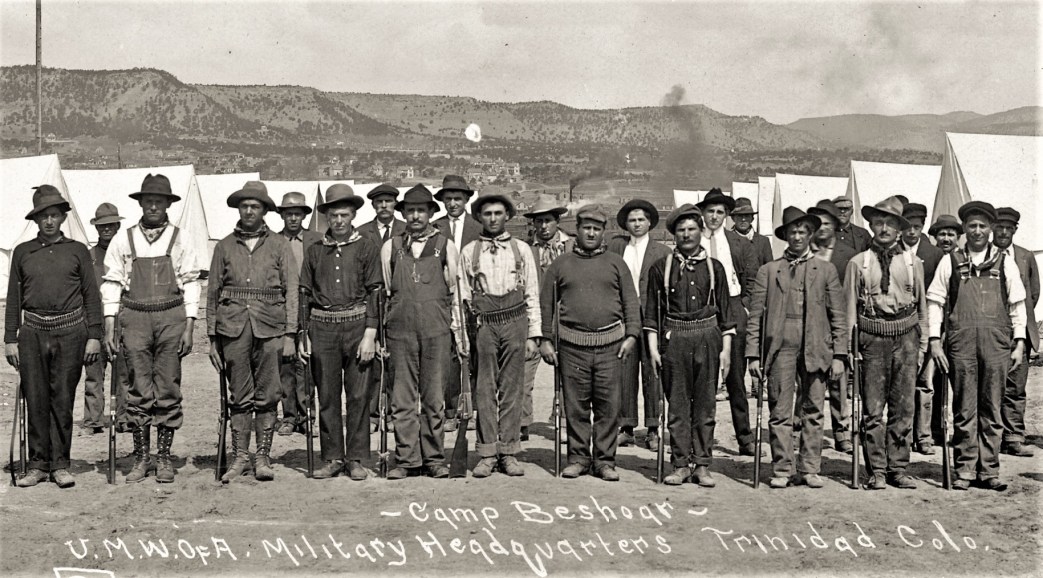

Soon after the strike started in 1913 I was put in charge of the strikers who were concentrated in our tent colony at Aguilar. Our colony was located on a flat which was then just outside the city limits of Aguilar.

The first incident I remember after we got located, was that the Empire Co. imported gunmen and they established themselves on a hill about 600 feet away and started shooting towards the town. The citizens objected to this shooting and the Marshall and about 50 of the citizens went up the hill and protested. They arrested one of the gunmen and brought him in and they reported that these gunmen were trying to start trouble.

Soon after that we had a payday — that is, money had been sent in from the international office for strikers’ relief and was being distributed.

Naturally, the strikers flocked into town to get their money. On the street I met a man who had come in from Black Diamond, about seven miles out, and I knew when I saw him that he was a gunman, I spoke to him and he asked me why there were so many people on the street. I told him he knew there was a strike on and added, “I know you are a gunman and if you want to avoid trouble you had better leave town,” He replied that he would leave town if he could get a horse and buggy. I walked toward the livery barn with him but on the way he stepped into the bank and asked to use the phone. Another striker and myself stepped behind the door where we could hear what he said. He called up the Empire Co. and said, “Tell the boys to come in and to bring Winchesters and six-shooters; I have plenty of ammunition but need a rifle.” When he finished phoning we grabbed him, took him to the livery barn, made him hire a horse and buggy and started him for Black Diamond.

Someone phoned to the Rugby tent colony about 4 miles north of Aguilar and told the strikers there he was coming. Before he got to Rugby he was beaten badly and died while being taken to Pueblo.

A week later a detachment of state troops came to our tent colony about 8:30 in the evening; Major Hamrock and Captain Garwood were in command. They came to[ the gate and demanded admission. The pickets reported that the major wanted to speak with me, so we admitted the officers only.

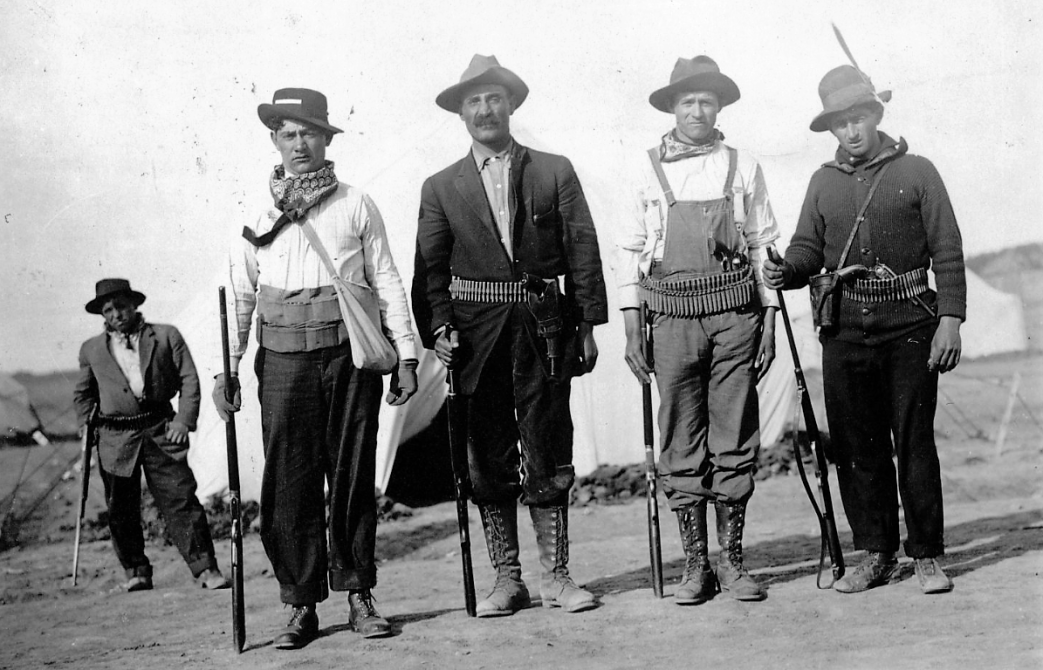

Major Hamrock told me the soldiers had disarmed all the gunmen along the line, and if there were any gunmen in or around Aguilar they would disarm them too. Then he said he would give us a square deal and asked that the strikers give up their arms. I told the Major we had only 14 guns for guard duty. The officers then withdrew and the troops were placed in permanent quarters.

Soldiers Make Trouble.

Everything went along quietly then for two weeks. The saloons were open and the first sign of disturbance came when the soldiers started drinking. Then the troops began to beat up citizens and strikers and the officers sent out details to arrest strikers. I was arrested and held in the guardhouse for two hours and released after an ordeal of questioning.

Then a company of cavalry was sent in. The mounted soldiers paraded the streets daily running citizens and strikers off the sidewalks. They also started drinking and there were wild orgies every night. They shot up the Princess Theatre — a man on the street was shot in the neck and badly injured. The soldiers went into the saloons demanding drink and if the bartender refused they shot up the place. In one saloon, four men were sitting at a table playing cards; one of them, Pete Garlevo, was shot through the arm by a soldier. Years later the state paid him $10,000 damages. When the soldiers got drinks they had the bartender charge it to the state. One saloonkeeper had $7,000 on his books which he was never able to collect.

Girl Kidnapped and Assaulted.

About a week after the cavalry company came in one of Aguilar’s best citizens was walking up the street about seven in the evening with his daughter who was about fifteen years of age. Two militiamen coming towards them separated to let this man and his daughter pass between them. As they passed one of the soldiers hit the father on the head with a gun stunning him. The girl was kidnapped and assaulted, but was returned to her parents about ten days later. She lived and gave birth to a child.

As an instance of what was happening at all hours of the day a striker named — and myself were passing the theatre on our way from a strikers’ meeting. We stopped to look at the bills advertising the show when two of the militia came up and prodded us with their bayonets, cursed us and ordered us to get back to the tent colony.

One afternoon Major Hamrock with a captain and a lieutenant came to the colony and asked us why we had pits dug all around the enclosure. We told him they were for refuse — empty cans, ashes, etc. He ordered us to fill them up. Three days after this three companies of infantry and one of cavalry searched our tents for arms but found none. Shortly after these troops left Aguilar and went to Ludlow and a week later Adjutant-General Chase came to Aguilar with troops and three pieces of artillery which he paraded through the streets and then left for Ludlow.

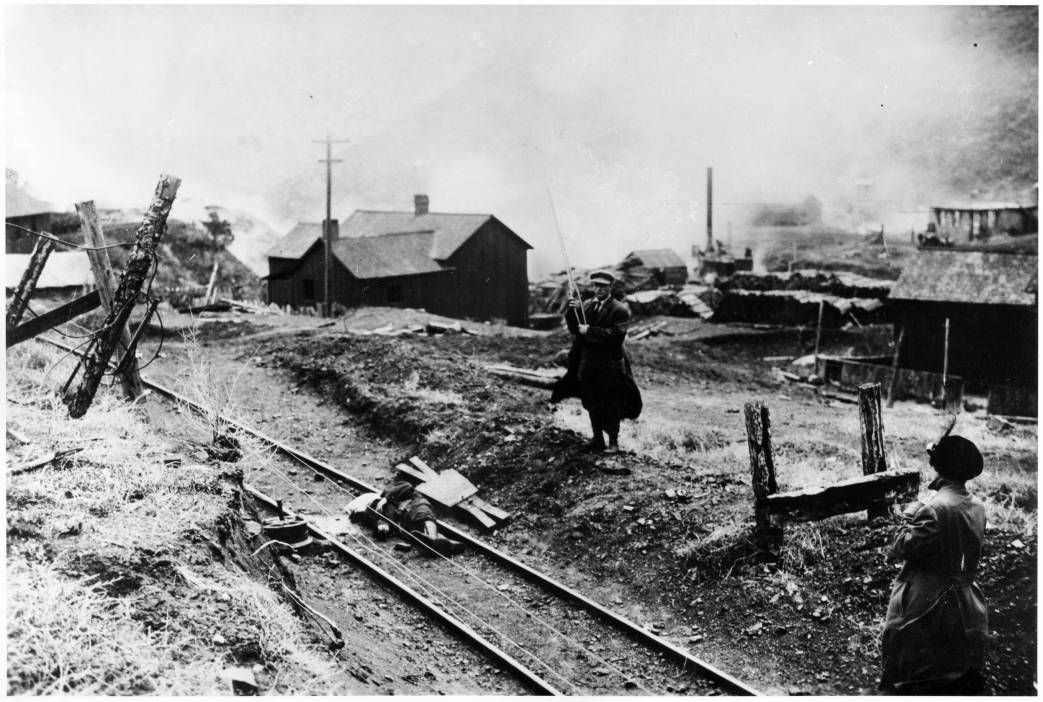

Cement Bridge Battle.

A few days later at 7:30 in the evening, I received a phone message from the Ludlow tent colony to get 60 men with full equipment and proceed at once to Ludlow. Some of our men were in the tents and some of them were around town. To gather them together I went to the fire station and rang the fire bell. A business man came along and protested telling me I could be fined for ringing the bell when there was no fire but I had no time to argue with him so simply pushed him out of the way.

We got our 60 men (could have had 500, but without equipment) and went to Ludlow and made camp. I reported to the officer in charge and asked for instruction and was told to have the men ready for action. All that night a huge searchlight stationed on the hill at the Hastings Co. mine played over the tent colony, and our outposts reported that about 250 men were advancing toward the colony. At daybreak these gunmen were reported to be close in but no attack was made. Noon came and still no attack. The Aguilar contingent was to eat first and while we were eating shooting started from the Cement Bridge and Water Tank Hill. Then I got orders for the Aguilar men to move from the tent colony across Green’s pasture making a flank movement toward the rear of the attacking body. The pasture was a mile wide and three-quarter mile long with pinion trees growing along one edge. A railroad track ran along the side of the pasture nearest the tent colony. I asked if they were sure that none of the gunmen were ambushed in the pinions and was told that the pinions were kept under observation and that they believed they were clear.

We advanced in skirmish formation and had almost succeeded in crossing the pasture, coming within, 400 feet of the pinions, when gunmen ambushed there opened fire on us. We were compelled to retreat and went back to the railroad track followed by the gunmen. At the track we made a stand behind the embankment, using the rail for gunrests, the men stationed 15 feet apart. One Italian boy persisted in sticking close by me. During this engagement a shot hit the rail between us — an explosive bullet, wounding the Italian boy seriously and myself slightly. The main body of the strikers drove back the attacking force at Cement Bridge and we compelled the gunmen facing us to retreat. Among the strikers there were five wounded while the gunmen lost seven killed and 20 wounded.

The next day we returned to Aguilar as we got a report that 50 mounted guards were advancing from the Lester mine to make an attack on the Aguilar colony. At six in the evening I got a phone message that these guards had passed Rugby on the way to Aguilar. This was early in the month of April and a snowstorm with wind amounting to a blizzard made it impossible for us to see clearly. We stationed our men in two groups of 50 each, east and west of the north road along which the guards were advancing, the groups being about 300 feet apart to avoid the danger of shooting one another. The group on the east side of the road allowed a team and wagon to pass, but confused by the blizzard, a few of the men started firing after it got past; so when the team and wagon came towards the group on the west side we also started shooting and killed both the horses. Soon after a car came along and stopped to pull the wagon to town; still confused we fired again breaking the windshield on the car and almost hitting a woman. Then we discovered our mistake, explained matters and made arrangements to take them to town and pay the damages.

In the meantime the guards had advanced to within a quarter of a mile of our position, heard the shooting and retreated.

Deep Cut Battle.

A few days later we were informed that the companies were recruiting an army of Baldwin Felts detectives, thugs and gunmen from other parts of Colorado and from Texas and Arizona, and a few deputies as well. This force was being gathered at Trinidad, and our men at that point kept us informed on what was going on. It was not long until we got word to prepare for an attack on the Ludlow tent colony.

This attacking party was furnished by the mining companies and the Colorado & Southern Railway with four steel gondolas to be used as armored cars, and a locomotive. Not one of the union engineers or firemen would consent to run the train. So an ex-engineer who had scabbed during the last railroad strike volunteered to pull the train and one of the Baldwin-Felts detectives served as fireman.

When we got word that this train had left Trinidad (the Aguilar contingent having again gone to Ludlow) a strong force of armed miners was sent to intercept the train. At a point about a quarter mile south of the tent colony where a steel bridge crosses an arroyo and a deep cut lies west of the bridge on a curve in the track, we placed our men on each side of the cut after blocking the track with old railway ties.

The engineer did not see the obstruction until he got well into the cut but as he was running slowly he brought the train to a standstill before hitting the ties. We could see straight down into the steel cars, and the attack began soon as the train stopped. The engineer was killed immediately; it was some time before the Baldwin Felts detective got the train started back and in the meantime the shooting was fast and furious and lasted until the train was out of range.

We had no casualties. Our friends in Trinidad sent us word that they had seen 35 bodies taken to the morgue and that as many more wounded were taken to the hospitals.

The Ball Game.

These events bring us up to the 18th day of April, 1914. It was Sunday afternoon and a ball game had been arranged between the miners and a team from the militia.

There was a big crowd of spectators, most of them strikers and their sympathizers. There was a great deal of rooting and cheering as the miners had the best of the game all the way through. When the game ended with a victory for the miners the crowd went wild and the cheering was tremendous.

Col. Linderfelt seemed peeved that the miners had won the game and resented the cheering of the crowd. He was heard to remark: “That’s all right; you people have your holler today but we’ll have the roast tomorrow.”

The following (Monday) morning the militia came to the tent colony with a large force and searched the tents for arms and ammunition. They tore up the floors and destroyed beds and other furniture.

In the afternoon two militiamen came up to our picket lines with a white flag. They reported that Col. Linderfelt and Capt. Hamrock wanted an interview with Jim Filer and Louis Tikas, who were then officers in charge at the tent colony. These two men went with the militiamen to Linderfelt’s headquarters.

The miners’ outposts could see all that occurred although they could not hear the conversation. They could see that there was a heated debate and accordingly they watched proceedings closely. When the debate lasted about fifteen minutes they saw Linderfelt suddenly seize a rifle and shoot Tikas down. After he fell Linderfelt struck him over the head with the rifle butt. Someone else, the outposts could not see who, shot Filer. Both men were killed while under the protection of the flag of truce. We knew then that there must be a battle.

No other events of importance occurred on Monday, but both sides prepared for a fight.

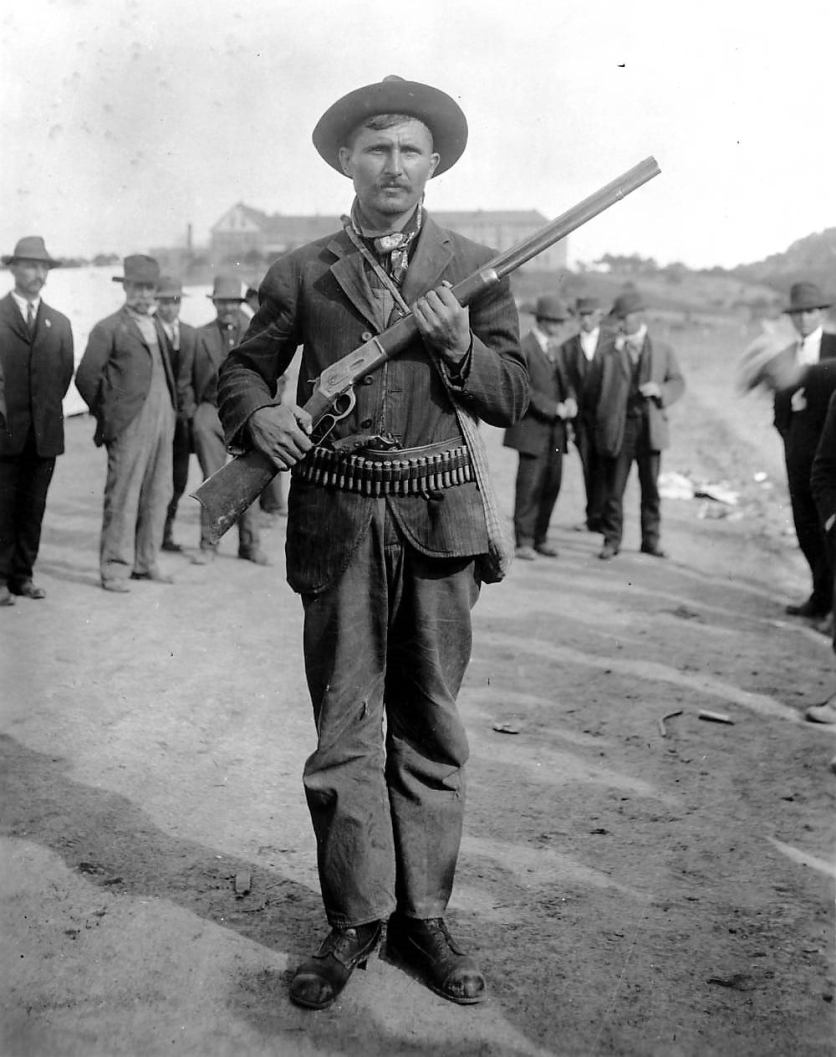

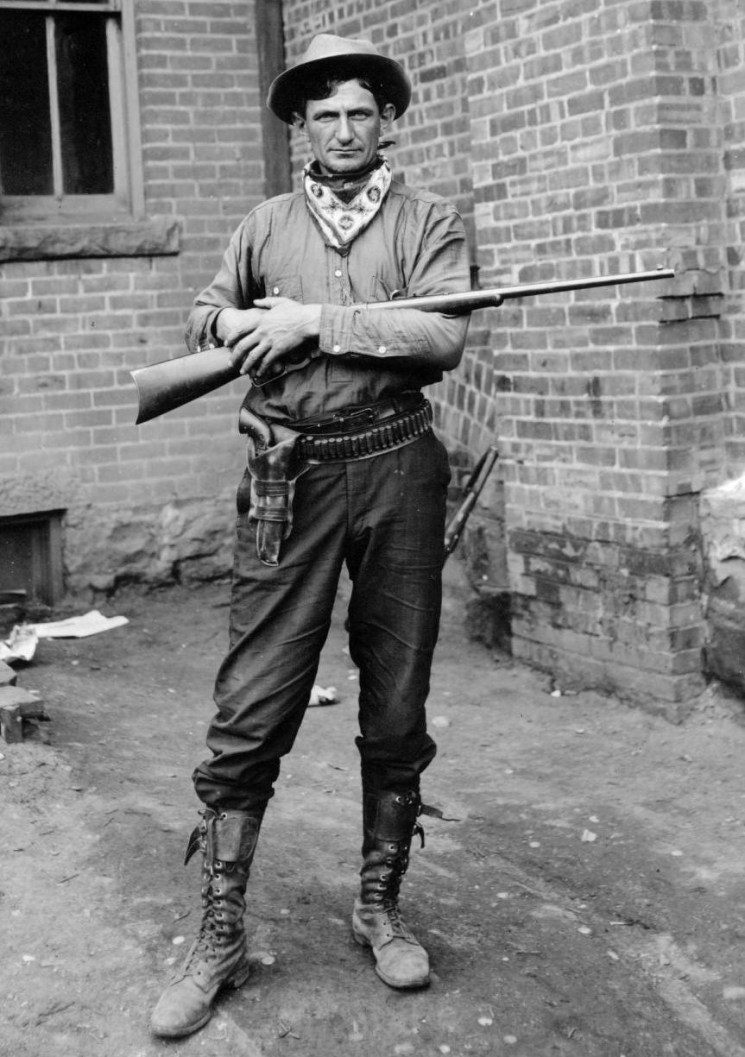

That day our contingent was in Aguilar and that night we received word of the killing of Tikas and Filer; also that a fight was inevitable. We had few guns and very little ammunition, but the miners insisted on going to Ludlow. Early Tuesday morning we started, 200 men with only 12 rifles and very little ammunition. Long before we reached Ludlow we heard the shooting. Our direct advance from the west was blocked by the militia; we were driven back but making a half circle we came into the tent colony from the east. When we arrived we found the attack was on in full force.

The Massacre.

That morning about seven o’clock the signal was given for the militia to attack. About 7 :30 they advanced on the tent colony in full force, 300 strong, well armed, with machine guns and three pieces of field artillery as well. They quickly drove in our outposts. There were 500 miners in the tent colony but after the seizure of arms the day before we had only 65 guns including the 12 in the Aguilar contingent, and a limited supply of ammunition. Yet with that small force we held the militia back all day covering the retreat of women, children and unarmed men to the Black Hills about three miles east of the tents. Some of the women and children would not leave their men who were fighting, others did not get started in time and these sought refuge in cellars under some of the tents; a number of them gathered in the basement under the floor of the mess tent. After we were finally driven back from the tents the soldiers rushed in and immediately began to saturate the tents with coal oil and set fire to them. Then as some of the women and children tried to run from the tents they were fired upon and struck down by the soldiers. One woman and her son of 14 leaped from a burning tent; soldiers standing near allowed the mother to come out but pushed the boy back into the tent were he was burned to death.

Charles Castro had been killed in the fight; his wife was cook at the mess tent; she and her three children would not leave without the father. With a number of others they went into the basement under the cook tent. When the big tent was fired by the soldiers they were all suffocated and burned to death in the Hell Hole.

The Retreat.

Those of us who were still fighting found that our ammunition was almost gone but we continued to cover the retreat of the unarmed until they reached the Black Hills. We were under fire from the four machine guns and the field guns, besides the rifle fire. But the retreat was made in good order.

On reaching the Black Hills we found that our water supply was half a mile out on the prairie. Whenever a man or a women went after water they were subjected to fire from the field guns. And then before dark we observed that we were almost surrounded by the militia.

We knew that our position was untenable and after a conference those in charge ordered camp fires to be made and kept burning and also that lights be kept burning in the tents to a late hour. Only one way was found to be open for retreat. Leaving the tents lighted and the campfires burning, we made our getaway successfully and reached Aguilar about daybreak.

In the morning the militia advanced in force on the Black Hills and captured the few vacant tents.

Soldiers Driven Out.

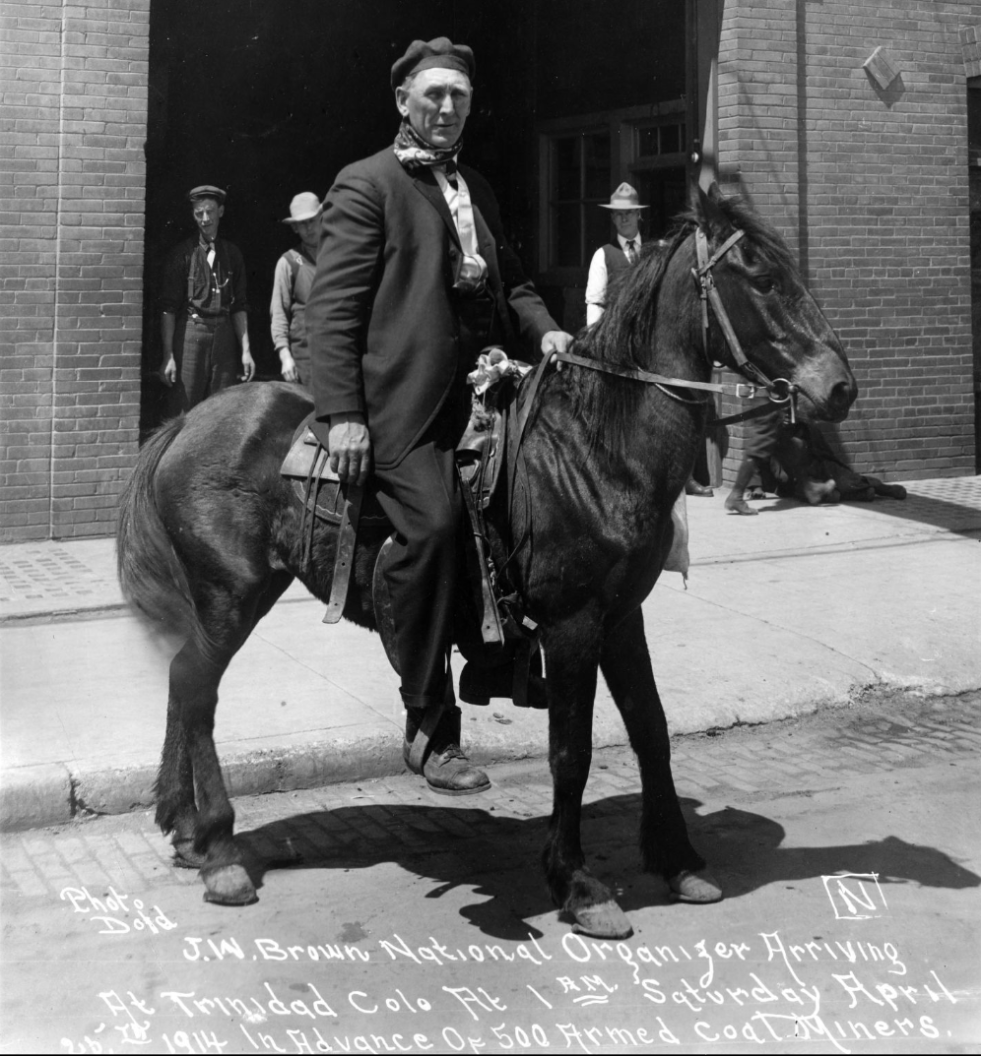

At Aguilar we commandeered schools and other public buildings to shelter the women and children. The story of the Ludlow massacre had reached the people of the entire country and aroused great indignation. Public opinion veered strongly to the side of the striking miners. Sympathizers by the hundreds volunteered their services and many companies of volunteers started on the march for Aguilar, quite a number of them from other states; 250 miners completely armed came in afoot from Fremont Co. The strikers obtained quantities of arms and ammunition. They made a general advance against the state troops and drove them out of Las Animas and Huerfano counties.

Gov. Ammons, seeing that his forces were beaten, asked for a three day truce. There was a considerable difference of opinion among the leaders of the strikers but the truce was finally agreed upon. Then the federal soldiers came in and that ended the war.

(That is the story. We continued to talk for an hour or two and he gave us many other items of events connected with the struggle. One or two of them may interest the reader.)

The mine owners at Hastings had succeeded in getting a few scabs. They had advertised in papers in the east promising they would give to each strikebreaker 160 acres of land adjacent to the mines, steady work and $5 a day. When they arrived they were taken under guard direct to the mines and lodged in shacks and herded by gunmen when not in the mine. If they refused to work they were driven to it by the gunmen. At night their shoes and clothing were taken away. But two of these men escaped. They came to Aguilar at ten o’clock one night clad only in their underwear and shirts. They made affidavits to the statement made above and also that four of the men who had refused to work had been killed by the gunmen and their bodies had been burned in the coke ovens.

At one time one of the Aguilar businessmen volunteered to drive his car to Pueblo and get a load of guns and ammunition. He had a Ford and had no trouble getting there. He made the purchase and started back. At that time the county road ran through Lester and one of the guards at the Lester mine stopped him at Bunker Hill. It was quite dark. The guard asked, “What have you got in the car?” Our friend replied, “Guns.” The guard stuck his head inside the car to have a look. The driver hit him over the head with a six-shooter knocking him cold, and drove through without any further trouble.

(In my excursions to the mining camps I have met many who have been through that terrible ordeal. A middle-aged woman, mother of a thirteen year-old girl told me the following:)

My husband and I were living in the Ludlow tent colony with our baby; she was four months old. About seven in the morning of April 20th we heard the first explosion (signal for attack by the militia.) Two other explosions followed, about five minutes apart. Then we could hear the machine guns and the bullets came whistling by our ears and through the tents. When some of these bullets struck anything — poof — they would explode and scatter pieces of lead all over. I went with my baby to a cellar under one of the tents and my man went to the railroad track to help fight the soldiers. They held the soldiers back all day and all the time I was in that cellar hearing the shooting and all the other noises of the battle. It was almost evening when my husband came back and we came out of the cellar and went to an arroyo on the other side of the Black Hills where we hid ourselves until morning.

While we were running away from the tents we looked back and could see the soldiers setting fire to the tents and could hear them shouting and shooting. They found one Italian woman afterwards in a cellar under one of the tents. She was going to have a baby and she suffered so much before she died that she had pulled all the hair out of her head.

When they drove us out of the company house we had taken all our belongings to the tent colony. We had no chance to take any of them with us and they were all burned by the soldiers. All we had then was the old clothes we were wearing.

My father had been living with us in the tent colony but we persuaded him to go to Trinidad early that morning before the attack began. When he heard of the fight and massacre he came to Ludlow the following day and searched the ruins of the tent colony trying to find out if we had been killed. The soldiers found him raking through the ashes and took him to the guard house where they kept him locked up for four days. His anxiety brought on a severe sickness so they brought him down to Trinidad. He was partially paralyzed. In the meantime we had managed to get to Trinidad and I was sick and dreadfully worried when I heard my father had gone to Ludlow looking for me.

He told us afterwards that the strikers who had been taken prisoners by the militia were compelled to work hard every day and if they refused to work they were whipped.

I have never been well since that day.

————–

These are the stories of only two of those who survived that historic struggle. There is wealth of material among the miners who have been through the 1913-14 strike and battles in Colorado for anyone who has the gift of putting it in writing.

And among these tried and true fighters for the cause of Labor there is again stirring the spirit and determination to organize and demand and obtain more of the good things of life for themselves and their families.

The Industrial Pioneer was published monthly by Industrial Workers of the World’s General Executive Board in Chicago from 1921 to 1926 taking over from One Big Union Monthly when its editor, John Sandgren, was replaced for his anti-Communism, alienating the non-Communist majority of IWW. The Industrial Pioneer declined after the 1924 split in the IWW, in part over centralization and adherence to the Red International of Labour Unions (RILU) and ceased in 1926.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/case_hd_8055_i4_r67_box_007/case_hd_8055_i4_r67_box_007.pdf