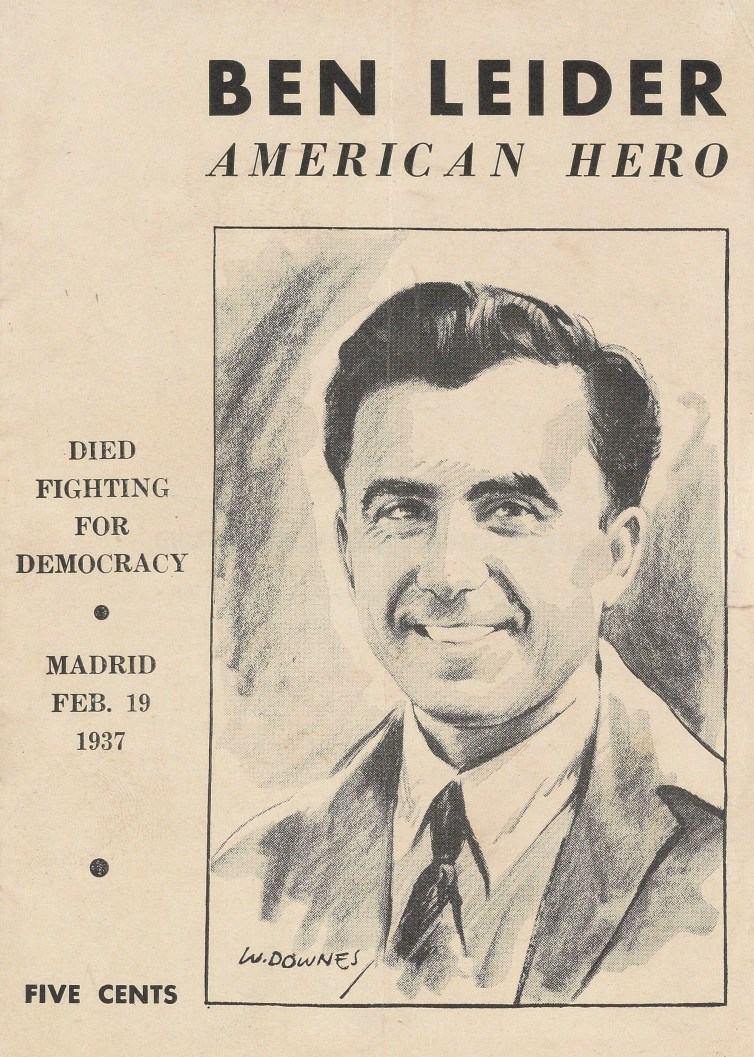

A friend and comrade remembers Ben Leider, the first American to die fighting in the Spanish Civil War. Benjamin Leider was born in Russia in 1901 and came to Brooklyn with his family as a child. There he attended City College for journalism and became politically active. Obsessed with flying, he became a pilot and flying reporter and aerial photographer. Active in his union, Ben was also a member of the Communist Party. He joined the Republican air force in September 1936 flying transport planes. He received training as a fighter pilot and was assigned to Alcala de Henares north of Madrid. Ben Leider was killed on February 19, 1937, shot down by fascists over the Jarama front.

‘In Memoriam, Ben Leider’ by Ruth McKenny from The New Masses. Vol. 22 No. 12. March 16, 1937.

The newspaperman-aviator who recently died in Spain left a heritage of which we can be proud.

BEN LEIDER, my friend, is dead. He was an American aviator, killed in action, fighting for the freedom of Spain and of the world.

I do not like people who parade their private sorrows before the world, asking strangers to mourn their dead. But Ben’s death is no private wound to lick in some dark corner. His death is your sorrow, as it is mine.

Ben died last month, shot down by some German or Italian plane. He must have died, as aviators do, in a blinding glare of fire, and with the whine of his falling plane and the sickening sound of the crash as his requiem. I hope that his death was sudden: only a sharp report, only a few minutes of the terrible fall through space, and then blackness. But even if he died in a single moment, there was still time for an agony of regret, a lifetime of fear.

I knew Ben Leider- and what pain to write of him now in the past tense-and I am absolutely certain that even in those last moments, even when the earth rushed up at him like a giant’s brutal hand, to crush and kill him, even when he knew that his life was all but over, that even then he had no fear and no regret. I know, as I can spell my name or tell you my address, that Ben was proud to die for the freedom of working people everywhere.

This Ben Leider who died last month in Spain- it should be easy for me to tell you about him. He was a very simple person, not pretentious, not sophisticated. It should be easy, but the pain and the loneliness left by his death keep getting in the way of the words.

Only two things in life mattered to Ben. The first was the Communist Party and the other was flying. He never separated the two. He was absolutely certain that one day he would use his aviator’s skill to fight for working people. Yet- and this will seem strange to those who know their newspapermen from the movies-Ben was a talented and capable New York reporter. But even among his own kind, the newspapermen, Ben was very quiet, shy, almost lonely. His face, dark and rather handsome, was customarily grave, his black eyes ordinarily bitter and stern.

But for those few who finally had the rare fortune to call this man a friend, the silence dissolved into eager talk, the grave eyes lighted with fire from the heart. We learned to know Ben through working with him in the Newspaper Guild. Although he wanted every spare moment to be at the airport with his little plane-the plane he bought from going without lunches, with painful savings from a reporter’s salary- he worked faithfully night after night for his union.

Once we walked through the quiet Greenwich Village streets together after one of the endless meetings. We were tired and at first we walked silently. Then suddenly he began to talk-in the beginning casually, and then bitterly and fiercely.

“Listen,” he muttered, “I’m not such a great talker as some of you guys, and I don’t say so much. But listen, I couldn’t sleep nights thinking about kids in this country not eating regular, thinking about what Hitler has done to the poor little guys in Germany, even if I weren’t a Communist.”

I said, “Yes,” looking at the pavement, feeling a little embarrassed. Now Ben stopped still, and you could see his fists clenched in his pockets.

“My mother damned near killed herself working so her kids could have schoolbooks and get an education,” Ben said, and his voice was almost a growl it was so bitter; “and I’m not one of those guys who forget where they came from when they get some middle-class job and start eating regular.” He scowled. “Listen, I know about poor people; Jesus, how I know. And how it burns me up, what the big guys do to them.”

We stood still there in the quiet street. A cab went by, going fast, and you could hear its radio blaring some cheap, sad tune as it went down Seventh Avenue.

Finally Ben spoke again, his voice rasping with the difficulty of saying the words. “Look, I ain’t hot on dying; I got too many things to do. I got a way of taking pictures from the air worked out that I figure will help the boys over in the Soviet Union, and a lot of other things. But I ain’t kidding myself. You take your chances even flying the mail, and dodging machine-gun bullets in an airplane is no way to live to a ripe old age.”

“Ben, Ben,” I said looking away in a sudden feeling of sorrow.

“I want to do it,” he answered fiercely. He paused, and his voice turned tender and sweet. “Jesus, I never cover a story in Williamsburg or walk down Catherine Street, without watching the dirty, hungry little kids. I look at ’em and I think, ‘never mind, you kids, never mind, we’ll fix it up for you.’ And we will, too, by God!” He turned and looked directly at me. “You think it isn’t worth dying for?” he asked.

So Ben is dead now, before he told the boys in the Soviet Union about the way he had of taking pictures from the air. He is dead, and he was only thirty-six years old. He was a young man, and his life had been difficult and hard. He is dead, and my little brother Jack who is just fourteen, cried last night, when I told him that his friend, Ben Leider, had been killed in Spain.

I never knew a man who was so tender and gay with children as Ben. I took Jack out to Roosevelt Field one day last summer for his first airplane ride. Jack was so excited, when the great moment came, that he had to screw up his freckled snub nose to keep the nervous tears from his shining blue eyes. Jack wants to be an aviator, you see, and all his life he had been waiting to really meet one. Ben took one look at my shy, nervous little brother, and then his own dark, grave face was lighted by a smile from the heart.

“Hi, Jack,” he said, very casually, as one aviator hails another, “give me a hand with checking the old crate over, will you?”

“Gee,” my brother said, and Ben smiled and put his arm around the boy’s shoulder. So Ben is dead now, before he had a son, and he loved children. He is dead, and his thin face, that I remember best lighted by a sudden brief smile, is destroyed. His death makes his friends who truly loved this silent, quiet man, full of loneliness.

Ben hated fascism, hated it darkly and fiercely. So of course Ben went to Spain. Naturally.

Ben would have hated the tears we cannot help but shed for him. The only epitaph he wanted was someone to take his place. He believed, as I believe, that the Spanish struggle for freedom is a life and death fight for world democracy. He died for it. Now what will you do for Spain? What will you, who still live, while Ben lies dead, what will you do to make sure that fascism does not pass?

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s to early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway, Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and more journalistic in its tone.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1937/v22n12-mar-16-1937-NM.pdf