Centered on the strike in Gastonia, the late 1920s saw a surge of militant action among Southern textile mill workers that presaged the C.I.O. of the following decade. Here William Z. Foster reports on the Southern District conference of the T.U.U.L. and its affiliate, the National Textile Workers Union.

‘The Historic Southern Conferences’ by William Z. Foster from Labor Defender. Vol. 4 No. 11. November, 1929.

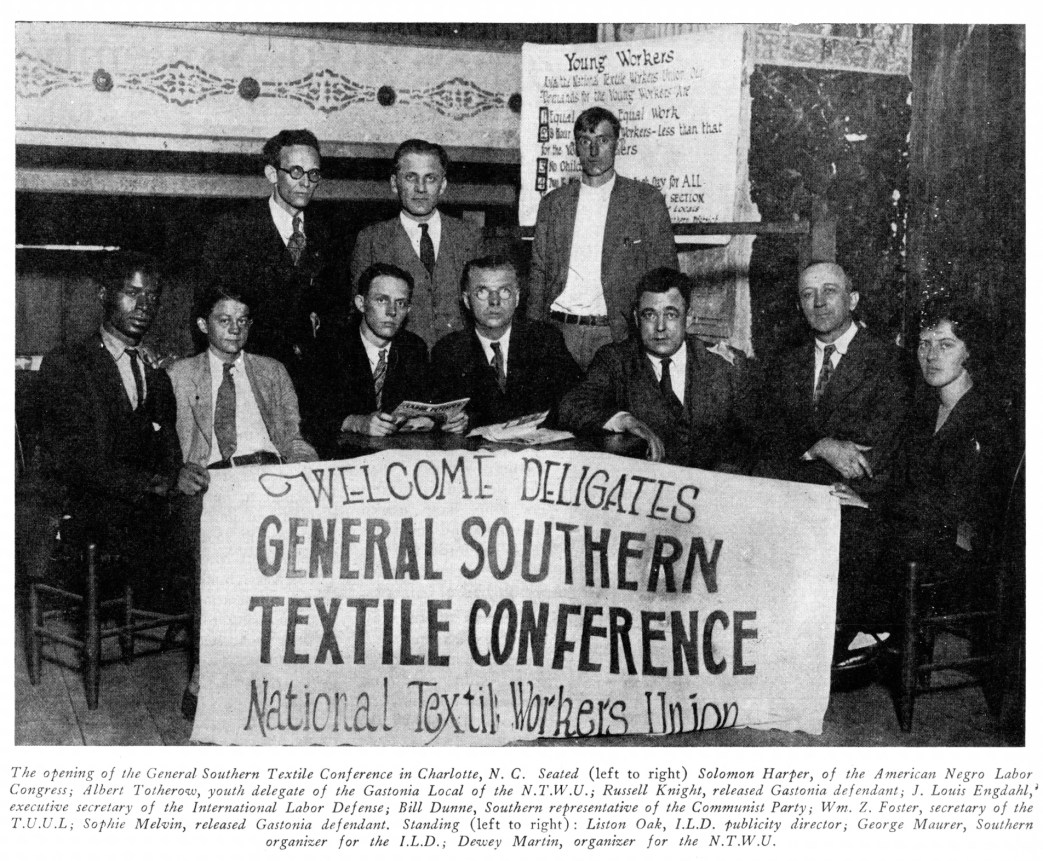

A STIRRING chapter was written in the history of the militant working class movement at Charlotte, N.C., October 12-13, at the conferences of the National Textile Workers’ Union and of the Southern district of the Trade Union Unity League.

In an atmosphere of terrorism, when it was uncertain if the bosses’ Black Hundred would go night-riding again, 287 delegates from 75 mills and 35 cities and 5 states, representing about 60,000 workers, attended the textile conference.

The T.U.U.L. general southern conference was made up of 40 delegates (exclusive of the textile delegates) coming from 17 cities and 8 states and included Marion workers, miners, building tradesmen, lumber workers, railroads, wood workers.

Had it not been for the atmosphere of terrorism and serious financial difficulties both conferences would have been two or three times as large.

A fighting spirit-which boded ill for wage-cut, speed-up, unemployment, poverty and pellagra-prevailed among the workers. They painted devastating pictures of rationalization in present day United States. One worker’s wages had been cut from $25 to $11 in the past two years while his work had been increased 200 percent. Wages in Georgia were reported to be from $6 to $19 for a week of 60 to 80 hours.

Stories of incredible brutality in the mills were on the lips of all the delegates. Old workers fired ruthlessly to make room for younger ones. The youth driven on the job at a wild pace for half what men get.

The women, especially, suffer amazing conditions. Delegates reported that when women stay more than two or three minutes in toilets they are unceremoniously routed out by the slave-driving “overseers.”

Against these hard conditions the delegates were in open revolt. They displayed intense faith in the National Textile Workers’ Union to lead them in their struggles. There was the utmost bitterness against the United Textile Workers’ Union, which betrayed them flagrantly in the strike in 1921. And they have not forgotten it.

American, to the last individual, they were not shocked by the revolutionary program of the T.U.U.L. nor by the violent newspaper campaign against the conference as Communist and Bolshevik. Their discontent blazed forth. Of tremendous importance was the unheard of role played by the Negroes at the conference. The sacred Jim Crow regulations were broken when Alexander and Harper, of the Labor Jury at the trial of the Gastonia strikers, and half a dozen more Negroes sat among the delegates.

And right here, in the heart of the brutally chauvinistic South, these Negroes dared take the platform and advocate racial equality and international co-operation. The white Southern workers reacted to this unparalleled situation in a greatly enlightening manner.

They appeared not to be a bit shocked, gates. although all their lives they have had race prejudices formed into them as a major principle of the ruling class. They vigorously applauded effective points made by the Negro speakers.

The textile conference adopted a manifesto with the following demands; abolition of the stretchout system, abolition of the 10 to 12-hour day; establishment of 8-hour day for adult and 6-hour day for young workers; abolition of night work and child labor; equal pay for equal work for men, women, Negro workers and youth; $20 minimum wages and recognition of the National Textile Workers’ Union.

It was well realized by the workers that since the T.U.U.L. and the N.T.W.U. had successfully resisted the attacks of the police and fascist gangs, that the A. F. of L. was to enter the field as a special reserve force of strike-breakers.

From every point of view the Charlotte Conferences were a success. They indicated anew the radicalization of the workers in the South, not only in textile but in other industries. They mapped out practical, concrete programs. It now remains for the T.U.U.L. to mobilize all its forces. The South is on the eve of great movements of the workers. The T.U.U.L. must head these mass struggles.

Labor Defender was published monthly from 1926 until 1937 by the International Labor Defense (ILD), a Workers Party of America, and later Communist Party-led, non-partisan defense organization founded by James Cannon and William Haywood while in Moscow, 1925 to support prisoners of the class war, victims of racism and imperialism, and the struggle against fascism. It included, poetry, letters from prisoners, and was heavily illustrated with photos, images, and cartoons. Labor Defender was the central organ of the Scottsboro and Sacco and Vanzetti defense campaigns. Editors included T. J. O’ Flaherty, Max Shactman, Karl Reeve, J. Louis Engdahl, William L. Patterson, Sasha Small, and Sender Garlin.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/labordefender/1929/v04n11-nov-1929-LD.pdf