Radical social psychologist Dr. Solomon Diamond investigates the psychology behind the wave of sit-downs and refutes mainstream and academic notions of the life-changing actions of the strikers.

‘The Psychology of the Sit-Down’ by Solomon Diamond from the New Masses. Vol. 24 No. 6. May 7, 1937.

IT was recently reported in the press that the head of the psychology department at one of or universities–famous above all for the height of its skyscraper structure- had decided that the sit-down strikes were a “mental epidemic,” in which many of “the sitters have not the slightest idea of why they are sitting.” He added that the method would soon become laughable, and “once laughable, sit-downs will become useless” -a prediction which may bring some comfort to Andrew Mellon, who is sometimes said to own both the city of Pittsburgh and its university.

This is a fair expression of an attitude which has been quite general among psychologists, who have followed the individualistic bias of our social order by considering that “crowd behavior” is something inferior to individual behavior, and that in it the actions of people are determined less by their intelligence than by their emotions. It is a theory that fits in admirably with Henry Ford’s, that every worker should shun unions as the plague. It has never been based upon a serious study of crowd phenomena or any other kind of cooperative activity. The sit-down strikes provide a good opportunity to test it. However, before turning to them, it is worth while to consider what the origins of this theory were.

The doctrine that people are necessarily more stupid and less civilized when they act together than when they act in isolation was first advanced in extended form 1by the Italian criminologist Sighele, in his book The Criminal Crowd, in 1892. Sighele himself drew attention to the fact that it was timely because of the widespread social unrest at the time. He drew his examples from the violence of peasants against tax collectors, from demonstrations of the unemployed in Rome, from the hunger riots which had taken place in Sicily five years before. He does not mention, but we may recall, that 1890 was the date of the first International May Day. It was a period of widespread militant activity by the working class, in Europe and America.

Sighele departed from the viewpoint of the Italian school of criminologists, who held that criminality was a recessive, hereditary trait, a form of atavism. He declared that crowds also were atavistic, swayed by primordial instincts rather than by intellectual considerations and the moralities of, civilized life. Twenty years later, Sighele presided at the first congress of the Italian Nationalists, forerunners of fascism. He added a note of “science” to their arguments against parliamentary government, and joined in their glorification of war. If he had lived a few years longer, he would undoubtedly have welcomed fascism.

Sighele’s theory was taken up and generalized further by the Frenchman LeBon, whose book is much better known. It is still one of the most widely read books in our public libraries, but those who read it are seldom aware of the background out of which it rises. LeBon has written many vicious attacks against socialism and trade-union activity generally, and his psychological theory of “the crowd” is designed to provide some semblance of scientific basis for these attacks. He explains the urgency of his book by writing:

“The masses are founding syndicates before which the authorities capitulate one after the other; they are also founding labor unions, which in spite of all economic laws tend to regulate the conditions of labor and wages. They return to the assemblies in which the government is vested, representatives utterly lacking initiative and independence, and reduced most often to nothing else than spokesmen of the committee that chose them.”

His theory of the crowd is generalized to include all forms of economic and political cooperative activity on the part of the masses. Like Sighele, he too is an anti-parliamentarian. If LeBon had not ended a long life of antidemocratic ranting several years ago, he would undoubtedly be providing us now with some very entertaining observations on the people’s front as well as the sit-down strikes, to which the French workers gave that envied Parisian touch.

Those who, at the present time, readily stigmatize such phenomena as sit-down strikes, or other working-class actions, as “crowd behavior,” or “mental epidemics,” are, I fear, actually responding to motivation very much like that of Sighele and LeBon. A serious scientific approach to these problems requires a real investigation of them, which involves a careful study of the individuals involved in the action, and not just a remote perspective of the “mass.”

WHEN ONE investigates the history of particular sit-down strikes, one finds that the first question to answer is not “Why did they sit down?” but “Why didn’t they strike before?” Despite low wages and bad conditions, workers have often hesitated to strike because they have been afraid. Above all, there is the perfectly rational fear of losing their jobs. This fear is allayed considerably by the sit-down technique. The worker who sits right on his job is not tormented by the hourly fear of losing it. In many of the sit-down strikes that have taken place, the workers have voted to strike on condition that the method used should be the sit-down, because they felt that, once out on the street, their chances of being fired were greatly increased. And the results of sit-down strikes have shown that this confidence in the method has been justified. I doubt that the worker’s “love for his machine” enters very much into his preference at being inside rather than outside. A job is above all else a job, and that is what they are holding on to.

But, besides this, workers are held back from striking by many irrational fears of social criticism. For example, they do not want to be seen in an inferior position, or they do not want to be associated with a movement that has a bad reputation, etc. These fears, also are met by the sit-down technique. The worker who sits down inside his shop does not feel that he has lost any social prestige.

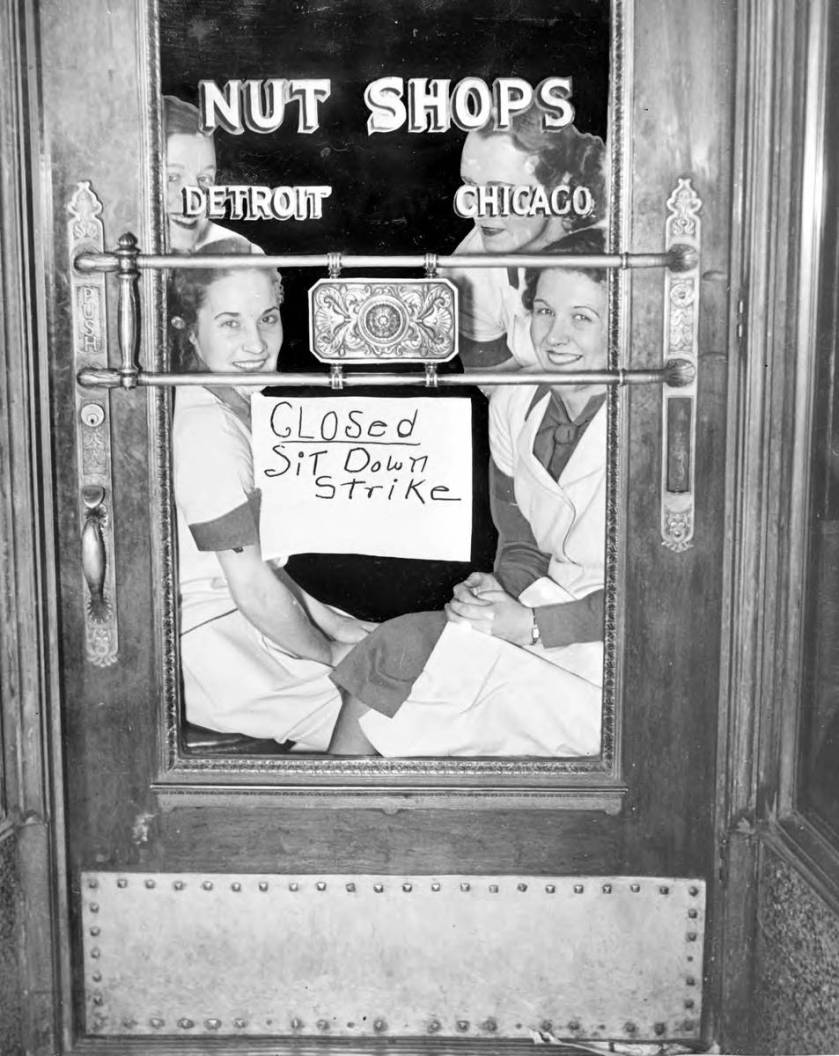

One of the most remarkable aspects of the sit-down strike, from the psychological viewpoint, is the paradox that this seemingly more radical technique, which has been denounced as an invasion of property rights and a “revolutionary exercise,” drew into strike actions, for the very first time sections of the working class that had hitherto been regarded as “unorganizable.” It was so in France, where the sales forces in the department stores and clerical workers in offices engaged in some of the most long-drawn-out struggles, and the union membership in these categories was literally multiplied tenfold in a very short period. It has been so in America, where the strikes of the Woolworth and Grand girls gave a stunning surprise both to their employers and to the working-class movement. These new recruits to militant unionism were not the victims of a “mental epidemic.” Rather, they were released from something which previously restrained them. And, all legalism to the contrary notwithstanding, it seems much more genteel to sit down and fold your arms than to march up and down with a picket sign.

Interviews I have had with sit-down strikers have convinced me that irrational emotional factors, of the sort that are supposed to be responsible for “mental epidemics,” play a much larger part in keeping workers back from striking than in leading them to strike. I came to a similar conclusion when, about a year ago, I made a study of personality factors in connection with political radicalism. The entry of the individual into such activity is likely to be the result of a struggle between intellectual conviction that favors participation and emotional inhibitions that restrain him from this unconventional step. That is one reason why Mr. Mellon should not take too much comfort from the thought that sit-downs may become less effective when they become “laughable.” The good humor which has accompanied sit-down strikes is one of the factors that has made it easier for many hitherto unorganized workers to overcome these emotional inhibitions.

The experience of participation in any strike for the first time always profoundly affects the personality of the striker. The conditions of the sit-down strike are such that this effect is especially intense, because for some days or weeks the ordinary family routine is interrupted, and the individual lives among new companions, in an atmosphere of cooperativeness which is rare in contemporary society. As a result, a new orientation in thought is taken. “We” replaces “I,” at first in thinking about the strike and its problems, but thereafter more generally. The new habit of thought invades, to lesser or greater degree, every segment of the individual’s behavior, bringing everywhere a healthier, freer, less introvert orientation. This process too must be regarded primarily as a breaking-down of irrational individualistic inhibitions which had formerly impeded the proper objective approach to both personal and political social situations.

THE HESITATION of an unorganized worker to enter into public cooperation with his fellow workers is only one expression of the introversion which, in greater or lesser degree, hampers most of us in our social activities. He does not judge this action merely in the light of the reasonable considerations, the common interest of those participating, the material benefits to be gained, the improved conditions sought, but also with regard to the way in which it exposes him, as an individual, to criticism. We have already mentioned the fact that the sit-down technique helps to overcome this inhibition. What I want to point out now is that the experience of participation in the strike generalizes this effect. The result, in the most striking cases, is a veritable revolution of the personality. These cases are referred to, usually, as persons in whom “latent abilities” have been revealed by the urgency of the strike situation. They are, in fact, persons whose abilities had hitherto been cramped and warped and are now suddenly released for free development.

I should like to add a few words about May Day. I think there are a great many people who can test the validity of my argument either out of their past experience or their present hesitations about marching in the May Day demonstration. How many of us feel the tug between intellectual convictions that we ought to march, to join with hundreds of thousands of others in demonstration of common purpose, and silly emotional inhibitions that try to hold us on the sidelines, just looking on! Are you afraid to submit to the infection of a “mental epidemic”? If you are nursing a protective capsule that insulates you from society, you owe it to yourself to step in line, and crack it!

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1937/v23n06-%5b07%5d-may-04-1937-NM.pdf