Grace Burnham, director of the Workers Health Bureau and writer for the Labor Research Association on the illness-inducing, life-threatening conditions faced by textile workers in Passaic, New Jersey.

‘What the Mills Do: Textile Disease in Passaic’ by Grace M. Burnham from Labor Age. Vol. 16 No. 6. June, 1927.

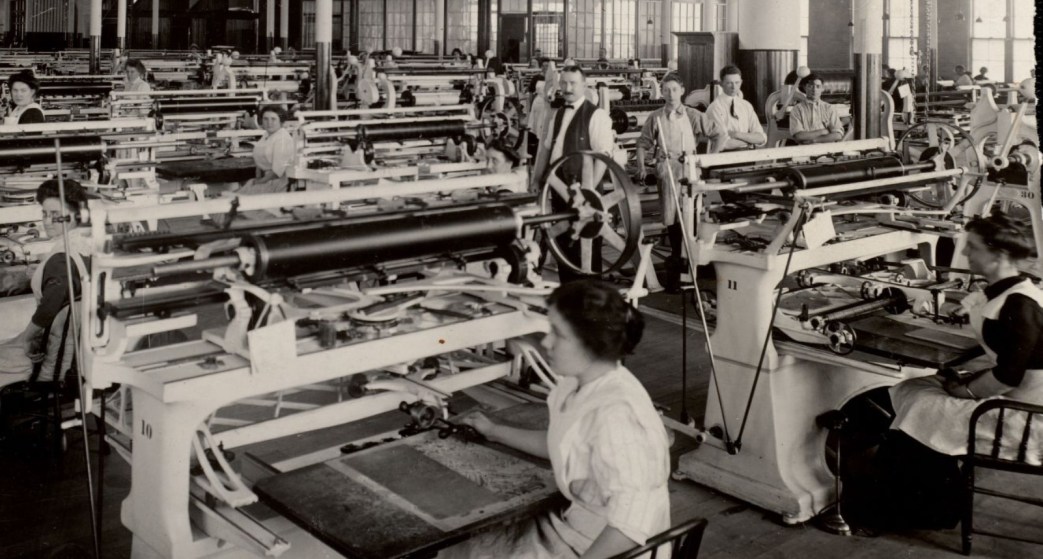

EXPOSURE to poisons, heat, steam, denial of the K most elemental sanitary provisions…hours averaging 59 a week…low wages…such are the degrading conditions of work which produce on the one hand the brilliant display of colored silks, velvets and other attractive fabrics in our shop windows…and on the other hand break down the bodies of the men, women and children employed in the dyeing and finishing of textiles. These inescapable facts are brought out in a report on “Health Hazards in the Dyeing and Finishing. of Textiles”, just issued by the Workers’ Health Bureau, as part of its study of 404 textile workers of Passaic, New Jersey and vicinity.

The dyeing and finishing of fabrics is becoming an increasingly important part of the textile industry. The strike committee of the Textile Strikers estimates the number of workers engaged in this branch of textiles in New Jersey in 1926 at no less than 11,000. Dyers make use of a great variety of poisonous substances such as coloring materials and bleaches. The workroom is often intensely hot and filled with steam. In addition to breathing the hot vapors and fumes, skin irritations are common and the scalding dyestuffs may spatter into the face, burn the skin and injure the eyes.

These conditions need not exist. Poisonous fumes can be controlled so that they are discharged into the open air, instead of into the workroom. Steam can be carried away by means of mechanical systems of ventilation. Hours of work in unavoidably hot processes can be reduced and other provisions made for the health of workers.

The 77 dye workers given medical examination by the Workers’ Health Bureau reported working conditions which disclose a flagrant disregard on the part of many of the employers of these essential protective measures, and an utter contempt for even such minimum standards as have already been written into the New Jersey Law. Reported hours of work are far in excess of union standards, running as high as 72 in one week. In many instances workers are deprived of their lunch hour. They complain bitterly of the heat, steam and fumes, and of the fact that there is no place to hang street clothes and ‘no possibility of changing from their soaking wet garments to dry ones before going home. Unspeakable sanitary conditions exist—relics of the early days of factory production. The results of the medical examinations give ample proof that human beings cannot withstand such exploitation.

Heart Disease…High Blood Pressure…Tuberculosis

Not one of the 77 dye workers given medical examinations by the Workers’ Health Bureau was free from physical defects. One third were found with heart disease, high blood pressure or both. These workers are the fathers of families who are dependent on their wages for support. Over exertion may mean invalidism for life. Yet these very men are doing the most exhausting work, exposed to poisons, heat and steam from 50 to 72 hours a week.

Three dye workers were found to have active tuberculosis and arrangements had to be made for immediate sanitorium care. Seven more have serious respiratory disturbances, which on further examination may prove to be tuberculosis. Ten or twelve hours of labor a day or night in soaking wet clothes, breathing the irritating fumes of acids and bleaches, can only mean inevitable breakdown to lungs already injured.

Eight out of every yen of the workers examined complain of severe irritations of the eyes, nose or throat…over one third were no longer able to digest their food, complaining of belching, cramps, nausea and frequent vomiting…over one third had constant headaches and almost as many more were suffering from rheumatism or muscular pains.

Twenty three dye workers reported that they had been the victims of industrial accidents. The injuries were caused by burns from caustic soda, acids and steam, falls, sprains, strains, falling of heavy weights, and the ripping of arms and hands by machinery. Some of these accidents resulted in permanent injury and disfigurement, and in one case, that of a boy 18 years old, a wrist broken by the frame machine, was so severely injured that this child is not only permanently disfigured but has lost the use of his hand for life.

Dye workers have a higher percentage of high blood pressure than painters who are exposed to all kinds of poisonous materials, a higher percentage of heart disease than painters, furriers or bakers, a higher percentage of tuberculosis and other respiratory diseases than printers, painters, food handlers or furriers. Compared with a representative group of general workers not exposed to general hazards such as Life Insurance Company Policyholders, dyers show 20 times the percentage of active and suspected tuberculosis…3 times the percentage for high blood pressure…and 14 times for heart disease.

Typical Cases of Exploitation

The histories of two workers examined tell a story of suffering, want and physical collapse for much of which the industry is directly responsible. The first, age 48, worked for 4 years in the boil off room. He starts work at 5 o’clock in the afternoon and quits at 20 minutes to 7 in the morning. During the night he gets 20 minutes for lunch. In the busy season he averages 70. hours a week. He complains of the heat, steam and fumes. His clothes are always dripping wet and there is no place to change before going home. Year before last he had the “flu”, and last year his thumb was caught in the machine and he was out of work for 4 months without a cent of compensation for the accident. He told the doctor he had headaches, pains in the legs and his ears bothered him. He didn’t think there was anything special the matter with him. He was found to have TUBERCULOSIS, PLEURISY, bronchitis, diabetes, anemia and hardening of the arteries.

The second worker earns from $15 to $20 a week for 65 hours labor. He has a wife and two children dependent on him. He had worked in the washing and drying department for two and a half years. Sixty-five hours work a week…so that “people sleep on the wet floor” from exhaustion. The toilets are described as a “trench in the ground, out of doors”, and “you go out in your wet clothes.” Wooden shoes are worn because the water and the steam “gives you rheumatism”. Other complaints were headaches and stomach trouble. The doctor found this worker 12 pounds underweight, anemic, with an enlarged thyroid, probably diabetes and a blood pressure far above the normal for his age. He is now 47 years old.

Stories of Mill Conditions

Descriptions of mill conditions given by the workers seem unbelievable, yet many similar to them were reported by the Consumers’ League of New Jersey in a Survey of Textile Mills in 1918.

The dye houses work day and night. The heat in some of the processes such as dyeing and drying is that of the tropics. The steam is so thick you cannot see the worker opposite you. Dangerous machines stand in this fog, and workers constantly run the risk of serious accidents from walking into them. The atmosphere is unbearable, filled as it is with the fumes from bleaches, acids and other chemicals. Floors are running with water, so that workers must wear rubber boots or wooden shoes for protection. Clothes are dripping with steam and perspiration. Yet workers are forced to work, ten, twelve, even fourteen hours a day or night during the rush season, and are left totally unprovided for in slack season when the market is glutted and mill owners hold their stocks of materials for better prices.

Twenty one workers reported that they were given no time for lunch but had to gulp down what they could as work goes on at the same time. Imagine eating lunch, day after day in a steaming hot room filled with the fumes of choking acids. No wonder that one third of the workers were found to have digestive disorders.

Rest rooms, wash rooms, places to keep street clothes and to change into dry garments before going home are in most instances unheard of. Mrs. Kelly in her report for the Consumers’ League in 1918 says: “Many workers were dressing before their machines at closing time. One of the women said: ‘You have to walk through the room with your eyes shut!’…She also reported “that women were trying to steal a few minutes rest by sitting in the primitive toilets, which were narrow boards, in which holes were set over a common trough, flushed automatically at intervals.” Fifteen workers stated that they were forced to use such troughs in 1926…thirty workers stated that toilets were foul or filthy.

With even these common decencies denied it is not surprising to find-the basic hazards of the industry— heat, steam and poisonous fumes—still largely uncontrolled.

These Occupational Diseases Preventable

Dr. Alice Hamilton, acknowledged authority on industrial poisons in the United States, and author of a standard text book on the subject, referring to the Workers’ Health Bureau report says: “The unhealthful conditions described as existing in these New Jersey dye works are almost entirely preventable…the atmosphere in these plants resembles that of the tropics, and yet men are expected to work at full speed ten, eleven and even twelve hours a day. “The high rate of tuberculosis, heart disease and other serious defects found is probably traceable to the working conditions in the industry.”

Tuberculosis in dye works…the result of long hours of needless exposure to fumes, sudden changes in temperature, heat, steam, and the denial of provisions for bodily comfort and hygiene is PREVENTABLE. Heart Disease and High Blood Pressure…from poisons, over-exertion, rheumatism are PREVENTABLE. NOT ONE of the 77 dye workers examined is free from physical defect.

No wonder these workers rose in mass protest, determined to win for themselves a union which will wrest from the employers decent standards of hours, wages and working conditions.

In contrast to the 60-70 hour week of the dye workers, a Survey of Organized Trades in 1925 showed an average working week of 4514 hours. Organized painters and furriers have established the 40 hour week. The garment workers are determined upon a reduction in the work week from 44 to 40 hours. Organized labor knows that every improvement in hours, wages and better working conditions has been wrung from hostile employers thru the weapon of the strike.

The battle of the dye workers of Passaic is the battle of organized labor throughout the country. It is a heroic struggle against ruthless exploitation, and disregard of human life. It is a splendid challenge to the employing interests that workers refuse any longer to be treated as so much raw material to be utilized with dyes and acids for the profits of the mill owners.

The medical findings among the 77 dye workers examined were compared to the following studies previously made:

Dr. Emery R. Hayhurst: Study of 267 Painters examined by the Workers’ Health Bureau—1923.

Dr. Louis I. Harris: “A Clinical & Sanitary Survey of the Fur and Hatters Trade, N. Y. Dept. of Health—October, 1915.

“The Health of Food Handlers”, L. I. Harris & L. L Dublin—1917.

Report on the Examination of 1,044 Printers, Dr. L. ¢, Harris—1923.

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v16n06-jun-1927-LA.pdf