Aaron Copland, in his Communist years, takes a look at the efforts of the Workers’ Music League and the publication of their first songbook.

‘Workers Sing!’ by Aaron Copland from New Masses. Vol. 11 No. 10. June 5, 1934.

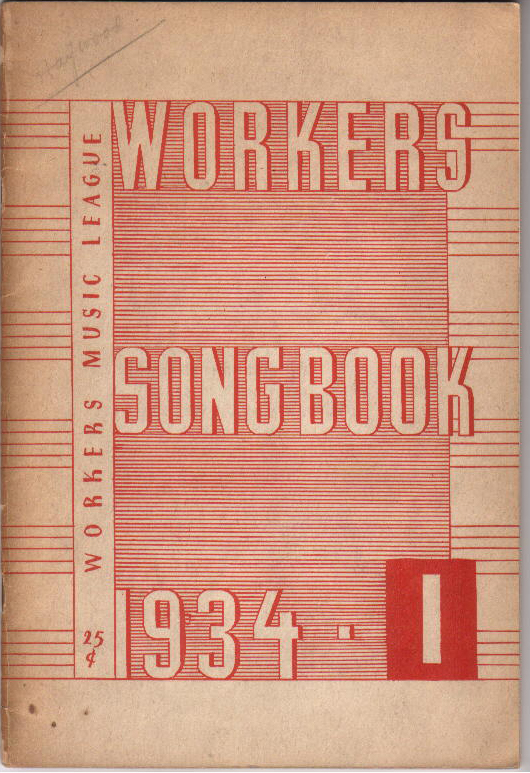

THE Workers’ Music League, a branch of the International Music Bureau, has recently issued the first adequate collection of revolutionary songs for American workers. According to its foreword, the Workers’ Song Book 1934 is made up “exclusively of original revolutionary mass, choral and solo songs with English texts, (the first to be made in America). The composers represented are members of the Composers’ Collective of the Pierre Degeyter Club of New Yark City, an affiliate of the Workers’ Music League. With three exceptions the songs were all composed in 1933 as part of the work of the Collective.”

Every participant in revolutionary activity knows from his own experience that a good mass song is a powerful weapon in the class struggle. It creates solidarity and inspires action. No other form of collective art activity exerts so far-reaching and all-pervading an influence. The song the mass itself sings is a cultural symbol which helps to give continuity to the day-to-day struggle of the proletariat.

To write a fine mass song is a challenge to every composer. It gives him a first-line position on the cultural front, for in the mass song he possesses a more effective weapon than any in the hands of the novelist, painter or even playwright. As more and more composers identify themselves with the workers’ cause, the challenge of the mass song will more surely be met.

Composers will ask: “what is a good mass song”? In answering this question we must not forget that the opinion of the trained musician will not always coincide with that of the masses. We as musicians will naturally listen to these songs primarily as music, but the workers who sing them will in the first instance decide how they apply to the actualities of the daily struggle. In their eyes the music will not necessarily be of primary importance; if the spirit is right, and the words are right, any music will suffice which does not “get in the way.” Composers will want to raise the musical level of the masses, but they must also be ready to learn from them what species of song is most apposite to the revolutionary task.

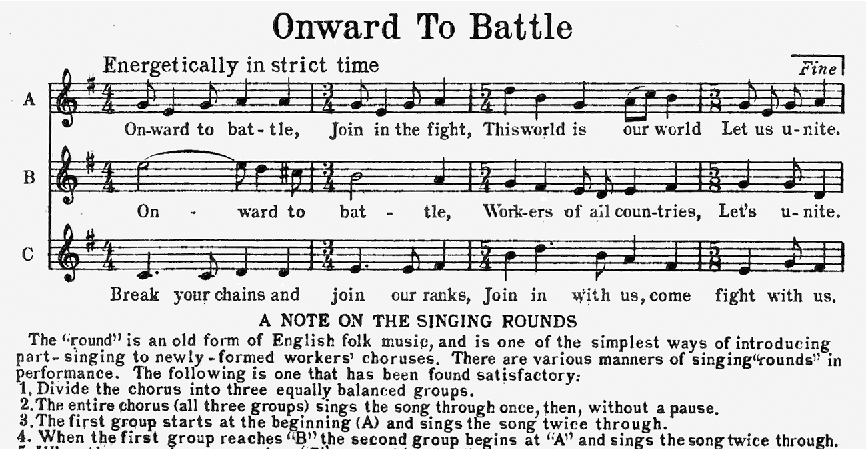

A good case in point, taken from this first book of American workers’ songs, is that of The Scottsboro Boys Shall Not Die with words by Abron and music by L. E. Swift. This is the only song in the volume which has already been repeatedly sung by large masses of workers, yet judged from a purely musical standpoint it is certainly not the best song in the collection. The explanation is simple. The issue of the Scottsboro Boys is close to the hearts of class-conscious workers; to these workers the fact that the text of the song does not constitute great poetry, and that the music is effective only in a rather flat-footed and unimaginative fashion is of secondary significance. Nevertheless musicians must continue to insist that the music be of the finest calibre, not for “esthetic” reasons alone, but because a better musical setting will make a song a more thrilling experience and thereby increase its political drive. Swift himself has written better songs musically in the “Three Workers’ Rounds”: Poor Mr. Morgan, Red Election, and Onward to Battle, built on an old form of English folk music. Yet these have not taken hold. Our conclusion should be that a first rate mass song must be satisfying in text and music to both worker and musician.

On the whole, Carl Sands seems to me to have written the best songs in this present collection. In various ways his work can serve as a model for future proletarian composers. Mount the Barricades is an excellent mass song with a simple musical line and unconventional harmonies; Song of the Builders for chorus with piano accompaniment has rhythmic variety plus a natural setting of the words; Who’s That Guy is an amusing kind of “play-song” intended for use with dramatic action. These may not be great songs, but they display a directness of attack and a sure technical grasp which is refreshing.

The songs of Lahn Adohmyan included in this volume are more ambitious. Adohmyan tries for a revolutionary content through use of a revolutionary musical technique. He is not afraid of harsh harmonies and a jagged voice line. These things need careful handling if they are not to result in music which is ungrateful for performers and unrewarding for listeners. Judging from Adohmyan’s elaborate a capella choral setting of Joseph Freeman’s poem Red Soldiers Singing and from the mass Song to the Soldier one would say that the composer is not always as careful in these matters as he should be. This is the more to be regretted because Adohmyan’s music possesses real vitality and a character of its own. It is to be expected, however, that as he matures, the aspect of his music which does not allow it quite to “come off,” will be overcome. Already he is outstanding among the younger proletarian composers.

Jacob Schaeffer, the radical movement’s veteran choral conductor and composer, presents a different problem in his three songs Hunger March, Strife Song and Lenin, Our Leader. It is this: can a composer use the musical speech of the nineteenth century to express revolutionary sentiments? One thing is certain: we cannot ask Schaeffer to write in an idiom which is not his own. And it is only natural that, belonging to an older generation, his musical speech will not be as “up-to-date” as that of his younger fellow-composers. But whatever the idiom used, we can demand revolutionary music that is first-rate in quality.

Schaeffer’s compositions, however you look at them, seem unnecessarily conventional in spirit. This basic conventionality is sometimes made even more glaring by what would appear to be a conscious attempt on the composer’s part to be “modern.” He is at an added disadvantage in this collection because his songs are translated from the Yiddish. This almost always produces stiff and unnatural prosody. The Hunger March, for example, deserves a better translation, for it is a straight-forward and effective mass song that shows Schaeffer at his best, which is when he is simplest.

Of the fourteen songs in this volume only four are, strictly speaking, mass songs. There should be more. The rest are revolutionary choral compositions written for performance by trained workers’ choruses and solo songs intended for concert performance. (Of the latter group, God to the Hungry Child by Janet Barnes is immature and might well have been omitted.) These various categories obviously do not belong together, and in later editions, when there are more songs of each type, it would be wise to issue them in separate collections. Also, one would like, to see a larger number of composers represented in the collection.

Those of us who wish to see music play its part in the workers’ struggle for a new world order, owe a vote of thanks to the Composers’ Collective for making an auspicious start in the right direction.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s to early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway, Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and more journalistic in its tone.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1934/v11n10-jun-05-1934-NM.pdf