Stimulating reflections from Louis C. Fraina, founder of U.S. Communism, on nation building and nationality penned during the First World War.

‘The Problem of Nationality’ by Louis C. Fraina from The New Review. Vol. 3 No. 18. December 1, 1915.

I.

THE problem of Nationality cannot be considered simply in its relation to the right of nations to independence. It is primarily a problem in the history and economics of Capitalism, the problem involved in the stage of development achieved by the social-economic system contained in a nation, and which determines the form of expression of the nation.

Nationality does not come into being because of mystical or cultural impulses; it is created by a definite process of economic development and its political reflex. Nationality is not desirable in itself; it is desirable only as a tool with which to work at particular stages of our social development. Nor is Nationality in itself democratic and progressive; it is that only when the social forces it expresses trend toward democracy and progress; under different circumstances Nationality may be completely reactionary.

A very important point to be stressed in a discussion of Nationality, accordingly, is the fundamental difference between the democratic nationalism of the era of bourgeois revolution and the reactionary nationalism of Imperialistic capitalism. Eduard Bernstein proposes that Socialists oppose only the “new capitalistic nationalism which culminates in Imperialism,” and not the “old ideology” of nationalism “which required the self-government of the nation as a centre of culture among other similar centres.” Bernstein’s proposal neglects seriously the economic and political aspects of the problem, as determined by the development of capitalist Imperialism and its reactionary tendencies. It is impossible to revive the old democratic ideology of nationalism, since the social conditions underlying its previous existence are no longer dominant in the economy of industrially highly-developed nations. The emphasis laid upon democratic nationalism leaves unconsidered the fact that capitalism has turned its back upon the era of its democratic aspirations, and that consequently the contemporary expression of Nationality is un-democratic.

Nationalism, as much as Imperialism, possesses general characteristics; but to discuss the problem of Nationality in its general characteristics alone is to miss its real significance. While the essential economic characteristic of Imperialism is the export of capital, each national Imperialism has its own distinctive features determined by economic and political development. The essential characteristic of Nationality is the temporary necessity of the nation as a centre of economic, political and cultural activity; but the form of expression of Nationality varies as the historical requirements vary. Not only is Nationality to-day different in the great capitalist nations from the Nationality of the era of bourgeois revolution, but Nationality differs as between different nations, and nations in process of formation.

These differences are not simply theoretical in their interest. Important practical conclusions are involved. They signify that new social forces have come into being, fundamentally altering the problem and our attitude toward the problem. The change from Colonialism to Imperialism means not simple change in the foreign policy of nations, but change in the economics of Capitalism, a new stage in economic development. The problem of Nationality in its newer aspects has a similar meaning directly determined by the Imperialistic trend.

The newer Nationalism, in its Imperialistic aspects, demonstrates that the Great War is not result of Nationality as much as a revolt against Nationality. Although there is a peculiar circumstance involved: that this revolt against Nationality proceeds along nationalistic lines, the effort of particular nation to subjugate other nations in its own national interest. But in spite of its dynamic expression, it is fundamentally conditioned by the economic urge which seeks to shatter the fetters of Nationality. Industry organized along national lines has become an obstacle to the development of the forces of production; industry has become international to a point where it must tear down the barrier of the nation.

II.

Nationality, the trend toward Nationality, makes its appearance simultaneously with Capitalism. Ascending capitalism develops the nation-state, which plays an important part in the overthrow of feudalism and the establishment of the capitalist economy. The effort to break the fetters placed upon industry organized on the basis of the city-state leads directly to the formation of the modern nation. Ascending capitalism requires freedom of trade with, in as large a territorial unit as possible, national markets exclusively for the national bourgeoisie to develop and exploit; a common system of coinage, weights and measures; and a strong central government to protect and encourage capital, and to carve out larger territorial limits for the nation. The nation-state develops a sense of solidarity in the people of a particular national group, and firmly establishes national institutions, a national literature and culture. The nation has conformed essentially to economic and geographical facts; while race and language have been convenient expressions of Nationality, the nation has itself created “race” and “language”, and often suppressed them in the fulfillment of its historic task.

The early struggles of ascending capitalism seek to create the national unit along as large territorial limits as possible, while maintaining order within the national domain. The industrialized unit in the nation seeks wider markets, wider sour es of raw material, -regions which it can industrially revolutionize. The process of expansion is accelerated by a series of bloody wars. All this, in conjunction with other favoring circumstances, leads to the institution of absolute monarchy, directly traceable to the requirements of the bourgeoisie. The bourgeoisie at this period is only slightly revolutionary, its revolutionary expression assuming vitality in the measure that the task of carving out the national frontier is completed. But, this task accomplished, the social organization expressed in the dominance of absolute monarchy, itself based upon a compromise between the bourgeoisie and the feudal nobility, becomes a very real obstacle to the development of the productive forces. In the efforts to destroy this obstacle the bourgeoisie initiates its revolutionary era, on result of which is the organization of the nation along democratic and republican lines. It is at this epoch that the nation assumes a definite and concrete form. (1)

But the bourgeoisie becomes frightened of its own revolutionary impulses: all bourgeois revolutions end in dictatorship, -which persist or disintegrate as conditions determine. (2) Having accomplished the task of destroying the economic fetters upon its development, the bourgeoisie becomes indifferent to the form of government, as long as scope is allowed its economic development. Fear of the proletariat, competition between nations, struggles between various groups of the ruling class itself, immaturity of governmental experience,-all these circumstances incline the bourgeoisie toward “strong” government, leaving a merely sentimental feeling for general liberal principles. A compromise is struck in constitutional monarchy.

In this process of developing the nation, revolution and liberal ideas are merely an incidence. When the bourgeoisie has completed the industrial revolution, it discards its liberal ideas and retains only that irreducible minimum necessary for social control. This minimum varies as the historical requirements vary.

In nations which completed their national bourgeois revolution sufficiently prior to the era of modern Imperialism to allow their democratic ideas scope for ascendancy, the reaction against liberal ideas was only partly successful; finally working itself out in a republic -as in France- or an essentially democratic government -as in “monarchical” England. But in nations which completed their national revolution almost simultaneously with the advent of Imperialism, democracy in government never established itself. Germany is the classic type of this new development, with Japan a remarkably close parallel.

The bourgeois revolution in Germany in 1848 was crushed by the terrific blows of the counter-revolution. National unity was achieved not as a revolt against the feudal class, but with the feudal class of Junkers in control. Bourgeois democracy remained a thing of the future. The industrial revolution in Germany strengthened, instead of weakening, the monarchical power. It is fashionable to attribute this development to “Prussia,” or to Treitschke and the peculiarities of the German people. But the reaction, as at previous periods, might have proven temporary (the forces of democracy grew steadily, a whole movement- the Social Democracy- being devoted to the task of completing the bourgeois revolution) had not a new set of circumstances intervened which, instead of finding its interest in the overthrow of monarchical power, found its interest in its perpetuation, -the advent of Imperialism.

It is not our task at the present moment to discuss the basis of Imperialism, its relation to the economics of capitalism. It is sufficient for our requirements to point out that Imperialism assumes the political form of a struggle for the control of territory rich in natural resources and capable of being industrially revolutionized by the industrialized nation undertaking the work of “development.” Capitalism in its Imperialistic phase turns in on itself and reproduces the period of its youth, when it struggled for a similar objective, -with this difference, however: that where the earlier struggle created Nationality, the contemporary struggle for undeveloped territory negates Nationality. This process carries with it a corollary: as the earlier struggles of capitalism produced war and monarchy, so to-day Imperialism not alone produces war but a tendency toward “strong” government, -monarchy disguised under a variety of political forms. (3)

Germany was united in 1871; and fifteen years later its Imperialistic era began. This let loose all those reactionary tendencies which lead to a revival of monarchical power. The democratic movement gradually turned Imperialistic, and even the Social Democracy became subtly nationalized, until when it expressed its nationalism at the outbreak of war it suddenly discovered that its nationalistic position committed it to Imperialism.

German Imperialism rejects the principle of Nationality. The conquest of nations is its political objective, war the medium through which it works. The feudal military caste and the imperial regime are accepted as means for the prosecution of war and aggression.

The negation of Nationality is not peculiar to German Imperialism; it is an attribute of all Imperialism. An Italian Imperialist declaims as follows: “It remains for us to conquer. It is said that all the other territories are ‘occupied.’ But there have never been any territories res nullius. Strong nations, or nations on the path of progress, conquer nations in decadence.”

A peculiarity of Italian Imperialism, which distinguishes it from other Imperialisms, is that, while in Germany Imperialism is distinct from nationalism -Imperialism transforming and identifying itself with nationalism in order to secure a popular sanction for its purpose-in Italy Imperialism and nationalism developed simultaneously and are really a common movement. This is because Italy was not fully created a nation by its bourgeois revolution. While Italy was created a national state half a century ago, it was not until some decades ago that a real national sentiment began to animate the country. Nationalism and Imperialism developed simultaneously, and merged into one. (4)

Imperialism, accordingly, is the negation of Nationality because the barriers of the nation are no longer compatible with the development of the forces of production. Imperialism seeks to break down these barriers by means of one nation dominating other nations. The Socialist solution is not to emphasize Nationality, but democratic Federalism. the submergence of Nationality in a federal union of the nations, based upon economic necessity, and organized along democratic lines.

III.

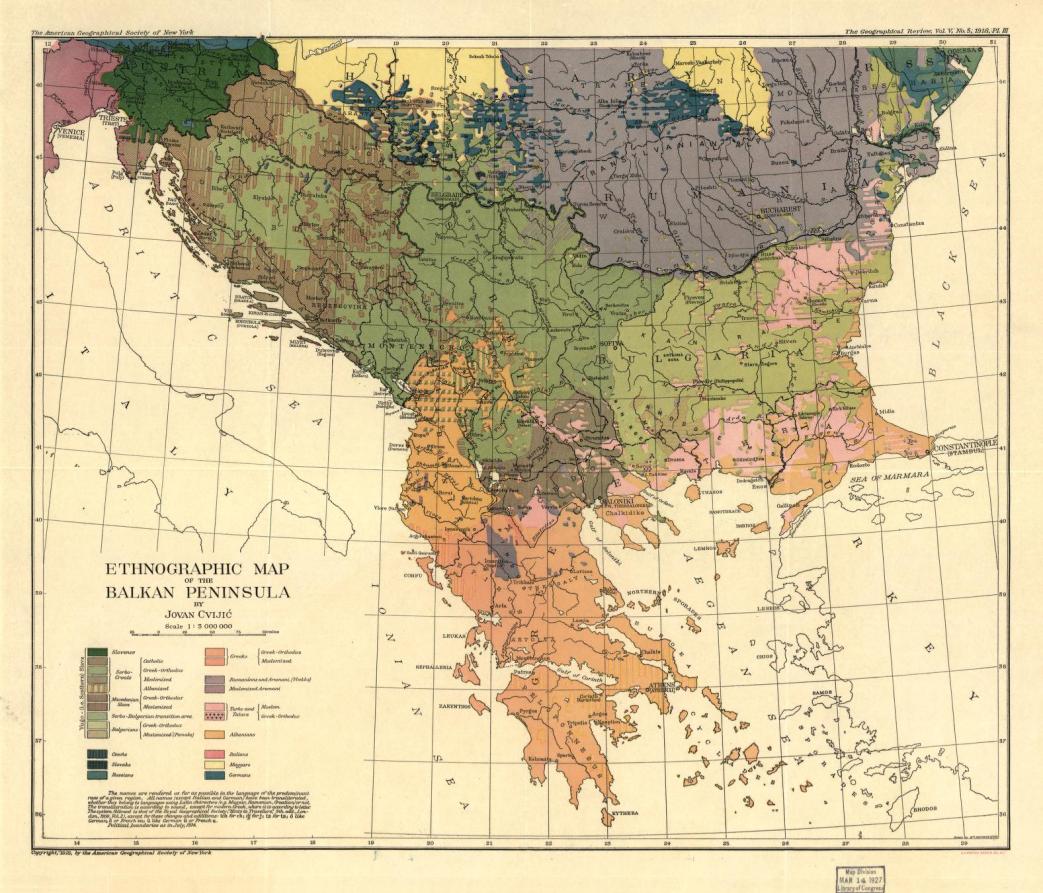

The spirit of the demand for new national groupings in Europe is just; but the literal fulfillment of the demand would emphasize national divisions, create new barriers to the expansive forces of Capitalism provocative of war, and doom certain nations to a precarious economic existence.

A stimulating study of the practical aspects of Nationality is contained in Arnold J. Toynbee’s Nationality and the War. (5) It is a really excellent book in material, scope and treatment, -the only adequate study extant of Nationality in its modern European aspects as a practical problem in national groupings.

Toynbee starts out with a fundamental error, which vitiates much of his theoretical discussion, but does not affect- strangely- his practical conclusions. This error is that Nationality in itself is the cause of the war. It is an error, however, which is only partly an error; for Toynbee has in mind the eastern field of the war, where the national aspirations of the Balkans led directly to the present war. But this is only a minor phase of the war; the nation al problems of South-Eastern Europe may be fully solved, but that would not end the struggle between Alliance and Entente, it would simply give it a new expression.

Toynbee’s general conclusion is:

“The first step toward internationalism is not to flout the problems of Nationality, but to solve them.”

How? By accepting-

“The principle that the recognition of Nationality is the necessary foundation for European peace.” But in the course of his analysis, Toynbee is compelled to recognize the potency of economics, and substantially modifies his conclusion:

“We have to devise a new frontier which shall do more justice than the present national distribution, without running violently counter to economic facts.” Again: “Will the centripetal force of economics fin ally overcome the centrifugal force of Nationality?” Toynbee emphasizes that in the process of creating Nationality, of securing access to the sea, raw material and wider markets, Nationality is partly suppressed:

“The Hungarians used the liberty they won in 1867 to subject the Slavonic population between themselves and the sea, and prevent its union with the free principality of Serbia of the same Slavonic Nationality. This drove Serbia in 1912 to follow Hungary’s example by seizing the coast of the non-Slavonic Albanians; and when Austria-Hungary prevented this (a righteous act prompted by most unrighteous motives), Serbia fought an unjust war with Bulgaria and subjected a large Bulgarian population, in order to gain access to the only seaboard left her, the friendly Greek port of Salonika.”

The way in which economics dominates Nationality is attested by the Austro-Hungarian Ausgleich, the compromise by which Austria and Hungary maintain their unity, while each national group is allowed autonomy. The reason for this is economic: “The Ausgleich is simply the political expression of the economic situation. The Austrian half of the Dual Monarchy corresponds to the industrial region above Vienna, the Hungarian half to the agrarian region below it. Their economic interdependence is recognized in the common tariff: Hungary abandons the possibility of building up an indigenous industry of her own, by protection against Austrian manufacturers, in order to secure a virtual monopoly of the Austrian market for foodstuffs and raw produce.”

Toynbee clinches his analysis with a plea for federated nationality:

“The national atom proved less and less capable of adoption as the political unit. In Central Europe, the Tchechs will be unable to work out their national salvation as an independent state: the economic factor necessitates their political incorporation in the German Empire. In the Balkans the political disentanglement of one nationality from another is only possible if all alike consent to economic federation in a general zollverein. In the North-East, geographical conditions decree that national individuality shall express itself by devolution within the bond of the Russian Empire. (6)

“In all cases the political unit reveals itself not as a single nation but as a group of nationalities; yet even these groups cannot be entirely sovereign or self-contained. Like the chemist’s molecules, they are woven out of relations between atoms, and are bound in their turn to enter into relation with one another. “The nationalities of the South-East coalesce in a Balkan Zollverein; the Zollverein as a whole is involved by mutual economic interests with its neighbor molecule, the Russian Empire; similar necessity produces similar contact between the Russian Empire and Norway or Persia. The simple uni-national molecules of the West and the complex multinational molecules of the East and Centre all dispose themselves as parts of a wider organism- the European system.”

The practical problem is no longer simply one of Nationality, but of economics plus democracy, -the democratic, autonomous federation of nationalities and nations. The process of capitalist development which created the nation at the same time created it as an economic unit. A nation must be an economic unit, otherwise it cannot survive. Virtually none of the subject nationalities in Europe can create a nation economically self-sufficient. The problem solved itself if democratically approached.

The larger practical aspects are clear: Insofar as Europe is concerned, democratic federalism is the only alternative to Imperialism, -the only democratic, peaceful and civilized way of solving the economic problem involved in Imperialism. But the problem alters itself in non-European countries struggling for Nationality. In China and Mexico, for example, the problem must temporarily be solved along strictly national lines,- the development of a national capitalism, national government and institutions. And this suggests the great problem of the near future: granting that Europe federates, may not federated Europe crush these backward nations? The new Socialist international must meet this problem with an uncompromising demand for national self-government of these peoples. The revolutionary proletariat alone can compel the democratic federation of the nations of Europe and the ultimate federation of the world.

NOTES.

1) It is interesting to note, that the French Revolution, the finest expression of the revolutionary bourgeois era, was compelled by the struggle against practically all of feudal Europe to break through the boundaries of Nationality and project an internationalism implicit in the concept of cosmopolitan republicanism. But both the internationalism and the revolutionary ideology were discarded as economic organization proceeded along national lines.

2) This statement does not require corroborative details, bearing Cromwell and Napoleon in mind. General Washington was offered a crown, and there was a strong party with decided monarchical tendencies in the first days of our republic. The recent bourgeois revolution in China ended in dictatorship.

3) This tendency toward “strong” government is a general phenomenon. In this country it is quite obvious. Imperialism Is not the only factor in the process. The deeper economic cause, which in itself is a great contributing factor toward the rise of Imperialism, is the dominance of great capital and the decay of the middle class as an independent class. In this country the Bryan movement represented the revolt of the middle class, the Roosevelt progressive movement the attempt of this class to strike a compromise with plutocracy. This means the abandonment of the middle class, the historical carrier of liberal ideas, of its liberalism, directly leading to the “strong” government or State Socialism.

4) Russia seems on the verge of a similar development. “It (the bourgeoisie) might get along for a couple of years with the aid of internal reform, especially in agriculture, without further expansion in Asia; that is, through such reforms the development of the internal market might be greatly increased. But internal reforms demand the overthrow of Czarism and the abolition of all pre-capitalistic plundering. The Russian bourgeoisie is afraid of the struggle, and so allies itself with Czarism, and strives for new conquests in the East and South.” Paul Axelrod. New Review, January, 1916.

5) Nationality and the War, by Arnold J. Toynbee, New York: B. P. Dutton & Co.

6) Toynbee says about Poland: “The majority of the Polish nation under Russian rule has actually benefitted economically by its subjection, and economics have gone far towards settling the political destinies of the whole reunited Poland, for whose creation we now hope. Even her eighteen millions cannot stand by themselves, with no coastline and no physical frontiers. She must go into partnership with one of her larger neighbors.”

New Review was a New York-based, explicitly Marxist, sometimes weekly/sometimes monthly theoretical journal begun in 1913 and was an important vehicle for left discussion in the period before World War One. In the world of the Socialist Party, it included Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Herman Simpson, Louis Boudin, William English Walling, Moses Oppenheimer, Walter Lippmann, William Bohn, Frank Bohn, John Spargo, Austin Lewis, WEB DuBois, Maurice Blumlein, Anton Pannekoek, Elsie Clews Parsons, and Isaac Hourwich as editors and contributors. Louis Fraina played an increasing role from 1914 on, leading the journal in a leftward direction as New Review addressed many of the leading international questions facing Marxists. The journal folded in June, 1916 for financial reasons. Its issues are a formidable archive of pre-war US Marxist and Socialist discussion.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/newreview/1915/v3n18-dec-01-1915.pdf