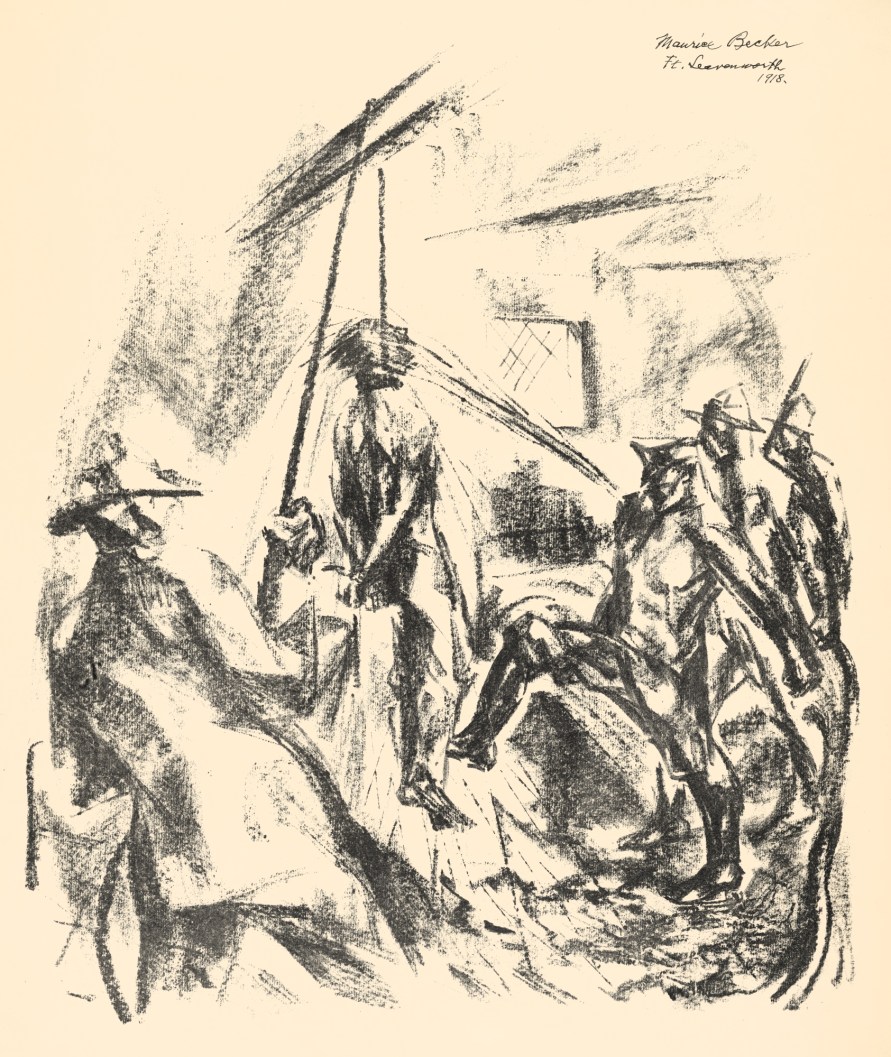

Torture, political classes, secret messages, contraband literature, and prison strikes. An amazing piece of revolutionary U.S. working class history. H. Austin Simons writes from Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary on the organizing and prison life of hundreds radicals imprisoned for opposing World War War One and the capitalist system which spawned it.

‘The U.S. Revolutionary Training Institute’ by H. Austin Simons from The Liberator. Vol. 2 No. 9. September, 1919.

FORT LEAVENWORTH during the last two years has become the little Siberia of America. The most obvious comparison is between the treatment administered to prisoners in the Czar’s prison camps and the handling of American young men by American soldiers in this American military prison. The most subtle resemblance between our prison and those in Siberia is in the atmosphere of “underground” that prevails in both places…

At the time of the prisoners’ strike, last February, the main group of objectors, numbering about 150, was in the seventh wing, an open-cell unit, an “honor wing,” in which ordinarily no sentries were on guard and where we had freedom to move about the entire corridor. It was there that the first actual organization took place.

After our refusal to work, we were sent back to the cell house. As I was starting up the tiers toward my cell, one of the “hard guys” called to me:

“Hey, sixty-one, if we’re goin’ to have a strike, we gotta find out what we’re strikin’ fer an’ what we’re goin’ to do.”

“You’re right,” I said. “Organize!”

“We gotta have a meetin’ an’ speeches.”

“Well, if you and the other fellows feel that way about it,’ I said, “get the men together tonight and Tl talk to them.”

“But we oughta have it right now, before these zibs get a chance to scab.”

“All right,” I agreed, “but how about the screws?” — referring to the sentries who were coming into honorwings during those troublous times.

“We’ll give you protection. Go to it.”

So we went to the rear of the wing and held the first meeting of the strike. I stood on a bench and talked to about 250 men who crowded around the bench on which I stood, closely, so that their heads concealed the numbers painted in white across each leg on my trousers. Whenever guards entered the wing, a lookout rang the gong, I stepped down from the bench and lost my identity in the mass of ugly uniforms. When the soldiers departed we resumed the meeting…These are simple wiles of the underworld. By such means the “seventh wing soviet” was organized secretly and was prepared to lead the whole prison-body next day when the officers agreed to meet a general committee…

But the most significant similarity between the Fort Leavenworth military penitentiary and the Siberian places of isolation is that both have been schools for revolution…

Maybe it was Secretary Baker’s enlightened liberalism or it may have been an indication of the present administration’s naive faith that it can alter a thing merely by changing its name that led to the official statement that the Disciplinary Barracks should not be regarded as a military prison, but should be called the “U.S. Vocational Training Institute.” The objectors were the only ones who took that announcement seriously. The only vocation they studied was the technique of rebellion.

We did not despair when we found ourselves for the first time in cells, with “box car numbers” painted across our thighs and between our shoulders. We refused to consider ourselves “buried alive” or even confronted by a number of years of lost youth. The reason why we were able to maintain this point-of-view without becoming bitter or vindictive is to be found in the pleasure and the sustaining comradeship we discovered through our joint intellectual activities.

Our first request of the officers was for books; our constant fight was for magazines. We got some through authorized channels; others we obtained by underground. In one way or another we got THE LIBERATOR nearly every month. We also managed to get many of the classic books and pamphlets on Socialism. Once a political objector, showed me a small volume bound in black, on the cover of which was stamped, in silver letters, “New Testament.”

“Look inside,” the comrade said.

I did so, and found not a page of “scripture,” but the entire Communist Manifesto. It had been smuggled in and had been rebound by a prisoner in the printshop. It may seem extraordinary that such a thing could be done in a prison printing-plant; it will appear less impossible when it is known that other prisoners working there printed and forged government checks and vouchers to the amount of $60,000.

But we were anxious to co-ordinate our studies and to use systematically the educational talent among us. So we began, early last winter, to hold evening classes in Billy Treseler’s cell on the fourth tier of the seventh wing.

The instructor sat on a stool and the students crowded about on the “double-deck” bunk, the concrete floor, and the tier-railing outside. Soon the number of pupils became too great for this small space. So we arranged benches and a table in one corner of the main floor of the wing and made that our classroom. Others besides objectors came to listen. General prisoners from different wings took the risk of trial by the executive officer to’ come to the lectures and discussions. The corner-classroom was crowded at every session and dozens of men sat on the tiers above, listening. We were able to do all this because we objectors were popular among the other prisoners, because no sentries were in that cell-unit and because no cells there were locked.

Allen Strong Broms, a Socialist from St. Paul, Minn., who in 1917 was, next to Victor Berger, the most indicted citizen of the United States, taught the first classes. He had been an office engineer for a railroad corporation in civil life; he gave us a course in “Efficiency in Propaganda.” He also had been a lecturer on sociology; so we arranged a second class for him and he gave lectures on these subjects: “Is a Science of Sociology Possible?” “Sociology Among the Sciences,” “The Idea of Evolution in Sociology,” “The Socialist Contribution to Sociology,” “Sociology and Political Economy,” and “The Making of Progress.”

Meantime, Carl Haessler, Ph.D., Oxford graduate, instructor at the University of Illinois, had come to prison. The very fact of his presence was dynamic; it changed the aspect of many things…I was the fifth objector to arrive at Fort Leavenworth. For months there were less than fifty of us and most of those, young and unknown. I felt keenly the apparent failure of the anti-draft movement, its lack of large numbers, the absence from it of great personalities. Then, one Saturday noon at mess, a comrade who worked in the executive office, said to me, “Dr. Carl Haessler was ‘dressed into numbers’ this morning. He wants to see you in your cell right after mess.”

I was excited at that prospect; but marching out of the mess-hall I met for the first time Clark Getts, who later was secretary of the prisoners’ strike committee. Getts was known as the most handsome and the most popular man in the jail, one of the most effective spokesmen of the movement and the most active man in prison politics and prison propaganda. One of the hard-guys, speaking of him to me, said:

“You know, there’s a geek I just can’t help likin’. I may not believe w’at he t’inks, but I ceuldn’t dislike ‘im if I wanted to…”

When I left Getts I hurried into my cell and found Haessler lying on my bunk, already discussing ideas with a crowd about him. As I listened to him tell of his fight against the reactionary elements in the Harvester Trust’s state university at Urbana, Ill., of his work as a journalist and propagandist in Milwaukee, and prison anecdotes which incidentally revealed his courage and shrewdness at every encounter with military officers, my doubts of our movement disappeared. At last, the conspicuously competent leader had come…

Haessler soon was acknowledged the intellectual leader of the objectors, not by themselves alone but by the officers as well. At one of the innumerable psychological examinations to which we prisoners were subjected, Haessler (who in camp had obtained a higher mental rating than any other person in the National Army) was examined by a “shavetail.”

“How long did you go to school?” the lieutenant asked.

“Twenty-two years.”

“What was the reason for your quitting?”

Adopting the prisoners’ favorite phrase, Haessler replied, “Why, there hain’t no more.”

That first afternoon in my cell, Haessler read Plato to us. So greatly we enjoyed it that thereafter we often listened to him read and discuss the Greek philosophers, and Freud, and the pragmatists. When Broms’ courses were done, we arranged a series of lectures by Haessler on pragmatism- “Illusions of Progress” in civilization, religion, knowledge, morality, truth.

When we were segregated in “Wire City,” the small stockade adjoining the prison proper, we started a night school with the following program:

Monday, philosophy, taught by Haessler; Tuesday, English composition, by Simons; Wednesday, Marxian economics, by Carlten Rudolf; Thursday, logic, by Haessler; Friday, biology, by Getts and Schieder. This school continued until the transfer on June 18 of five members of its faculty to Alcatraz Isle, San Francisco harbor.

Out of our intellectual desires and our delight in frustrating official attempts at suppression, arose other activities. The prison-censor prohibited Bertrand Rusell’s “Four Roads to Freedom.” In consequence we held “a symposium on social, economic and industrial movements of today.” Otto Wangerin of St. Paul defined socialism; Broms, collectivism; Haessler, syndicalism; Simons, anarchism, and a dozen other fellows participated in discussion that followed. Thereafter on Sunday nights symposiums were the regular things.

To spread Bolshevism, and to practice the technique of agitation, we held open street-curb meetings; mounting benches, drawing in crowds, manipulating applause, expounding industrial unionism, the theories of socialism and the soviet system of government.

We celebrated revolutionary occasions. The first such meeting was held March 9, in observance of the second anniversary of the Russian revolution. Openly, in defiance of sentries and “rats” or stool-pigeons, we gathered in the rear of the wing and reviewed the history of the revolutionary movement in Russia, discussed deportations of radical aliens and prophesied the advent of the proletarian dictatorship in America. With heads uncovered we sang the funeral march that had sounded through the streets of Moscow at the “red burial.” We filled the prison with the music of “The Black Standard.”

…We observed May Day and the birth anniversary of Karl Marx. We had a Whitman Day program instead of attending the Memorial Day ceremonies presided over by the chaplain…

But what was the result of this constant activity?

Did we affect the prison?

In innumerable ways, yes. Leading the other prisoners, the “conscienceless” objectors – the red ones- created a sort of jail-democracy, a prison-bolshevism. By frequently, fearlessly enduring solitary confinement, by forcing the War Department to abolish the practice of shackling prisoners to the bars, we largely demoralized the discipline that had been imposed upon all prisoners. As a result of the strike which we led, we established a prisoners’ committee which now superintends sending the gangs to work, which has charge of the discipline in the cell-wings, the mess-hall and the yard, and which tries all cases of breaches of rules, except those under the jurisdiction of general court-martial.

We gained scores of converts among the prisoners. One fellow asked me, shortly before my release, “Hey, sixty-one, do youse Bullsheviski need any box-fighters or blackjack-men in the movement?”

“There’s a place for everyone in the movement,” I replied.”

“Well, youse guys can count me in! I’m a Bullsheviski from now on. I been talkin’ to some o’ your gang an’ I see now where I got a dirty deal an’ where we all get a dirty deal an’ how it’s all the fault o’ the system an’ we’ got to change the whole damn’ thing.”

He wanted to know how it should be changed. We taught him. He’s reading proletarian papers now.

My “buddy” in the Disciplinary Barracks was a fellow from the Air Service Flying School, Fort Worth, Texas, who had been convicted on charges preferred by an officer whom he had rivalled in a love-affair. Soon after he came to prison he came in contact with our group. Wetook him in. Several months later he was called before the officer in charge of the disciplinary battalion.

“Do you want to be restored to duty?” the Major asked.

“No, sir.”

“Why not? I should think that, with this sort of charge against you, you’d be glad for a chance to be restored to the status of honorable duty.”

“Thank you, sir. But I’m done with Uncle Sam and his army!”

“What do you mean? Are you a c.o.?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Why, you’re not listed as one.”

“I know it, sir. I didn’t come in here as one, but I’m going out as one!”

He did. His sentence of one year expired in July and he came to Chicago to study the movement and to find a place in it.

We reached the guards, too, with our propaganda. Shortly after the strike I was seated in the mess-hall next to the aisle. I noticed a soldier standing by me but paid no attention to him, thinking that he was inspecting the table or the food. Presently I heard him whisper:

“Don’t look up. Don’t recognize me. You’re Simons; I know you by your number. My name is J—. And I’ve wanted to say to you that I’m for you and Haessler and Getts. And I’m not the only one; you fellows have some real comrades in the guard-companies…”

And we ourselves underwent great changes. I do not know about the religious c.o.’s; but of the majority of the politicals I do know that we were confirmed and determined as revolutionaries by our experience in prison, as many leaders of the movement in Europe were influenced by their earlier sentences to exile. Those who had been “parlor radicals” planned to join one or more actually revolutionary organizations upon their release; those who had been active before going to prison were resolved to devote themselves entirely to the movement. No better can this devotion to a single cause be realized than by knowing the changed attitude of the men in this group toward amnesty. In the last issue of the “Wire City Weekly,” the typewritten magazine we published surreptitiously, this statement appeared:

“The motto of the objectors is no longer ‘We want amnesty.!’ It is ‘We want revolution!'”

The night before Allen Broms was released, we held a farewell meeting and the spirit of the men was expressed in such words as these:

“You, comrade, are fortunate enough to go out before the rest of us go. We want you to be our emissary from this underworld to those comrades and sympathizers on the outside who can help us. Urge them to work for the freedom of us all. Do not forget us who still are in numbered uniforms.”

The last farewell gathering I attended was on the night before my own departure. We were in the fourth wing basement then, with sentries guarding us. We waited until lights were out and the soldiers had withdrawn to the far end of the dim corridor; then the fellows came and sat on my bunk and on the cots around it. Speaking almost in whispers, they gave me this message to the outside:

“Of course, we want our freedom. We believe that the time for amnesty is present. But that is not the great thing. Tell the comrades to work for The Revolution.

“For ourselves, our only hope is that the fact of our imprisonment may abet the movement. For that fact is a challenge to American liberalism. If the ‘liberal’ president does not accept the challenge, his liberal followers must do so for their own integrity. When they do so, they will find themselves forced into radicalism. Thus, it is for our comrades on the outside to justify our imprisonment by propaganda, as well as to end it as soon as may be.”

And then, in a murmur that rose and fell and died away like a little wind in the night, they sang,

“Though cowards flinch and traitors sneer,

We’ll keep the red flag flying here.”

The Liberator was published monthly from 1918, first established by Max Eastman and his sister Crystal Eastman continuing The Masses, was shut down by the US Government during World War One. Like The Masses, The Liberator contained some of the best radical journalism of its, or any, day. It combined political coverage with the arts, culture, and a commitment to revolutionary politics. Increasingly, The Liberator oriented to the Communist movement and by late 1922 was a de facto publication of the Party. In 1924, The Liberator merged with Labor Herald and Soviet Russia Pictorial into Workers Monthly. An essential magazine of the US left.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1919/09/v2n09-w19-sep-1919-liberator.pdf