A terrific snapshot of the political economy, and hellish conditions, of the mining town of Tonopah, Nevada from a paper delivered by a wobbly to a meeting of the I.W.W.’s Metal Mine Workers Industrial Union No. 210 on October 26, 1924 and endorsed by that body.

‘A Perspective of Tonopah, Nevada’ by Card No. X-112357 from Industrial Pioneer. Vol. 2 No. 8. December, 1924.

Tonopah, Nev., October 28, 1924.

This article was read at the M.M.W.I.U. No. 210 regular business meeting, Sunday evening, October 26, 1924, at Tonopah, Nev. Motion made and carried that article be sent for publication to Industrial Pioneer (and other papers. — Ed.) Signed by Tonopah Branch, M.M.W.I.U. No. 210.

Data on Conditions in Camp and Mine

A SILVER mining camp is Tonopah. Here the “white metal” is mined, milled and refined into bullion bars, before being shipped by express to the Selby Smelter or perhaps the mint, at San Francisco.

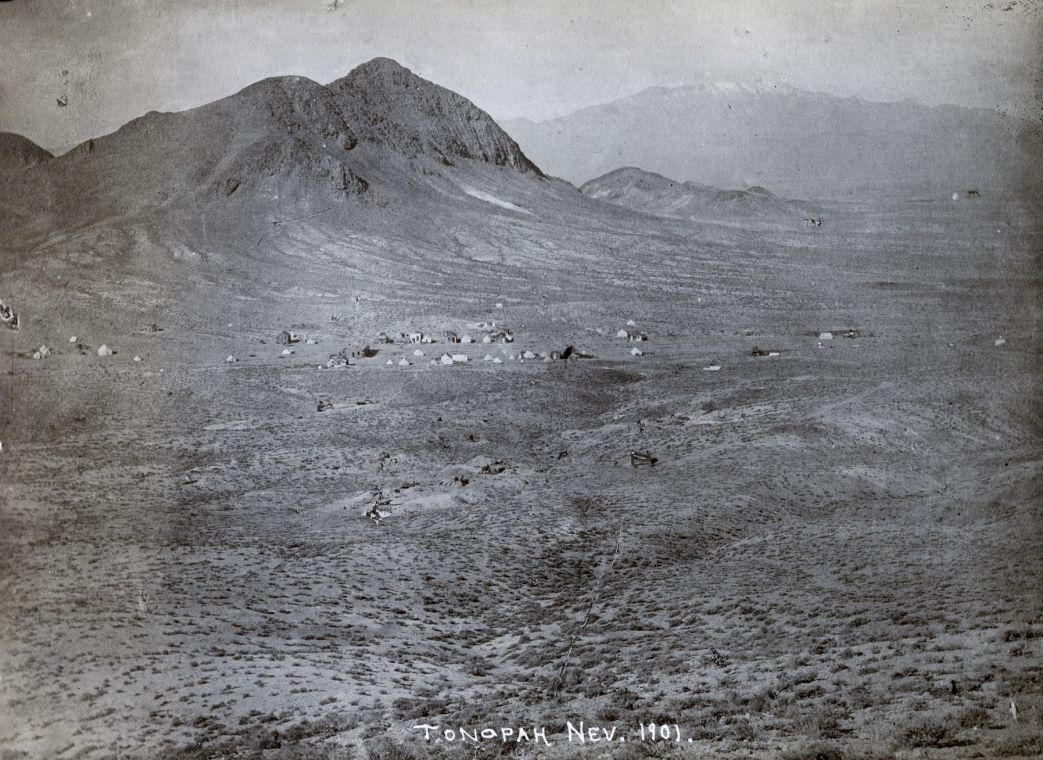

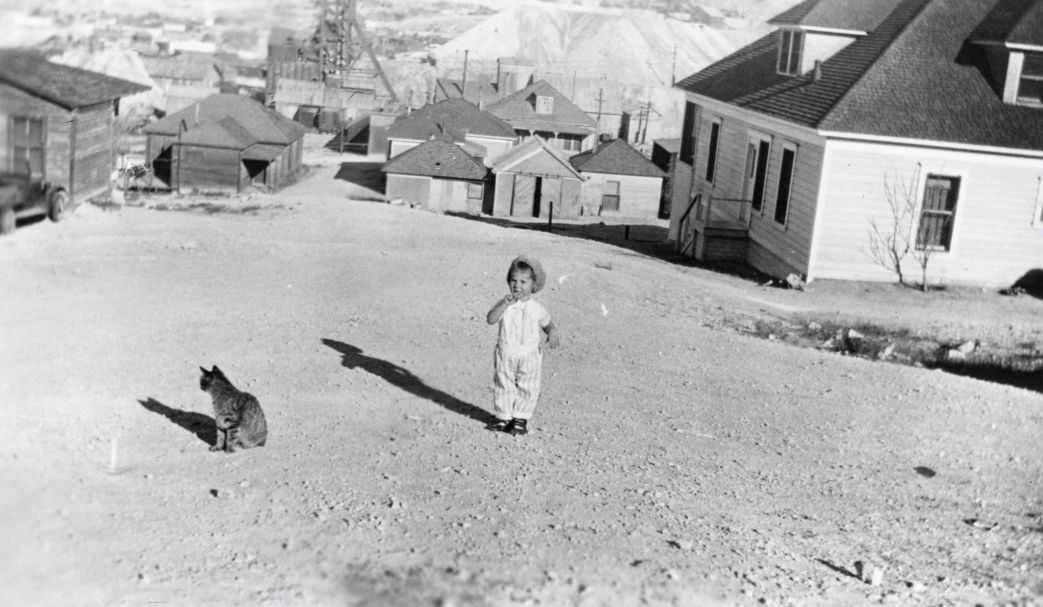

Tonopah is a typical desert town in southwestern Nevada — hot, dry and dusty in the summer time, windy and bitterly cold during winter months. Temperatures range from 100 degrees on hot days to 10 degrees below zero on cold ones. Altitude is 6,100 feet; annual rainfall about 6 inches; not a tree — not a stream; just a rocky, sagebrush, cacti basin on the west slope of the ridge, with stony hills and peaks surrounding the town.

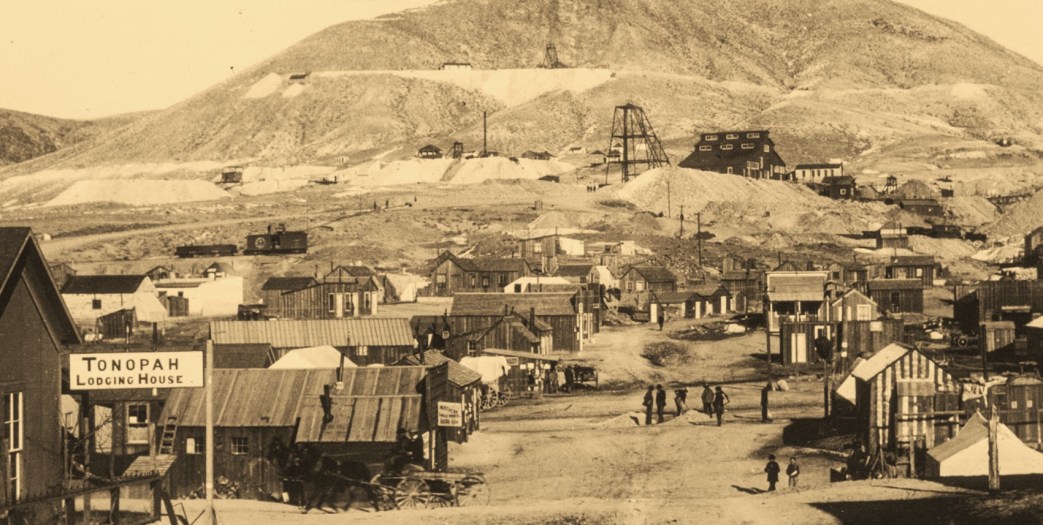

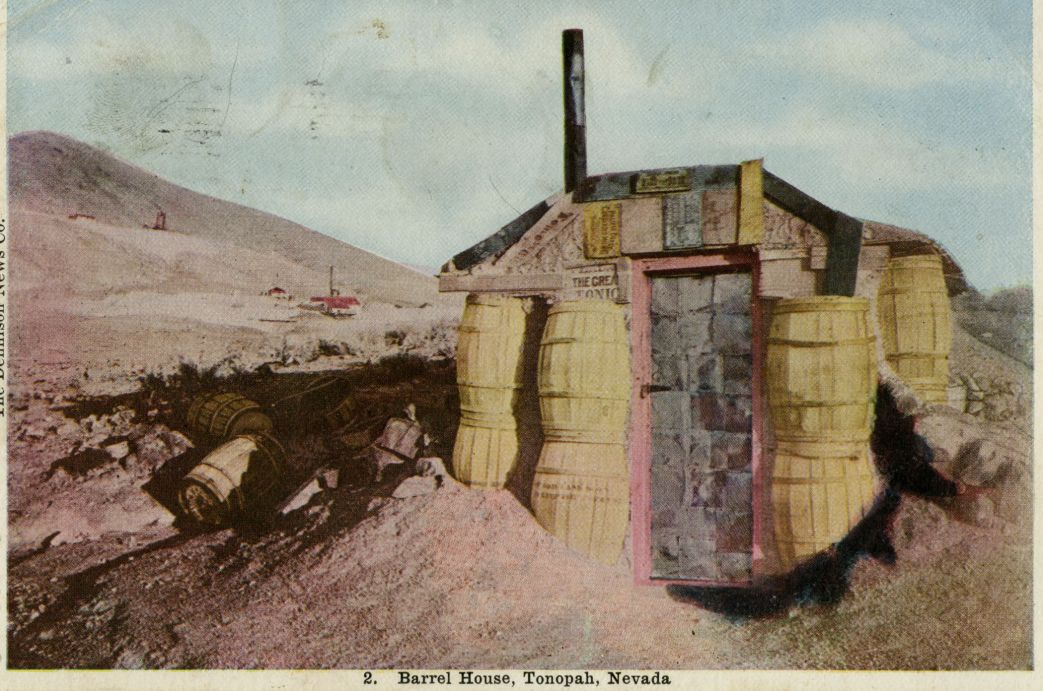

About 4,000 people inhabit this mining camp. Approximately 600 men work in the mines and mills. Other workers are employed by coal and lumber yards, garages, oil companies, in stores, etc. A few find work with the water, light, telephone and sewer companies. Tonopah has two daily papers with their staffs, politicians as usual; also school teachers and educators earn a livelihood by training the youngsters in the grammar and high schools. “Main street” for four blocks is one continuous row of “business houses.” Many of these are soft drink (?) places and clubs. There is a casino in the lower end of town whose furnishings and amusements are second to none in the west. The nightly “cabaret life” is a magnet in drawing the workers, to buy drinks and dance with the girls who work upon a “percentage basis.” The “Line,” where many men and women complete the picture, is in this vicinity and is common to nearly all mining camps. The accompanying photos will help the reader to a clearer perspective of Tonopah and its environs.

Born by Accident

This camp was founded in 1901 after a fortuitous discovery of a rich silver ledge outcropping on the hillside east of town. A burro’s slowness was instrumental in helping the prospector discover the white metal. The missile picked up to throw at the domesticated dumb slave was extra heavy, and proved to be a silver specimen from the ledge that erosion had loosened.

Tonopah’s early boom days were typical of frontier mining life — rag and tin houses — hardships and privations. Travel and transportation were by stage coaches and wagons. The first ore was hauled a distance of sixty miles to the railroad. High grade ore was necessary to pay the costs of primitive mining and transportation. Two of the old leather spring stage coaches repose in a yard at the foot of Main street. Some present-day residents rode into this arid pioneer town in these vehicles.

Two broad-gauge railroads now serve this desert section — one from the south, connecting with the main line of the Santa Fe at Ludow, Calif., the other from the north, leaving the Southern Pacific trunk line at Hazen, Nev. A dusty, stifling ride is encountered from Los Angeles to Tonopah via Ludow on a hot summer day, desert a-plenty, for 275 miles north of Ludow, past Shoshone, Death Valley and Beatty and on and on farther north.

Economic pressure must have been great to force men to brave this vast desert, suffer hardships and prospect in search of rare metals and minerals that, if found, might make them more secure in life.

It isn’t romance, nor is it the beauties of the desert that lure (?) men to these isolated spots. Some there are who sing and write about the wonders of desert greasewood and its aroma, of silvery moons and enchanted, starry, silent desert nights, but miners and prospectors usually have different perspectives from poets. Those who see romance and laurels in the mining industry have never drilled footage in the grinding, choking terror of the mine; they have never experienced a mine fire, a cave-in or a flood.

Economic Determinism

It is economic determinism that forces men and their families to take up abode in these “out of the way places” on a dry desert. The early pioneer was governed by the same urge. The struggle for existence makes species migrate in search of greener fields, more favorable spots where competition is not so keen and subsistence is assured. That is why the emigrants crossed the plain to California, to Nevada, to the Comstock, to Tonopah and elsewhere. The “Big Wide West” was the path of least resistance to escape the early factory exploitation system. (Eulogists of the Trail Blazers, take note!)

The concentration of mining wealth has gone on apace here in Tonopah the same as in other communities. The prospectors and miners of Butte, Montana, once owned “the richest hill in the world,” but now the Anaconda Copper Company claims it. They have dispossessed the pioneer owners. They dominate the state of Montana — exploit the great natural copper resources and the workers by the wage system of exploitation.

The mining companies of Tonopah have acres and acres of mining claims. The ore deposits are striking toward the west of the district and a rush has been made to locate and file on claims out on this big flat territory that was considered outside of the ore regions.

Hundreds of the populace have located and filed on claims. It is their “birthright” to have access to Mother Earth. But how does their “birthright” slip from them? “The History of Great American Fortunes,” by Gustav Myers (Kerr Pub. Co., Chicago) tells how the land and natural resources were stolen by fraud and graft, as instanced in the huge railroad land grants, timber steals, oil and mineral frauds, etc.

These recent claim filers cannot compete with the established silver mining companies. The populace on the average can’t sink modern mine shafts, but must sell their “birthrights” to the corporations for a few hundred dollars. These mining companies will then extract the mineral wealth by using the locators as their wage slaves.

Some system, isn’t it, in this great land of opportunity, where everybody is supposed to have a chance, where honest effort fills the cornucopia, the symbol of plenty?

Machine Ousts Prospector

The prospectors are vanishing. No longer can a windlass compete with a modern mine hoist. Private ownership of the means of life has been concentrated to such a degree that the few own all while the many have empty hands.

This is the machine age of production. Capitalism is on the stage now and is playing its final acts before the curtain drops on the social drama of “Dog Eat Dog.”

The present economic system is sick and needs constant bolstering to keep the structure from crashing to the ground; it has no equilibrium. The profit system is a contradiction; it robs and beats instead of assisting and providing.

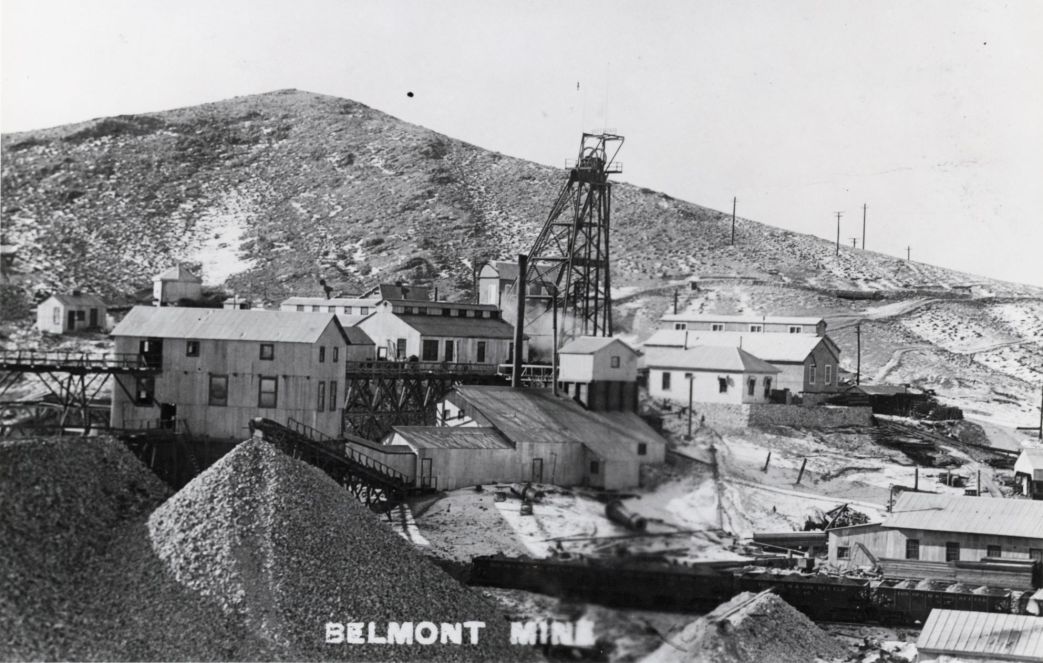

The total production record of Tonopah mines is high. Nearly 7,000,000 tons have been dug from its wonderful veins. A deposit now being mined in the Victor shaft of the Tonopah Extension Mining Company (which is the largest producer) has a width of 110 feet and 600 feet long, of a good grade of silver ore. Last month a record shipment of bullion was made — the stated value being $234,000 for one month’s production. The total production values of the district amount to the huge sum of $130,000,000.

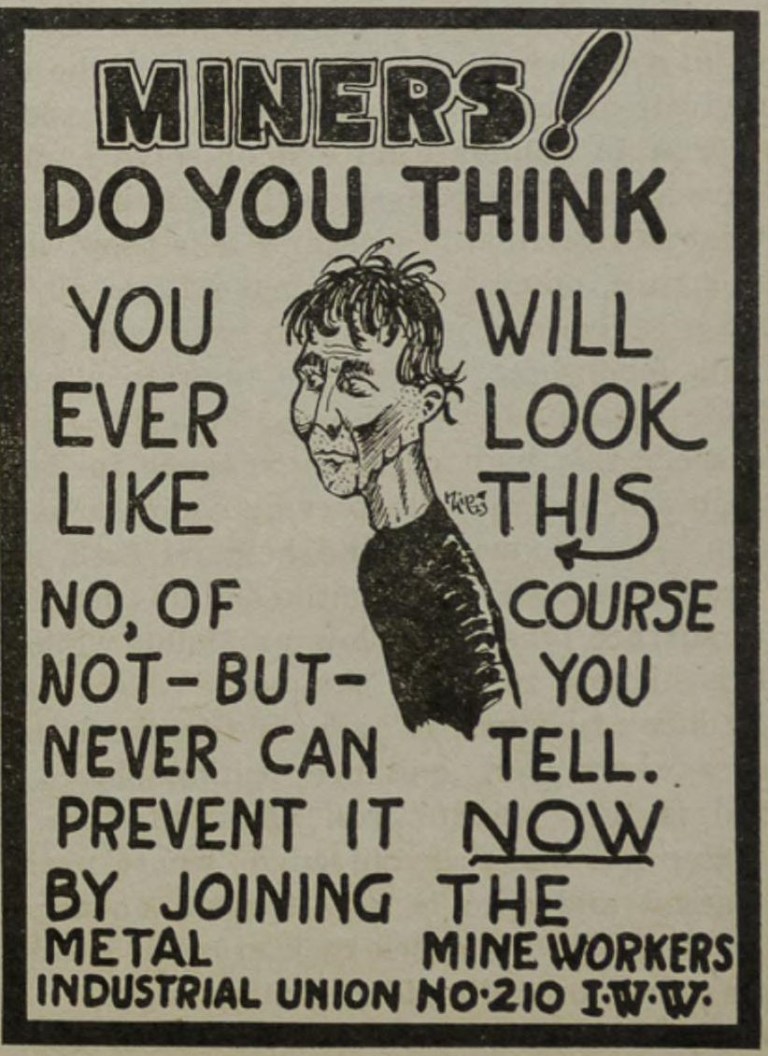

The Rotary Club of Tonopah has cast about for a suitable slogan to advertise this great silver mining camp and offers a cash prize for the best one submitted. A truthful slogan, one that would give facts, is no doubt sought for. I suggest this slogan: “Tonopah, the producer of white metal — and the white plague.”

One Dusty Hell

Miners of wide experience declare these mines to be the worst of all to work in, being hot and dusty, temperatures as high as 120 degrees, with humidity near the saturation point. In these “hot boxes” men work with just overalls and shoes on, and these get soaked with sweat in a few minutes. Until recently drilling with air machines (the stopers — “widow makers”) was done without using water to prevent dust. The cuttings from this rock are sharp and glass-like. They stick to the tissue of the workers’ lungs and cause a wasting away process known as the “miners’ consumption.”

In some cases it takes only a few months of this kind of work and these kinds of conditions to sap the miners’ vitality to such an extent that if they do not get out of these mines and find work that is not injurious to the lungs they are soon planted out in the “boneyard” — the local cemetery where hundreds of workers’ bodies are buried.

The water connections to drill machines and the use of hollow drill steel for water to reach the dust at the drill bit is not a total success; considerable mud and water is spattered over the machine miner and rheumatism is contracted. Again, the hole in the drill steel gets plugged up for various reasons, and the cuttings are dry and dusty.

The dust evil is far from being solved. The stopes and drifts are laden with dust and air currents keep it in motion. The mines are still claiming their toll of lives and the underground workers show visible effects of this dust scourge. Nor does it end with the miners; the population of Tonopah breathes the dust laden winds that carry back the dry mill tailings that are spread out over the flats below the town. Reports of government doctors state that a high percentage of the residents in Tonopah are afflicted with consumption. All this is a manifestation of civilization — of modem silver mining processes! Efficiency engineers direct these enterprises — well, anyway, lots of bullion is shipped!

Swiftly to the Grave

The speed-up is used here. One man on a Leymer machine is required to drill a certain footage or break so much “muck”, excuses for failing do not suffice — a time check is given the worker who would dare slow down. Where miners have better conditions and something to say in regard to work performed, two men on a machine is the rule instead of only one as in Tonopah’s mines.

The general working conditions in these great (?) silver mines and mills are at a low ebb. Men are underground for eight and a half hours; lunch is eaten in the stopes and drifts; ventilation and sanitation in the mines and on the surface need immediate attention, for these conditions cause industrial disease and a high, death rate.

The surface drys and locker rooms are stifling with foul odors from sweaty garments and modern flush toilets should replace the open filthy “out houses” around these shafts. Some mines have no change rooms — no shower baths — not a sign of a sanitary toilet.

Workers come out of these hot, foul mines and go to their rooms or homes, where a bathroom or other modern conveniences are rare. Tonopah is not a camp noted for sanitary conditions, and what there is comes high in cost; barber shop baths 50c — haircutting, 75c — shaves, 35c — the domestic water rate is three and a quarter cents per gallon. The water supply is pumped in from Rye Patch, a distance of fourteen miles north of Tonopah. A service charge of $2.50 per month for residences and more for business places is made by the sewer and drain¬ age company. Sewage is dumped below town a short distance, making a foul place at that point — no treatment plant here.

Coal is shipped in from Utah and is only $20.00 per ton — cord wood $18.00. Necessary articles are high priced-— desert food prices. Rents for modern houses are $30.00 per month — shacks, $10.00 to $20. 00. Bootlegging is rampant in this camp, as it is in all the states of the country. Federal prohis make an occasional raid — confiscate a “still” or two then booze prices soar.

Fighting Effects

The dry raiders are “chasing a will-o’-the-wisp” — are in a vain pursuit. It’s only fools who dabble with effects of things; common sense and experience prove that to eliminate an evil or solve a problem the cause or the root of the evil must be attacked. That job is left for the workers; it is they who will clean up the mining camps — make them fit places in which to live and work, where they will not have to drink moonshine in order to tolerate almost unbearable conditions.

To meet this high cost of existence in Tonopah the following wage scale prevails: miners and timbermen, $5.75; muckers and helpers, $5.25; hoisting engineers and blacksmiths, $6.00 per 8 hour shift; surface labor is as low as $5.00, while shaft work is highest at $6.75 per day.

The labor turnover is high, due to the hardships. Some workers stick and are willing slaves — their reward is the “miners’ con” and ultimate death. The camp has many an old miner whose usefulness has passed and who is now thrown on the scrap heap, just like a discarded rock crusher, a worn out sinker pump, or a dilapidated mine cage.

When will slow industrial disease be compensated for the same as swift industrial accidents? The latter is covered by the state compensation while the former receives no attention — yet workers’ vitality is ruined on the fields of industry.

Workers of Tonopah — you must fight your own battles. Nothing is ever given to you gratuitously — the conditions you now work under (as bad as they are) were fought for by the miners and other workers of yesterday — the recent strikes and demands of 1919-20-21 should be experiences of value to you — there is urgent need for further progress.

Join The I.W.W.

The next progressive step for the workers in the mining industry is toward establishing the 6 hour day. It is imperative, not only in one industry, but in all.

The advancing machine processes, the standardization and simplification trend, are carrying on production with fewer and fewer hands and at the same time increasing the output of commodities. The shorter work day is the only logical remedy for unemployment and depression, and it is likewise a remedy to alleviate the dust evil and speed up in these mines and mills.

Is future history to record them as servile workers — enslaved and degraded? Or, on the contrary, will they shine as guideposts for future progress?

This article is an honest, truthful perspective, a vista or view, with data on conditions in this desert camp.

Exaggeration has not entered in the least; indeed, the picture could be more plainly drawn by citing specific instances of which there are many, but limit of space forbids that.

The mining companies and their tools are arrayed against the workers’ progress. Manifestations of the class struggle are always apparent. The progressive worker — the educator — the agitator — is not wanted on the jobs. The bosses attempt to weed them out, but as long as working conditions are rotten and wage slavery exists, there will always be agitation and radicals!

May the time soon come when the workers will not permit their vanguard to be jailed and imprisoned or sent down the hill because of education and agitation, but will rally ’round every class-conscious rebel worker and proclaim that “An injury to one is an injury to all.”

For we have a glowing dream

Of how fair the world would seem

When each man can live his life secure and free:

When the earth is owned by labor

And there’s joy and plenty then

In the Commonwealth of Toil that is to be.

The Industrial Pioneer was published monthly by Industrial Workers of the World’s General Executive Board in Chicago from 1921 to 1926 taking over from One Big Union Monthly when its editor, John Sandgren, was replaced for his anti-Communism, alienating the non-Communist majority of IWW. The Industrial Pioneer declined after the 1924 split in the IWW, in part over centralization and adherence to the Red International of Labour Unions (RILU) and ceased in 1926.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/case_hd_8055_i4_r67_box_006/case_hd_8055_i4_r67_box_006.pdf