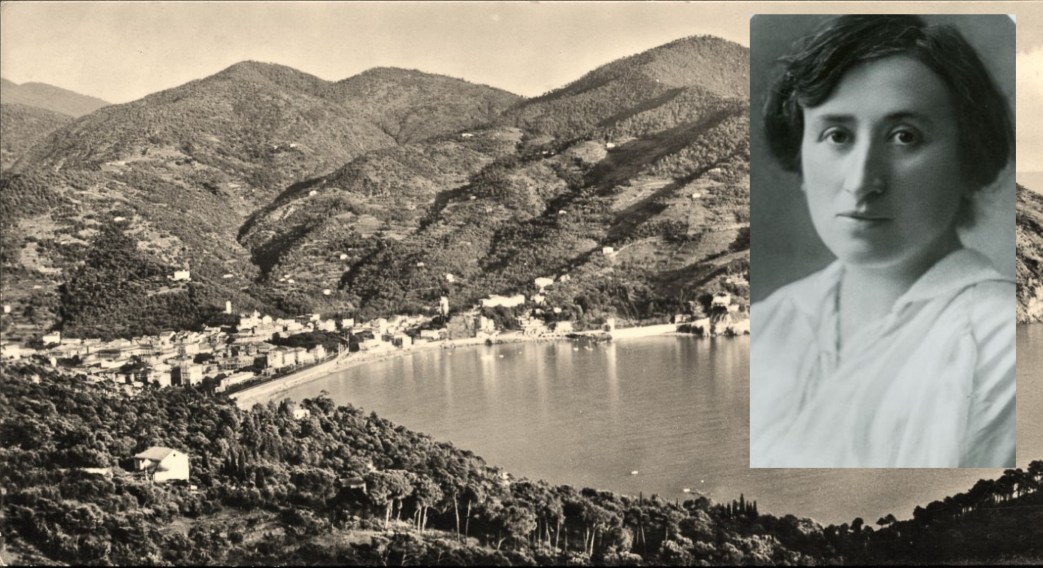

A wonderful letter from Rosa Luxemburg to Luise Kautsky written in June, 1909 from the Italian resort of Levanto and generously full of her allusions, observations, and insights.

‘Letter from Levanto’ (1909) by Rosa Luxemburg from Letters to Karl and Luise Kautsky from 1896 to 1918. Robert M. McBride and Company, New York. 1925.

Dearest Lulu:

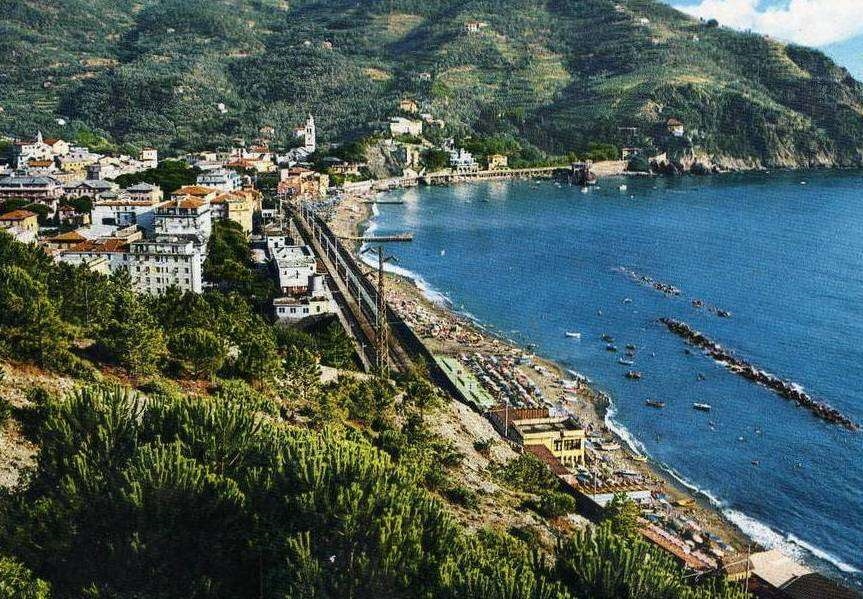

I received both your cards today — of the 9. and 11., together! Meanwhile you know that the package has arrived and are therefore reassured. I haven’t written for a long time because I had to slave away meanwhile and had one or two business letters to attend to daily besides. I therefore had no real leisure to write you as I wanted to. Also, waiting for the books made me impatient and “grumpy,” as Franz would say, and you know that I don’t like to show myself when I am out of sorts. Today there is sunshine again — within me and about me. As a matter of fact we had a whole week of rain, thunderstorms, cool winds and stormy sea. Today, suddenly, there is azure-blue sky, radiant sunshine and a deep blue ocean with whitecaps that glitter in the sun like snow. On the whole it is much cooler here than I thought and than one usually imagines. A friend writes me from Switzerland: it is beyond me how you can stand it now at the Riviera! I had to laugh, for to judge by the news received from acquaintances, it is much hotter in Switzerland now than it is here. Levanto is a tiny little nest, two hours away from Genoa, and as I did not know at the beginning whether I would stay here — conditions were totally strange to me — I did not give you the address right away, nor did I give it to the Friedenau post office, since Levanto is unknown in the wide world — (thank God!) — and the letters might possibly wander somewhere into the Orient. But I have remained here after all and am also receiving my mail, albeit with swinish tardiness.

Now as for your and my plans. I am almost certain to go to Switzerland in July, and I hope that it can be arranged for us to meet there. It is self-evident that I shall notify you at once as to where I am going, as soon as I know it myself. For the moment I can’t make up my mind, but I imagine it will finally turn out to be my beloved Lake Lucerne; only I fear, judging by long experience, that I shall roast there much more than here in Italy. Where do you intend to spend the three weeks in Switzerland with Karl? Write me about it immediately in case you have your eye upon something definite; that will probably help me make my plans. Also write me exactly when Karl will arrive in Genoa with Bendel — or are they going directly from Marseilles to Switzerland? Also, on what freight steamer they will travel (is it really a freighter? In that case the journey may be endless) Just wait till we all meet in Switzerland, won’t it be one joy and one talk-fest!!

My present nest is charmingly located on a little bay, fortunately without a harbor, so that no fishermen’s barges or sailboats profane the view as in Sestri Levante (where Gerhart Hauptmann sta lavorando nelle tranquillitd lucida et fragrante (“Is at work in the lucid and fragrant stillness”), as I have learned from the Secolo). Nor is it located along the tourists’ highway, like the Ponente and the Levante as far as Sestri, where the automobiles speed past and smell past. The little burg is surrounded by soft Apennine Hills which, covered with olive trees and sweet pines, afford a green of all shades.

It is very quiet here, only the tragic creaking of a mule’s voice is heard from time to time, as are also the insistent cries of the muleteers. As for the rest, a few sleepy figures stand before the entrances to a few stores on “Main Street,” and children play in the sand or white-red cats sneak across the street from one garden-fence to another. The center of the town, however, is a four-cornered Piazza Municipale around which is erected the Main Building with its galleries. In it you find everything that stands for authority, rank and state: the post office, the garrison (I suppose 6 soldiers with 2 officers), the podesta (the mayor), the customs office, and, of course, beside it a marble “memorial tablet” with two slightly projecting ledges on the side. Before this ‘“tablet” some passer-by or other is always standing with his back turned to the square, while otherwise the sun alone casts its rays upon the empty square. In the midst of the latter is the statue of Cavour, representing “the greatest dummy of the XIX century,” as the inscription wittily informs you (Al pin grande statisto) (“To the greatest statesman”). Otherwise one sees nothing except that the lavandaie (laundresses) are forever kneeling and washing by the narrow brook under three large cedar-trees, while the men would rather gossip than do anything else. Before my albergo (hotel), for instance, any two or three citizens will take posture or sit down on a protruding ledge and with the greatest of relish gossip for hours, while I boil inwardly, since this untiring babble of voices disturbs my trend of thought and I am tempted rather to throw down my work and sit down in the sun myself. In the evening, when it is cool, every living creature goes walking up and down “Main Street,” innumerable black children engage in games, and the “ice cream man” with his little cart does a land-office business. I, too, buy 10 centesimi’s worth of ice cream cone from him every evening, provided I succeed in wedging my way through the children that besiege him. Intellectually two persons stand out visibly above the rest: the post office official, a fat, round, swarthy, blooming young man, who during the hours after duty is the head and idol of the local jeunesse doree in his white shoes and Garibaldi hat set at a bold angle; in the evening, surrounded by friends, he tells jokes that I don’t understand and spreads good cheer and, as I fear, some free-thinking and cynicism about him. An entirely different sort is the apothecary, who, to be sure, is also in his best years, but who is pale and sullen and always has several equally serious men as well as the priest with him in his store. These sit with their hats on and discuss politics. They do this even when the druggist is away, for without him, too, they manage to entertain themselves well and to read the papers in his store. Twice already I have bought tooth powder from him, and every time he had to be called by one of the politics-talking gentlemen of the Clerical Party. Every Sunday there is a procession in which children, women and old men, garbed in black, participate; but the procession drags along lazily, the singing comes to a stop every few moments and the spectators laugh; “Signor Gesu” (Lord Jesus) who is dragged along on a long plank makes an unhappy face, as the radiant sun offends him and tickles his nose. This matter is not always as harmless, however, as it looks. Do you know where the storm and the rain came from last week? I read about it today in the Secolo: in Porto Maurizio on the Ponente a solemn procession had been arranged per scongiurare la siccitd. [To adjure the drought. — L.K.] And in the face of this one is not to believe in the divine Misericordia? Of course the drug store triumphed and with a cold smile looked in the direction of the post office party. At the same time giant placards of the Social Democracy concerning the 1st of May are in evidence at all corners. Nobody gets excited about it — possibly nobody got excited about it on May 1st, but I don’t know about that. Alas, the world is not perfect! Everything might be so splendid, only — only * * * First of all: the frogs. As soon as the sun sets, frog concerts such as I have never before heard in any country begin on all sides. Even in Genoa I experienced this surprise, for which I had looked least on the Riviera. Frogs — all right, as far as I am concerned. But such frogs, such a broad, snarling, selfsatisfied, stuck-up croaking, as though the frog were the first and absolutely most important person! * * * Secondly — the bells. I have high regard and love for church bells. But to hear them ringing every quarter of an hour, and an irresponsible, absurd, childish bimbimbim-bambambam at that — it is enough to make anybody crazy. Every Sunday and especially on Corpus Christi these thin bells wallowed for joy like pigs and couldn’t do enough of it. And thirdly— thirdly, Karl, when you go to Italy, don’t forget to take a box of insect powder with you. Otherwise it is wonderful here.

Carolus, a matter of business, in closing. Herewith the title of a new book by Lenin (his pseudonym is Iljin) [“Materialism and Empiriocriticism,” critical remarks concerning a reactionary philosophy. Moscow, 1909. — L.K.]; he is anxious to have the book noted among the works received. As far as a review of it is concerned, don’t ask it of anybody; I shall probably be able to recommend somebody to you, you might otherwise unwittingly give offense to the author. But enter the book immediately among the “books received” and also in the Literature of Socialism.

And now I kiss you, one and all, and you, Lulu, especially.

Your R.

Letters to Karl and Luise Kautsky from 1896 to 1918 by Rosa Luxemburg. Edited by Luise Kautsy, Translated by Louis Lochner. Robert M. McBride and Company, New York. 1925.

Contents: Introduction by Luise Kautsky, Beginnings, 1896-1899, Incipient Friendship1900-1904, From the Imprisonment at Zwickau to the First Russian Revolution, The First Russian Revolution 1905-06, Up to the World War 1907-1914, Letters from Prison During the War 1915-1918, Postscript by Luise Kautsky, Appendix: Biography of Karl Kautsky. 238 pages.

PDF of original book: https://archive.org/download/lettersofrosalux0000unse/lettersofrosalux0000unse.pdf