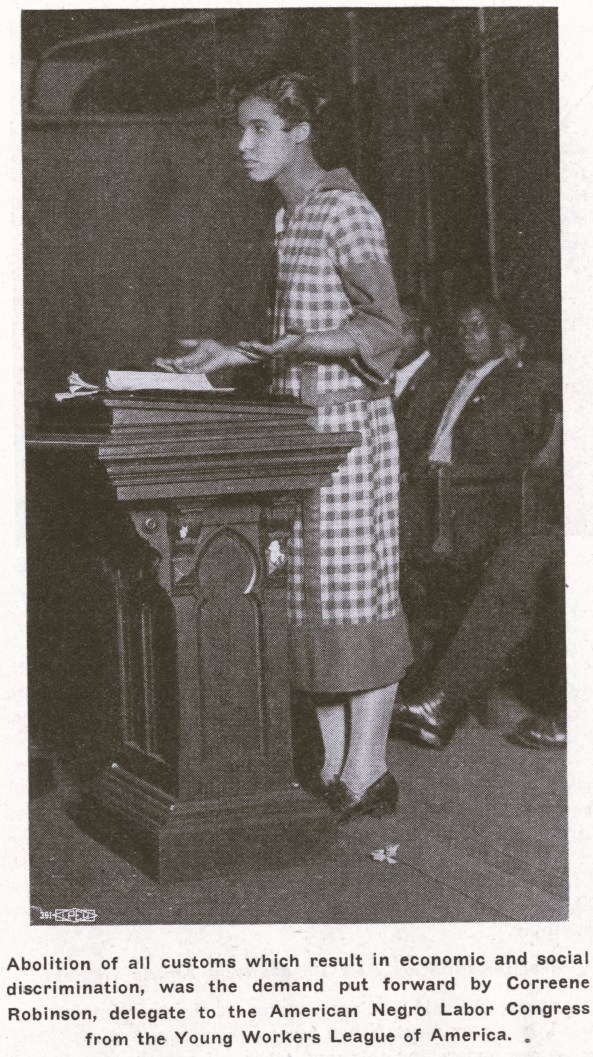

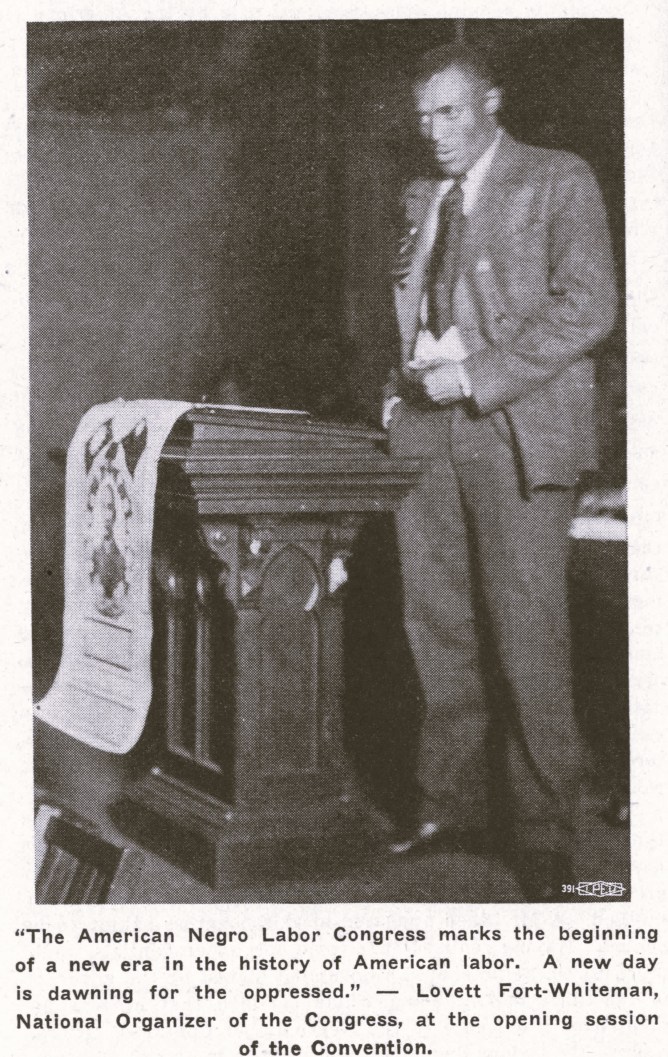

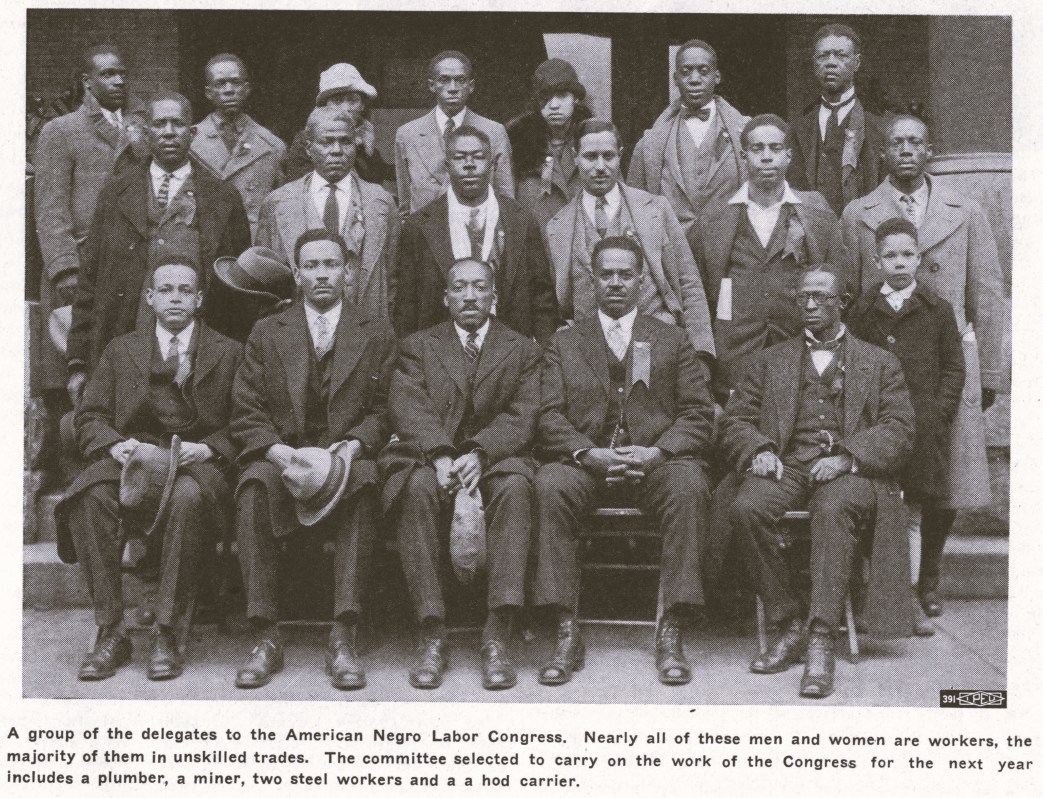

The Communist Party gained its original Black cadre, figures such as Cyril V. Briggs, Otto Huiswoud and Lovett Fort-Whiteman, largely through the merger of the African Blood Brotherhood with the Workers Party in 1922. However, it would be several years (and continued Comintern insistence) until the Party attempted to specifically organize Black workers. The first such organization was the American Negro Labor Congress founded in 1925. Here Robert Minor, a leading advocate of the orientation to Black workers, reports on its founding convention.

‘The First Negro Workers’ Congress’ by Robert Minor from Workers Monthly. Vol. 5 No. 2. December, 1925.

FOR the first time in the history of the United States (or practically for the first time), an American Negro labor convention has been held. Never before, with the exception of the years just after the Civil War, has there been even a pretense of a big national congress of Negroes on the basis of their class character as workers.

Negro conventions and Negro societies have been many and frequent, especially since the world war. But always these “conventions” have belied the real character of the Negro masses. There have been church conventions which reflected of course the blight of organized superstition taught to the Negro by the white master class. Or there have been conventions of Negro business men in which all of the realities of the Negro’s situation in American society were ignored in order to give a few Negro small merchants, lawyers and bankers a chance to pose in the attitude of “optimism” of the white Babbit-bourgeoisie. There have been conventions also of “classless” Negro associations, in which the same small merchant and professional class (representing no organizations but possessing the railroad fares) took the lead and also struck unreal poses; and conventions of Negro teachers suffering under the sorest grievances but fearfully avoiding all suggestions of the only remedies which exist. Then there have been the conventions of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People—an organization resembling in its pattern the ancient Abolition society and breathing the spirit of the white philanthropist in benign collaboration with colored bishops and lawyers, and, of course, the white Republican politician of the border states and other parts where Negroes vote and where anti-lynching speeches can be made.

Class Basis of Race Problem Previously Ignored.

All of these past conventions have belied the real position of the Negro masses in American society—have belied the class character of the Negro masses, have necessarily ignored the causes of the Negro’s oppression. In one instance a Negro convention made a gesture in the direction of recognizing the class character of the Negro’s problem; and strange to say, that was the convention (in 1924) of the most bourgeois of all of these organizations, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. It did make a demand on the American Federation of Labor for the organization of Negro labor in the trade unions—which may partly be accounted for by the strained relations between the white bourgeois politicians and the Negro petty-bourgeoisie at the time. There was one other instance in which a gesture was made in this direction—the case of the Universal Negro Improvement Association which in 1920 made a demand for the Negro’s rights in the trade unions, but which has since entirely forgotten the demand under the influence of a reactionary “Zionism.” With the exception of the African Blood Brotherhood, which had and still has a splendid “theoretical” program but which never attained mass influence, all movements among Negroes have ignored the class basis of the Negro’s problem, or have purposely evaded it, and as a consequence have been sterile or deliberately reactionary.

Subsidized “Negro” Press Attacks Labor Congress.

The American Negro Labor Congress which met in Chicago the last week of October, was immediately recognized as a breaker of traditions. It created more excitement in the so-called Negro press, I believe, than any other Negro convention that ever convened. Instinctively this congress was recognized as a fundamentally different thing, representing a rising danger to something or somebody, somehow. Among the most powerful of what pass for “Negro” newspapers, almost all confined their treatment of the affair, before its opening, entirely to veiled or open attacks. Anyone who knows that the lines of control of these most prosperous “Negro” newspapers lead through the Republican party, and through Washington and hence indirectly into the financial regions of Manhattan Island, will understand this. The American Negro Labor Congress represents objectively and ultimately a danger to those who profit by things as they are, because any movement which really takes the working class approach to the Negro masses’ problems has found the key by which those problems can be thrown open to solution. Hence the “master’s voice” spoke through most of the Negro newspapers (there were some notable exceptions), warning the Negro masses against the Congress or at least publishing as “news” Mr. William Green’s warning without publishing the answers of the Negro organizers of the congress.

But it is notable that not one of the most virulent enemy newspapers even attempted to deny the great importance and substantiality of the congress. Mr. Abbott’s “Chicago Defender,” the biggest of the Negro newspapers which push the white masters’ propaganda among Negro readers, took an attitude of complete but cowardly hostility toward the Negro workers’ congress, but did not even dare to deny that it had a great mass significance. Mr. Roscoe Conkling Simmons’ new paper, the “Chicago World,” which apparently lives on the lucrative trade of terrorizing Negro sleeping-car porters for the Pullman Company, published a vicious attack during the congress, but by the very prominence of the attack and the admissions in the article, acknowledged that the congress had wide importance as a mass phenomenon. And other papers more or less accordingly, although we must remember that some of the Negro newspapers were honest, sincere and fair.

What Mass Character?

But what mass character did the congress really have? The answer to this question is the important thing.

Anyone who regards the matter of the American Negro masses as one of deep, primary importance, and not as one of secondary importance—not as a thing to be judged by the scale of tempests in teapots—will not be ready to say that this movement is as yet a mass movement. The practically universal admission of antagonistic newspapers (both the white capitalist and Negro newspapers) that this congress was a large mass affair, must not be taken too seriously by the earnest young men and women who are at the head c! the movement. The fact that its enemies called it a mass movement shows what a low standard has been set for “mass” movements among such enemies. This makes a curiously interesting and profitable study.

A look behind the scenes of all Negro movements shows that they have practically all been nothing more than periodical conferences of “prominent persons,” delegated by nobody and present only by virtue of a vague general recognition and the possession of the price of a railroad ticket. This is painfully true, and it shows the fatal weakness which has spelled sterility for previous Negro “movements.” The essential fact was that behind such conferees there was no organizing of the masses. Bishops would be present because they were bishops, doctors because they were doctors, lawyers because they were lawyers, business men because, having succeeded in becoming business men, they were assume” to be the “natural spokesmen” for the Negro masses. No masses of hard-pressed Negro workers had gone through the organized process of selecting them. They were not delegates, which means that they were not a product of the process of organizing the masses. This was naturally so: doctors, lawyers, bishops and business men do not organize workers; and the Negro masses are workers.

That method of constituting Negro “conventions” the outgrowth of old traditions. And how easily it was assumed to be the only method was rather humorously proved at this Negro Labor Congress, which reversed the method. A Mr. Reed appeared at this congress asking to be seated. Having realized that some sort of credentials would be required, he presented a document signed by the governor of the state of Oklahoma which certified that he was appointed as a delegate to the Negro Labor Congress. It was a perfectly serious document, and strictly in accord with precedent. It meant that Mr. Reed was a prominent Negro citizen, and according to all tradition this was the sole requisite entitling him to voice in any Negro convention or congress. (He was seated as a fraternal delegate.)

Such traditions are clearly traceable to the Negro church, which for a full century was the only form of organization existing among Negroes. This trace is found also in the business proceedings of all previous Negro conventions, which have been mere “preachings” in which a leader, acting as chairman, ruled everything, decided everything, and hardly ever even thought of allowing a vote to be taken on anything.

Real Organization New Phenomenon Among Negroes.

It must be said that organization, in the true sense of the word, is a new phenomenon among the Negro masses. And when we understand this, and when we see the reversal of the traditions and forms of the past, we get closer to the answer as to whether there was a mass character to the American Negro Labor Congress.

A hard-boiled organizer will have to say that there were only a very few thousand of organized Negro workers behind the delegates who sat in the American Negro Labor Congress. There was only a small handful who directly represented trade unions, and to anyone who appreciates the essence of this as a Negro labor congress, the matter is highly important. Undoubtedly, however, the significance of this weakness is mitigated by the fact that many Negro “federal” labor unions which wanted to send delegates and which were watching with earnest sympathy its results, were finally terrorized out of sending their delegates by the threat of the president of the American Federation of Labor, who implied that these unions would be deprived of their charters if they participated. (A considerable number of unions were represented indirectly through the delegates of “local councils” in which they participated.) Another very serious weakness lay in the complete absence of representation of Negro farmers.

Must Build on New Foundation.

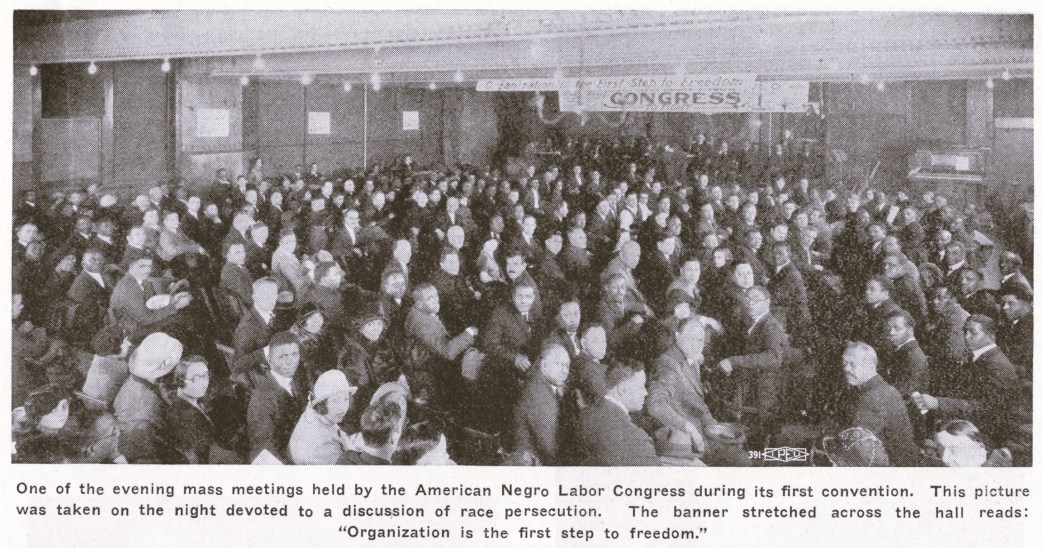

However, none but the blindest of fools could say that this Negro Labor Congress has no large significance. Whether the movement has or does not have a mass character is a question which was not conclusively answered by this convention, and which will be settled according to whether the young Negro leaders who have started it will now proceed to utilize the great beginnings which they have made. Unquestionably this convention resulted in forming a strong nucleus for a mass movement, and a nucleus which already has the begin rings of mass connections. The fact that it has succeeded in drawing together half a hundred young Negro leaders of exceptional ability—not “prominent persons,” but young working class men and women with the gift and urge for organization and a clear goal, and having behind them at least a frame-work of mass organization—this fact will be ignored only by skeptics who know nothing of present day history. The successful formulation of a clear program, and the reception of this program by the crowds of Negro workers who attended the congress, are also matters of much importance. This writer sat through the sessions of the congress from day to day, observing with keenest interest the development of the program, the uncompromising drive for what they wanted on the part of the delegates, the complete and enthusiastic unanimity of all delegates, ranging from Negro officers of A.F. of L. trade unions to the delegate “representing the State of Oklahoma,” and the reverberations of the program among the un-picked local Negro working-class audience which attended the mass meeting sessions by many hundreds. From these observations the writer can say with complete assurance that the program is not only one which gives the Negro movement the key to the problem, but that it is also one which spontaneously and completely captures the loyalty of the hitherto untouched Negro workers to whom it is offered.

Dicks and False Race Leaders Fight Congress.

In this respect a severe test had been put upon the convention by the attacks which had been directed against it. Universally it had been condemned as “red,” as Bolshevik.

The entrance to the hall was crowded every day with about a score of Mr. Coolidge’s federal dicks. Influential Negro politicians (under the direction of their white masters in the Republican party) worked overtime to terrorize the Negro population away from the affair, and newspapers with scare headlines virtually threatening the arrest of all who attended, were hawked at the door. Both the delegates and the big crowds of auditors were psychologized in advance to be suspicious and skeptical of any program that might be offered.

But the results proved that it is impossible to hold the masses of this oppressed people away from the measures which ring with sincerity and which go to the hard bottom of their problems. It was enlightening to hear the public reception given to the “first-comer” proposal in regard to the abolition of segregation of Negroes in the “black belt.” It is a proposal to take-out of the hands of landlords the right to refuse to rent apartments to Negroes or to fix the rental at a higher rate for Negro tenants; and this proposal of course means the taking over under public administration all apartment houses, an interference with the holy rights of property of the landlords. The fact that no one can conceive of any milder proposal for the abolition of the brutal segregation system, carried the proposal through with a whooping enthusiasm and complete unanimity (there being no “natural leaders” in the shape of Negro real-estate dealers present). The result of such a proposal is to present in a vivid way the realization that the liberation of the Negro masses from their condition of racial suppression (even the matter of residence segregation) involves a class struggle.

Green’s Attack Flat Failure.

The same lesson was learned through the handling of Mr. William Green’s attack upon the Negro Labor Congress as a Communist affair. This attack, and attacks of the same kind from a hundred sources, brought a reaction which slows that the average Negro worker today is far in advance of the white worker in immunity to the poison of Gompersism. Mr. Green’s platitudes are adjusted to the highly skilled craft unionist with a Ford and a cottage; and they roll off the back of the segregated, super-exploited Negro laborer like water off a duck’s back. A half-hour in the hall of the Negro Labor Congress would convince anyone that the American Negro cannot be told that he is “free.” Black men whose days are tortured with racial persecution in connection with a double degree of exploitation cannot be told to “let well enough alone.” For them the “well enough” is not in sight. Nor can they be told that “the ideals of the American Federation of Labor” are being threatened by the Communists without being made to wonder who those fine fellows, the Communists, might be. It is safe to say that Mr. Green’s attack made among the Negro workers a powerful propaganda in favor of Communism.

In fact, the many attacks of the enemies of the Negro people against the congress as a “Communist affair” simply brought about a condition in which hundreds of Negro workers in the audience, who had not previously any intimation of what Communism is, were wildly applauding every mention of Communism. It was not a “Communist affair’, but this had a tendency toward making it so. In connection with Green’s attack upon the Negro Labor Congress, it should be noted that the congress even before it opened had forced Mr. Green to make at least one gesture toward organizing Negro workers in New York. But in no case could the A.F. of L. bourgeoisie strike at the real problem by doing away with the Jim-Crow system: a few pitiful segregated unions “for Negroes” (like a southern railroad car) are about all that the A.F. of L. bureaucracy dreams of—for its purpose is not to give the Negro workers an instrument for liberation, but only to keep the Negro workers from building an instrument for freedom—to keep them away from the “social equality” movement and the Communists.

If there had been the slightest touch of sincerity about the maneuvers of the A.F. of L. bureaucracy, the resolution offered by a Negro delegate at the last convention of the A.F. of L. would not have been shelved as it was—that is, the Green bureaucracy did not dare either to turn it down openly or to pass it. It was a resolution calling for the organization of Negro workers in the same way that white workers are organized, in the same unions on equal basis. To this day nobody can say whether the motion was defeated or not. It has the distinction of having been acted on in such a way that it was neither voted down nor passed. Such a cowardly evasion shows the need of the Negro Labor Congress.

Toward Race Hegemony of Negro Workers.

A factor of primary significance in this congress is that it marks a big step toward the hegemony of the Negro working-class organizations in the general Negro race movement. Hitherto there has been professional-class leadership, as a matter of course, and with no organizational basis. Now for the first time, groups of Negro industrial workers begin to elect their delegates. That this tends to throw the center of gravity of the Negro movement into the Negro laborers’ ranks is obvious. And that many Negro middle-class intellectuals are bewildered and frightened by the fact, is but natural.

It was this rather than any “Communist domination,” that scared the Negro middle-class intellectuals. As a matter of fact there have been Communists in every important Negro convention that occurred in the last two or three years. In this Negro labor congress there was only one delegate representing the Workers Communist Party, whereas in most other Negro conventions there have been several. In the reactionary “Sanhedrin Conference” last year there were five delegates seated with credentials representing the Workers Communist Party. The difference in the case of this Negro labor congress is exactly in the fact that it was not dominated by any person or group—and the result was that it adopted all of the simple and plain demands that have been hidden in the minds of Negro masses for the past half-century but which have usually been choked in their throats by their “cautious” leaders of the middle class.

Local Councils Formed.

The organizational crux of the plan of the Negro Labor Congress lies in the formation of “local councils” in all centers of Negro population. The way in which the delegates seized upon this as the basis of successful organization, showed that there has at last appeared here a serious movement for organization. The idea is that such local councils will be composed of delegates from all Negro organizations, with special emphasis upon labor unions, in each locality, on the united front basis. Organizations composed of mixed black and white workers are included, and a peculiarly apt arrangement is for the inclusion of unorganized Negro workers in connection with the process of organizing them. The constitution adopted specifies that these local councils (like the national body) shall not become rival organizations as against other Negro organizations, or as against any labor unions, but simply a machinery for the creation and coordination of a united front. If this is adhered to, it will probably result in success where efforts to create a “newer and better” rival to other organizations would be a failure. From the speeches of the delegates one would judge that the establishment of these local councils will be the center of gravity of the work of the organizers.

Plan Inter-Racial Committees.

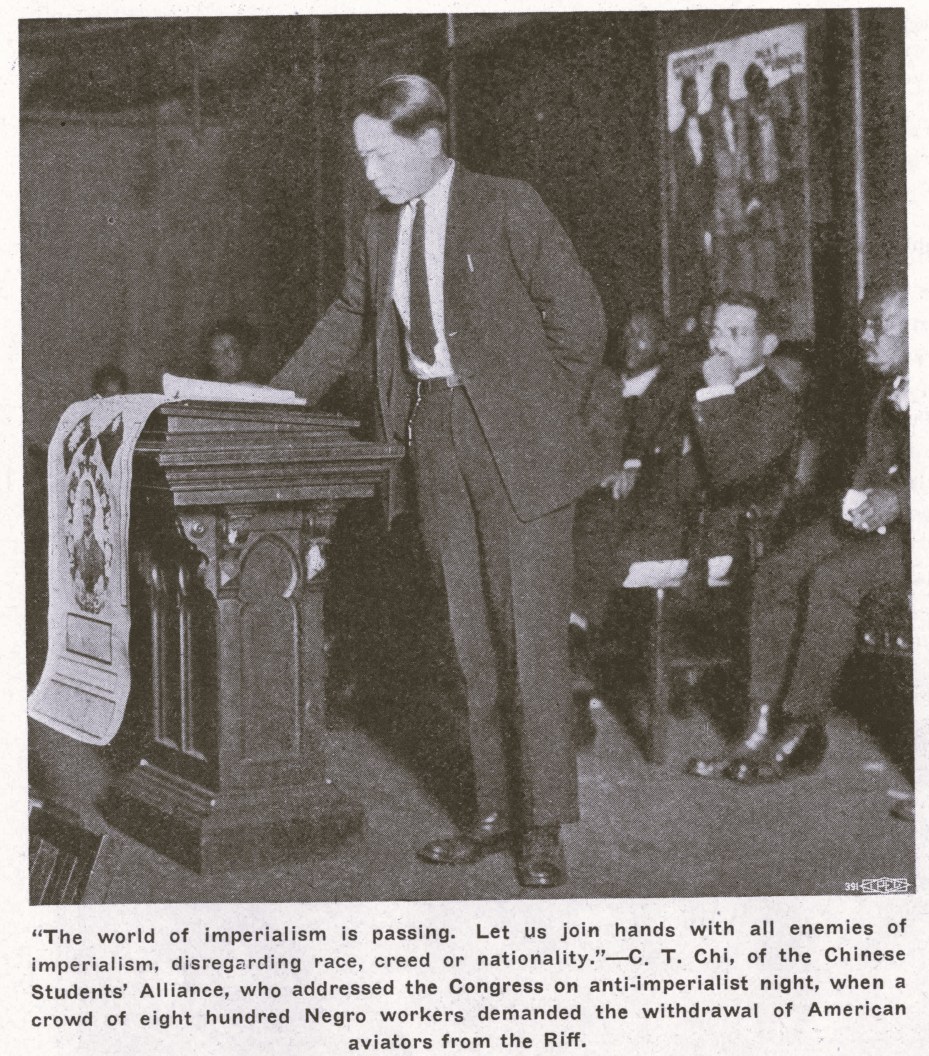

But the “united front” principle did not stop there. The congress made the refreshing declaration in ringing terms that the Negro workers demand that all of organized labor espouse their cause. This takes concrete form in the plan to form “inter-racial labor committees” in every locality, to be composed of delegates elected by the “white” trade unions and those elected by Negro organizations, to meet jointly for the purpose of bringing the Negro workers into the trade unions, preventing discrimination, under-cutting of wages, the use of one race against the other in strikes, etc., and for bringing about united action of all workers, black and white, against lynching and race riots. In this proposal there is a touch of reality that is nothing less than startling. If it is seriously taken up, it is full of potentialities for the future of the labor movement and of the Negro masses.

As the Negro Labor Congress had at least a sprinkling of representation from most of the big industrial centers, the character of the program, as one adapted to the mass needs of the Negro workers, and as one which is shown to be so adapted by the spontaneous acceptance of it by many hundreds who watched its development, can be considered in connection with the question of the mass character of the congress. I repeat that this question was not answered by this one convention, but is held in abeyance until the organizers show whether it is in them to utilize the nucleus and the connections which they have formed.

Lay Basis for Mass Organization.

This was the first American Negro workers’ convention. It had a reverberation of considerable magnitude among the Negro masses. It laid the basis for an unprecedented mass organization. It showed that there have developed among the Negro workers a number of strikingly able young leaders. For the first time it has thrown among the confused, misled and swindled Negro toilers a program adapted to the class character of the Negro masses. There is every reason to believe that upon the basis already laid there can be a congress of ten times the size and mass representation, within another year.

No one not a victim of gross ignorance of the subject, no one who is not a chronic skeptic in regard to the potentialities of the Negro, can deny that the American Negro Labor Congress was a success. All of those who participated declared that it was an inspiring, tremendous success; and its enemies admitted that it was so. But their estimate is not true yet—it will be true or untrue only after they shall have built upon the splendid foundation that they have laid.

The Workers Monthly began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Party publication. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and the Communist Party began publishing The Communist as its theoretical magazine. Editors included Earl Browder and Max Bedacht as the magazine continued the Liberator’s use of graphics and art.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/wm/1925/v5n02-dec-1925.pdf