Speech at the First international Congress of Negro Workers, Hamburg, July 1930 by secretary of the Gambia Labour Unions, and future leading Pan-Africanist, Edward Francis Small.

‘Situation of Workers and Peasants in Gambia, West Africa’ by E.F. Small from The International Negro Workers’ Review. Vol. 1 No. 1. January, 1931.

The general labour position in Gambia is a chapter of the old story oi imperialism. The final stage of imperialism has almost reached completion; the State machine is being continually turned from “benevolent and philanthropic” uses to serve exclusive capitalist interests; the Negro workers and peasants are the hopeless underdogs of the situation — the forsaken victims of capitalist and imperialist exploitation.

It is this fact that called the Gambia Labour Union into being one year ago. With the exception of administrative clerical workers, all workers and peasants are now represented by the Union. Of these an aggregate membership of 1,000 workers, and 2,500 peasants has been registered. Of course, they are all Negroes. As yet there is no European settlement. Europeans are employed in the administrative and mercantile departments as supervisors. They have no permanent interest in the land, 3 heir periodical tours to the Coast are prompted by motives of self¬ betterment, and racial aggrandisement. Therefore, all the same the race-issue in its broadest possible sense, is no less real in the relations of the white bosses to their black subordinates; this imperialist regime is naturally opposed to equal rights and opportunity, and conducive to race discriminations and disabilities of a colour-bar.

Within few months of its inception the Gambia Labour Union was called upon to face its first industrial struggle; for the first in time the Colony’s history, hundreds of operatives went on a general strike both for the right to organize in trade unions as well as for an increase of wages and better conditions of employment. I will emphasize only its salient features of the strike. Leading commercial firms in Gambia attempted to stifle the newly-formed organization at its very inception. They assailed the elementary right of the workers to organize in trade unions, giving the employees three days’ notice to quit the Union or be dismissed. Strike notices issued by the Union were treated with sheer contempt.

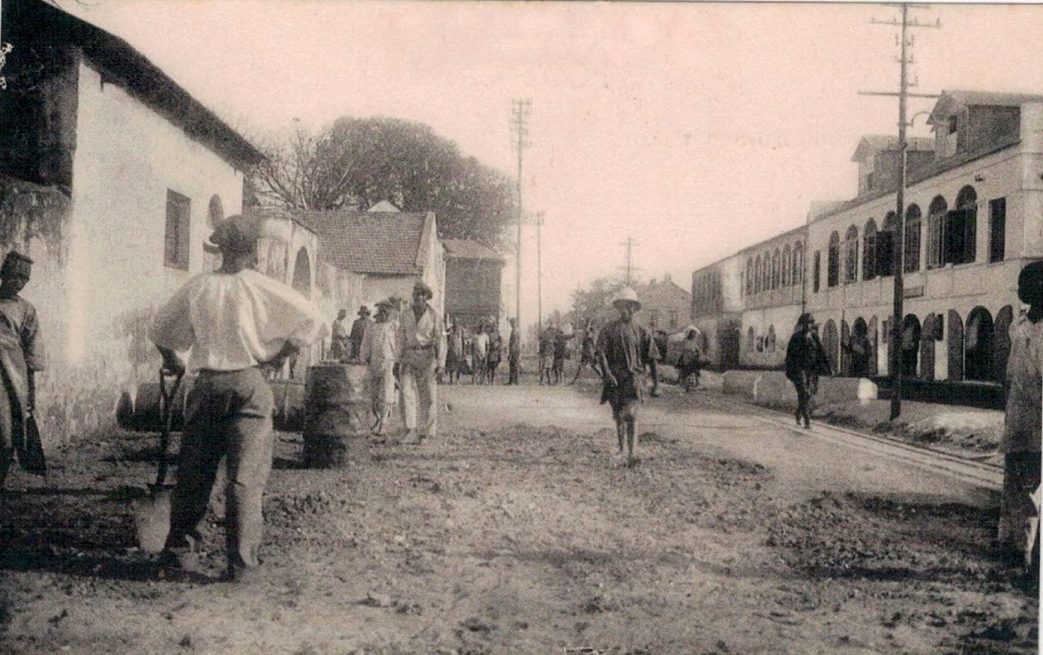

Before, during and after the strike the merchants had official support in their attempt to suppress the trade union rights of the workers. An official warning issued during the strike against alleged intimidation of workers had the practical effect of preventing picketing, and culminated in an armed Police raid on the 14th of November last, in which civilian passengers were wounded in the streets of Bathurst. So far standard minimum rates of wage have now been fixed jointly ty the Union and the Bathurst Chamber of Commerce, but in spite of the agreement reached in settlement of the strike, workers are being victimized by lock-outs, dismissals without notice etc. It is even proposed to import cheap labour from abroad, Jamaica and other places. And it is hoped this Conference will have some effect in preventing the victimisation of Negro workers by their own comrades.

A striking instance of the victimisation of trade union workers may be seen at the Public Works Department in Bathurst. This you will find combined with a system of piece-work and contract, which constantly throws the men out of work, and is a typical example of State exploitation of cheap labour in the guise of public economy. To carry out this anti-trade union system of exploiting cheap labour non-trade union foremen are employed, while there has been a lock-out of hundreds of trade union workers at the P.W.D., since last November. This lock-out had been threatened by the Government during the strike, when serious objections to the system were raised by the Union. Though the general works of the Department have been stopped for so long the estimated expenditure for the year is allowed to run as if there had been no close down, so that in the end the talk of public economy, is a mere lip-service.

Employment for the worker and peasant in Gambia is seasonal. That is to say it is limited to the period of the trade season, which is now regulated to last from December of one year to April of the next. This recent regulation, as will be seen in the case of the peasants, is a striking episode of imperialism. There are no manufacturing industries. The classes of workers are those whose services are required to carry on the trade in groundnuts, of which an average of 70,000 tons are exported annually from the Gambia. Comparatively few of these are regularly employed. The large majority are employed more or less for two to three months of the year. How can this majority subsist for the remaining nine months of the year? It becomes perfectly clear that these workers are faced by the most serious question of a living wage.

The workers and peasants in Gambia are in the most pitiable plight, there are no big farmers in the Colony, nor is there individual ownership of cultivable land; all such land is cultivated by a primitive custom of joint ownership. The peasant is employed during the lean months of wet season. During this part, there is a dearth of foodstuffs, and the conditions of life are the most miserable. The area on which food crops — rice, maize, etc., could be grown is severely restricted, and improved methods of cultivation are beyond the peasants’ means. To obtain money for his other requirements, therefore, they have to supplement the rising of a limited supply of foodstuffs by growing groundnuts so greedily hunted by the European capitalist.

The Government realises the extreme poverty of the peasant. But instead of relief advances are made to the peasants in the shape of a yearly supply of imported rice and seed-nuts. After harvest when he peasants try to hold out for better prices round goes the Government collector to demand the payment of the taxes and debts for rice and seed-nuts.

The poor peasants are thus forced to part with their produce at any price. They begin work each with a debt of £4 to £5. The peasant can reckon on an income of £7. Deducting from this the debt he has incurred of £4 to £5, he is left barely with about £3, on which to subsist with his family all the year round. Can you imagine the degradation to which he is reduced by such circumstances? Can you imagine how population could increase, or how the problems of disease and infantile mortality could be solved so long as the peasants hard toil is exploited to its utmost limit for the benefit of foreign capital?

It is important to note that in this state of affairs local merchants in Gambia have gradually diverted their attention from their primary interest — the profits realisable on the sale of capital goods, and are now concentrating upon making big profits from trade in raw material which they contrive to purchase at the lowest possible prices. In spite of the inevitable set-back this entails in goods trade, huge mergers, combines, trusts pools and participations, local and foreign are being formed to grind down the peasants and corner their produce. These pools are formed to exploit cheap labor and effect economies at the expense of the worker and peasant. Their natural consequences are large overstocks of goods and unemployment. The part the state machine is made to play in the crisis is the most remarkable. By the present regulation of the trade season you have seen how the interests of the peasants are played into the hands of the merchants.

While thousands of workers are being constantly thrown out of work there is no effort made to protect the worker or to relieve the unemployed; nor are the benefits of the Workmen’s Compensation Acts extended to workers in Gambia.

From the brief report you can see that Gambia is smarting from the effect of the economic and industrial condition that is sweeping the face of the world. The workers and peasants have experienced the needs for active resistance against capitalist and imperialist exploitation.

The workers of Gambia responded with great enthusiasm to the call of the International Conference of Negro Workers and Peasants. It is our hope that this Conference will go a long way to consolidate the forces of economic and industrial resistance against all forms of capitalist oppression not only among Negroes but among workers and peasants of the world.

First called The International Negro Workers’ Review and published in 1928, it was renamed The Negro Worker in 1931. Sponsored by the International Trade Union Committee of Negro Workers (ITUCNW), a part of the Red International of Labor Unions and of the Communist International, its first editor was American Communist James W. Ford and included writers from Africa, the Caribbean, North America, Europe, and South America. Later, Trinidadian George Padmore was editor until his expulsion from the Party in 1934. The Negro Worker ceased publication in 1938. The journal is an important record of Black and Pan-African thought and debate from the 1930s. American writers Claude McKay, Harry Haywood, Langston Hughes, and others contributed.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/negro-worker/files/1931-international-negro-worker-worker-review-v1n1-jan.pdf