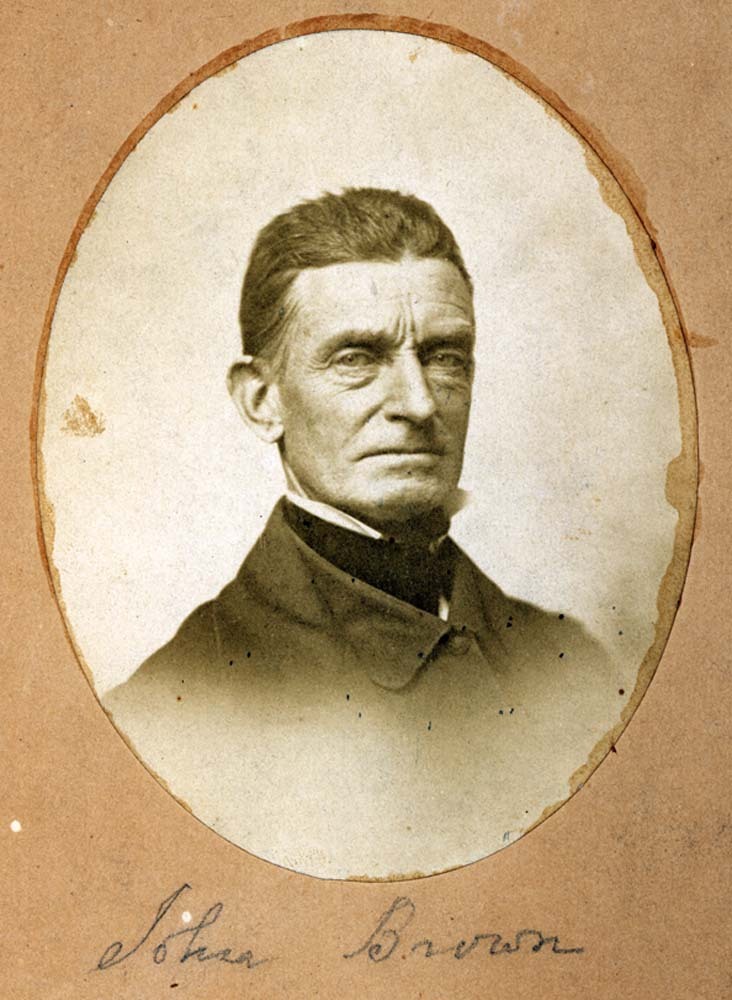

Nicholas Kopeloff compares the life of John Brown, dedicated to the abolition of chattel slavery, with the lives of the the Haymarket martyrs, dedicated to the abolition of wage slavery.

‘John Brown, Anarchist’ by Nicholas Kopeloff from Mother Earth. Vol. 1 No. 12. February, 1907.

This essay was read by Master N. Kopeloff, a young Anarchist, at the Ethical Cultural Society, to the great consternation of the teachers and pupils of that highly ethical institution of the ethical Mr. Adler.

When the Slave Bill was passed in 1850, compelling everyone to return fugitive slaves, one of its most bitter antagonists was John Brown of Osawatomie. Even in Boston, Mass., negroes were caught and sent back South to endure the torture of their cruel masters. But John Brown loved his fellow-men, whether colored or not; he longed to help the negroes escape their torture, and with that end in view he formed a faithful band of negroes in Springfield, Mass. (most of them refugees), to resist the attempts of the government to send back fugitives. This band of loyal and faithful negroes was called The Branch of the United States League of Gileadites; their motto was, “Union is Strength.” On the recommendation of John Brown they adopted a resolution, called “Words of Advice.” In this resolution we can trace Brown’s attitude towards the slave enactment. “Do not delay one moment after you are ready; you will lose all your resolution if you do. Let the first blow be a signal for all to engage; and when engaged, do not do your work by halves, but make clean work of your enemies.” And then come the noble and stirring words, “Stand by one another and by your friends, while a drop of blood remains; and be hanged, if you must, but tell no tales out of school. Make no confession. Union is strength.” Could anything characterize his forceful and determined nature better than this idea of doing a thing thoroughly, and then, if necessary, dying for it? Again, he says in a letter to his wife, “I, of course, keep encouraging my colored friends to ‘Trust in God and keep their powder dry.’”

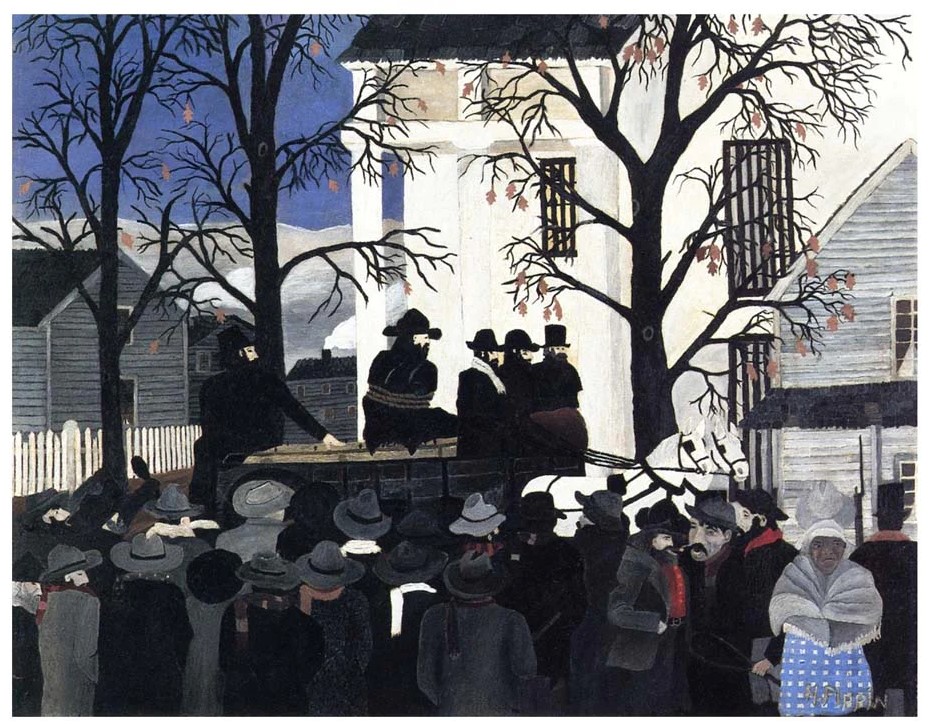

Brown was an Abolitionist of the highest type. Essentially a man of action, he was ready to do more than merely talk, should the time come for it, and it did come. It came at Harper’s Ferry, in 1859. With a handful of loyal and trusted men he attacked the garrison at Harper’s Ferry. But what chance had those few men of winning? With the flame of liberty in their eyes, and the spark of freedom in their hearts, they fought against terrible odds. What mattered it if a few lost their lives, when such an issue was at stake. They fought to the last drop, till, run through in a dozen places, Brown and his comrades dropped to the ground unconscious. He did not cease fighting when he had regained consciousness. He fought to the gallows for his cause.

When asked by a Virginian, when he was in prison, “Are you Captain Brown?” he answered, “I am sometimes called so.” “Are you Osawatomie Brown?” Lying there on his pallet pierced with bayonet wounds, he answered, “I tried to do my duty there.” That is the way Brown held to his duty.

But we have not sufficiently examined Brown’s actions; we have not followed his thoughts, his real objects.

John Brown was working in the interest of the slaves; his aim was to make them free. He wanted liberty— not only for himself, not only for the white race, but for all mankind. And he wanted liberty, even if he had to fight for it, and to defy the Constitution and break the laws of his country. In this sense John Brown was an Anarchist; that is to say, a man who prizes liberty above laws, above constitutions.

I trust that I am not misunderstood when I speak of John Brown as an Anarchist. I am aware that the popular mind is deluded with a false idea as to the real meaning of Anarchism. Some people imagine that Anarchists are people who roam about with knives in their hands, ready for indiscriminate attack. But in reality the Anarchist is a man who loves humanity and who, disbelieving in submission and invasion, hates only injustice and tyranny.

John Brown was such an Anarchist. Not that he did not love his country, but he loved liberty more, and at the call of liberty he was ready to break all laws, all constitutions, even to sacrifice his own life, like a true Anarchist.

John Brown, the Anarchist, belongs on the side of those other Anarchists who shared his fate—not at Harper’s Ferry, but at Chicago, in 1887.

The difference between John Brown and the Chicago Anarchists is but this: the former lived, worked and died for the liberation of the negro; the latter did the same for the modern white slave.

I find much similarity in the expression of last sentiments on the part of John Brown and the Chicago Anarchists.

On a memorable occasion, John Brown said:

“Had I so interfered in the manner which I admit— had I so interfered in behalf of the rich, the powerful, the intelligent, the so-called great—and suffered and sacrificed what I have in this interference, it would have been all right, and every man in this court would have deemed it an act worthy of reward rather than punishment.”

Albert Parsons:

“Had I chosen another path in life, I might be on an avenue of the city of Chicago to-day, surrounded by luxury; I would not stand here to-day on the scaffold; I would be pardoned if I were a millionaire.”

I quote John Brown again:

“Now, if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and Mingle my blood further with the blood of my children and with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, unjust enactments—I submit; so let it be done!”

Said August Spies:

“And if you think that you can crush out these ideas that are gaining ground more and more every day, if you think that you can crush them out by sending us to the gallows—if you would once more have people suffer the penalty of death because they have dared to tell the truth—I say, if death is the penalty for proclaiming the truth, then I will proudly and defiantly pay the costly price! Call your hangman! Truth crucified in Socrates, in Christ, in Giordano Bruto, in Huss, Galileo, still lives. They and others, whose number is legion, have preceded Us on this path. We are ready to follow!”

And now I quote from perhaps the most poetic of those noble men that suffered martyrdom:

“To-day, as the autumn sun kisses with balmy breeze the cheeks of every free man, I stand here never to bathe my head in its rays again…I trust the time will come when there will be a better understanding, more intelligence; above the mountains of iniquity, wrong and corruption, I hope the sun of righteousness and truth and justice will come to bathe in its balmy light an emancipated world.”

Could a more noble sentiment be expressed by anyone, Anarchist or not? How much more poetic, yet as real and firm as John Brown! And yet look how those men were hounded and slandered by the very people who revere Brown. They died in ignominy, as did Brown. But we have learned to respect and love him for his noble work. May the time soon come when we will learn to revere and love those noble men as we do John Brown of Osawatomie. Let us ignore whether a man believes as we do or not, but if he do a noble deed, let us praise him.

Mother Earth was an anarchist magazine begin in 1906 and first edited by Emma Goldman in New York City. Alexander Berkman, became editor in 1907 after his release from prison until 1915.The journal has a history in the Free Society publication which had moved from San Francisco to New York City. Goldman was again editor in 1915 as the magazine was opposed to US entry into World War One and was closed down as a violator of the Espionage Act in 1917 with Goldman and Berkman, who had begun editing The Blast, being deported in 1919.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/mother-earth/Mother%20Earth%20v01n12%20%281907-02%29%20%28-covers%20Harvard%20DSR%29.pdf