A look at the laundry industry and its workers for the I.W.W. magazine in the years just before the CIO made a breakthrough, organizing 100,000 workers into the Laundry Workers’ International Union the following decade.

‘Laundry Workers, They Can Be Organized’ by K. T. S. from One Big Union Monthly. Vol. 1 No. 8. August, 1937.

The worst sweat shops are found in the industries that require comparatively little capital to start. The man with a little money and a strong urge to get rich by robbing wage workers finds himself an old building facing a dirty street or alley where rent is cheap, buys second hand machinery, hires a few workers and goes into business. He works himself, if he can’t get out of it, cuts the prices on his product because he has to compete with numerous other budding capitalists who have the same urge he has, and tries his best to grind a little more work out of his employes than anybody else ever succeeded in doing.

The petty cock-roach is found in every city and town, and in the country, too. He is the mainstay of the capitalist system for he inspires hope in the minds of thousands of workers, who ought to know better, that there is a chance for them to escape from the chains of wage slavery and become independent.

One of the most popular of these stepping stones to wealth and affluence is the laundry industry. There are big corporations in the business, of course, but taken as a whole it carries on its miserable existence in that marginal territory where wages are lowest, working conditions the most miserable, and hours the longest.

The League of Women Shoppers informs us in an interesting little pamphlet entitled, “Consider the Laundry Workers,” that the modern power laundry got its start in California way back in 1849. It seems that the thousands of men who went out there without wives to wash their shirts and too much occupied with looking for nuggets to do their own washing, inspired a carpenter to build a 12-shirt washing machine which was run by a 10-horse power donkey engine.

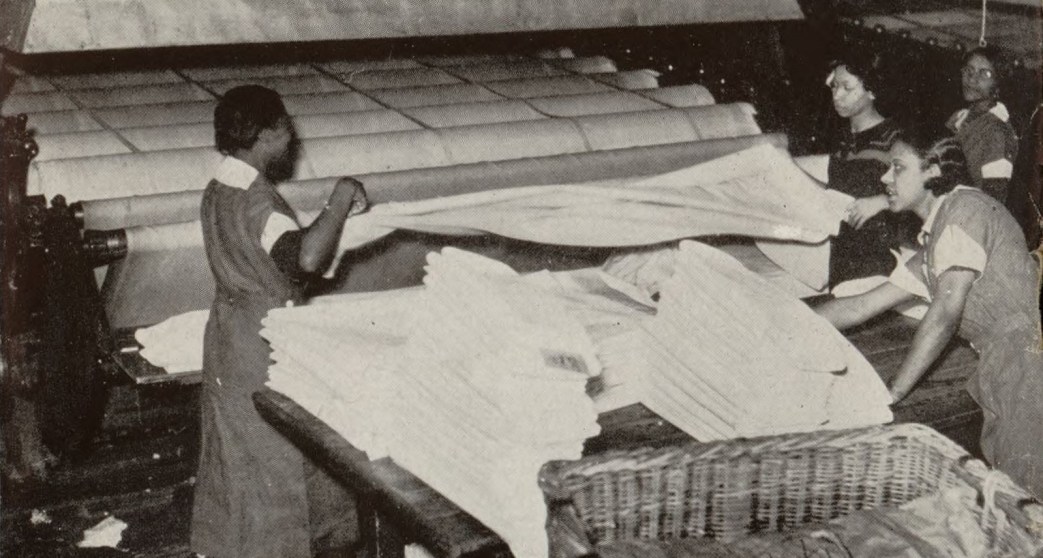

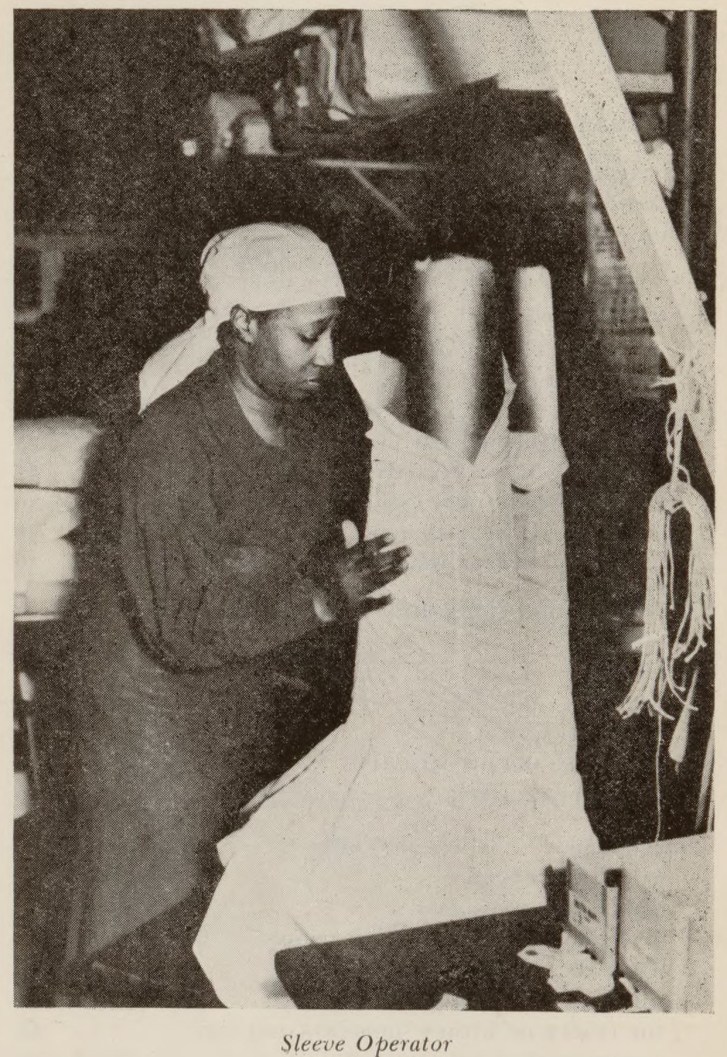

Since then the laundry machinery has become standardized and the operations and departmental divisions, too, so that the nature of the work done by the employes is about the same everywhere in the United States.

The business is highly competitive and, besides, it sells a service, not a commodity, and this service is one that people can dispense with in emergency. When depression strikes, women try to save money by doing their washing at home and this causes an immediate shrinking in the volume of work done by the laundries. But since employers will go to any extreme rather than sacrifice profits they make up by cutting wages down to levels almost unbelievably low, and keep them there as long as they can after the depression excuse is no longer valid.

Another factor that helps to keep wages down is the fact that by far the greater portion of the work is done by women who are not required to be skilled. The old tradition that women work for wages and outside of the home only to earn a “little something extra” is still used as an excuse for low wages and still influences the public attitude toward these workers; even though all the evidence shows that women as well as men workers go to their daily slavery, no matter how unendurable it may be, to ward off starvation and not to by diamonds.

New York State Labor Department figures show that in the latter part of 1936, 73.6 per cent of the women employed in New York City laundries made less than $15.00 a week. But investigators in the same area found wages as low as $6 for a week of 48 hours; and in Brooklyn a man laundry worker was found who was getting $5 a week for 50 hours work, and another who was paid $6 for 60 hours.

In the New York investigation the median wage for women was found to be $13 a week, and for men $14.50. The union wages were found to be somewhat above the average. For instance, while a union shirt folder made $1.95 for 100 shirts, the average was $1.50 for 100; and while a union washer (skilled work) was paid $40 for a 48-hour week, the average was only $22 for a week of 55 hours or longer.

No wonder the business flourishes. That it does flourish is shown by the report of the Consolidated Laundry Corporation (New York). In 1936 this corporation showed a net profit increase of $246,000 over the previous year. But wages went down, not up, during this period of business improvement.

While there was an average increase of 6.2 percent in women’s wages over 1935, the wages of the laundry workers dropped about 2 percent and at the same time there was an average addition of 18 minutes a day to their working time.

It is interesting to note that three directors of this corporation, who were also officers, received salaries amounting to $71,000 in 1935. Eight other directors, who were officers, received a total of $125,000.

Here as in other industries the lowest wages are paid in the smaller plants, those owned by that much lauded American who is bent on giving a practical demonstration that there is room on top for the ambitious go-getter.

New York had a minimum wage law which set the minimum wages for laundry workers at $12.40 for a 40-hour week, or 31 cents an hour. The old law has been repealed and a new one passed under which a board is to determine minimum wages on the basis of what a worker needs to exist on. Naturally the worker in the industry who does not use unfounded hope to excuse his own inaction in the fight for improvement, will not expect any more from the new law than he got from the old.

In the period in which the laundry slaves’ wages were falling, the cost of living was going up. Retail food prices rose 2 percent from December to January, rent rose 11 percent, and clothing rose even more than these. It is no wonder that the laundry worker often has to apply for charity even while he or she has a full-time job.

Wages vary widely in this industry. A man who worked 10 years in one laundry received $10 a week while another doing the same kind of work in another laundry received $17 after only three years experience.

The hours are invariably much too long, but for some they are positively inhuman. The men get the worst of it in this respect; 60 to 70 hours a week are not unusual. But the more humane hours for women are nothing to brag about, they often are as high as 50 and the average is 43. (The N. Y. State Labor Dept, found the hours for women to be 42.1.)

It is not necessary to state here what the living conditions of these workers are like. Every worker knows how hard it is to get along on what is called a good wage and can figure out for himself what a strain it must be to try to exist on what the laundry slave gets.

As to working conditions, the surroundings the slave has to put up with during the long hours he is on the job, these must be experienced to be fully appreciated. In this respect all laundries are bad, but some are worse and beyond description. The fetid odor that comes from laundry windows and doors and momentarily strikes the passerby like exhalations from some mysterious inferno doesn’t even suggest the conditions that exist inside.

Here is what some of these workers have to say about their work:

“The ventilation is awful. There’s not even a fan in the room. The walls and ceilings sweat terribly. It actually rains down on us. I really was healthy when I started but the damp and heat break you down. In two years you’re in pretty bad shape. I get colds all the time.’’

And another:

“Nobody’s health is good in a laundry. I had a breakdown from the work. Inhaling the steam keeps your throat dry and standing all day keeps your feet swollen. Some women get so weak they lose their grip in the hands and their arms.”

And another adds:

“What hope have the young, if this is their future? I have worked here for 15 years. I was making more six years ago than now. Gradually we were cut to $11 a week. I got laid off Saturday. They gave me my pay and said, ‘We don’t want you anymore. We have to have younger help!’”

The laundry bosses know and practice all the tricks common to employers who have their workers down where they want them. Many of them practice the ‘docking’ system just as old John Farmer does on his threshing crew (when he can get away wit it). If there happens to be no work for ten or fifteen minutes, that time is deducted. If there is extra work, requiring overtime, it is often not paid for at all.

When there is re-washing to be done, it is usually not paid for, and the girls are expected to do the bosses’ laundry after quitting time without pay. In some places the boss forces the girls to bring in their own wash and charges them the regular rate. A girl reports on one place where “they rung the bell for lunch at 5 minutes after 12, and then rung it again at 5 minutes to 1, chiseling us out ten minutes. And if I come in a minute late, I am docked a whole hour, but if they make me work an hour overtime, I don’t get paid for it. We work so fast that we haven’t got time to count the pieces, so sometimes the boss slips things in on us.”

These stunts will sound familiar to the workers in many other industries.

The only way in which the laundry workers can establish better conditions for themselves is to organize. Legislation is absolutely no good. It is a sign of the most slavish weakness for these workers to look for improvement from laws that the well-fed legislators see fit to pass and which the inspectors disregard if they provide for anything more than the bosses are willing to give. What the workers must do is to take the laundry bosses to a thorough cleaning with the help of a good union.

There are plenty of things that help make organization difficult in this industry. In many places the bosses play one race against another and in this way keep down any tendency on the part of the workers to get together. Foreigners and natives, Negroes and whites, old hands and new ones are skillfully pitted against each other by bosses who know that bigger profits depend on their keeping the workers suspicious of one another and disorganized.

Besides this and other considerations, it is always most difficult to organize workers in an industry where the wages are extremely low and the hours long. Low paid workers always are more in fear of losing a job than those that are better paid; and the long hours of hard work lessens the tendency toward and the desire for social contact with fellow workers after working hours. When their day’s slavery is done, they want to rest.

Nevertheless it is possible to organize laundry workers. Recent months have witnessed many strikes in the industry, most of them spontaneous and unorganized. There is a splendid field here for the I.W.W. member to do something for his cause if he is familiar with the industry and has contacts with workers in it.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/case_hd_8055_i4_r67_box_008/case_hd_8055_i4_r67_box_008.pdf