The mill town of Paterson, New Jersey saw some of the most class-conscious and militant strikes of the early 20th century. Here, Rebecca Grecht looks back at the that history and the conditions then facing the workers in the run-up to 1926’s epic confrontation.

‘Paterson-Field of Battle’ by Rebecca Grecht from Workers Monthly. Vol. 4 No. 1. November, 1924.

PATERSON, a historic battleground in the class war of America, is today the scene of another bitter labor struggle. For two months the broadsilk weavers of the “silk capitol” of the United States have been on strike in a fight for decent living conditions. And again, as in previous strikes, they have found opposing them not only the silk manufacturers but the force of the police and the courts. Mass arrests of pickets, injunctions, violent attacks in the mill-owned press, are today giving the Paterson silk toilers another lesson in the meaning of the class struggle and the capitalist dictatorship.

The strike, which began on August 12, was called by the Associated Silk Workers union of Paterson. It came as the inevitable result of the attempt to rob the silk workers of gains achieved through long sacrifice. During the past year conditions in the silk industry have been growing steadily worse. Not only has there been a rapid extension of the vicious three and four-loom system, but, close upon its heels-in fact, as an inevitable accompaniment-a decrease in wages of fifteen to twenty per cent, and an increase in hours from eight to nine, ten, and even eleven hours a day. How unbearable the situation had become can readily be seen from the fact that with little difficulty the union succeeded in bringing down almost all the silk weavers of Paterson. And these strikers have stood their ground loyally and militantly despite all efforts of bosses, police, courts, and press to intimidate and terrorize them.

Textile Mills Are Slave Pens.

To understand the significance of the present strike, it is necessary to know the general conditions of the textile industry. The struggle in Paterson cannot be considered as an isolated struggle. With strike clouds looming over the entire New England area, Paterson may well be the scene of the first battle in a far-reaching industrial conflict.

Conditions in the textile industry, which employs about one million wage earners, are among the worst existing in any American industry. The average annual wage of the textile worker in 1921, as indicated in the last report of the United States Census Bureau, was $902, or about $17 weekly-lower than the aver age for more than fifteen leading industries. For this wage, which is the prevailing one today, more than fifty per cent of the mill operatives slave nine, ten and eleven hours daily. Efforts to resist this exploitation have led to long and bitter struggles. The textile barons, who have netted millions in profits, have fought violently all attempts of workers to better their conditions. Today the textile industry is witnessing one of the worst slumps in its history. Of New England’s 315,000 textile workers normally employed. 200,000 are now idle. With this huge reserve army off the jobless at hand, the way has been paved for a general drive against labor.

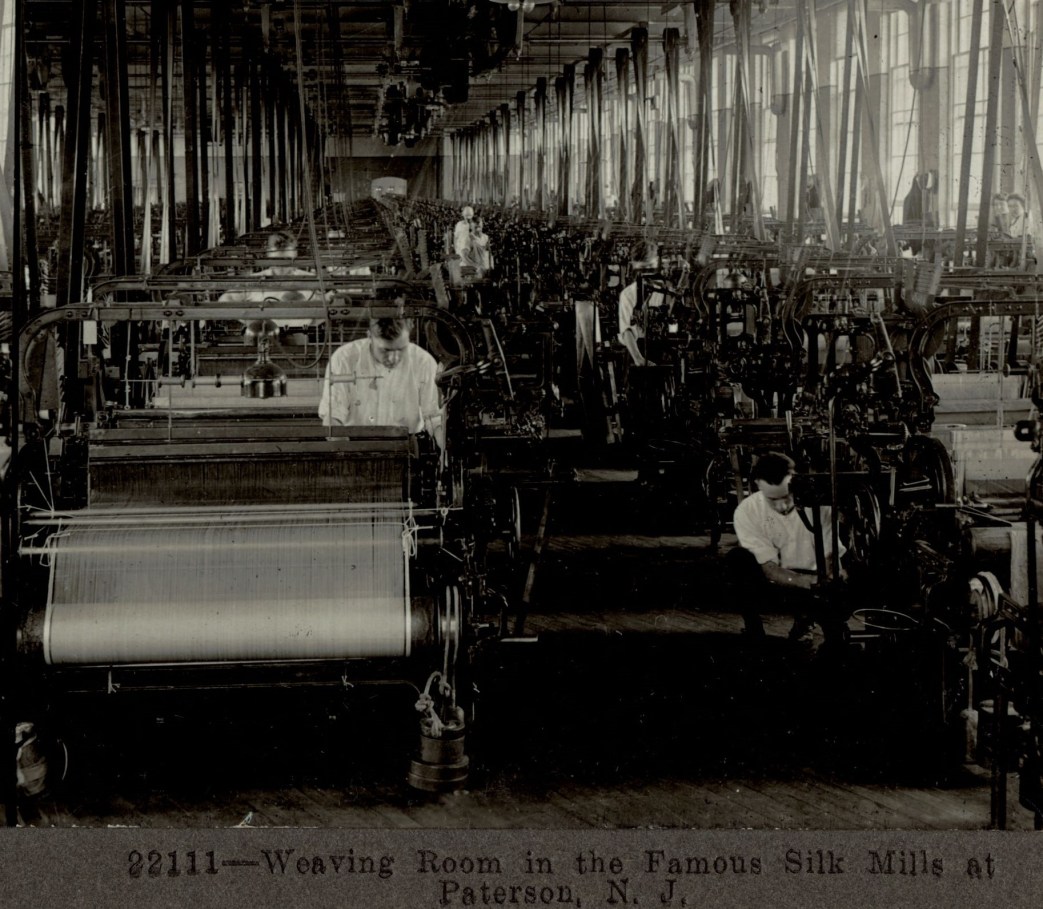

In the silk manufacturing branch of the textile industry, employing over 120,000 workers, conditions reflect this general situation. That silk production is highly profitable can be seen from the fact that within a comparatively short period the United States has become the foremost silk manufacturing country in the world, the raw silk consumed by American mills during the three years preceding the war amounting to almost as much as that consumed in France, Germany, Switzerland, and Italy combined. On the other hand, wages in the silk industry, though slightly higher than in cotton and knit goods manufacturing. have always been at a very low level. The mill owners prosper and silk production thrives at the expense of thousands of workers forced to toil in silk mills from nine to twelve hours a day under conditions which lead to ill health and disease. It is estimated that 19.8 per cent of all deaths among men, and 37.7 of deaths among women employed in silk manufacturing are caused by tuberculosis. That is the produce of a “flourishing” American industry.

Fragments of Labor Unions.

Despite the militant labor struggles carried on within recent years, the extreme exploitation prevalent in the textile industry has not been checked. The reason for this can be found mainly in the lack of organization among the workers. Less than 100,000 of the million workers employed are organized in trade unions. This in itself constitutes a grave weakness, as the unorganized masses constantly menace the fight for better conditions. And the situation is aggravated by the fact that these eight or ten per cent organized workers are themselves split into various unions. The United Textile Workers, the so-called bona fide union, affiliated with the American Federation of Labor, is the largest, claiming a membership of 50,000. Then there are the Amalgamated Textile Workers and perhaps a dozen other independent unions all opposing one another. No unity exists. As a result, even those workers who are organized cannot offer effective resistance to the oppression of the textile magnates, who thrive upon the absence of organization and solidarity within the industry.

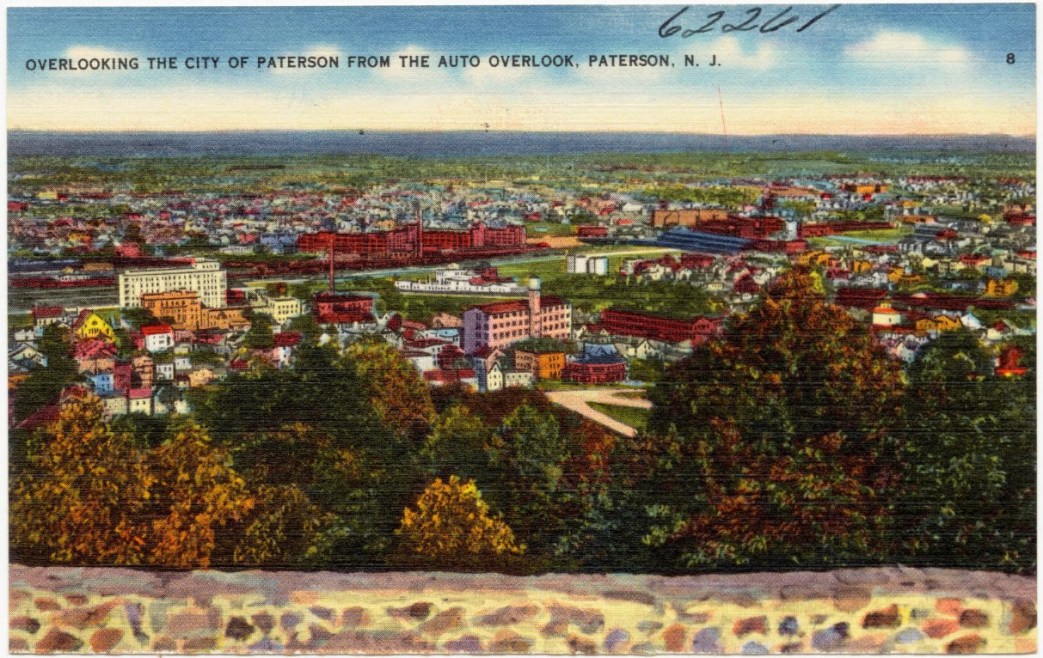

Until a few years ago, conditions in Paterson were the same. This city, the home of the first attempt to weave silk in the country, has fast become the silk center of America. In 1919 it had 574 silk establishments, about forty-two percent of the total number in the United States, and employed 21,836 wage earners. Since then the number of mills and looms has rapidly increased.

Because of its important position, Paterson saw the first serious attempts to organize the silk workers. There was no concerted drive for organization, but as the various trade unions arose in the textile industry, each tried to establish its own local. Under the leadership now of one union, now of another, the silk workers of Paterson have made repeated efforts to better their lot. In this they have from the very beginning met with the most bitter opposition of the silk manufacturers, together with the various agencies of government in Paterson.

The “First Revolution” of 1913.

While strikes had taken place before, there happened in 1913, what might well be called the first revolution in the Paterson silk industry. In that year occurred the general stoppage in which over 20,000 silk workers participated. The strike was called by the Industrial Workers of the World, mainly against the introduction of the three- and four-loom system. It was a long, intense battle lasting more than six months, and accompanied by acts of brutality and terrorism on the part of the police and courts which established Paterson as an outstanding center of industrial warfare in this country.

As a result of this strike, though no agreements were made with the union because the Industrial Workers of the World refused separate settlements, better conditions were gained in many individual mills, and a temporary halt was called to the spread of the multiple loom system. Far more important, however, was the brilliant manifestation of working-class power and solidarity which has made that strike a landmark in the history of the struggle of the silk workers against exploitation.

Following that, a degree of improvement in working conditions was gradually obtained. In 1916, when the war prosperity in the silk industry was just beginning and the demand for labor increased, the nine-hour day was won. Three years later a conference was called of the various trade unions in Paterson, which decided to press the demand for an eight-hour day. The bosses, with the memory of the 1913 strike still vivid in their minds, were unwilling to face another stoppage at that time, and granted the demand.

Up to 1920 there were four unions of silk workers in Paterson—locals of the United Textile Workers, the Amalgamated Textile Workers, the Industrial Workers of the World, and the Associated Silk Workers. None of them had any strength, but each had its own shop control here and there. Then came the aftermath of the war–a severe industrial crisis. Most of silk mills closed down. Workers were idle eight, nine, and ten months. Wages were slashed more than forty per cent. This practically destroyed whatever trade union organization had previously existed, but it also gave an impetus to the movement for one union of silk workers in Paterson. When the remnants of the various locals, excluding the United Textile Workers, united with the Associated, the first step was taken to end the chaos caused by the existence of separate local bodies, and to build a united) organization. Within a short time the Associated succeeded in organizing about thirty per cent of the broad silk weavers, and became a definite factor in the labor movement.

The New Revolt.

The struggle now being waged in Paterson is in many ways a second revolution in the silk industry which may well overshadow in results, if not in extent, the strike of 1915. It was precipitated by the gradual encroachment of the mill owners upon the standards won by the workers, and particularly by the rapid spread of the three- and four-loom system. Early this year the depression began in the silk industry which now marks textile manufacturing generally. Immediately an assault was made upon the laboring conditions of the silk mill weavers. Mill after began to introduce the multiple loom system. Many of them closed down for a month, and opened only on condition that the weavers agree to operate three or four looms instead of two.

What the workers had feared in 1918 had become a reality. The three and four-loom system had brought about unemployment, decrease in wages, longer hours. Its introduction necessitates no new machinery Shops operating on the two-loom system introduced the four-loom system by cutting their labor force in half and doubling the number of looms each weaver must attend. The result is an increase in the army of unemployed, with the consequent competition for jobs and the lowering of labor conditions, not to mention the greater nervous strain which menaces the health of the workers.

As an excuse for their attacks the mill owners claim they are becoming impoverished by the excessive demands of the workers. But while the average weaver earns the miserable wage of twenty to twenty-five dollars weekly, the silk manufacturers of Paterson build large annexes in other towns out of the riches amassed from the toil of the silk slaves. While whole families are forced into the mills in order to earn enough to meet the cost of living, the wealth accumulated in the business of silk production has enabled the silk barons to own and control the biggest banking houses of Paterson.

To resist the multiple loom system, to restore the eight hour day, to increase wages and force recognition of the union, the Associated Silk Workers union decided to call the broad silk weavers out on strike. Within two weeks over 10,000 workers were out and three hundred mills tied up. Eighteen nationalities are involved, chief among whom are the Italians, Americans, Syrians, Jews, Poles, and Lithuanians. A signal proof of the exploitation in the silk mills of Paterson is given by the Syrians.

Brought from other towns to scab in the strike of 1913, and later the backbone of the three- and four-loom system, they are today the most enthusiastic supporters of the strike and the most bitter enemies of the silk manufacturers.

The Government Versus the Workers.

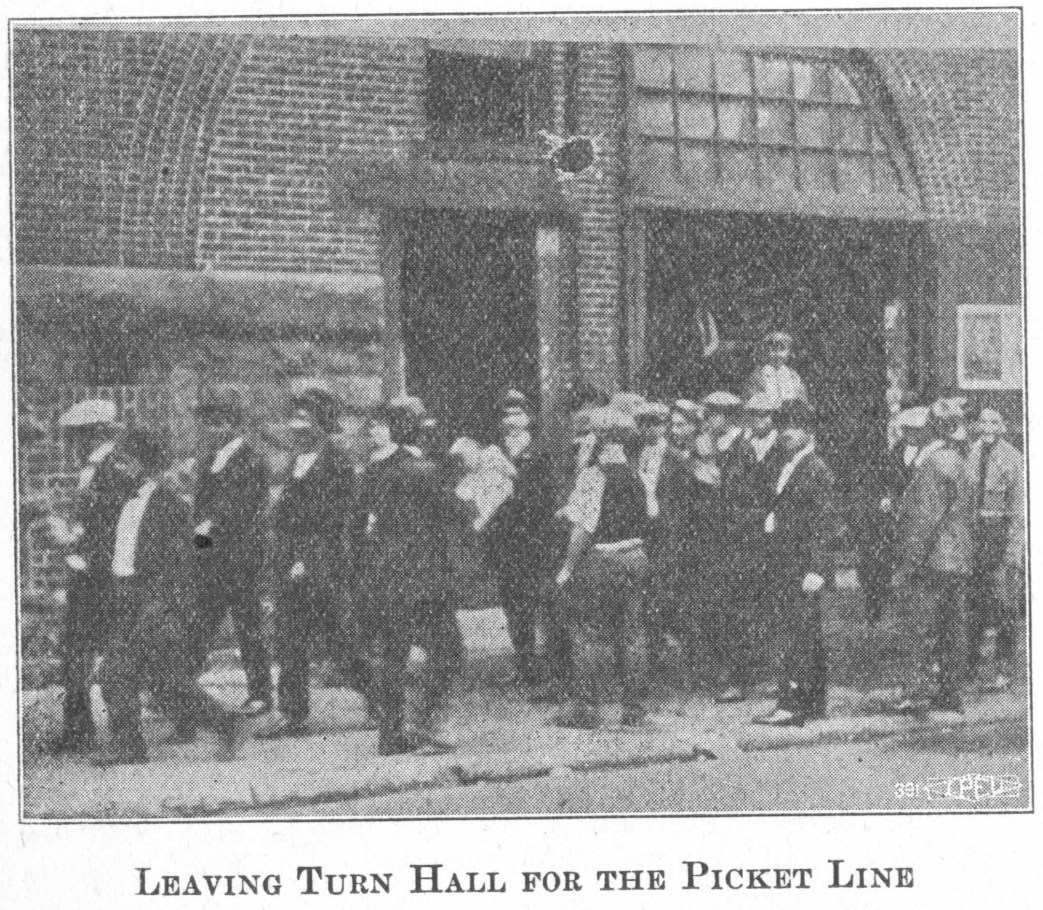

Throughout the strike the silk workers have seen how class government functions. Though this strike is the most peaceful ever conducted in Paterson, police terrorism has been rampant. Weavers on picket duty have been subject to arrest from the beginning. On one occasion 107 strikers, following out the union policy of mass picketing, were arrested in a body while they were quietly patrolling the streets before one of the mills most bitterly opposed to the union, Blanket injunctions have been obtained by the leading silk manufacturers of Paterson forbidding the strikebreakers to leave the employment of the firm either at their homes or on the streets. Turn Hall, historic meeting place of the Paterson silk strikers, has been closed by the chief of police, as it was closed in 1913. All the so-called American rights of free speech and assemblage have been violated by the public authorities who are backing the silk manufacturers today, as they have done in previous strikes.

in answer, the strikers have adopted a policy of defiant resistance. An outstanding feature of the strike, and one which makes this struggle especially important for the labor movement, is the fact that mass picketing has continued, despite injunctions. For the first time, striking workers have in a body disregarded this infamous weapon used by the owning class in their war against labor. The silk weavers of Paterson have not merely talked—they have acted. The day after the decision was taken to go on with picketing, over a thousand silk workers encircled the mill that had obtained the first injunction, giving a splendid demonstration of militancy. In thus violating the injunction, they set an example for the entire working class. Their heroic stand has deterred the courts from taking definite action against them; for while picketing of “injunction shops” continues, few strikers have been arrested for contempt of court, and hearings on their cases have been constantly postponed.

Virile Fighting Forces.

The spirited determination shown by the strikers to see the fight through at all costs has been due to the influence of those workers who are members of the Trade Union Educational League and the Workers Party. From the very first day of the stoppage the League militants have been in the front ranks of the strike. Communists are found on all the principal committees, helping to shape policy and direct activity. It is their voice which encourages the workers to mass picketing, and arouses the enthusiasm of those battling against the silk magnates.

To divert attention from the real issues of the strike, the silk manufacturers, together with the Paterson Chamber of Commerce, the chief of police, and the kept press of the city, have seized upon Communist activity in the strike to raise the cry of red menace, hoping thus to intimidate the workers. They have sought to demoralize the strikers by threatening to drive out of town all “outside agitators” meaning the Workers Party speakers who have been the most influential factor in keeping intact the ranks of the striking weavers. This campaign of the capitalist masters of Paterson, however, has failed of its purpose. The Communists have won the confidence of the silk weavers by their loyal service in the struggle. Attacks against them have but served to open the eyes of the strikers to an understanding of class rule.

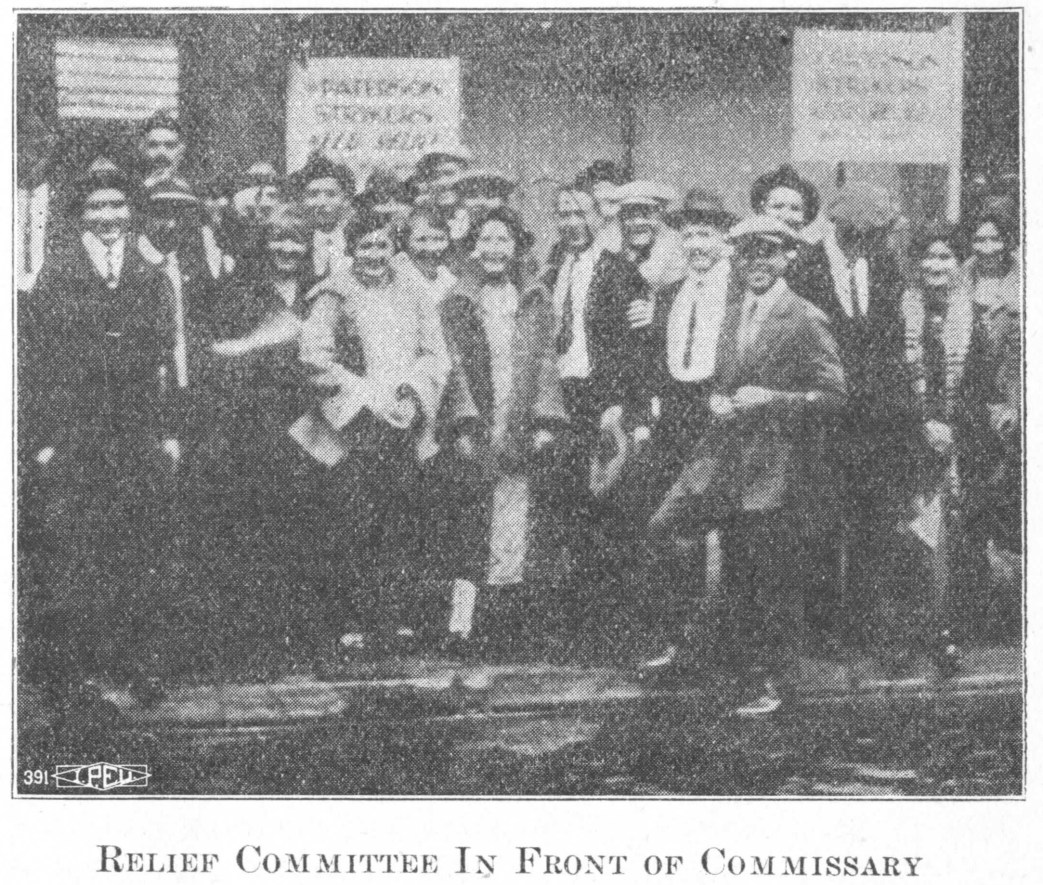

The strike has been in progress for two months. About the silk manufacturers, together with the Paterson Chamber meets with the union, conceding all the demands. What the final outcome will be, however, it is impossible to predict at this writing. The strike committee, anticipating an extended conflict, has organized relief machinery, established a food commissariat, and sent appeals to labor bodies. In this relief campaign, the Workers Party and the Trade Union Educational League have actively participated. They have organized a relief committee of their own which sent a thousand dollars to the strikers within a week after its formation. Their work is being intensified, and relief committees are being organized in other cities.

So far, the strike has been successful. The weavers who have returned to work under agreements signed with the mill owners who have won an increase in wages and the restoration of the eight-hour day. The union has obtained shop control over each of the settled mills, all the workers of which, regardless of craft, are organized in the Associated. More significant, however, as an indication of the value of this strike, is the fact that the task of organizing the silk workers has assumed primary importance.

Divisions Must Be Abolished.

Experiences of the last fifteen years have been gradually impressing the silk workers with the need of establishing one union in the silk industry. The present strike has deepened that conviction. In Paterson the only force capable of carrying on organizational activity among the silk workers is the Associated Silk Workers union. True, there is also a local of the United Textile Workers, but this has only a few hundred loom fixers, quillers, and twisters—the labor aristocracy of the silk industry. This A. F. of L. organization bitterly opposes the Associated, and has even sent instructions to all unions affiliated with the American Federation of Labor not to support the appeal of the strikers for relief. Such opposition has not weakened the Associated. By its work it is winning the support of the silk workers. Its prestige has been greatly strengthened by the strike, and it plans to carry on an organization campaign to keep the few thousand weavers now affiliated with it when the struggle is over.

This alone, however, will not solve the problem confronting the silk workers. The great need which exists today for all the workers engaged in manufacturing textile products, whether cotton, silk or worsteds, is the amalgamation of all the unions within the textile industry. An end must be put to the division within the ranks of labor itself. Whatever the gains of the present Paterson strike may be, the silk barons will again attempt to wrest them away at the first opportunity. An effective resistance can be made only by consolidating the forces of the workers in the entire industry.

The militant silk workers organized in the Trade Union Educational League and the Workers Party will carry on an agitation for amalgamation, recognizing in this the most vital task before them. In the present strike they have made clear to the strikers the nature of the class struggle. They have awakened the class consciousness of numerous silk toilers by exposing the capitalist dictatorship as it exists in Paterson and throughout the country. So also they will continue to battle for unity of the labor organizations in the textile industry, thus making possible a unified drive to organize the unorganized, and forging a weapon with which to fight exploitation in the textile industry all along the line.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/wm/1924/v4n01-nov-1924.pdf