‘The Japanese Miners’ by Sen Katayama from the International Socialist Review. Vol. 11 No. 8. February, 1911.

THE Shogun of Japan is chief general of the Empire. How the Japanese miners secured many rights and privileges from the Shogun Iyeyasu is worth the telling. The story goes that in a time of war Iyeyasu, the future Shogun was beaten in battle, traced and followed by the enemy far into the mountains.

And Iyeyasu came up to the gates of a mine and asked the miners to allow him to enter so that he could conceal himself. But it was not customary for the workmen to allow anybody to enter the mines except the miners and they refused Iyeyasu in spite of his urgent pleas.

Then, the story goes, Iyeyasu made an attractive offer. He promised that if he should ultimately be able to defeat his enemies and become a lord over Japan that he would make all miners Nobushi, with special privileges and free passes all over Japan.

The miners were much impressed and at last decided to conceal Iyeyasu in the mines from those who made the attack.

So Iyeyasu escaped death and became final victor. All this happened years ago in the Hikagesawa Mines in Sarugas Province at the foot of the Fuji Mountains.

When Iyeyasu established his feudal government over the whole of Japan, the constitution he gave contained fifty-three articles, among them one which gave the miners of the Empire the privilege of wearing two swords and of calling themselves Nobushi, Field Knight or Open Samurai. This gave the miners of Japan a strong union and many privileges.

Under Old Japan

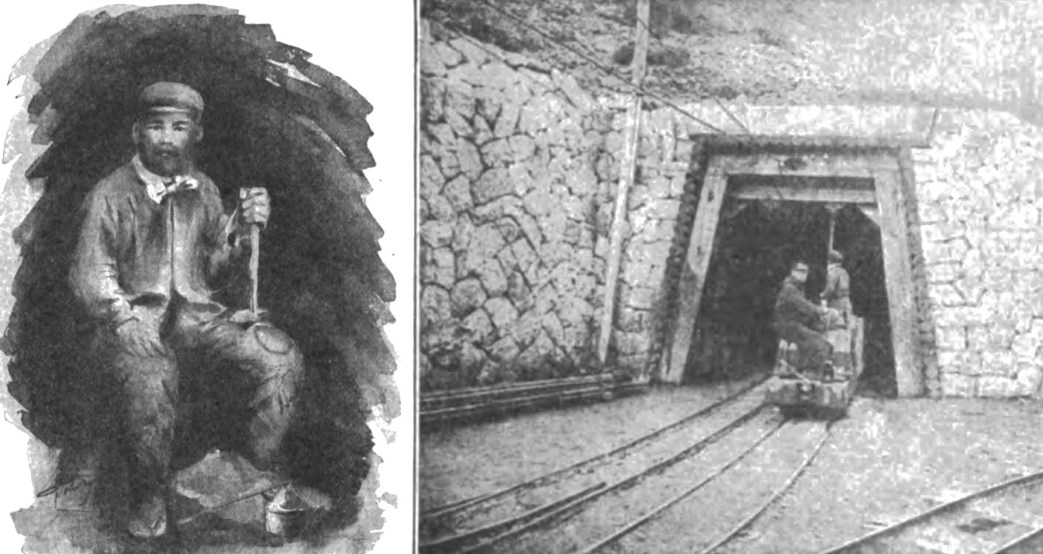

At the time of Feudalism, in Japan, the gold and silver mines were worked by the government and very few belonged to private capitalists, so that it was not such a difficult thing for a powerful government official to bestow many favors upon the miners. Methods of mining were primitive and the men had to undergo many hardships and lived lives of constant danger. Miners were supposed to be the cream of courage in the Empire, men who feared Death not at all. Wages were very high. “Kanayama Shotai,” a miner’s living, is even today used as a synonym for luxurious living among the working class. Inside the mines the men lived as they chose. There they ruled absolutely and there were no restrictions put upon them. In the great chasms of the earth they made laws and rules of their own.

Few men had households of their own. Nearly all lived communistically in a hanba, all families living together to make the work easier. This hanba is still maintained by miners in all the unions. A head of the hanba is elected by majority vote and has much influence and power.

Practically there has been but one miners’ union in all Japan. As a miner, each man is welcomed as a brother to any mine in the Empire. For example, a miner comes to a strange hanba. The men and women receive him with ceremonies and treat him, at once, as a member and brother in the great union. If there is no work, or the guest is on his way to a distant mine, he is welcome to stay a few days when a miner from the hanba escorts him to his new working place. A miner in good standing in the union could formerly travel from one end of Japan to another under the care and guidance of his brother miners. Their strongest watch word is Mutual Aid. But all this was not enough to protect them in their struggles with the invading mine-owners.

For advancing industry and the introduction of Western mining methods have wrought a great change. Thousands of new mines have been opened for the production of baser metals. The coal mines have become a source of great wealth to the new owners, so that the Miners’ union has been materially altered.

Almost every farmer, who has little work to do on the farm in the winter, comes to the coal mines for work at that season.

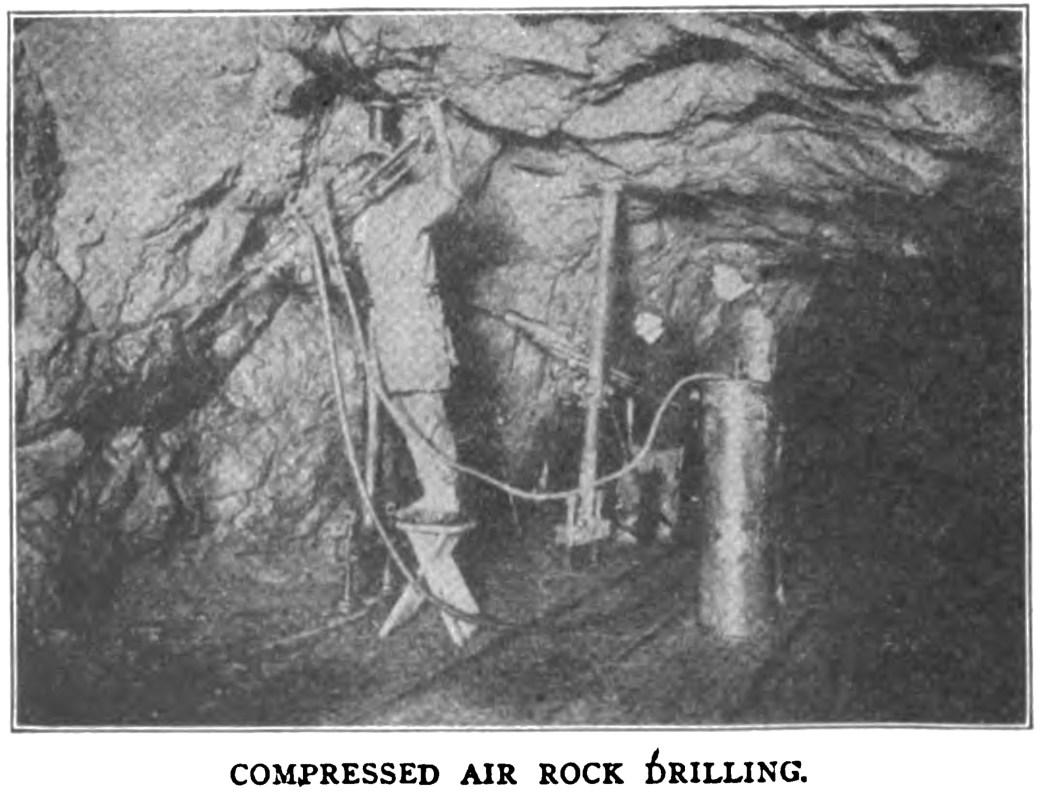

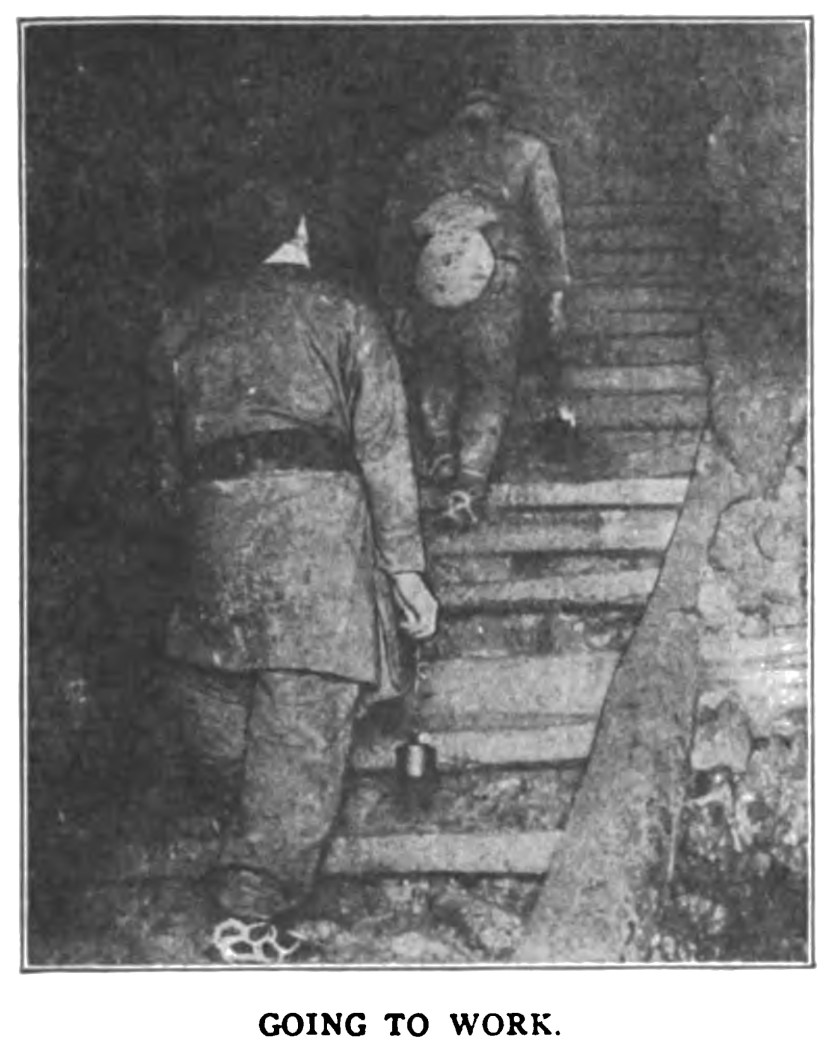

It was the wonderful Western Shaft System that deprived the men of their underground kingdom. ‘Their rule is gone. These men are now lowered by shaft, run by electric power or carried in by electric railway cars. And the Boss has come. to stay. Miners must obey his rules and work under his supervision. The company weighs his product and pays what it deems sufficient. The luxurious living of feudal days is gone.

But the men still cling to the old forms, electing their head and clustering about the old union ceremonies. And all the efforts of the mine owners have not yet been able to destroy the organization.

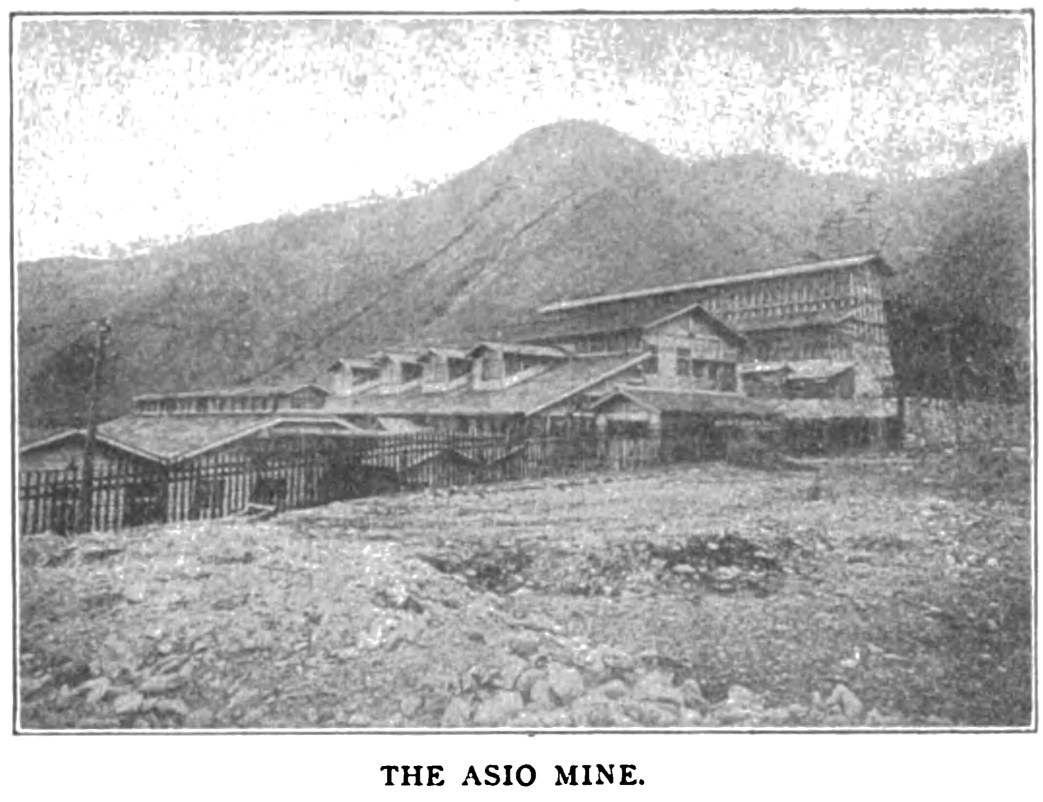

The Asio Copper Mine

The Asio Copper Mine is known all over the world for its wonderful copper ore. It is owned by the Furukawa family, which has made huge fortunes out of this and other mine holdings. Furukawa, the original owner, is now dead. His son leads an easy life, enjoying the wealth the miners dig for him. The most important thing known about him generally is that he paid $50,000 for a dog.

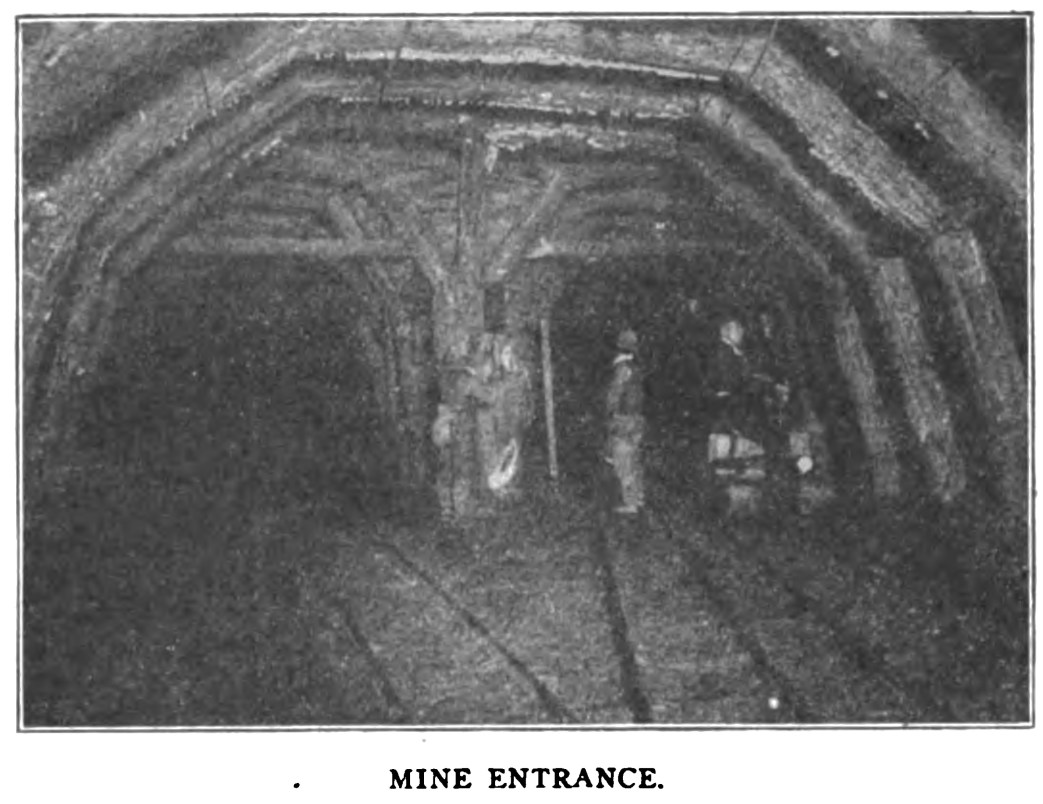

Asio is 120 miles from Tokyo and fifteen miles from Nikko Temple, figuring straight over the mountain. Freight from the mine is carried over the mountain by cable carriages run by water power. Nearly 7,000 miners are employed in Asio.

Four hundred carpenters prepare the arches and props where the 3,000 copper miners work. Over 250 women and girls work outside the mines at various jobs.

Labor Trade in Asio Mines

In every mine in Japan there are twice or thrice as many workers as there are miners. These are “common labor” recruited from any quarter. Gradually the miners themselves have come to be recognized as the most exploited workers in Japan. Men are now enticed into the mines by promises of a good living and many kindnesses, as no intelligent man wants to work in a mine. But when workers are recruited under false pretenses and once enter the Asio mine, they are treated almost like slaves—particularly the unskilled laborers, While the miners in the old organization are still able to demand decent living for themselves, the unorganized workers are almost as bad off as galley slaves.

In order to prevent these men from leaving the mines, the bosses keep them in continual debt. Men cannot leave the mines in the day time and the only chance for escape is’ during the night. But the mines are usually far off from the cities in the mountains and the roads are patrolled by policemen or guards so that the runaway is often caught and brought back.

The old hanba was the real headquarters of the miners, but it has evolved into a tool for the mine-owners. It is still nominally the communistic dining hall or home, but is now used for exploitation and enslaving the men by debt.

It is his debt to the mine-owner that hangs like a yoke about the neck of the miner and forces him to work long hours for a pittance.

Girls and Women in the Mines

In Asio we see so many women and girls at work that we are unable to distinguish whether they are men or women. These women and girls are employed by a sub-boss, not directly by the mine company. According to Japanese mining laws, the mine-owners must pay a certain wage scale, but there is a vast difference between the law and the facts. Asio is a mining town. There the power and influence of the mine master is absolute. Public authority and the police are all serving the mine-owners. The mine-workers have no protection from the greed of the company.

My Shabsai Shimbun is sent to the miners. It is confiscated by the mine owners and never reaches them. Evidently the mine masters can do as they please and open the mail.

Since the riot of 1907 it has been impossible to work outside for the miners. This makes it worse for them, but we hope that some day we can work openly for them!

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v11n08-feb-1911-ISR-gog-Corn-OCR.pdf