A very early look at the workers movement in Puerto Rico from when the United States took over the Spanish colony by John Spargo for the inaugural issue of his ‘Comrade’ magazine.

‘The Socialist Movement in Porto Rico’ by John Spargo from The Comrade. Vol. 1 No. 1. October, 1901.

The story of the Socialist movement in the Island of Porto Rico covers only a brief period of time, less than a decade, but it is full of interest and heroic deeds. The annals of the great world-wide Socialist movement abound with instances of oppression met by devoted self-sacrifice, but nowhere to greater extent than in that unhappy little island, alike under its Spanish and American rulers.

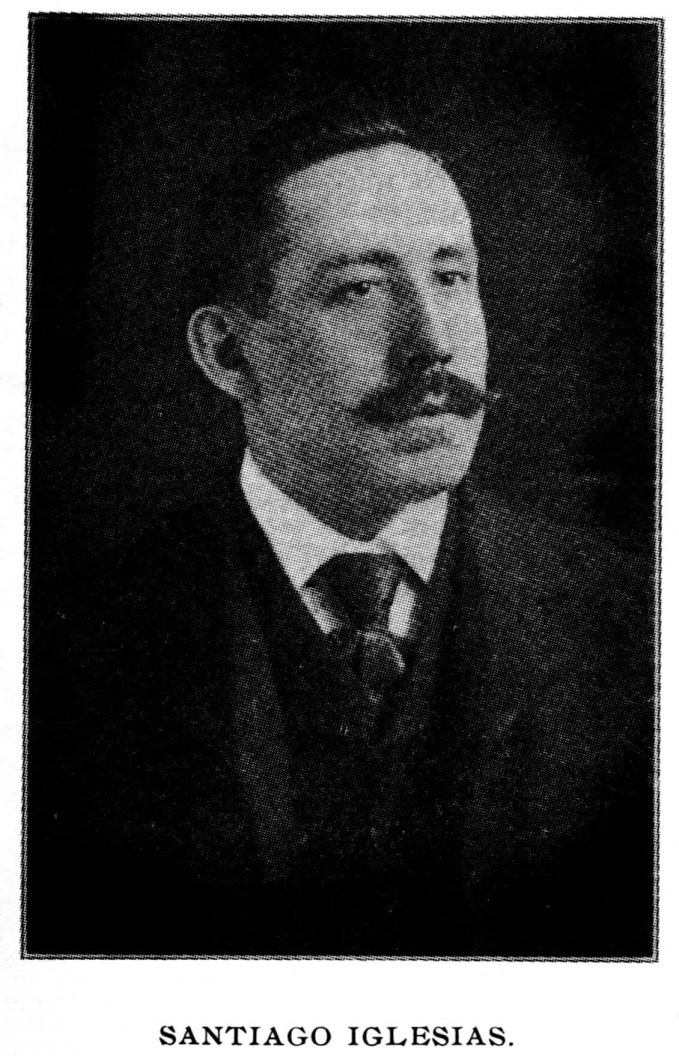

In 1894 Santiago Iglesias, who had been converted to Socialism years before in his native land, Spain, moved from Cuba to Porto Rico, intent upon spreading there the principles of Socialism. Three times before he had made the journey, but never with such an important mission. For more than two years he labored, almost alone, and then on May Day, 1897, the first visible sign of success appeared in the form of a newspaper, edited by himself, called the “Ensayo Obrero.” His first associates were Ramon Romero, Jos-e Ferrer y Ferrer, Fernando G. Acosta and Eduardo Conde. Ferrer was the first to suffer persecution at the hands of the Spanish authorities, being sentenced to two months’ imprisonment for a caustic article in the “Ensayo Obrero” against the Civil Government. Iglesias was the next to suffer, being arrested and imprisoned without trial no less than three times during the next few months upon various pretexts.

In March of the following year, being afraid of the effect of the Socialist agitation, and in view of the near approach of the elections, the authorities decided to imprison all the leading Socialists. Accordingly the officers called at the office of the paper to arrest Iglesias, but he escaped and was not captured until a month afterward, when he was thrown into prison, remaining there until the formal occupation of the island by America in October, being then released by General Brooke. By some it was thought that under American rule there would be greater freedom to agitate and build up a political party than before, but, alas! For such hopes. Just as they had been oppressed by Spanish, they were now oppressed by their American rulers.

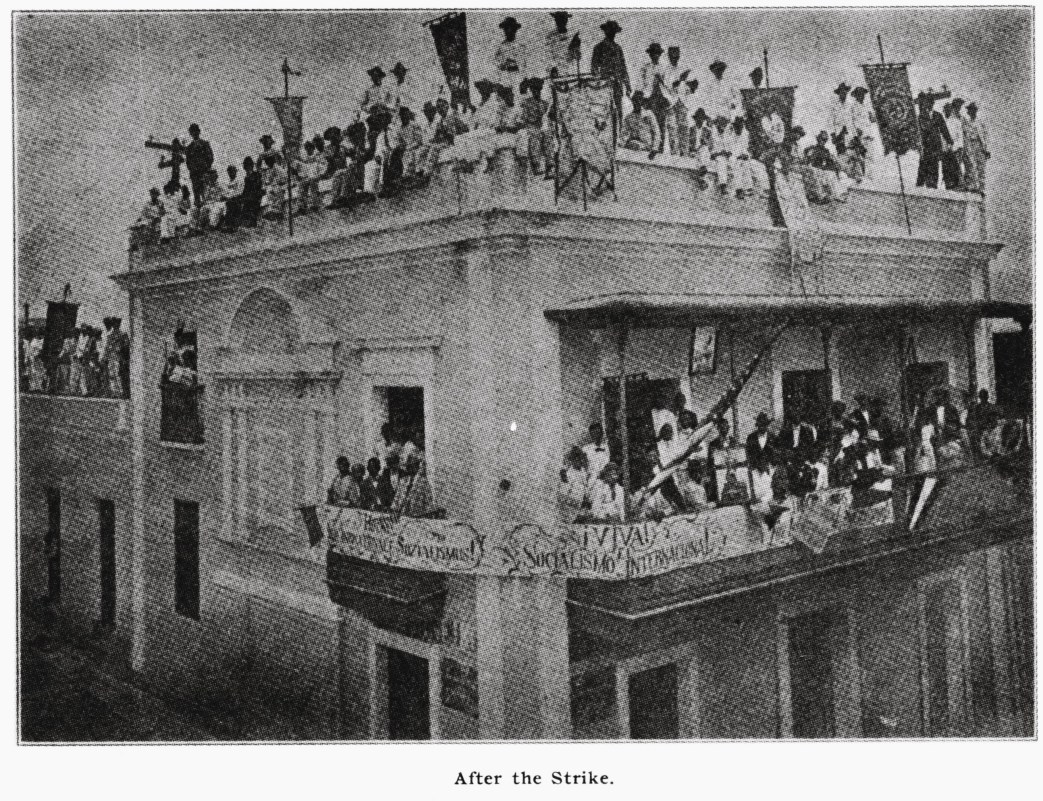

After the strike. pressed by American rulers. Their meetings were broken up, and just as the ”Ensayo Obrero” had been suppressed by the former, so its successor, “El Porvenir Social,” was suppressed by the latter; and when Iglesias and others issued a protest they were imprisoned. Iglesias often tells of an interview between General Brooke’s secretary and himself. The secretary said: “You are provoking revolutionary agitation, and it must cease. Either you must stop this sort of thing (pointing to the ‘Manifesto’ protesting against the action of the authorities) or we will stop you.” And in vain did Iglesias plead constitutional rights.

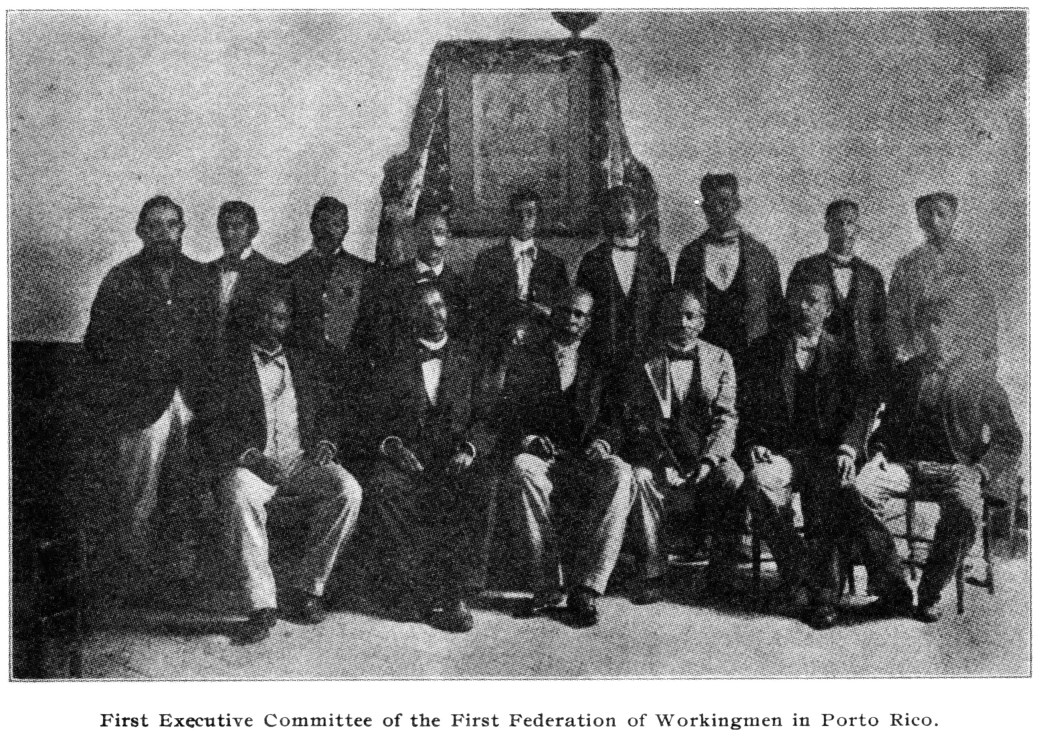

But the “Federation Libre” which had been formed soon after his release from prison in October, 1898, was growing apace in spite of everything. In 1900, owing to a reduction in wages consequent upon the change of currency from Spanish to American money, there was a general strike in all industries, when the Government outdid their Spanish predecessors. All the members of the executive of the Socialist party and of the trade unions were arrested and put in jail, but in spite of all this the workers made considerable gains. In Porto Rico the trade unions are largely Socialist and most of the prominent officials belong to the Socialist party.

Soon after the strike the elections took place, but there was only one party-the Republican-admitted to the official ballot. The Federal party, composed mainly of business men opposed to Government from outside, and the Socialist party both applied to be placed on the “ticket,” but were denied that “privilege,” being told that “the Republican party is good enough for Porto Rico,” in spite of the fact that out of sixty-six municipalities the Federals held forty-four and the Republicans only twenty-two! Such is American Liberty in Porto Rico!

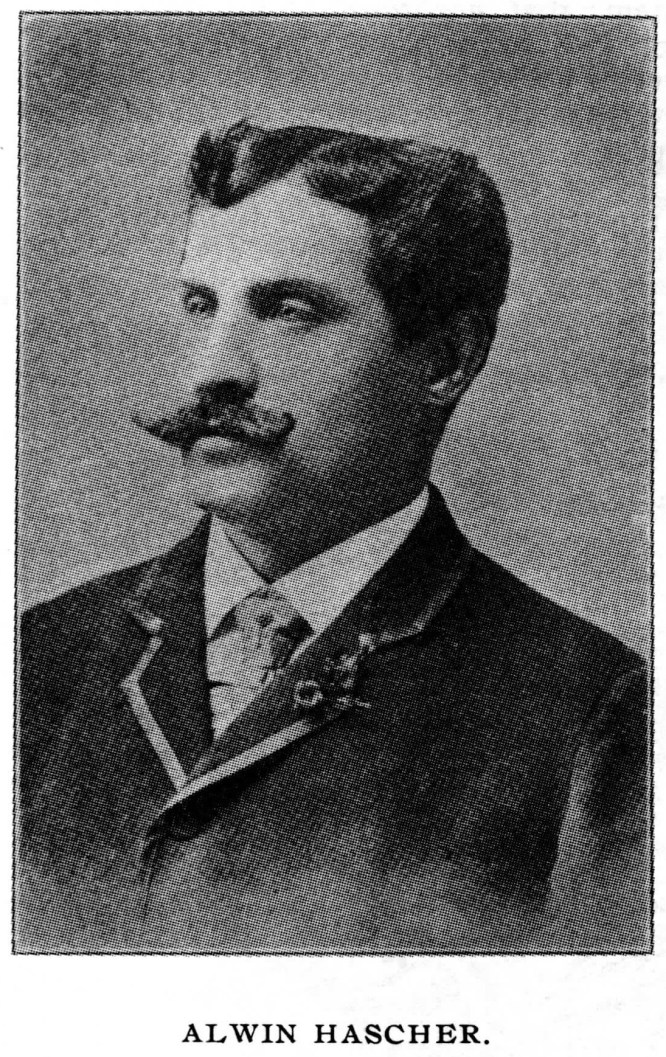

Some time ago two comrades Hascher, a German, and S. Raines, an American-were sent to prison for protesting against the cruel treatment of workmen in the prison at San Juan, and recently Hascher was clubbed in the streets while reading a protest against the same inhumanities. But notwithstanding all obstacles the movement grows. This is the day of its trial and suffering-the day of its triumph will come, and is nearer perhaps than we think. Speed the day!

The Comrade began in 1901 with the launch of the Socialist Party, and was published monthly until 1905 in New York City and edited by John Spargo, Otto Wegener, and Algernon Lee amongst others. Along with Socialist politics, it featured radical art and literature. The Comrade was known for publishing Utopian Socialist literature and included a serialization of ‘News from Nowhere’ by William Morris along work from with Heinrich Heine, Thomas Nast, Ella Wheeler Wilcox, Edward Markham, Jack London, Maxim Gorky, Clarence Darrow, Upton Sinclair, Eugene Debs, and Mother Jones. It would be absorbed into the International Socialist Review in 1905.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/comrade/v01n01-oct-1901-The-Comrade.pdf