Louise Thompson was among the most important early Black women Communists in the U.S. and a leader of Scottsboro and Party work in Harlem during the 1930s. She would later marry William L. Patterson, Secretary of the International Labor Defense. Thompson the writer-activist was a witness-participant in one of the events that defined the Harlem of that era, the so-called ‘race riot’ of 1935. A rebellion against police brutality, it was a scene so often repeated since. Yet it was in stark contrast to most big city ‘race riots’ of that time, pogroms against isolated Black ghettos, and marked the growing confidence, and militancy, of Northern Black workers.

‘What Happened in Harlem: An Eye-witness Account’ by Louise Thompson from New Masses. Vol. 15 No. 1. April 2, 1935.

ABOUT five o’clock on the afternoon of March 19 a small group of people were gathered in front of the Kress Five and Ten Cent store on 125th Street in Harlem. Inside, near the doorway, stood another small group. Though there seemed to be little excitement, it was evident that something had happened and I stopped to ask one man in the crowd what was going on inside the store. He didn’t know, but like the rest of the group was waiting to find out what it was all about. I entered the store.

Most of the girls behind the counter were still in their places but no floor-walkers or officials were in evidence who might have given an explanation why the little dusters of people were standing here and there in the store. I approached one woman who was standing quietly by the candy counter and asked her what it was all about. “I don’t know,” she said. “They say some kid was beaten up when they caught him trying to steal a piece of candy.” I approached another group, in the midst of which was a tall, handsome Negro woman engaged in a heated conversation with a Negro man. She seemed to be remonstrating with him.

“What’s up?” I asked. “A little colored boy was beaten up by a sales-girl and the manager of the store,” she replied. “What are you doing now?” I continued. “We are going to wait right here until they produce that boy,” she replied. “Yes,” said another woman of slight build, who stood holding two large sofa pillows she had just purchased in the store, “we’ll wait here if it means all night.”

So they stood waiting, patiently, quietly. The tall, dark woman scolded some small Negro boys who began to scuffle with each other. “Hush, you all I” she said. “Stop your foolishness. Don’t you realize a colored boy’s been hurt?” The group continued to wait, but as they waited patience began to give way to indignation. Their voices rose. They demanded that the manager produce the injured boy.

“She didn’t have no right to touch that boy,” said one woman in the group, “and you know that white man wouldn’t have kicked no white child.”

“No,” said the tall, dark woman. “Just think, it might have been my child-it might have been any of your children. And, to think, he may now he dying, just for stealing a little ole piece of candy. I’m going to stay right here till they bring that boy out and he better be all right, too.”

About this time a few policemen began to filter into the store. At first they did not approach the group standing near the candy counter. They walked back into the store, evidently to get “their orders.” Then they came back and approached our group.

“Come on, now, move along. Get out of here,” said one.

“I ain’t movin’ nowhere until they produce that child,” answered the woman.

Just then a woman screamed in the back of the store and the crowd surged forward, the tall woman in the lead. The cops drove them back toward the front of the store. The tall woman was the last to leave. The cops began to get rough. In retaliation one woman took her umbrella and knocked over a pile of pots and pans. Simultaneously, dishes began to be broken, glasses were knocked to the floor, a few more screams were heard, mingled with the closing bell of the store. The more timid hurried out into the streets. The more aggressive stayed behind refusing to move until they got some information about the boy. The cops formed a ring at the door to keep out the rapidly gathering crowd on the sidewalk. The women inside refused to budge and stood by their leader, the tall woman with the umbrella in her hand.

“Don’t you realize a colored child’s been hurt, he may be dying, and we can’t find out nothing about him?” the tall woman said.

“Get out of here,” shouted the policeman. “What the hell can you do about it? Go on home before you get into trouble.”

Immediately a chorus of women’s voices answered him, stridently, indignantly. I approached one of the policemen. “Can’t you give us some explanation,” I asked. “Surely these women are entitled to know if the boy is injured and where he is.”

“If you know what’s good for you,” he replied, “you’ll get on out of here. What do you suppose we’re here for? We’ll take care of the kid.”

“Yes, you’ll take care of us just like you do when they lynch us down South,” a Negro woman answered. “We’ll take care of our own. I’m a mother. It might’ve been my child. Colored folks don’t get no protection nowhere, in New York or down South.”

They began to shove us out of the store. The last to leave was the tall, dark woman. A cop threatened her with his night-stick. “Hit me. Go right on and hit me,” she challenged, clutching her umbrella all the firmer. The cop lowered his night-stick. We moved toward the door. By this time the crowd had grown into a huge mass, pushing forward to find out what was happening.

As we backed into the street, we heard the clang of an ambulance. The crowd became tense. An interne with his bag hurried into the store, escorted by a number of cops who completely blocked the entrance behind him. In the street, I had my first opportunity to look about. The crowd before the store had swollen to hundreds. Across 125th Street stood thousands. Shrill sirens of police cars. Increasing excitement. I was pushed toward a tall Negro woman. We simultaneously locked arms. A woman approached us. “He’s dead,” she shrieked. “What do you mean?” asked my companion. “Who’s dead?” “The boy,” she replied. “How do you know?” I asked. “Somebody saw them carrying him out just now on a stretcher with a sheet over him from the 124th Street entrance of Kress’s.”

My companion was beside herself. “Dead,” she said. “Oh, no, you don’t mean that. He can’t be dead. No, he can’t be dead jus’ for stealing a piece of candy.” “Yes,” replied the woman. “You know that two ambulances drove up here and they didn’t take nobody away. Now they have taken him away with a sheet over him on a stretcher.”

The rumor spread like wildfire. We walked toward Eighth Avenue. Everyone was saying that the child was dead. Whenever we stopped for a moment, the cops would rush us. “Move on, there! Move on!” We reached the corner, and were quickly surrounded by a group, only one of the many groups that now choked 125th Street between Eighth and Ninth Avenues.

We walked along the street to Seventh Avenue, urging the people to follow us, telling them to keep their heads, advising them to keep away from the cops who were becoming ugly in their attempts to break up the increasing throngs of people. On Lenox Avenue we stopped. There were only three of us, I and two of the women whom I had met in the store, my tall friend and another woman who had remained in the store until the last. We went into an office of a friend. Small groups of Negroes began to filter in to find out what it was all about. Others, on learning the facts, were all for smashing up the store. We reasoned with them that this would do no good. If the child were dead we must demand that the authorities prosecute the guilty parties and at the same time take steps to prevent other Negro children from receiving the same fate.

We went back to Kress’s. By this time crowds were swarming the street, worked into a feverish pitch of excitement by all sorts of rumors. The resentment of the people had widened beyond indignation about the boy. “We ought to close up every damn store on 125th Street,” said one man. “This ought to make the colored people wake up and do something against these high rents and high prices for bad meat and food we are charged in Harlem,” said another. “Yes,” said one member of a group who had picketed 125th Street last year demanding jobs for Negroes, “you women wouldn’t listen to us last year when we told you not to trade in these stores unless they gave us jobs. Maybe you’ll learn some sense now.”

We finally worked our way through the crowds back to Kress’s. As we approached the store, we saw a young Negro set up a ladder in front of the store. He climbed the ladder and began to speak. It was difficult to hear him, few members of the crowd stopped talking to listen.

The young man on the ladder continued to speak. I was able to gather that he was for “Negro and white solidarity against police-provoked race-rioting.” When he had finished, a white man climbed up to speak. He had scarcely begun when there was a crash. From somewhere in the crowd the first stone was thrown to break the window of Kress’s store. Quickly the small crowd about the speaker was broken up, the speaker jerked down, ladder and all, by the police and arrested. We scattered, and I lost my companion.

The so-called “race riot” in Harlem had begun.

In a few minutes all the windows on 125th Street, Harlem’s shopping district, were smashed. Anger and resentment swept like wildfire through the streets massed with Harlem’s starving thousands. Young men took radiator caps from cars parked along the street and hurled them through plate-glass windows.

Whole detachments of bluecoats arrived on the scene and set to work. Brigades of mounted police cantered down the street, breaking into a gallop where the crowds were thickest. Horses’ hoofs shot sparks as they mounted on the glass-littered pavements. The crowds fighting doggedly, gave way. The women more stubborn even than the men, shouted to their companions, “What kind of men are you-drag them down off those horses.” The women shook their fists at the police. “Cossacks! Cossacks!” they shouted here in Harlem on 125th Street.

A policeman charged at a boy on the pavement. “Get on there. Move on-move on,” he raised his night-stick. The boy stood there stubbornly marking time, his feet moving up and down but he did not give way an inch. The police forces grew. They sweated and grunted, ploughing their way through the crowds for an hour. The repeated charges of the mounted police began to scatter the people. About nine o’clock the masses began to give way, dispersing up the side streets. Just as the crowd seemed routed, another group broke through the police cordons, swept down to Kress’s once again. Few windows remained intact in the store.

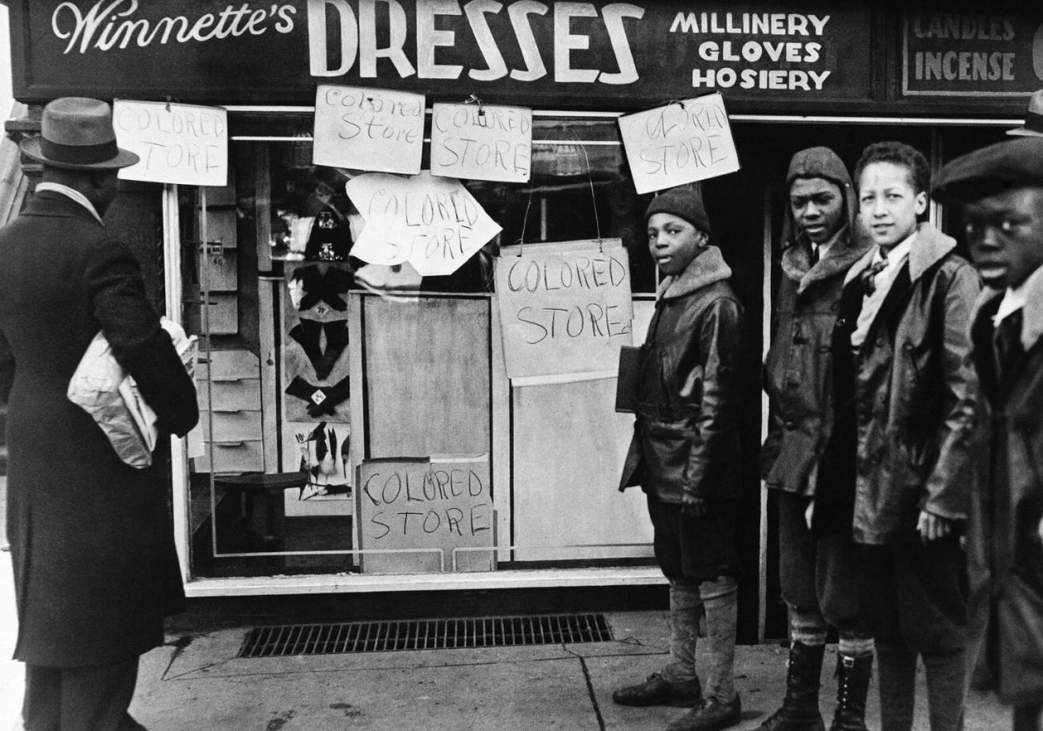

Every plate-glass window from 116th to 145th Streets was smashed. The only ones spared were those with signs posted “Colored shop” or “Colored work here.”

Many grocery store windows were smashed; hungry Negroes scooped armloads of canned goods, loaves of bread, sacks of flour, vegetables, running to their homes with the food. On Seventh Avenue workers tossed sacks of flour up to their companions leaning out of the windows from the floors above.

The long green riot cars of the police department began to converge from all directions. Shots were heard. Cops appeared in the middle of the streets with their guns in their hands. Plainclothesmen, their hands on their holsters, passed up and down the streets trying to drive the people into the doorways. The moment the police passed, they were out again. This all went on until dawn.

The early editions of the morning papers brought the workers of Harlem the first information about the boy who “started the riots.” They said his name was Lino Rivera-a sixteen-year-old Porto Rican boy. They pictured him, whole and smiling, in the protecting embrace of a Negro policeman. According to the papers he had stolen a knife from the counter of the Kress store. He was, they said, threatened with a beating. They admitted that much because bystanders overheard the store detective’s threats. “I’m going to take you down to the basement and beat hell out of you.” That remark was heard by several persons nearby. Instead, however, according to the press, he was taken to the rear door and turned loose.

I spoke with a woman who was in the store when the detective grabbed the boy. She told me the boy was about ten years old-not a sixteen-year-old boy as the newspapers reported. She said he was “a little black child.” Lino is sixteen years old-tall for his age.

I also spoke with another person who was in the store-a certain Mr. Brown. He corroborated the woman’s description.

Harlem is not yet convinced that Lino Rivera is the boy.

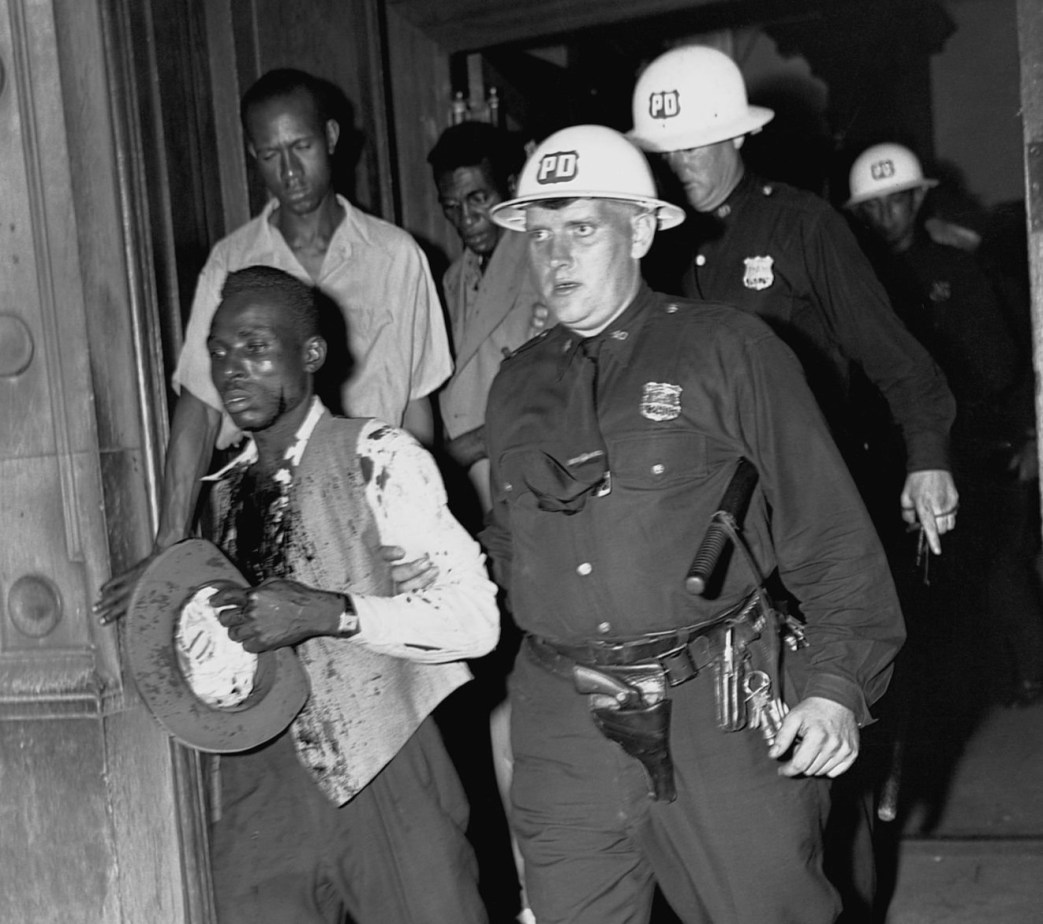

By dawn, one man, James Thompson, had been shot to death, taking food from a grocery store. Two more had been mortally injured. Over a hundred wounded. One hundred and twenty were in jail. Negroes were given the third degree on the way to jail and in the cells. Dicks shoved their captives into cars and beat them with blackjacks.

But many workers in Harlem ate hearty that morning for the first time in months.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s to early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway, Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and more journalistic in its tone.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1935/v15n01-apr-02-1935-NM.pdf