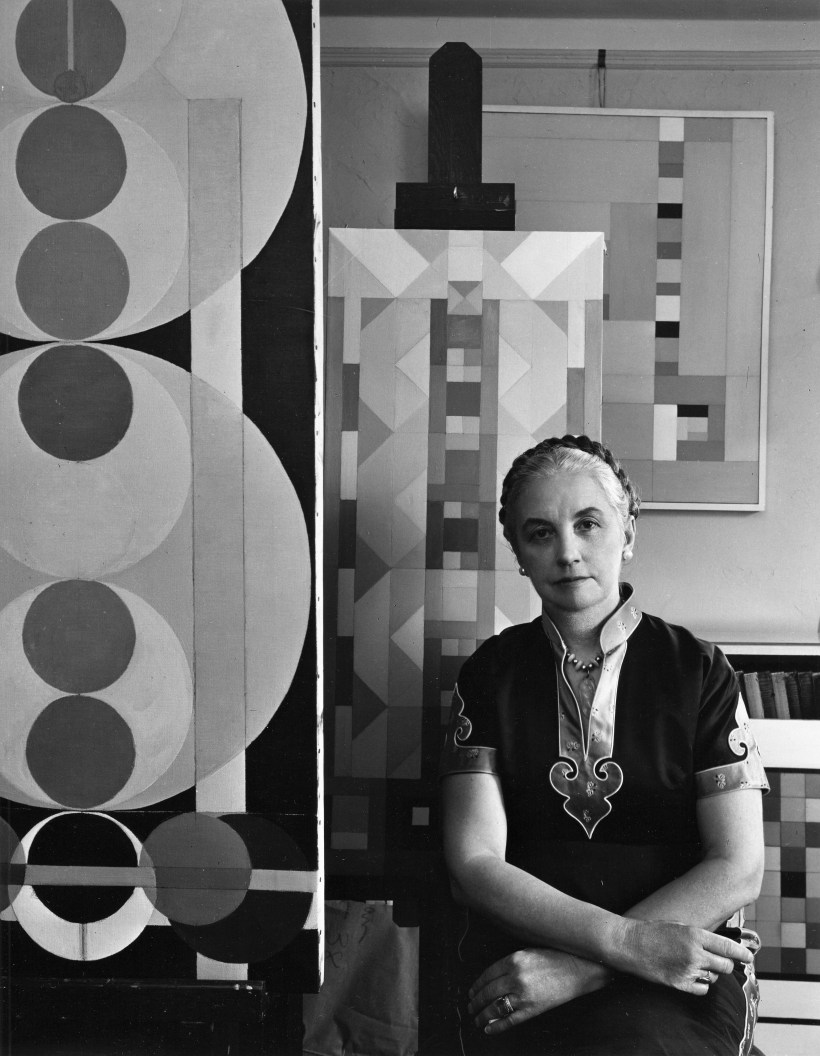

Marxist arts critic Charmion von Wiegand surveys the work of Ernst Toller.

‘Ernst Toller- The Playwright of Expressionism’ by Charmion Von Wiegand from New Theatre. Vol. 3 No. 8. August, 1936.

The publication in English of seven plays by Ernst Toller, the revolutionary German playwright now in exile in England, is of particular moment in America today. Both in form and content, these plays are bound to exert an influence on the American theatre, particularly the new theatre.

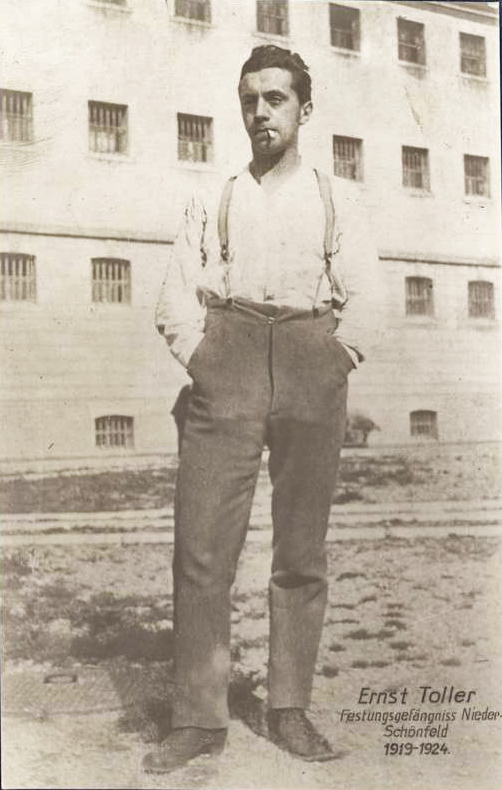

Ernst Toller is a German intellectual who fought in the World War and returned home sufficiently disillusioned with the old order to espouse the revolution in Germany. He took a leading part in the Bavarian uprising of 1918 led by the radical socialists, anarchists and communists, which was put down in cold blood by the German reactionary generals. Brought to trial in Munich for high treason, the left leaders were executed or sentenced to long terms of imprisonment. Toller received a five-year sentence.

From his cell in the fortress of Niederchonenjeld, Toller issued the manuscripts of several books and plays. Three of these plays-Massemensch, Der Deutsche Hinkemann and The Machine Wreckers were to have a tremendous vogue throughout Germany. They were written under the most difficult conditions, under stringent prison humiliations. Forbidden lights at night, Toller concealed a candle under the table and hidden there from the guard’s prying gaze he poured out his ideas in dramatic and poetic form. The secret night vigils, the stealthy haste of composition, the turbulent eagerness to express and clarify his thoughts, the cruel isolation, the passionate hatred of the old society, all influenced his style and moulded it into expressionist form.

Toller was only twenty-five but already a national figure when the gates of Niederchonenjeld closed upon him for five long years. He was to leave his cell a mature man with prematurely gray hair. During the time, he had become one of the most popular dramatists of the German theatre, which, given a new lease of life by the revolution, was one of the most progressive experimental theatres in the world. Yet, when he was released, he had never seen a single one of his plays performed.

Massemensch was not Toller’s maiden effort in the theatre. In 1917 he had begun an anti-war play called Transfiguration, which was completed in military prison. The play deals with Toller’s own adolescent life and inner struggle to maturity. Toller was born in Bromberg in 1893. His father, a Jewish merchant, died before he was sixteen. After completing secondary school, the boy went to France to study at Grenoble. That summer the war broke out. Filled with youthful ardor and passionate love of country, Toller hurried home to enlist. There followed thirteen months of military service at the front. The sensitive, high-strung boy was exposed to the horrors of trench warfare. He was wounded in Foret des Pretes, sent home to a sanatorium, where his wounds healed. But his mind was scarred by war. Adjudged a war cripple, he went to study in Munich, then to Heidelberg. There he founded a peace organization, the League of Universal Youth. During the munitions strike in Munich Toller was arrested and was not set at liberty until the revolution broke out in Bavaria. Influenced by Kurt Eisner, journalist and poet, a leader in the radical socialist party, Toller joined the party. Eisner’s assassination, at the hands of the reactionary Count Arco del Valley, deeply affected the young convert and caused him to give up everything and plunge with abandon into the revolutionary struggle. He became one of the leaders of the Independent Socialists.

Transfiguration is written in thirteen staccato scenes, called “stations,” after the stations of the cross. The action takes place in Europe “before the beginning of regeneration.” Its prologue opens in the barracks of the dead with a macabre dialogue between two characters, Death-by-War and Death-by-Peace in which the war is held up to ridicule with grim humour. The play moves swiftly from its opening scene between the hero Friedrich and his mother and his friend to his enthusiastic enlistment for war. There follow scenes on troop trains, at the front, in no man’s land, in a field hospital, back home at peace, working in an artist’s studio. The hero, in the guise of representative characters in presentday life, tests the structure of society in a succession of scenes-a tenement, a prison, a worker’s meeting. Finally, in a symbolic scene crossing an Alpine abyss, he follows his friend into the clouds. The closing scene is in a church. Every institution is revealed as bankrupt in present society and the play ends on the ecstatic note of:

“Brothers stretch out your tortured hands,

With cries of radiant, ringing joy.

Stride freely through our liberated land

With cries of Revolution, Revolution!”

Transfiguration, which was produced in the beginning of 1919 by Die Tribune, an independent theatre of Bedin, is one of the first “conversion” plays written. Its prologue bears a striking analogy to Irwin Shaw’s brilliant anti-war play, Bury the Dead, which made theatrical history on Broadway last season. Both plays employ the same theme and move toward a revolutionary solution; both stop short of a concrete program. Both attack the status quo and the war satirically; both offer no way out. Both represent the attitude of the petit bourgeois intellectual caught between classes in a moment of sharp social conflict.

Transfiguration is actually autobiography in dramatic form. Its passionate ecstatic style is typical of a whole series of ego-dramas (Ich Dramas) of the period-plays in which the author, thinly disguised, stammered his hatred, his inner rebellion against old forms and conventions of pre-war society, attacking the family, the church, the state and all organized institutions. Post-war Germany, defeated in war, balked in carrying out a thoroughgoing revolution, had reached a stage of chaos and disillusionment.

It had become a country of defeat, a nation reduced to neurotic despair and economic paralysis in which the decayed republic offered no impulse toward regeneration or vital social change.

Friedrich, the hero of Toller’s first play, is an extreme type not an individual character; he is Man. The progression of his internal experiences form the only binding link in the play which consists of swiftly shifting scenes and countless characters without any plot. This is the dream technique of Strindberg’s Ghost Sonata transposed into a nightmare vision of society. Transfiguration exhibits at once the lyric strength of expressionist technique and all its weakness.

Expressionism as a style in art, literature, music, and the drama was not specifically a product of the war. Many of its earliest works were written prior to 1914. Frank Wedekind, whose dramas portray the decayed, degenerate, sensual, perverted types of European society in a manner akin to George Grosz’s masterly savage caricature, was a precursor of expressionism. Walter Hasenclever’s drama, The Son, often called the first expressionist play, was written in 1913, but was not produced until after the war, when it became a popular success. Even such extreme forms of expressionism as the painter Kokoschka’s short plays, The Burning Bush and Murder, the Hope of Women, were written between 1907 and 1911. Their apocalyptic style is prophetic of the breakdown of society after the war. Both plays were suppressed in production.

The most recent development of expressionism as an art form has been in Germany, but the style appears always in a period of social change and break-up during the transition from an old form of society to a new one. We have examples of expressionist art from the earliest historic epochs. For instance, the Fayum portraits, funerary paintings executed on wood for the mummy cases in Egypt during the first and second centuries A.D. are expressionist art of great power. Strikingly modern in effect, they mirror the change of consciousness from classic pagan society to the slowly emerging new Christian world. There can be no expressionist art today in Germany, not only because no art at all is possible under fascism but because a definite political party, representing a complete viewpoint is in power. Similarly there can be no expressionist art of any value in the U.S.S.R., because with the triumph of the proletarian revolution, society has undergone a basic change and all conditions are prepared for the development of a great classic art in all fields.

Massemensch has been considered Toller’s masterpiece. Completed in prison in 1921, it was dedicated to the workers:

World Revolution

Mother of New Power and Rhythm

Mother of New Peoples and Patterns

Red Flames and Century in the Blood of Expiation

The Earth Nails Itself to the Cross.

The play, Toller declares, “literally broke out of me and was put on paper in two days and a half…My mind was tortured by visions of faces, daemonic faces, faces tumbling over each other in grotesque somersaults. In the mornings shivering with fever, I sat down to write and did not stop till fingers, clammy and trembling, refused to serve me. No one was allowed in my cell even to clean it. I turned with uncontrollable rage, against my comrade who asked questions or wanted to help me. The laborious and blissful work of pruning and remolding lasted a year.”

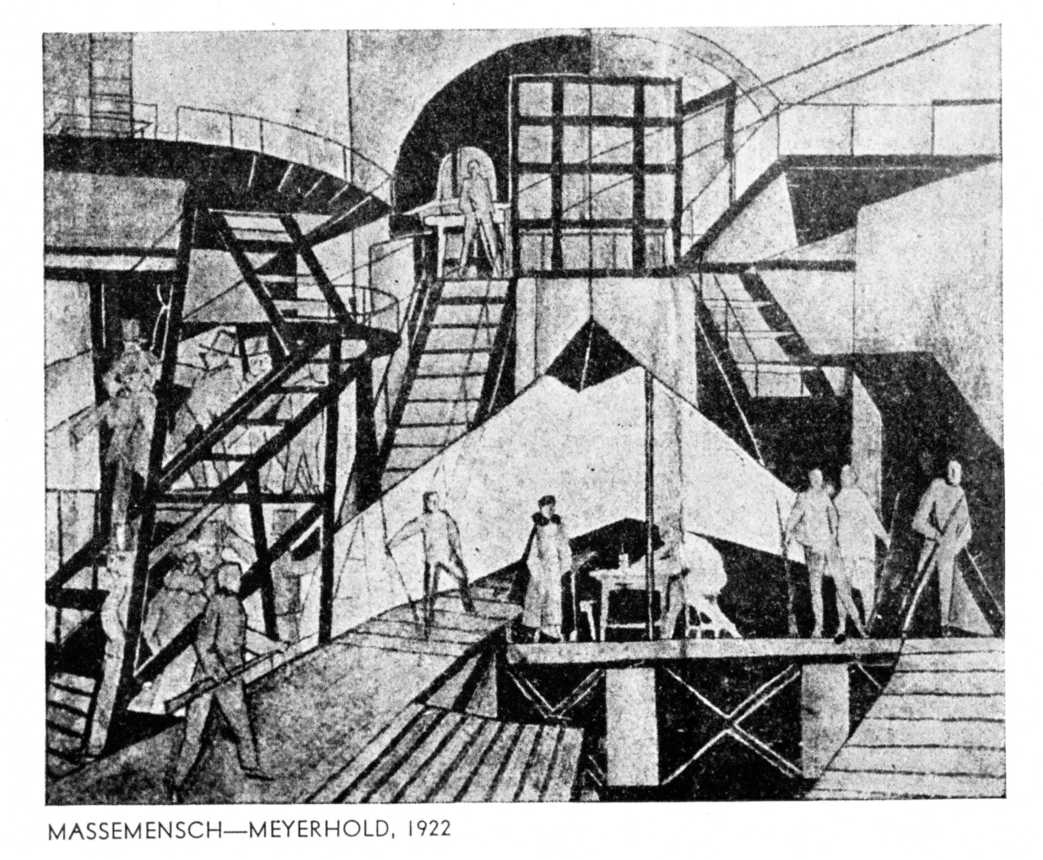

Written in the clipped tumultuous rhythm of free verse, Massemensch kindled in its German audiences something of the troubled sombre ecstasy which Toller experienced in writing it. Nevertheless it remains a dialogue between the intellectual, Sonia, and the spirit of the Masses, the Nameless One, carried on against a background of worker choruses that have something of the lofty tragic note of Greek drama. It lacks, however, the three dimensional complexity and rich texture of reality, due, no doubt, to the fact that “the form was conditioned by the inward constraint of those days” and that “the immensity of the days of revolution had not yet formed an ordered mental picture, it still lived on in me as a kind of torturing spiritual chaos.”

The word duel carried on between Sonia and the Nameless One paraphrases in modern terms the old dualistic struggle of Faust, the searcher for truth, and his subtle Mephisto double, the eternal compromiser with reality. That Toller has so understood it is proven by his comments on the play in his recent book on America and Russia, Quer Durch. It becomes apparent that for all his actual experience in the Bavarian Revolution, Toller had not yet clarified its meaning or understood the role of the proletariat as the leader of social revolution. Sonia, the heroine of Massemensch, a middle class pacifist intellectual, prefers to perish before the firing squad for her part in the revolt rather than escape at the risk of the gaoler’s life. Such an attitude demonstrates that the Bavarian Revolution had not reached a sufficient ripeness for victory. How different, for example, is the conduct of Malraux’s working class hero, in the novel, Days of Wrath. He accepts without question the sacrifice of a comrade’s life in order that he may be free from the Nazi torture prison to carry on his necessary work, a work for which he is willing to risk and even lose his life.

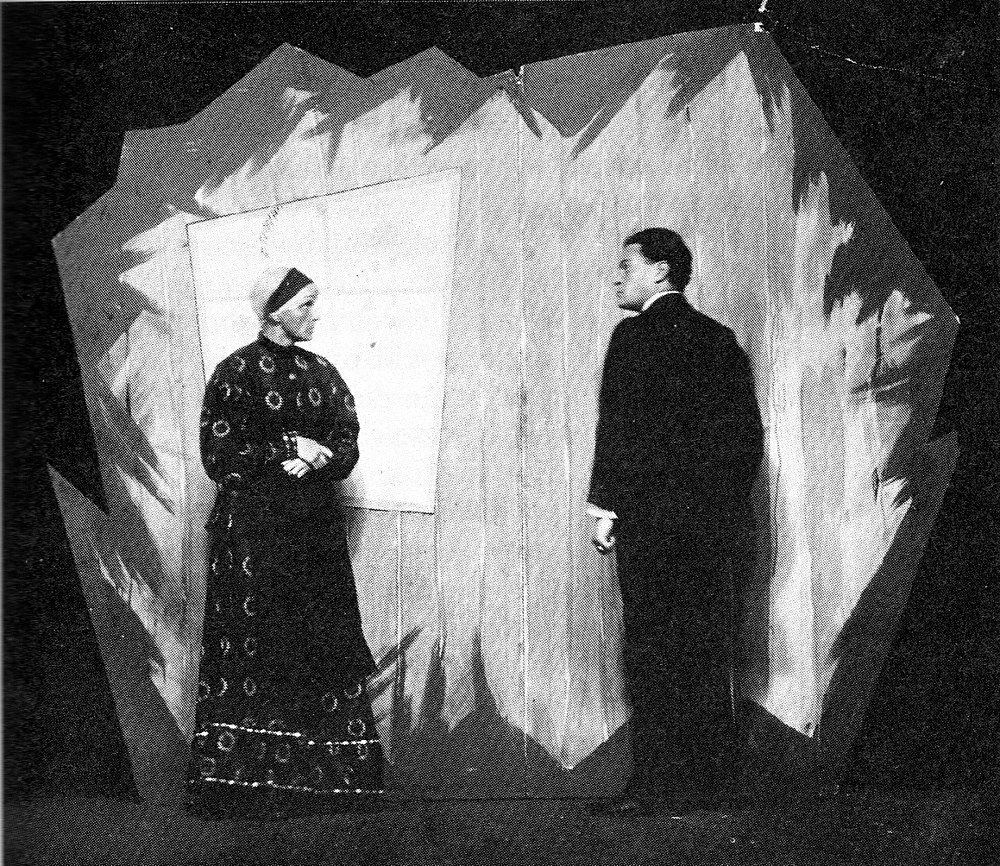

Massemensch was a historic landmark in the German theatre. It succeeded in dramatizing the class struggle, although in dream form, on the stage. Toller’s next play, The Machine Wreckers, was a historical drama of the Luddite Rebellion of the weavers in England in the early nineteenth century. I saw the elaborate presentation of it in Berlin in 1922 at Reinhardt’s Grosseschauspielhaus. The enormous stage with realistic cyclorama of great dimensions was built up with a gigantic weaving machine against which the rebellious workers appeared like pigmies. In effect this dramatized the terror of the machine and the weakness of the workers, giving the play a defeatist feeling. Overloaded with mechanical and spectacular paraphernalia, the action was dwarfed and the production weakened. In itself The Machine Wreckers has not the compact simplicity of Massemensch so beautifully mounted by Jurgen Fehling, who now works in the Volksbuhne for Hitler, the man who savagely destroyed every trace of working class organization.

The Machine Wreckers is set in Nottingham at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in England during the economic distress following the Napoleonic wars. It contains much of Shelleyan romanticism and revolt. In some of the scenes we hear Shakespearean echoes. But the play does not so much dramatize the desperate plight of the weavers, who destroy the machines which rob them of daily bread, as the modern intellectual’s revolt in the post-war period against our machine-made civilization.

The prologue of The Machine Wreckers revives dramatically the historic debate in the House of Lords over the bill which made the destruction of a machine punishable by death. Lord Byron came to the defense of the workers but was outvoted. Based on the actual debate in the House of Lords, Byron’s speech is the intellectual’s plea for mercy, explaining the worker to the ruling class and asking for charitable treatment. The worker is portrayed as “the starved rabble,” the intellectual as the patron saint of the working class. While such an attitude is undoubtedly historically correct, for the period, Toller does not differentiate in the play itself his own viewpoint from that expressed by the character Lord Byron. Such a charitable espousal of the working class cause, recalls the movement of the Russian intelligentsia in the ‘eighties called “going to the people.”

Jimmy Cobbett, the hero of The Machine Wreckers, is depicted as a conciliatory worker-intellectual, vainly trying to solve the class conflict by conciliatory methods. In sharp contrast, John Wibley, the proletarian, is portrayed as a blind force driven by hatred, physically repulsive because he is a cripple with a hump. Such bias voices the author’s misunderstanding and fear of the worker. It is the attitude of the over-sensitive, protected intellectual who has no first-hand knowledge of the workers. Menshivism is echoed in the words of Jimmy Cobbett: “Persuasion serves our ends,” while John Wibley is given the reply: “Blood is the lash to wipe out sloth.” This is an intellectual’s misconception of revolutionary agitation. It is further elaborated in the scene between Jimmy Cobbett and the mysterious Beggar, a sort of Teieras of the class struggle, who counsels Jimmy against the “new Gods” called “holy workmen.”

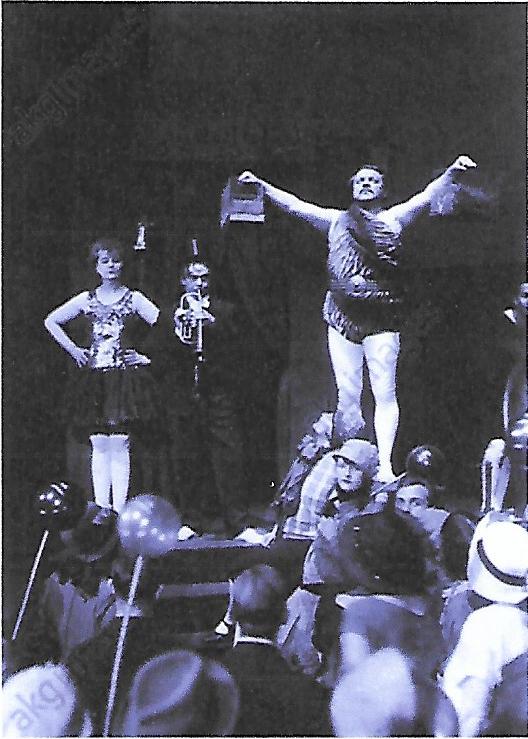

Toiler’s next play, Hinkemann, is a German morality drama; it was completed in Niederschonenfeld in 1922. Despite its treatment of a difficult subject, its well-made form made it much easier to produce. Hinkemann, a symbol of Germany in defeat, is a soldier who has been maimed in the war in the same manner as the hero of The Sun Also Rises. Hinkemann returns home a living dead man, ashamed before his fellow workers, unable to face his beloved wife. Maggie betrays him with his best friend, while the unwitting Hinkemann anxious to provide her with comforts, at least, accepts a job in an amusement park performing as a strong man who bites the throats of live rats and drinks their blood. The gist of the play is contained in the cafe conversation which Hinkemann has with his various friends, each one of them a representative of some political tendency in Germany which claims to be able to rescue the country. There is Singegott, the religionists; Max Knatsch, the liberal and anarchist; Michael Unbeschwert, the communist; Peter Immergleich, the stand-patter; all debate various panaceas for Hinkemann’s sorry condition but find no solution. Hinkemann discovers Maggie’s betrayal and, deeply wounded, feels that his is a living death: “A man who has no strength for dreams left has lost the strength to live.” He begs Maggie to start a new life without him but she throws herself out of the window into the courtyard and is killed. Over her dead body Hinkemann’s last words are: “Any day the Kingdom of Heaven may arise, any night the great flood may come and cover the earth.” Despite many poignant scenes and its passionate upbraiding of war, the play remains inconclusive. In Hinkemann the scenes of bitter pessimism with his wife and in his address to the Priapus statue recall the mood of O’Neill’s All God’s Chillun, when the white wife addresses the African mask and rails against her marriage with a Negro.

Shortly after Toller’s release from prison, in 1925, the Kleine Buhne of Prague produced a new satirical play of his, Wotan Unbound. Wotan, the barber, thinly conceals the identity of Wilhelm II and the play is a savage attack on the old regime which dragged Germany into war.

The plays written subsequent to Toller’s imprisonment lack something of the tumultuous tense manner of the early period. In addition to plays, Toller had written a Requiem for the Murdered Brothers, a mass chorus, and a book of poems, The Swallow Book.

Hinkemann had its premiere in the State Theatre in Dresden in 1924. The reactionary elements of the city deliberately planned a first night riot. Money from a state charity was used to buy 800 tickets which were distributed with printed instructions and cues when to hiss and create disturbance. In the first scene, the director had inadvertently cut the cue for the riot and so it took place only with the second scene but assumed such dimensions that the performance could not be heard. A man sitting in a box was so alarmed that he had a heart attack. The anti-semitism already being fomented in Germany found utterance in the rioters screaming, “Let the dirty Jew die.”

Piscator, the first creator of a social theatre in Germany and its most progressive director, chose as his first play for the new Piscator stage, located in the old Theatre and Nollendorf Platz, Toller’s new drama, Hurrah, We’re Alive. Staged in the most experimental manner, it introduced technical innovations by including radio and movies in the body of the play and thus enlarged its scope immensely. It tells the story of Karl Thomas, a revolutionary, who, having a sentence of death remanded, is kept in a lunatic asylum for seven years. He comes back to society to find it more of a madhouse than his prison. In a quick succession of simultaneous scenes the anarchy and absurdity of the capitalist system is revealed. Into three hours’ performance Piscator succeeded in compressing a decade of contemporary German history. Piscator used the script like a movie scenario, to which it has a close resemblance, and constructed in visible three dimensional scenes behind a transparent screen the social and economic struggle going on in Germany. Such a play in 1927 was indissolubly welded with the audience which witnessed it. Each performance was a vivid symbol of the contemporary struggle being waged compressed into an experience of tremendous import.

Draw the Fires, written in 1931, is the last of Toller’s revolutionary dramas. Dedicated to the memory of the sailors, Kobis and Reichpietsch, who were shot on the 5th of September, 1917, it dramatizes the mutiny of the German sailors at Jutland.

Toller’s work is a confession of faith deeply personalized-a monologue with his own soul in which the other characters are incidental. He is above all a lyric poet and often we hear Shelleyan accents in his verse. His dual interest in poetry and politics is reminiscent of the early romanticism. Toiler’s development has progressed in later years away from youthful lyricism toward a more realistic approach to life. His latest plays, The Blind Goddess, and the collaboration with Hermann Kestner which produced Mary Baker Eddy, are dramas in more conventional form with real character and a developed plot. But technical innovation and a greater solidity do not compensate for the earlier note of ardor and passion. In his very first play, Toller attacks the problem which is closest to him. In his later plays he moves away from it.

Transfiguration deals with the problem so acute for the adolescent of trying to find a place in the world. This struggle is always enhanced in the case of the intellectual. Toller, who is a Jew, conceives it in racial terms but actually it is the problem of every intellectual who feels he does not belong until he has won for himself a spiritual dwelling and earned his spiritual bread by the sweat of his brow in the labor for ideas. Friedrich is willing to suffer, even to die, to win his right to his fatherland. His most tragic moment is not physical wounds or sights of death around him, but the moment when his comrade reminds him that he is a stranger and that even a hero’s deed in no man’s land has not won him citizenship in his fatherland. Friedrich, in the end, smashes the statue of the fatherland and finds a new one in the revolution. But again the same conflict reappears in the later plays, Massemensch and Der Deutsch Hinkemann. They register the effort to cross over from one class to another.

Despite his participation in the Bavarian Revolution, Toller has not yet won a place in the fatherland of the working class toward which his heart and mind has drawn him. Between him and the working class, barriers still remain. Despite his experience in revolutionary action and in prison, he has not gained sufficient insight. Inadvertently he continues to misunderstand the worker and to reiterate certain old prejudices imbibed in childhood from the ruling class. He has not crossed the divide between classes; he remains the poet of no man’s land in the class battle. In his early plays, there oscillates the conflicting rhythms of pacifist humanitarianism and the call to revolution; a delicate repulsion for the crude realities of existence alternating with wanton cruelty in which sex and sadism mingle. Here the revolution is conceived either as a miracle which will bring a golden age or as a blind and destructive force.

Something of the old Peasant War of the sixteenth century lingers in the lines of The Machine Wreckers. There is more of the apocalyptic vision of the Anabaptists than of the Luddite Rebellion in the play, its religious fervor in Transfiguration, Massemensch and Hinkemann. The Bavarian Revolution itself with its anarchist, intellectual-Bohemian leadership has something of the Peasant Revolt of Thomas Munzer- something that looked backward as well as forward. This, perhaps, explains its early defeat. Too much of agrarian tradition, too little of industrial discipline in the rank and file in Bavaria, a country of rich peasants, too much of Bohemianism and anarchism in the leadership without the shrewd grasp of reality or controlled responsibility. Pushed to cooperate, the Communists saw the inevitable defeat, but struggled to make it an honorable and courageous one; they knew the pessimism and passivism would lead the masses to death and defeat, foresaw that the balance of forces was not ripe for victory. When the Bavarian Revolution went down to defeat, it opened the way to Hitler and his beer hall putsch.

History, an American poet has said, is not literature; acts cannot be erased like words. Each act carries its inevitable con sequences far into the unseen future. Hence it is that the intellectual over-sensitized to the task of creating cultural values-a heroic program of another pattern-is often unsuited to the role of politician or statesman. Not that the man of thought is necessarily more passive, but his activity fulfills itself in a different sphere. The activity of the revolutionary intellectual sculpturing the new morality is as intense and vital and difficult as the activity of the revolutionary leader shaping the destiny of a people on a political and economic basis. Both are necessary tasks and both demand heroism of a different calibre and quality. But when the intellectual, his emotions and experience undisciplined by reality, undertakes a revolutionary task in the external world, he must become another man.

For the petit bourgeois intellectual of the period, it was no easy thing to espouse the revolution. Toller underwent a deep spiritual struggle before he could accept and join the revolutionary movement. He was never afraid in his art to depict that struggle and his uncompromising sincerity makes him a pioneer in the revolutionary theatre, a true poet who broke old moulds in order to seek a new form and to make a passionate confession of faith in the new world.

German Protestant as much as Jew, Toller’s problem lies rooted in the idea of faith and the freedom of the individual to make his own judgment. Sometimes faith fails Toller and he reverts to the idea of a vengeful, blind fate as in The Blind Goddess. He is smitten by anxiety about the future and the unknown and overwhelmed by the odds against the new order. He is not sufficiently integrated in the new to know the strength of the proletariat and its historic mission, which cannot fail despite the defeat of the German revolution, and which will find its way to power elsewhere and move to victory for all mankind.

Toiler’s last play, Mary Baker Eddy, written in collaboration with Hermann Kestner and performed at the Gate One Theatre in London in 1934, is a well-made historical play which poises the question of faith as its central motif. In choosing Christian Science as a theme, he is dealing with the power of faith to heal and to work miracles. But he does not succeed in solving it, rather he seems to deny that faith is more than charlatanism and a strong will to power. We observe the unscrupulous and sensual Mary Baker Eddy born to victory by an indominable will and a desire for worldly success, cloaking her real motives in a mantel of pious prophecy the better to gain her own ends. But this religious charlatanism masked as religious faith is one kind of faith only. It belongs to the decadence of Christianity.

But there is a kind of faith possible today which moves in line with the actual progression of events. It is no longer Christianity but the socialist revolution which scientifically attempts to change the old order in line with the discoveries and knowledge of the laws of history. Such a faith is constructive, progressive, and the acquisition of this knowledge is the task of every intellectual in the world today, for only by absorbing and digesting its laws, by integrating its theories with practical daily life and in the work of every individual in each field of activity will that change take place which lies uppermost in the mind of every progressive individual today.

Since his early impetuous and romantic espousal of the revolutionary cause, Toller has moved steadily toward a more realistic attitude both in his work and his revolutionary activities. With America standing on the threshold of the struggle which has wracked Germany for a decade, his example as a writer and as an intellectual leader, should have a stimulating effect on the left-ward moving intelligentsia in the United States today.

The New Theater continued Workers Theater. Workers Theater began in New York City in 1931 as the publication of The Workers Laboratory Theater collective, an agitprop group associated with Workers International Relief, becoming the League of Workers Theaters, section of the International Union of Revolutionary Theater of the Comintern. The rough production values of the first years were replaced by a color magazine as it became primarily associated with the New Theater. It contains a wealth of left cultural history and ideas. Published roughly monthly were Workers Theater from April 1931-July/Aug 1933, New Theater from Sept/Oct 1933-November 1937, New Theater and Film from April and March of 1937, (only two issues).

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workers-theatre/v3n08-aug-1936-New-Theatre.pdf