Anyone interested in art and revolution will find this substantial article, based on Russian documents and decrees, by Masses and Liberator literary editor Floyd Dell, and his fellow-traveler’s eye view, of immense value.

‘Art Under the Bolsheviks’ by Floyd Dell from The Liberator. Vol. 2 No. 6. June, 1919.

From Documentary Reports, Decrees and Plans of the Soviet State

“WHAT is the position of art and artists in Bolshevik Russia?”

The American newspaper reader is not supposed to care about such things—otherwise he would have been elaborately misinformed long since. He is supposed to be more interested in the fate of Grand Dukes than in the fate of musicians and painters and novelists; which accounts for the fact that we have not been regaled with stories of the Five Great Artists Slain in a Well by the Bolsheviks. No, we are not supposed to mind what happens to Beauty and its lovers anywhere; and so it has not been necessary for Mr. Sisson to discover documents proving that secret agreements existed between Lenin and the leader of the Kaiser’s orchestra to the effect that Wagnerian opera should supplant Serge Diaghileff’s Ballet; nor has Mr. Simmons thought it proper to reveal to the Senatorial Investigating Committee that the Anarchists of Vladimir and Saratoff had passed a decree declaring that anybody caught whistling a tune or drawing a picture should be shot against the nearest wall. Nor have renegade socialists like Spargo, Walling, Bohn and Russell been called upon to verify these sinister rumors out of their own inside knowledge of the Socialist movement…But there are people in America who are interested in art and accordingly a little of the poison-gas of American journalism has been allowed to drift in their direction, through the proper mediums of publicity. In artistic circles one may hear of “poor Z– the composer, starving to death— yes, of course—the Bolsheviki care nothing about art! Poor fellow, so gifted—what a pity!” Z– meanwhile is having the time of his young life; he is a member of the local Art Collegium, associated with the most eminent and earnest painters, sculptors, and architects of his town, free for the first time to take their work seriously and as a matter of public importance; he is the head of a sub-section which is organizing huge concerts for enthusiastic working-class audiences; and he has the chance for which he has always pined, of writing just exactly the kind of music he likes, and giving it straight to the music-loving masses of Russia. And any American composer or director who is worth his salt would jump at the chance to stand in his boots, even if he had to live on a low-protein diet and wear his last year’s shirt in the bargain!

An example of the sort of silly tattle spread by counter-revolutionary emigrés and solemnly recorded in the more- or-less artistic magazines of this country is an article by William Trevor Hull which appeared in Vanity Fair last June. It describes the alleged looting of a famous Russian art gallery by the Bolsheviks—the paintings of course being sold “to the Germans.” “Outside the ruthless and unnecessary destruction of French cathedrals by the Germans, in the present war,” says Mr. Hull, “no such piece of cynical vandalism has been perpetrated anywhere in over a hundred years. It is the supreme example of the systematic looting of the country carried out under the direction of the so-called authorities of the present so-called Russian government.”

Outside the utter violation of every tradition of intellectual honor by the governmental experts who pronounced the Sisson forgeries authentic, no such piece of cynical slander has been perpetrated in the history of anti-Bolshevist agitation. It is the most wanton example of the systematic lying about Russia now in progress. That lies about this idealistic government should be spread in the name of Christianity is bad enough, but in the name of art— somehow it seems worse.

Botticelli and the Bolsheviks

At the very time when this picture of Bolshevik indifference to art was being given to America, the administrators of the Bolshevik State were actually concerned, to a degree that would seem incredible to an American politician, over the fate of a Botticelli…Probably Senator Knute Nelson does not know whether Botticelli is a wine or a cheese—and cares less. But Bolshevik Russia does care. May-June, 1918, was a crowded and tragic time in the history of the Soviet Republic; the Germans were advancing—Petrograd might be lost—the Revolution was in its hour of fieriest trial: but when it was reported to the Collegium for the Protection of Art that this painting, “belonging to the citizen Mrs. E.P. Meshersky,” was about to be shipped abroad, the matter was deemed of so much importance that it was at once brought before the Soviet of People’s Commissaries in Moscow, which on May 30 passed a special decree requisitioning this painting and declaring it the property of the Russian people. A “flying detachment” was dispatched to capture the painting, which was then placed on exhibition! The citizen Mrs. E.P. Meshersky probably did not like this high-handed procedure; she probably called the Bolsheviks thieves; but Russia has that Botticelli safe and sound!

At about the same time the Soviet appropriated 250,000 rubles to be spent in purchasing historically important objects of art which were being thrown on the market by emigrés, and which were in danger of being irretrievably lost by being smuggled abroad; and organized the “flying detachments” mentioned above, to be sent ‘on hurry calls through the provinces to intercept “disappearing” art. These facts appear in the “Report of the Activities of the Section Devoted to the Care of Museums and the Preservation of Objects of Art and Relics of the Past, People’s Commissariat of Education, for the period of May 28—June 28, 1918.”

Preserving the Past—for the Future Museums!

Relics of the Past! Are the Bolsheviks interested in preserving the relics of the past?

They are. You will notice that the Section Devoted to Museums, etc., is a part of the Commissariat of Education. In the report of Lunacharsky, commissar of education, printed in these pages last month, you will have observed that libraries, theaters, potteries and moving-pictures are all part of the Bolshevik plan of education. Education in Bolshevik Russia comprises everything that educates. And museums are accordingly an important part of the Bolshevik educational system—particularly in the department of art. The aim is, of course, to “democratize and popularize” the museums—to make attendance easier, and to facilitate the study of the museums’ contents by lectures and lecture cycles; in addition to which, “excursions and tours within reach of the masses,” and “the widest distribution of carefully executed reproductions of works of art,” were being planned.’ These are forward-looking activities which (the doubting observer might say) are within the imaginative scope of a group of enterprising politicians who are not interested in art but who want to make a showing; but as earnest of the /enthusiastic commonalty of Russian art lovers and the Bolshevik State, is the report of investigations “of an artistic and scientific character” in regard to “ancient fresco works and iconography”! For in that month of anxiety, the Soviet found time to send art committees to various cathedrals to find what neglected treasures might be concealed by dirt and kalsomine. “At the Blagovyeschenck Cathedral of the Kreml, following the washing and cleaning of mural paintings, several ancient frescoes have been discovered…At the Archangel’s Kreml Cathedral, several ancient ikons have been singled out for complete restoration; the work is in charge of prominent and experienced iconographers…It has been decided to undertake a scientific expedition for the purpose of examining the Burilinsk Museum at Ivanov-Voznesensk…”

In the light of these facts, it is not surprising that the museum experts of Russia are busy creating a “science of museums,” that they are planning to publish a “special magazine” devoted to their work, that they are organizing “regular congresses of museum-workers” and establishing “exemplary exhibitions demonstrating the process and development of museum activities.” The report deals at length with the rearrangement and proper cataloguing of museum contents, the training of purchasing agents, the establishment of provincial museums, and puts forth as a matter of immediate importance the founding of new institutions “in those fields of art hitherto quite neglected in Russia, for instance a museum of Oriental art, a museum of sculpture, and a museum of the newest art.”

Here is the report of these alleged art-haters, on the Kremlin gallery:

“The picture gallery at the former Kremlin…has been little accessible. The hanging arrangements do not meet the most elementary museum requirements. Without any system, the paintings have been permanently set into the walls and are separated from each other by only a narrow framework, making an intelligent examination of the Gallery impossible. Moreover, many pictures, owing to differences in atmospheric pressure, have suffered considerably: they show cracks and in many places the paint has deteriorated—all this threatening ruin to the pictures. The system of cataloguing was arbitrary, paintings of the Dutch school being attributed to Italian masters, and first-class works left unclassified while second-rate things were ascribed to first-class masters.

“The Collegium has decided to remove from the Palace’s Gallery paintings interesting from the point of view of scientific examination, and transfer them to the gallery of the Rumiantzev Museum where, after restoration and investigation they might be exhibited for popular examination. Among these are a few pictures of the Rembrandt School, two Netherland primitives, one Florentine portrait of: the 16th century, a sketch by Rubens, and a number of paintings by Italian masters of the 17th century…”

What of Living Art and Artists?

So much for the relics of the past! Such facts as these together with the nationalizing and protecting and subsidizing of all important collections (including the famous Tretiakov gallery in Moscow), sufficiently establish the reverence of the Bolshevik State for the art-treasures which have been handed down from the generations before. But more important than this is the question of what it is doing for the art and artists of the present. What can a State do for artists? The Bolshevik State has done one thing that no other State has ever thought of doing. It has given them a chance to do something for themselves. It has not “patronized” them—it has not thought up silly bureaucratic schemes for making geniuses by state-pensions—but it has turned over the artistic destinies of Russia to her artists. For when we have spoken above of the activities of the Bolshevik State in regard to art, we have been describing the activities of the artists of Russia as a regular part of the Bolshevik State. In Russia the lawyers do not legislate for the artists; the artists legislate for themselves, upon the understanding that they are not legislating for themselves alone, but for the Russian people, in whose education art is an important thing. The artists, to become a part of the Bolshevik State, have only to join the artists’ union, which sends delegates to the Soviet, and to the Collegium which has matters of art especially in its charge; the Collegium makes plans which are co-ordinated with the plans of the other departments of the People’s Commissariat, and enacted into the necessary legislation by the Soviet…It is a government by experts, the only check being that the decisions of the experts must be in conformity with the revolutionary will of the democratic masses, as expressed in the Soviet.

What, then, have the artists of Russia seen fit to do in behalf of living Russian art and artists?

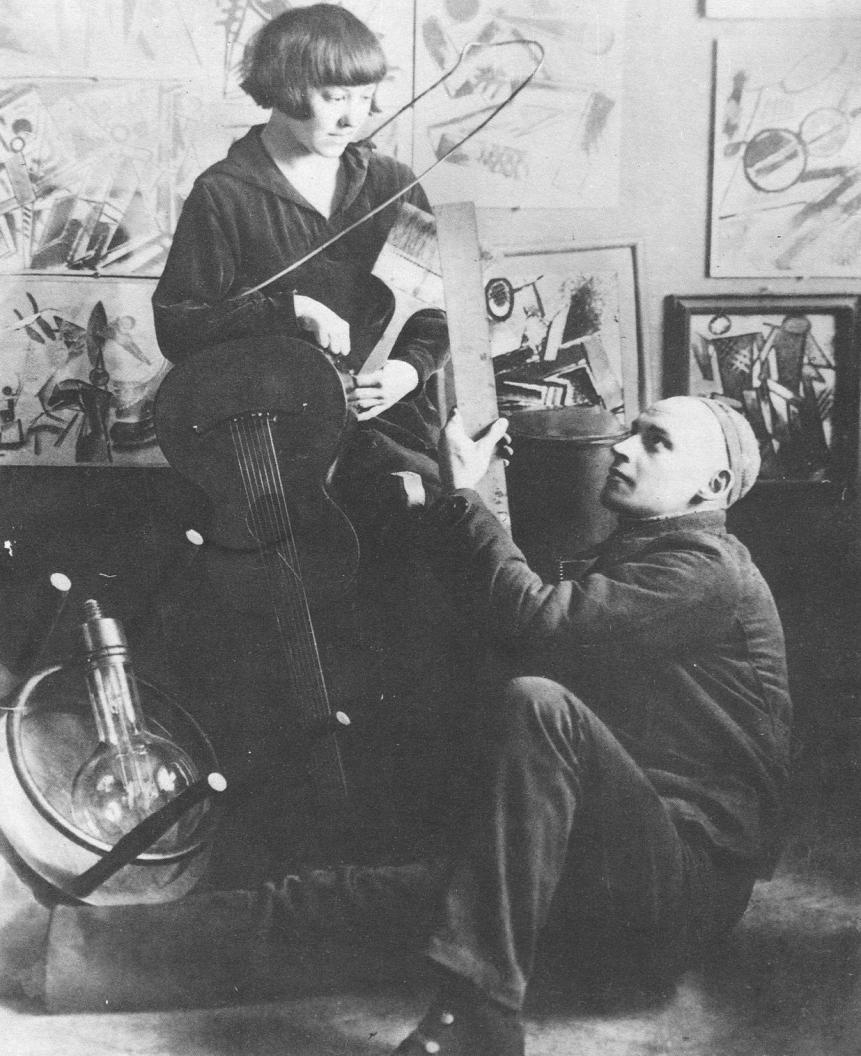

Russia’s Art Program

We have here the report of the Moscow Art Collegium, at least one of whose membership of painters, sculptors, architects and educators our readers will recognize by name—Konchalovsky, Konekoy, Mashkov, Tatlin, Ivanov, Morgunov, Madame Tolstoy, Udaltzeva, Schusev, Noakovsky, Theltovsky, Vesnin, and the Commissar of Art, Malinovsky. These are all distinguished artists and persons interested in artistic culture irrespective of politics. So far as is known, Malinovsky, the Commissar of Art, is the only one of them who is a member of the Bolshevik party. All joined the Collegium as representatives of artists’ unions and art organizations. The Collegium laid out for itself the following program:

“1. To organize state art education: by (a) the establishment of art studios meeting the requirements of the new Russia; and (b) propaganda of art among the large democratic masses.

“2. To effect contact with the world’s artistic centers. To promote the growth of art: by (a) organization of state competitive examinations; (a) organization of artists’ trade unions, mutual aid societies, etc.; and (c) organization of decorative artists’ committees and scenic art workers.

“4. To organize the preservation of the arts of the past and present and plan for the protection of art in the future.”

Destruction and Construction

In accordance with this program, one of the first things they effected—an act which will meet with the sympathy of every revolutionary artist and art-lover in America— was the formal dissolution of two reactionary art institutions which stood blocking the path of artistic progress in Russia—the Academy of Art and the Moscow Art Society; all the funds and properties of these institutions were turned over to the Commissariat of Education, which used them to create an Independent Art School and to further the task of democratic art education. The decree discontinuing the Moscow Art Society is dated July 12, 1918.— “There is,” as the translator of this decree notes, quoting Strindberg, “so much that only needs to be destroyed!”

On July 18, the Moscow Soviet, after hearing the report of Prof. Bokrovsky, authorized the Commissariat of Education to prepare a list of great men, “worthy of being honored with memorial statues by Soviet Russia.” The list as finally decided upon included thirty-one revolutionists and social workers (including, along with Spartacus, Danton, Marx, etc., the name of Plekhanov, up to his death a fiery opponent of the Bolshevik party!); ten novelists and poets, including Tolstoi and Dostoevsky; three philosophers and scientists; five artists; three composers (Musorgsky, Skriabin, Chopin), and two actors.

But, more significant than such a list, is the set of terms of competition, as drawn up by the Art Collegium and approved by the Soviet. We quote from the Collegium’s report:

“The difficulty consists in preventing the necessity for speed in the execution of the plan from interfering with the artistic excellence of the work; for the State, no matter in what condition it is at present, cannot and must not be the imitator of bad taste.

“For this reason the Collegium has adopted entirely new principles, which up till now have never been tried, either in our own country, or, so far as is known, anywhere else in the world.”

In Behalf of Young Artists

“It has been determined, on the one hand, to open the competition as widely as possible and thus attract the youngest and newest forces among the sculptors; and on the other hand, to interest the great masses of the people and make them participate so far as possible’ in this work of artistic creation.

“Formerly, under the bureaucratic regime, such competitions were restricted to famous artists, or to such as were economically secure and could afford, without thought of the loss of time, to participate. The results of those competitions are sufficiently known: their works are now being cleared off the city squares. All the young artists, quartered in garrets and dark rooms, without any civic rights, were forgotten and shelved. Everything new in art was persecuted. We are all familiar with instances of this treatment. Such was the condition of the artist, and especially of the beginner.

“There is only one way out: to attract young and fresh forces in art, those artists who heretofore have been denied the opportunity of doing public work—and to give them an opportunity of expressing themselves freely in a free republic.

State Support for Artists

“Therefore, abolishing all kinds of restrictions, the Collegium considers it advisable to give the sculptor his opportunity for free expression, by securing him economically during the time of his work.

“The Collegium also considers it necessary, in determining the awards of the competition, to abolish the customary jury, and establish a jury of the people themselves for the judgment of all the projected works, at some place especially designated for that purpose.”

The terms as announced to the Moscow Professional Union of Artists-Sculptors, are specific; any member of the union may compete, and will be paid for his three months’ work, “including expenses of material, casting and placing of the cast.” The subsidy, “amounting to 7,910 rubles for each monument,” will be paid in two sums—4,000 rubles at the time of commencing work, the rest six weeks later. Anyone receiving funds and not completing his work, without satisfactory excuse, will return the money, and the union holds itself responsible for his doing so. Anyone not a member of the union may also compete, but he will not be paid for his work unless it is considered worthy of attention.

“These monuments,” to quote again from the Collegium’s report, “will be erected on the boulevards and in the squares, etc., with citations carved on the pedestals or on the statues themselves, and these monuments shall serve as street platforms from which shall flow into the masses of the people fresh thoughts to inspire the mind… t is believed that the execution of this plan will introduce a great stimulus into our dead artistic reality, and throw a spark into the artistic consciousness of the people.”

Art for the People

What is especially noteworthy here, aside from the plan for encouraging young artists to come before the public, is the mingling of revolutionary and artistic enthusiasm—as if they were indeed one and the same thing. We in America, in the midst of our own “dead artistic reality,” are so much under the spell of the “art for art’s sake” philosophy that it may be hard for us to understand this. It may be difficult for American artists, disgusted as they are with the results of academic jury methods, to have any confidence in “a jury, of the people themselves.” But it’ is necessary to understand that in the fiery crucible of revolution the hopes of art have become one with the hopes of mankind. This is the finest thing about the program of the Russian artists under the Bolshevik state: they do not despair of the people, they do not despise nor turn from the people. A new beginning has been made, and the people, while acquiring all the knowledge of art history and technique that enlightened educational methods can give them, and gathering strength and confidence for participation themselves in the joyous labors of art, are meantime to be the judges of whether art is doing what art must do to be alive—expressing their will, their love, their pity, their hopes and fears, their enthusiasms and their dreams.

Tolstoi was right after all: art must be of and for and by the people! And in Tolstoi’s own land his revolutionary aesthetic philosophy, which unites in fecund marriage the too much separated forces of beauty and of truth, is being made the basis of artistic culture.

That this is true is shown most clearly of all in a document dealing with the “Main Problems of the Art Sections of the Soviet of Workers’ Deputies.” Each Soviet has its Section Devoted to the People’s Education, and to the latter is usually attached an Art Sub-section. For the guidance of these art sub-sections, a report was drawn up in which their principal problems are outlined. These problems are stated to be four:

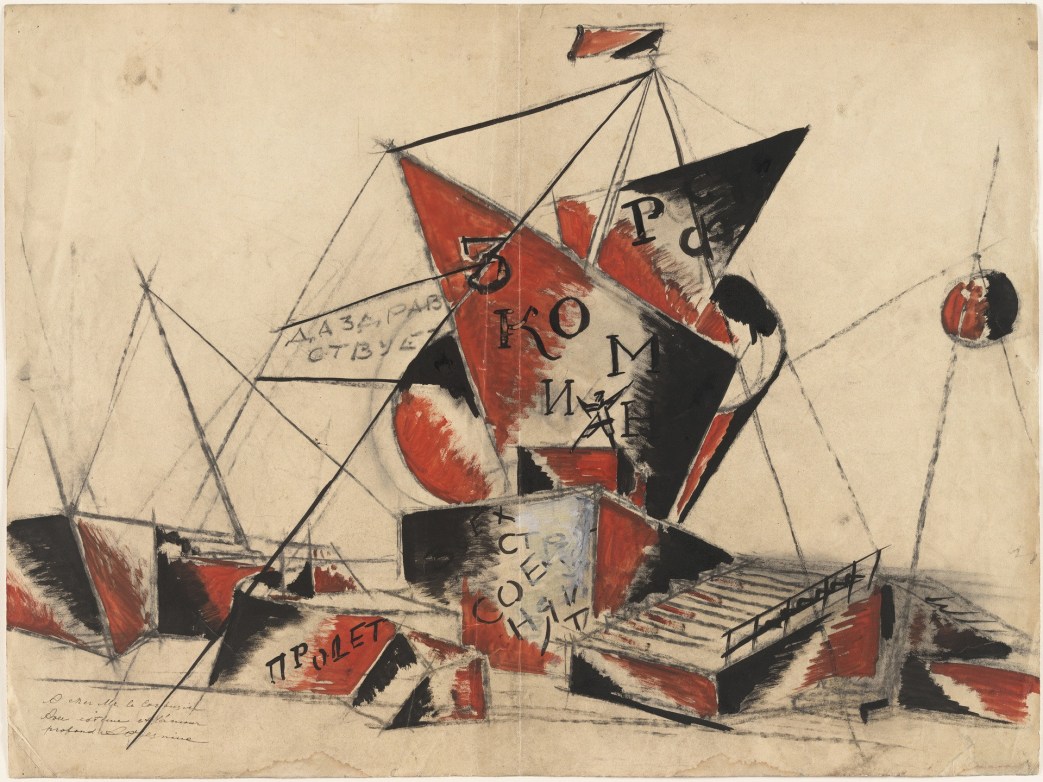

“First, the socialization of art. There are two steps by which. this can be best and most easily accomplished. The preliminary step consists in the external beautification of cities, chiefly of course large cities—turning them not only into village-cities, park-cities, garden-cities, but into museum-cities—museums of magnificent buildings, beautiful monuments—in a word—make them resemble that picturesque London of the future described by William Morris in his utopian ‘News From Nowhere’…Something has already been done in that direction; suffice it to mention here the erection of fifty statues in Moscow in honor of leaders and heroes of the world revolution, the erection in Mars Field of memorial monuments to the victims of the Revolution, the decision of the Penza Soviet to erect a monument for Marx, etc…

Art as a Communal Emotion

“The other step in the socialization of art—turning it into a communal emotion—is the holding of solemn and sumptuous national and revolutionary Socialist holidays: — similar to those which were so frequently and gorgeously celebrated during the days of the great French Revolution, when famous artists, such as David, and prominent composers, had charge of these feasts and beautified them with their compositions. At these revolutionary and Socialist festivals, art, music, songs, decoration, ought to play an important role. And the ceremonial pageant, already a thing of beauty, ought from time to time, at large squares, and especially, in summer, beyond the confines of the city, to arise to the dignity of a real festival of art.

“The second problem to be solved by the art sections will, consist not only in evoking in the large masses of the city populations an interest in all things artistic, not only in the democratization of artistic appreciation, but also in laying the foundations of a genuine proletarian socialist art.

“The best means for solving this second problem include the staging of such plays as represent bourgeois society from a critical point of view, satirizing its manners, heroes, favorites and ideals; or such as invest with tragic dignity the struggle of the workers against their oppressors, or celebrate the revolutionary effort of the working-class for emancipation, and finally such as concern themselves with the birth of a new socialist culture and morality.

“The accomplishment of this aim, the planting of the seeds of a proletarian Socialist art, can be considerably aided through the organization at People’s Houses and Workers’ Clubs, and on some solemn occasions at theaters, of specially arranged literary and musical evenings—devoted from beginning to end to this particular theme of the occasion, for instance the Idea of the Revolution, the significance of May First, proletarian poetry, etc. But it is necessary not only to socialize and democratize art, it is also a matter of the utmost urgency—and this constitutes the third problem of the art sections—to prepare the masses of the urban population for the comprehension of aesthetic values, to give them an artistic education. It is clear that the following measures should be undertaken to accomplish this:

“(a) The publication of small handbooks, inexpensive but well printed, on the history of Russian and West European art, in order to give the workers a familiarity with and an understanding of the works of the great masters of painting and sculpture;

“(b) The publication at popular prices of reproductions of representative specimens of Russian and European art, especially of works dealing with social themes—the toiling life of peasants and workers;

“(c) The arranging of lectures on art, which in a popular way, and with the aid of moving-pictures, will acquaint the toilers with the evolution of art styles, the influence of social conditions on art, and the technical aspects of the art of different epochs; and—

“(d) The building by the art sections of special art libraries and reading-rooms.

The Masses as Creators of Beauty

“The fourth and last and perhaps the most essential and important problem is to make the proletariat capable not only of comprehending and criticizing things beautiful, whether in the form of stage representations or the creations of brush or chisel, but also capable of themselves creating those beautiful things: first, in forms inherited from the past, and then in new forms corresponding to the psychology of these new classes. The establishment of schools of drawing, modeling, acting and stage-decoration, and the creation of People’s Art Academies, with lecture-halls and studios, should be used in the task of transforming the toilers from passive observers and critics of beauty into creating artist-— builders of a new proletarian Socialist art which we believe will surpass in its grandeur the art of the past.

“With these aims in view, committees should be formed for the beautifying of cities, the organization of national holidays and pageants, the giving of revolutionary Socialist concerts and performances, and the founding of lecture courses, libraries and schools—committees representing the soviets, labor organizations, artists, actors, stage directors and specialists in the history of art.

“Our duty lies in making art a communal joy, not only in making the great masses of the urban population interested in art, but particularly in strengthening and promoting the artistic aspirations of the revolutionary proletariat—giving then so far as possible a thorough art education, but crowning the work by training them for active artistic creation. To prepare the ground for a new art created by a new people—such is the aim of the art sections of the Commissariat of the People’s Education.”

These are magnificent aims; the record of work actually accomplished under the conditions confronting these enthusiasts can scarcely be expected to be as exciting as these plans. Yet, besides patience and the tenacious holding on to these purposes in spite of discouragements, there is matter to enhearten us by its sturdy realism in the report of the Art Educational Section of the Moscow Soviet.

Art Education: The Theatre

It deals with efforts in the more direct and emotional and democratic arts of music and the-theater. The report begins with the confession that ‘‘much “time”—all too much time! —has been occupied with “administrative activities,” to the loss of the art-educational side of the program; and some of these administrative activities have a quaint enough flavor to our minds. For instance, it was necessary, besides the ordinary work of managing the State Theaters and Dramatic School, and participating in the management of People’s Houses and the Soviet Theater, and the general supervision of Moscow theatrical activities, to solve any number of ticklish problems in regard to the “requisitioning of premises occupied by theaters and by members of the theatrical and musical professions, and the issuance of permits for the removal of valuables contained in safes.” ‘That is to say, as a member of the bourgeoisie, Mr. X. may be considered to be occupying too many rooms; as an artist or musician, however, he is properly entitled to extra studio-space. And so with the contents of certain safes; as private property their status is different from what it is as a part of the appurtenances of stagecraft, which is now an affair of the people. One gathers from the report that the tact of the art-section resulted finally in the enthusiastic adherence of actors and musicians to the program of the Soviet; but everyone knows how difficult actors and artists are to handle! The report passes with manifest relief from a sketchy account of these troubles to its work in. art-education.

“The October Revolution,” it remarks, “temporarily frightened away many individuals in the theatrical profession from Soviet activities; but they have gradually come back. A number of conferences with the Actors’ Trade Union resulted in an agreement as a result of which the Moscow theaters (the Little Theater, the Art Theater and its studios, the Komissarjevski, the ‘Bat,’ etc.), hold performances in co-operation with the art-section. During the summer season, the section staged many performances, aided by the cast of the Komissarjevski Theatre, the House of Free Art, the ‘Bat,’ and Voljanin’s Players.

Music

“Simultaneously, the organization of district concerts was in progress. The section organized over two hundred such concerts in Moscow and vicinity. A Soviet of Music was organized, with the object of introducing greater system as well as to effect democratic control of Moscow musical activities. Meetings of the Music Soviet were attended by all the prominent leaders of the musical world. As a result of its discussions, a bureau was elected, comprising the chief musical personages, to outline a plan of Soviet musical work. It was decided to organize a music committee of thirty persons, fifteen representing the musical world, and fifteen from labor bodies, including two representatives of the students in music schools”—which now, presumably has the musical activities of Moscow in its charge.

The People’s Theatre

The theatrical activities of the section met an instant and wide response. “Constant requests from various localities in regard to the character of plays to be staged at the People’s Houses, as to what plays are on hand and how they may be obtained, has brought into existence the Repertoire Committee of the section. This committee has worked out a list of plays suitable for performance, has read others, and is preparing a more detailed list of carefully selected plays. The following principles”—and here again we find the characteristic Russian unity of artistic and revolutionary enthusiasm—” have been accepted by the Committee as the basis of the repertoire:

“1. The list can include only plays the artistic value of which is beyond reproach.

“2. These plays, by the impression they create on the audience, must coincide with the spirit of the times—that is, they must evoke a vigorous disposition intensifying the revolutionary fervor of the masses.

“The Committee is preparing for publication a book which will include, in addition to a list of plays, a brief summary of them, and stage directors’ notes regarding their production. This book ought to aid local players in the selection of plays, as well as in the improvement of staging, The Committee is also preparing for publication a number of out-of-print plays, and a collection of articles on the history and theory of the theater; also books dealing with practical questions in regard to the technique of the theater.

“We are also issuing our own magazine, the Izvestia of the Art Educational Section. Judging by the demands for the magazine from the provinces, the need of such a publication is tremendous…”

The report goes on to outline this section’s specific plans for the summer season, which include the staging of Verhaeren’s “Dawn,” the organization of district theatrical performances, symphonic orchestras, chamber concerts, outdoor concerts, children’s theaters, pageants, etc., “not only to offer to the people sensible and artistic recreation, but also to involve the masses themselves in active artistic creativity.”

We now come to the report of the Repertoire Committee mentioned above, which specifies more in detail the principles which underlie the selection of plays, as follows:

“1. Plays on the repertoire. list must be artistic, and adapted to stage presentation. 2. They should heighten and strengthen the revolutionary spirit of the masses. 3. They should be optimistic in spirit.” If there is a shock for the sympathetic American rebel in that last specification, it should be remembered that “optimistic” means something different in Russia from what it means to the pursy backers of our theatrical enterprises; the word should probably be translated as “spiritually strengthening” for it is certainly not intended to exclude tragedy. The preliminary list of dramatists contains the names of Gogol, Tolstoy, Turgeniev, Tchekhov, Gorky (whose “Night Asylum” is hardly optimistic in the vulgar bourgeois sense of that word!), Calderon, Lope de Vega, Cervantes, Shakespeare, Beaumarchais, Moliere, Schiller, Ibsen, Shaw, Romain Rolland, Verhaeren and Hauptmann, besides others not known to the American public.

The Theatrical Section’s report describes its plan of “establishing a whole network of theatrical schools.” These schools, according to later information, are already functioning throughout Soviet Russia. They are divided into two grades; in the lower grade is taught the technique of dramatic art—diction and plastic gesture; in the secondary grade, the pupils receive individual instruction at the studios of the teachers. The object is to develop the individual capacities of each student. General science, with lectures and laboratory work, is also a part of the teaching at these schools. No fees are charged.

A Theatrical Academy

A Theatrical Academy in which the theory of theatrical and dramatic art will be taught, is to stand at the head of this chain of schools, In the lower schools, the training not only includes acting, but stage managing, scenic art, properties, stage mechanics and electricity, and the work is done largely at the various theaters, The report concludes with a list of teachers (and how strange it sounds to one accustomed to American ideas of “education”!)— M.P. Zandin, scenic director of the Maryinsky Theater—scenic decoration; S. A. Yevsetjev, director of properties-shops of the Maryinsky Theater—properties; F.P. Graff, technical director of the Maryinsky Theater, stage technique,” etc.

Another report deals with theatrical performances at shops and factories. “Many shops and plants in Moscow give their own performances. These, though of an amateur character, are a source of inspiration to the workers of local factories, who are the actors at these performances.

“Especially successful were the performances at the Einem Chocolate Factory.

“Performances have also been given at Zindel’s shops, Prochotov Dry Goods, etc. At the latter, dramatic courses have been opened for workers wishing to receive dramatic education.”

We have quoted at some length these accounts of Soviet theatrical activities, for the sake of the emphasis they give to the view, so novel to the general public in this country, of the theater as the very basis of education. If education is to mean a learning of the art of living, it must begin at the very beginning, and teach men and women to enjoy themselves—the absence of which knowledge makes alcohol the sinister necessity it is at present to our sad and soggy population! —to be children again, to play, to have beauty, to have art, and to share deep emotions with others. Upon this foundation alone can there be securely built in the masses the fabric of common aspiration and common knowledge and common struggle for the greater freedom and wisdom and happiness which the future holds…

But since the printed word is the chiefest liberator of the human soul, it will be appropriate to conclude this account with the report of the Literary Publication Board of the Commissariat of the Peoples Education. “On December 13, 1917, at a session of the Literary Publication Board a committee was named to draft a decree ordering the establishment of a Technical Board to take charge of state printing shops, including all those printing shops which had been nationalized after the October revolution. This committee was composed of representatives from the Literary Publication Board, the Commissariat of the Interior, Printers’ Trade Union, and a committee of workers employed in state printing shops.

“In February, 1918, owing to energetic activity, of the Soviet and representatives of the printing trades, publishing business on a large scale was made possible. The state commission on Education made up a list of Russian novelists, poets and critics, whose works were declared a state “monopoly for five years. This list includes the names of over fifty Russian classics, such as Soloviev, Bakunin, Bellinski, Garshin, Hertzen, Gogol, Dostoevsky, Kolzev, Lermontov, Nekrasov, Pushkin, Tolstoi, Turgeniev and Tchekov, and others.

“On July 4th at Moscow there was established a committee on Literature and Art. Among its members are the writer V. Bruisov and the painter V. Grabar.

“A committee was also formed to publish popular scientific books. This committee has two sections—political economy and natural science. The latter includes Professors Timiriazov, Michailov, Wolf, Walden, and others.

“A number of brochures, original and translations, have been already published by the committee, the subjects being astronomy, physics, meteorology, botany and pedagogy. As regards the publication of text-books, the state Commission already on Dec. 4, 1917, created a special commission to take charge of the work.

“A semi-annual appropriation of 12 million rubles has been granted to the Literary Publication Board. The appropriation for the second half year may reach 20 millions.”

This was the beginning of the literary activities of the Soviet State, which have since flowered in the magnificent edition of the world’s best literature, under the editorship of Maxim Gorky, by which the greatest literary masterpieces of all ages have been made accessible, in small, beautifully printed and inexpensive volumes, to the Russian masses. We may freely assume that the same principles of selection obtain in this edition as in the selection of plays, and that the works chosen are those which will not merely acquaint the worker of Russia with the art of story-telling and the characteristics of human nature in many lands, but will above all teach him courage and confidence in his destiny, teach him with their satire to scorn the ideals of bourgeois and capitalist society, deepen his sense of community with his fellow-workers in their world-wide struggle for freedom, and make him face the future with a clear and unshakable resolution, an indomitable will to victory and freedom. It is the most stupendous single educational enterprise ever. ventured upon by any State; and it is a part of the most far-reaching plan for intellectual emancipation in human history. These efforts and these accomplishments would have been impossible without the generous and devoted co-operation of many minds —”one common wave of thought and joy lifting mankind again.” But they were set on foot, initiated at the most desperate moment of the Revolution—as these documents bear witness—by Nicolai Lenin. To his realistic, scientific, patient and undiscouraged faith in, the possibilities to be achieved by education, we owe, so far as we may be said to owe a revolutionary renaissance to any one individual, the example which Russia amid her agonies has set for us all over the world to follow.

The Liberator was published monthly from 1918, first established by Max Eastman and his sister Crystal Eastman continuing The Masses, was shut down by the US Government during World War One. Like The Masses, The Liberator contained some of the best radical journalism of its, or any, day. It combined political coverage with the arts and a commitment to revolutionary politics. Increasingly, The Liberator oriented to the Communist movement and by late 1922 was a de facto publication of the Party. In 1924, The Liberator merged with Labor Herald and Soviet Russia Pictorial into Workers Monthly.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1919/06/v2n06-jun-1919-liberator-hr.pdf