Chicago has long been a center of the U.S. labor movement, in both its best and worst traditions. In this fantastic article on a history he was deeply involved with, Foster looks at what made the Chicago Federation of Labor under John Fitzpatrick so effective in organizing that city’s industries, how it cleaned out the bureaucrats, and took the lead on larger class question like political prisoners and a Labor Party. Foster traces the history of the Federation’s role in the major Chicago class battles of that time in the garment, packinghouse, newspaper, and steel as well as its leadership.

‘The Chicago Federation of Labor’ by William Z. Foster from Labor Herald. Vol. 1. No. 10. December, 1922.

IN the dismal prospect of the generally reactionary American labor movement, one of the bright spots is the Chicago Federation of Labor. For many years past this body, counting as adherents 300,000 trade unionists in the Chicago district, has been noted throughout the country for the cleanness of its leadership and the progressivness of its policies. Time after time, it has sounded the real proletarian note in the hour of bitter struggle. Again and again it has blazed the way along which the backward American working class must eventually follow. The Chicago Federation of Labor is a stimulus and encouragement to every true fighter in the cause of Labor.

Cleansing the Federation

It is no accident that the Chicago Federation of Labor is progressive. It is because the honest elements in that body, in the years gone by, broke the power of the sinister forces that curse and degrade Organized Labor in many large cities, and thus gave the healthy phases of unionism a chance to flourish. The time was when the Federation was ruled by a corrupt gang of labor fakers, with the notorious, czarlike “Skinny” Madden at their head. Terrorism and graft were the order of the clay, and the workers suffered accordingly. But the Federation was fortunate in having in its midst a body of real fighting trade unionists, such as John Fitzpatrick, Edward Nockels, Anton Johannsen, T.P. Quinn and many others, who challenged the autocracy of Madden arid finally destroyed it. Their victory was won, however, only after one of the bitterest and hardest fought internal battles in the history of Organized Labor.

Martin B. Madden, better known as “Skinny” Madden, was one of the most remarkable figures ever produced by the labor movement. He was only a steamfitter’s helper, but he overcame this handicap of being an unskilled worker and secured a tremendous grip upon the organized skilled tradesmen of Chicago. Bold, courageous, and an organizer of unquestioned ability, he gathered around himself a machine of gunmen and thugs, which he used ruthlessly to further his limitless schemes of corruption. He and his crowd ruled the labor movement with a rod of iron. “Skinny” Madden was the symbol of terrorism and extortion in Labor’s ranks.

The inevitable reaction against Madden’s reign of organized graft took place in I905. Led by Fitzpatrick, Nockels, and others, the honest elements in the Chicago Federation declared war against Madden. Except for a few, these insurgents were not radicals. Had they been such, the cleansing of the Federation would not have taken place at that time, for doubtless they would have been affected by the run-away policy of dual unionism and would have left Madden undisturbed in his control. But they were trade union fighters, unaffected by secessionism, and they stood their ground. Madden tried to terrorize them. On one occasion eight of his men with drawn guns held up an election committee in broad daylight, and beat Mike Donnelley, president of the stockyards union, so badly that he never fully recovered. For months the most intense excitement prevailed, and astounding acts of violence were perpetrated by Madden to break up the opposition. But, unterrorized, the rebels went ahead with their agitation, stirring up the rank and file in favor of a clean Federation. The fight, so fateful to Chicago labor, came to a conclusion in 1900, when John Fitzpatrick was elected President of the Federation in the face of the most desperate opposition of the Madden gang. This definitely broke the power of the corruptionists (they are now entrenched in the Building Trades Council), and it laid the basis for the progressive administration which has characterized the Federation ever since.

A Record of Progress

John Fitzpatrick, President of the Chicago Federation of Labor, is one of the sturdy oaks of the labor movement. Honest, capable, and fearless, he is deeply hated by the labor-crushing elements in Chicago. He has also long been the despair of the local labor crooks. His co-worker, Secretary E. N. Nockels, who was elected in 1903, and has served in his office continuously since then, is another remarkable type of militant, progressive trade union leader. Together the two, Fitzpatrick and Nockels, make up a team which, for co-operation and harmonious, effective action, is hardly to be equaled in any labor office in America. The friendship between them, the lack of jealousy, and their unity upon all vital issues, are proverbial in Chicago.

Time and again, during the long administration of Fitzpatrick and Nockels, the Chicago Federation of Labor has demonstrated its real proletarian spirit. A notable event in its history was the great clothing strike of 1910, when 50,000 sweated slaves revolted against their masters. The strike was under the jurisdiction of the United Garment Workers, but Rickert, as usual, deserted the strikers. The burden of carrying on the struggle fell upon the Chicago Federation of Labor, which instituted an elaborate commissary system, and was directly responsible for such success as was had in the battle. The final betrayal of the strike by the officials of the United Garment Workers directly led to the formation of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers a few years later. In the struggles of the Ladies’ Garment Workers, the Federation also took an active part in establishing that organization. This some of the Ladies’ Garment Workers’ officials are now conveniently trying to forget. Because of its loyal, unstinted, and altogether unusual support, the Chicago Federation of Labor played a tremendous part in organizing the garment trades of Chicago.

Another historic struggle in which the Federation distinguished itself was that of the newspaper pressmen in 1912. This was one of the bitterest fought strikes in the whole record of the Chicago labor movement. The attitude of the International officials of the printing trades was hostile to the struggle which was it was pretty much a rank and file affair. The leader was L.P. Straube of the stereotypers’ union. Because he was instrumental in bringing his union to the support of the pressmen, he was later expelled and denied the right to make a living in union shops. The Federation fought his case for years, carrying it to the floor of the A.F. of L. Convention in 1915, and making even Sam Gompers back up on the proposition. For a time it appeared that the Federation would lose its charter because of its militant stand, even as had happened in a similar struggle a few years before.

The Mooney Case

The Chicago Federation of Labor has always particularly distinguished itself by rallying to the support of militants imprisoned or harassed by the enemy. In the great McNamara case, and that of the other officials of the Structural Iron Workers’ Union who were arrested in connection therewith, the Federation was so active that the iron workers’ union presented both Fitzpatrick and Nockels with gold watches in appreciation. In many other such cases, similar activity is displayed. A notable instance was in the case of Leon Trotzky, who, trying to return from America to Russia, was detained by the British authorities at Halifax. At that time Trotzky was to us merely an unknown Russian Jew. But the Federation raised its voice in protest at his detention. The support of Sacco and Vanzetti, of Jim Larkin, and of the latest Michigan cases, is typical of the spirit of the Federation.

From its very inception the Mooney-Billings Case has been a particular ward of the Chicago Federation of Labor. It was the first important labor organization in the United States which recognized the dastardly frame-up involved and its consequences to Labor. While the San Francisco Central Labor Council, and many other organizations that should have been active, were sound asleep, the Chicago Federation of Labor was holding great meetings of protest. One, in the Colliseum, assembled fully 20,000 people. Besides this, the Federation has taken an active part in handling the case. Ed Nockels personally unearthed the famous Oxman letters. Likewise, he was directly instrumental in securing the confession from McDonald, the notorious stool-pigeon witness against Mooney. Had the rest of the labor movement displayed a fraction of the interest and solidarity shown in this case by the Chicago Federation of Labor, Mooney and Billings would long ago have been free men.

The Packinghouse Campaign

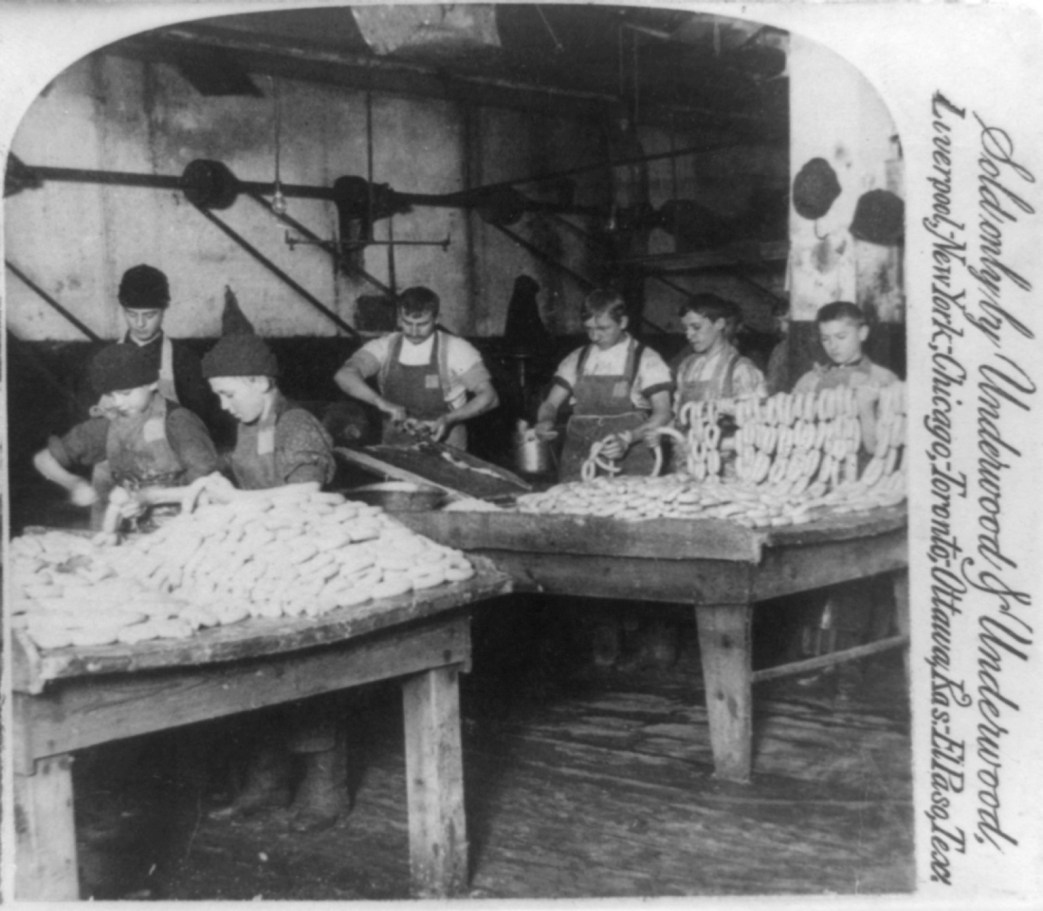

In all the struggles of the packinghouse workers to strike the shackles of slavery from their limbs, the Chicago Federation of Labor has played a leading part. Its most notable achievement in this respect was the carrying through of the national organizing campaign in the packing centers during the war. Both the A.F. of L., and the Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butcher Workmen, had shown themselves entirely incompetent, with their antiquated craft union methods, to organize the downtrodden packinghouse workers.

Then the Chicago Federation of Labor itself took hold. The Butcher Workmen were broke and the Federation furnished the money to begin the campaign. It also sounded the note of industrialism, and lined up the dozen trades of the industry, all into one cooperating organization. A general drive was started, with the result that the packinghouse workers responded en masse. The movement spread to other centers. The local federation of trades, known as the Stockyards Labor Council, developed into a national alliance to correspond. The national movement, headed by John Fitzpatrick, culminated in a sweeping victory for the workers and their organization 100% in all the principal packinghouse centers of the United States. Where the A.F. of L. itself, and the International Unions had failed to make good, the Chicago Federation of Labor won an overwhelming success.

The Steel Campaign

Hardly was the epoch-making packinghouse campaign at an end than the Chicago Federation of Labor launched another of still greater importance, namely that to organize the workers in the steel industry all over the country. Here was another instance of the total failure of the A.F. of L. and the International Unions with jurisdiction. They were absolutely helpless to handle the situation. It took a central labor council, a type of organization which they superciliously despise, to teach them how to do a real job of organizing.

A resolution was adopted by the Chicago Federation on April 7, 1918, calling for a general campaign of organization in the steel industry by all the trades involved. This was forwarded to the general office of the A.F. of L., which, in harmony with its usual do-nothing policy of incompetency, allowed the call to go unanswered. Then, to force action of Gompers, the resolution was readopted by the Federation and introduced by its delegate into the St. Paul Convention of the A.F. of L. There it was carried, doubtless in the hope that it would result in nothing. But, with its usual determination, the Chicago Federation pushed the matter and the great campaign got under way. As in the case of the packinghouse workers, the drive to organize the steel workers was a striking success. Although, when the campaign opened, the International Unions with their obsolete craft tactics had not succeeded in assembling a handful of men anywhere in the industry after years of effort, the Chicago Federation drive resulted in bringing 250,000 workers into the unions, notwithstanding desperate opposition on the part of the companies. Again the Chicago Federation of Labor, by stressing the principle of solidarity and action along industrial lines, taught the A.F. of L., and the International unions how to organize. Both of its campaigns, in the packinghouses and in the steel mills, blazed the way for inevitable industrial unionism.

The Farmer-Labor Party

True to its inherent spirit of progress, the Chicago Federation of Labor was also a pioneer in the field of working-class politics, even as it was in that of industrial action. No community in the United States has suffered more than Chicago from the evils of Gompers’ stupid policy of “rewarding Labor’s friends and punishing its enemies”; no labor movement has felt more keenly its baneful and poisonous influence. Recognizing the logic of the situation, and despite the bitter opposition of the old guard, the Chicago Federation of Labor raised the banner of independent working-class political action. During November, 1918, it launched the Labor Party, which later became the Farmer-Labor Party. Naturally, Mr. Gompers and his adherents have sabotaged this organization, even as they do all others of a progressive character. Although the Farmer-Labor Party itself has not been a great success in a political way, the idea behind it has made steady headway. It is not too much to say that the whole labor movement is now moving in the direction politically which the Chicago Federation of Labor pointed out four years ago that it would have to travel. It should have been the duty of the A.F. of L. general office to launch such a movement, but, as in the case of the steel and packinghouse drives, it fell upon the Chicago Federation to do so.

Federated Press and Co-operation

One of the keenest needs of the trade union movement is an efficient news gathering agency to supply the facts of the labor struggle to the journals of the various labor organizations. Of course, the office of Mr. Gompers did nothing serious to supply this need. But the Chicago Federation of Labor, in the measure of its opportunity, did. Robert M. Buck, the editor of its official journal, The New Majority, acting in close co-operation with the heads of the Chicago Federation, took an active part in founding and carrying on the Federated Press. This organization is unquestionably the best labor news gathering agency in the world. And naturally enough its principal enemy is the old guard controlling the A.F. of L.

The Chicago Federation of Labor has always been a militant advocate of co-operation in industrial and mercantile enterprises. During 1919, it was instrumental in establishing the National Consumers’ Co-operative Association, the organization which handled the supplies for the commissaries in the great steel strike of that year.

Amalgamation

One of the latest forward-striving movements of the Chicago Federation of Labor, and one which made something of a sensation throughout the ranks of Organized Labor, is the · present amalgamation campaign. The Chicago Federation, continuing the thought behind the steel and packing drives, believes the time has come when the craft unions must combine themselves into industrial organizations. Therefore on March 25, of this year, it adopted a resolution embodying this proposition and sent it forth to Labor. Great commotion ensued in the ranks of the reactionaries. Even Mr. Gompers himself came to Chicago to block this move, so dangerous to the rich jobs of many officials. But they could not stop it and they hesitated before taking drastic action. They knew well that the principle of amalgamation enunciated by the Federation fitted the needs of the time and found a hearty response among the rank and file. Since its beginning by the Chicago Federation, the amalgamation campaign has been making great headway all over the country. Large numbers of organizations, as detailed in last month’s LABOR HERALD, have endorsed it. Without doubt the movement will eventually result in modernizing the trade unions generally. It is one more instance of the Chicago Federation of Labor sensing the need of the situation and responding accordingly, while the high-paid trade union officialdom at Washington slumbers and vegetates.

Russia

The Chicago Federation of Labor has never agreed with the reactionary policy of Sam Gompers towards Russia. On the contrary, it has felt from the beginning the true working-class character of that great upheaval, and has steadfastly adhered to a policy of friendliness, and a desire to see the great experiment tried out under the best of conditions. The Chicago Federation has consistently demanded the recognition of Soviet Russia, and also that trading be established with that country. It has lent loyal and unstinted aid in the collection of funds for the famine-stricken. It was one of the first central labor councils of the United States to endorse the Friends of Soviet Russia in the latter’s relief campaign. A striking illustration of the Federation’s keen understanding of the Russian situation was had recently when it refused, by a unanimous vote, to adopt a resolution demanding the release of the Social-Revolutionaries being tried in Moscow. Every real working-class fight, no matter in what country or under what flag, can depend upon the support of the Chicago Federation of Labor.

Because of its long progressive and militant record, many people throughout the country have got the idea that the Chicago Federation of Labor is a radical organization. But this is not the case. It is just a healthy, vigorous, natural labor movement, such as would exist in every center were it not for the killing influence of the Gompers machine. The Chicago Federation has many weaknesses, as all admit. But if the rest of the trade unions were on a par with it we would not have the sad spectacle of the American labor movement so far behind the rest of the international organized working class. It would be where it belongs, in the very forefront of the struggle against world-wide capitalism.

The Labor Herald was the monthly publication of the Trade Union Educational League (TUEL), in immensely important link between the IWW of the 1910s and the CIO of the 1930s. It was begun by veteran labor organizer and Communist leader William Z. Foster in 1920 as an attempt to unite militants within various unions while continuing the industrial unionism tradition of the IWW, though it was opposed to “dual unionism” and favored the formation of a Labor Party. Although it would become financially supported by the Communist International and Communist Party of America, it remained autonomous, was a network and not a membership organization, and included many radicals outside the Communist Party. In 1924 Labor Herald was folded into Workers Monthly, an explicitly Party organ and in 1927 ‘Labor Unity’ became the organ of a now CP dominated TUEL. In 1929 and the turn towards Red Unions in the Third Period, TUEL was wound up and replaced by the Trade Union Unity League, a section of the Red International of Labor Unions (Profitern) and continued to publish Labor Unity until 1935. Labor Herald remains an important labor-orientated journal by revolutionaries in US left history and would be referenced by activists, along with TUEL, along after it’s heyday.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborherald/v1n10-dec-1922.pdf