In 1932-33 Langston Hughes toured Soviet Central Asia where he spent time in Turkmenistan among the peasant cotton growers and contrasts their new lives to those growing cotton back home in the Southern United States in this marvelous essay.

‘White Gold in Soviet Asia’ by Langston Hughes from New Masses. Vol. 12 No. 6. August 7, 1934.

IN THE autumn, if you step off the train almost anywhere in the fertile parts of Soviet Central Asia, you step into a cotton field, or into a city or town whose streets are filled with evidences of cotton nearby. The natives call it “white gold.” On all the dusty roads, camels, carts, and trucks loaded with the soft fibre go toward the gins and warehouses. Outside the towns, oft-times as far as the eye can see, the white balls lift their precious heads.

The same thing is true of the southern part of the United States. In Georgia and Mississippi and Alabama you ride for hundreds of miles through fields of cotton bursting white in the sun. Except that on our roads there are no camels. Mules and wagons bear the burdens.

About two years ago, when I was in the South all winter, I spent some time in Alabama, fifty miles or so from world famous Scottsboro. I wanted to visit the big cotton plantations there. “It’s dangerous,” my friends said. “The white folks don’t like strange Negroes around. You can’t do it.”

But I finally managed to do it-and this is how: During the December holidays, I went with a section of the Red Cross (a Negro section, of course, as everything is segregated in the South) to distribute fruit to the poor the POOR meaning in this case the black workers on a rich plantation nearby.

We set out in a rickety Ford and drove for miles through the brown fields where the cotton had been picked. We came to a gate in a strong wire fence. This passed, some distance further on we came to another fence. And then, far back from the road, huddled together beneath the trees, we came upon the cabins of the Negro workers- cheerless one room shacks, built of logs. A group of ragged children came running out to meet us.

The man with the Red Cross button descended from the car and spoke to them in a Sunday-school manner. He asked them if they had been good, and if they had gotten any presents for the holidays. Yes, the children said, they had been good, but they hadn’t gotten any presents. They reached out eager little hands for the apples and oranges of charity we offered them.

We went into several of the huts, and while the Red Cross man talked about the Lord, I asked a few questions. I asked an old man if the cotton had been sold. He answered listlessly, “I don’t know. The boss took it. And even if it has been sold, it don’t make no difference to me. I never see none of the money nohow.” He shrugged his shoulders helplessly and sucked at his pipe. A woman I spoke to said she hadn’t been to town for four years. Yet the town was less than fifteen miles away. “It’s hard to get off,” she said, “and I never has nothing to spend.” She gave her dreary testimony without emotion. The Red Cross man assured her that God would help her and that she shouldn’t worry.

A broken-down bed, a stove, and a few chairs were all she had in her house. Her children were among those stretching out their skinny arms to us for charity fruit. Yet the man who owned this big plantation lived in a great house with white pillars in the town. His children went to private schools in the North and traveled abroad. These black hands working in white cotton created the wealth that built his fine house and sup ported his children in their travels. A woman who couldn’t travel fifteen miles to town was sending somebody else’s child on a trip to Paris. Thus, the base of culture in the South. Economists call it the share-crop system.

Ironical name- for cotton is a crop that the Negro never shares. The plantation owner advances every month a little corn meal and salt meat from the commissary, gives seed and a cabin. These advances are charged to the peasant’s account by the plantation bookkeeper. At the end of the year when the cotton is picked, the plantation owner takes the whole crop, tells the worker his share is not large enough to cover the rent of the cabin, the cost of the seed, the price of the corn meal and fat meat, and the other figures on his book. “You owe me,” says the planter. So the Negro is automatically in debt, and must work another year to pay the landlord. If he wishes to take his family and leave, he is threatened with the chain gang or lynchterror.

How different are the cotton lands of Soviet Central Asia! The beys are gone-the landlords done with forever. I have spoken to the peasants and I know. They are not afraid to speak, like the black farm-hands of the South.

It was the height of the picking season when I visited the Aitakov Kolkhoz near Merv. The Turkmen director took us to the fields where, in the bright morning sun, a brigade of women were picking cotton, moving rapidly through the waist-high rows, some stuffing the white bolls into the bosoms of their gowns until they were fat with cotton, others into sacks tied across one shoulder. Thirty-two kilos of picked cotton was counted a working day, but the udarniks picked sixty-four kilos or more a day. And many of the women I was watching were udarniks. This brigade had fulfilled 165 percent of its plan, according to the director of the farm. In their beautiful native dresses of red and green with their tall headdresses surmounting mooncolored faces, these women moved like witches of work in a sweeping line down the length of the broad field, taking the whiteness and leaving the green-brown stalks, stuffing into their sacks and bosoms the richness of the earth.

On this particular day, while the women worked in the fields, the men were repairing the irrigation canals near the main stream, the director told us. But the men also pick cotton when there is no heavy work to do.

I remarked at the absence of children in the fields. In our American South they would be picking along with the parents. “Here, they are in school,” the director said. “Our kolkhoz has a four-year school. And in the village nearby there is a school for five hundred pupils where the older students go. There is a teacher here for the grown-ups, too. You will see during the rest period.”

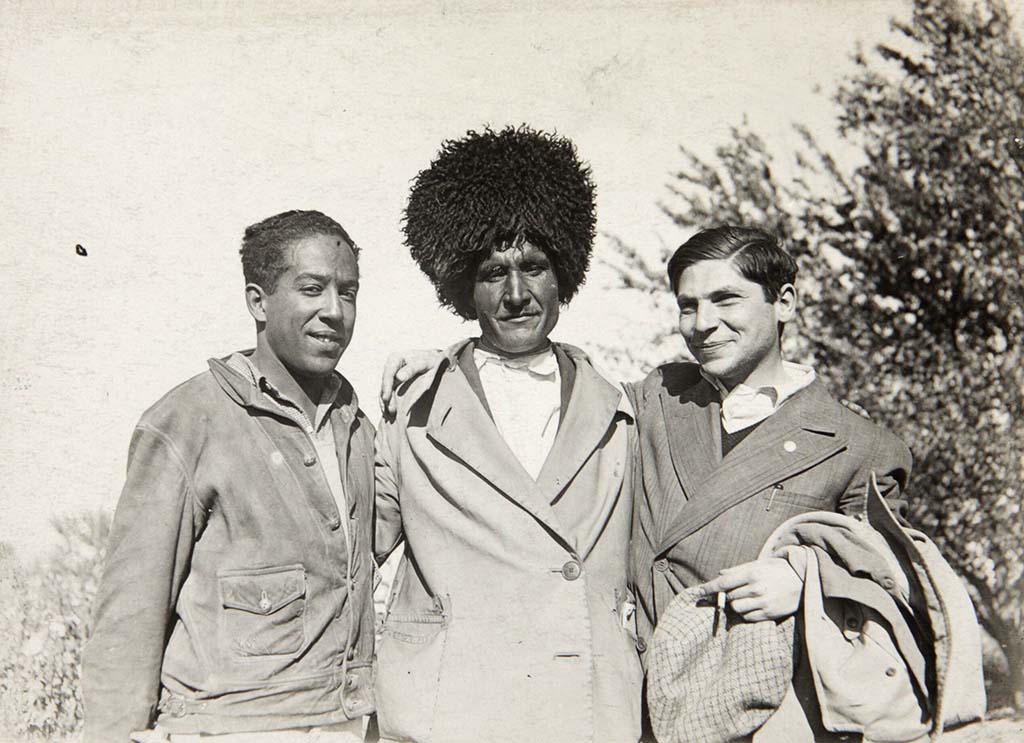

The director went away and left us with the time-keeper and his assistant, a young student learning to keep the books. They were both Turkmen with marvelously high black hats of shaggy lamb’s skin towering above their heads. With them I could not speak a word. My bad Russian did not work. But Shali Kekilov, the poet of the Turkmen Proletarian Writer’s Union, translated. We sat on the grass under the fruit trees bordering a dry canal and learned the facts about their kolkhoz, and the success of collectivization in their districts. Within the village radius of eight kilometers, out of a population of 2,700 people, only twenty individual farmers remained. On the Kolkhol Aitakova itself there were 230 workers, ten of them members of the Communist Party, and eleven candidates. (Two of the Party members were women; and two women were candidates.) There were twenty-eight Komsomols, or Young Communists League associates.

When the rest period came, a boy brought tea and bread to the fields. The women sat in a group on the grass and, as they ate, a girl teacher moved among them with a book, helping each woman to read aloud a passage- thus they were learning to read, a thing that in all the long centuries before, women in Central Asia had never done.

The men sitting on the grass with us were proud. “Before the Revolution there weren’t twenty-five women in the whole of Turkmenia who could read. Now look!” A woman peasant sat on the edge of the cotton field talking out of a book. Something 10 cry with joy about! Something to unfurl red banners over! Something to shout in the face of the capitalist world’s colonial oppressors. Something to whisper over the borders of India and Persia.

In the afternoon, I helped pick cotton, too, for the fun of it. Then a young man came to take us to the tea-house for dinner. There I answered man questions concerning the Negroes in America. It was dusk when we walked across the fields to the cluster of buildings that formed the center of the kolkhoz. They were preparing the nursery as a guestroom for us, moving back the little chairs and tables of the children and spreading beautiful hand-woven rugs on the floor that we might sit down.

Soon guests began to arrive, teachers from the village school came, and then the men who had been out on the irrigation works all day, and among them musicians. They came in twos and threes and larger groups until the room was full. One oil lamp on the floor was the only light, and as they sat around it, their tall hats cast tremendous shadows on the walls. Chainiks of tea were brought, and a half-dozen bowls were shared by all. As the teapots emptied, they were passed continually back and forth from hand to hand to the door where a man replenished them from the water boiling over an open fire outside in the dark.

Many stories were told to us there in the nursery by the men who shared their little bowls of tea; stories of the days when women were purchased for sheep or camels or gold. If you were rich enough, young women; or, if you were poor, you worked three to five years in the field to receive an old wife that some rich man had tired of. Stories were told of the beys who once controlled the water, and whose land you must till in order to moisten your own poor crops. Stories were told of feuds, tribal wars, Tsarist oppression, and mass misery. And all this not a hundred years ago, but only ten or fifteen years past. These men in the tall hats had not read about it in history books. It had been their life. And now they were free.

Then the boys began to sing to the notes of their two-string lutes. The high monotonous music of the East filled the room. Two singers sat cross-legged cm the floor, face to face, rocking to and fro. One was the young man who, during the day, learned to be a time-keeper. The other, a peasant who, between verses threw back his head and made strange clucking sounds with his throat. They sang of the triumphs of the Revolution. Then they sang old songs of power, of love, and the beauties of women whose faces were like the moon. Sometimes they played, without singing, music that was like a breeze over the desert, coming out of the night to the cotton fields.

A sheep had been killed and, from the fire outside, great steaming platters of mutton were brought which we ate with our hands. Most of the men left at midnight, but several remained to keep us company, and slept on the floor with us. For a while I sat up by the single oil lamp writing into my notebook.

I visited several other cotton kolkhozes in Turkmenia and Uzbekistan, and one sovkhoz. I filled two notebooks with figures and data: the number of hectares under cultivation, the yield per hectare, the percentages fulfilled according to the plan-some not always good the method of irrigation, the amount the state pays for cotton in rubles and wheat and cloth and tea. I stayed for two days at the mechanization station for farm machinery near Tashkent; and another day at the seed selection station where a number of American Negro chemists are employed at work they would seldom be allowed to do in the United States. I saw the cotton college. I visited the big building of the Cotton Trust at Tashkent; I looked at statistics. I studied charts.

The figures, sooner or later (important as they are) I shall forget. Maybe I will lose the notebooks in my travels. But these things I shall always remember that the peasants themselves have told me: “Before, there were no schools for our children; now there are. Before, we lived in debt and fear; now we are free. Before, women were bought and sold; now no more. Before, the water belonged to the beys; today, under the Soviets, it’s ours.”