Introduction by Revolution’s Newsstand.

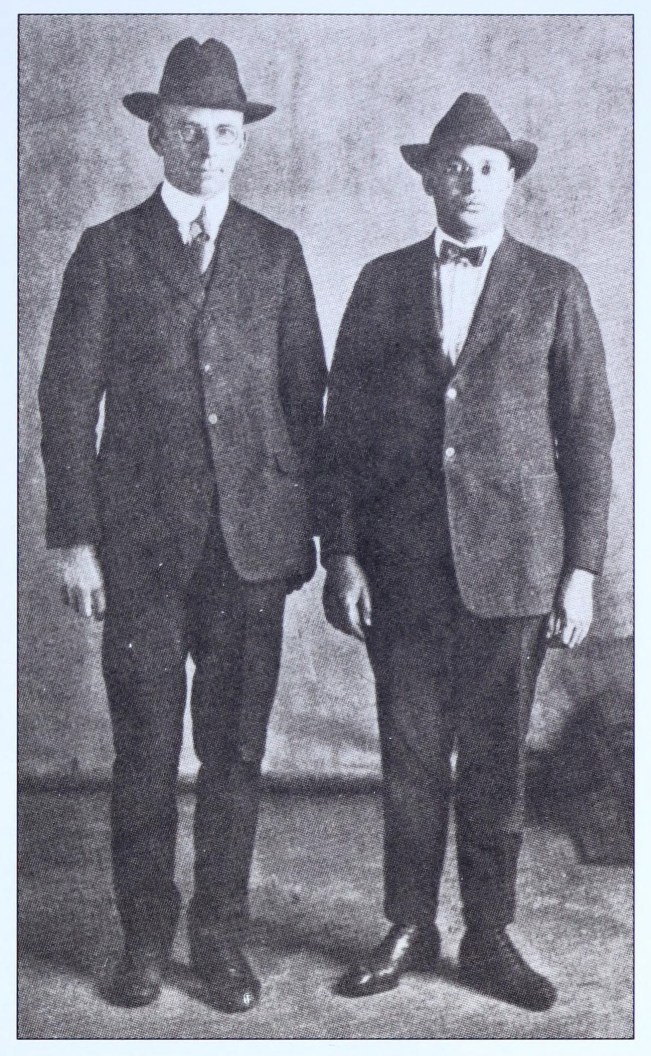

An essential historic document of our movement. Isaac Edward Ferguson provides a detailed, defining account of the founding of the (old) Communist Party of America. With William Bross Lloyd, Ferguson established among the first explicitly pro-Bolshevik groups, the Communist Propaganda League in Chicago, serving as one of the organizers of the national Left Wing Conference to unite the emerging forces at a June, 1919 conference to prepare for that September’s Emergency Socialist Party Congress. There Ferguson was elected National Secretary of the formalized Left Wing.

However, The Left Wing meeting was divided into several tendencies which would split and purse very different policies at the 1919 convention, leading to three distinct Communist formations: the Communist Labor Party, the Proletarian Party, and the this (old) Communist Party of America. Within the CPA conference, tree divergent tendencies were represented; the Russian Federation and allies lead by Alexander Stoklitsky, the Rutherberg-Lovestone-Ferguson Left Wing Council group, and the Michigan-Chicago based Proletarian University. The Proletarians left immediately, while the split between the Language Federations and the Ruthenberg supporters occurred the following spring with Ruthernberg’s group leaving to pursue, successful, fusion with the Communist Labor Party, forming the United Communist Party.

Ferguson, a Chicago supporter of the Ruthernberg-Lovestone tendency, became a leading member of the new Communist Party of America and editor of their newspaper. Published in the pages of inaugural issue of the ‘The Communist’ immediately after, the document details a most consequential moment in our movement.

Leadership elected at the conference included, with party names and bodies they represent:

Executive Council: National Secretary: C.E. Ruthenberg “David Damon” (Cleveland), International Representative, Senior Editor: Louis C. Fraina “F.” (New York, NY), Charles Dirba “D. Bunte” (Minneapolis), I.E. Ferguson “Caxton” (Chicago), K.B. Karosas (Philadelphia) Lithuanian Federation, John Schwartz (Boston) Latvian Federation, Harry Wicks (Portland, Oregon).

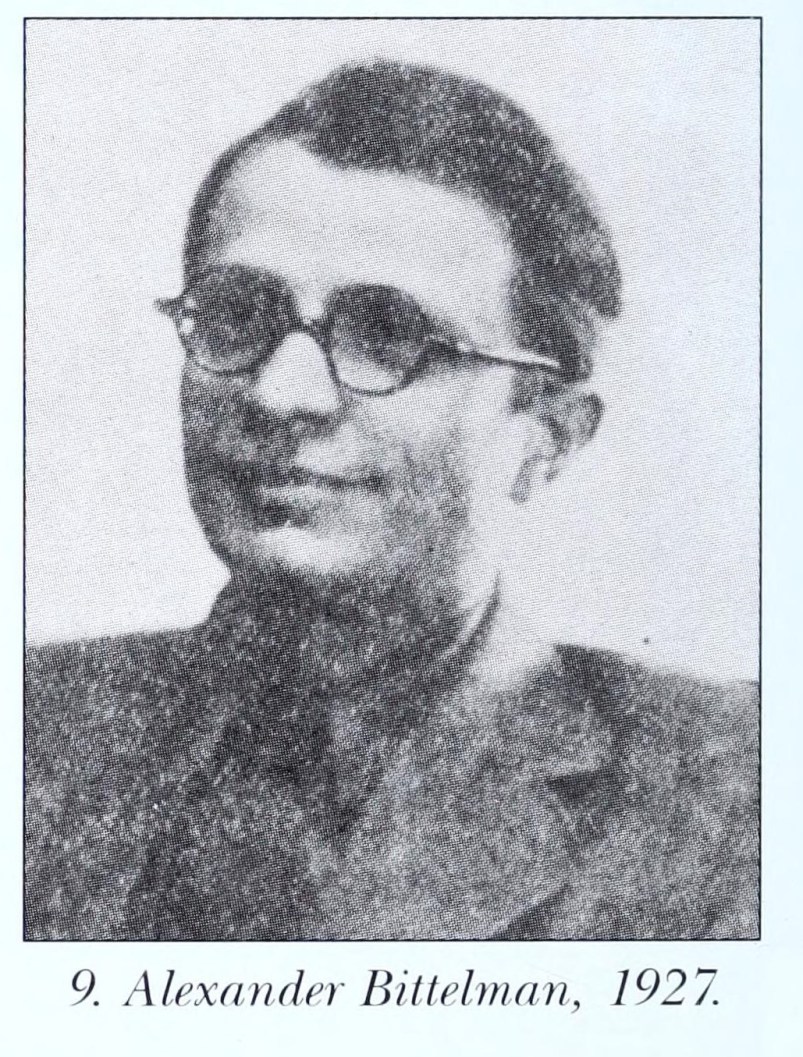

Central Executive Committee Members: John J. Ballam (Boston), Alexander Bittelman “A. Raphael” (New York, Jewish Federation) Maximilian Cohen “Charles Bernstein” (New York, NY), Daniel Elbaum (Detroit, MI) Polish Federation, Nicholas Hourwich “Andrew” (New York) Russian Federation, Jay Lovestone “John Langley” (New York), Oscar Tyverovsky “Baldwin” (New York) Russian Federation, Rose Pastor Stokes “Sascha” (New York City).

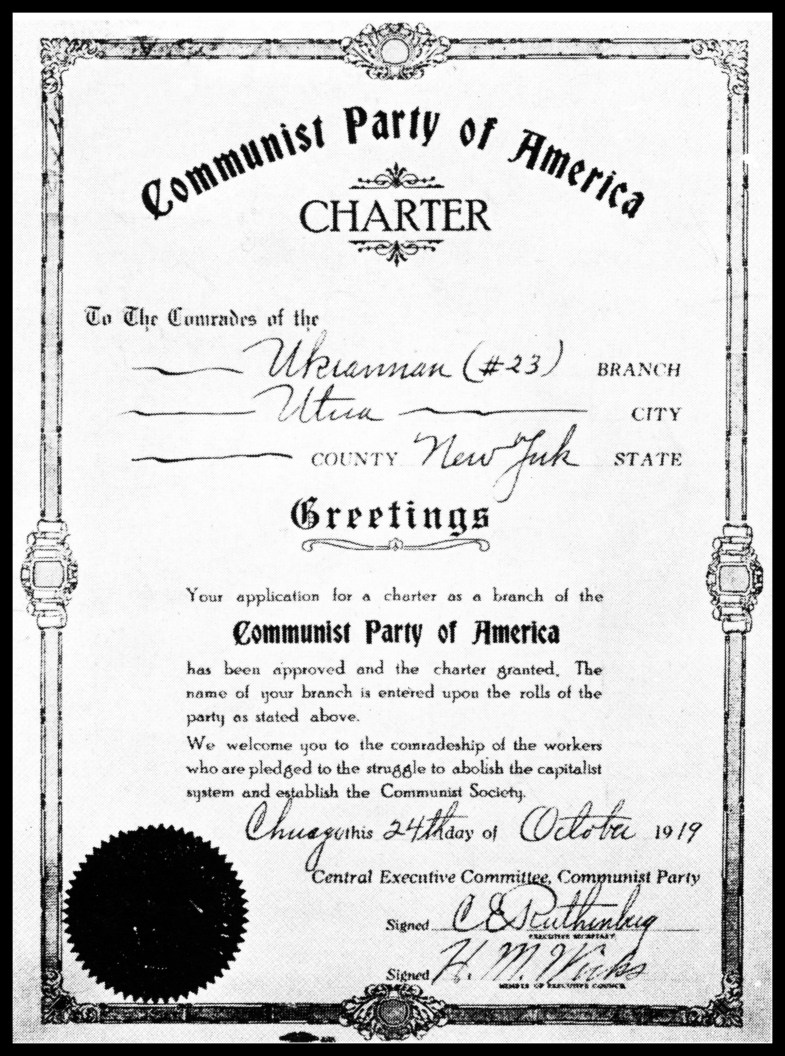

Language Federation Secretaries: Fritz “Fred” M. Friedman (German), Joseph Stilson (Lithuanian), Joseph Kowalski (Polish), Alexander Stoklitsky (Russian). Includes portraits of many participants.

‘The Founding Communist Party Convention’ by I.E. Ferguson from The Communist. Vol. 1 No. 1. September 27, 1919.

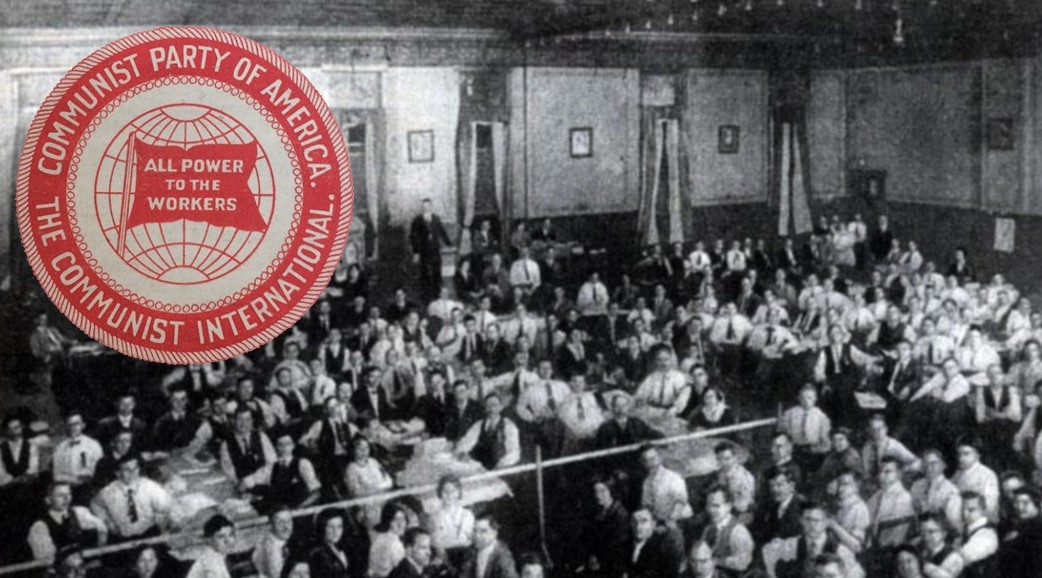

There probably never was a gathering of working-class representatives in the United States which said what it meant and meant what it said more understandingly and more resolutely than the first convention of the Communist Party. This meeting of some 140 delegates, representing fifty to sixty thousand members, was unique in the annals of American Socialism in many respects, but most apparently in the character of the Convention itself. There was an all-pervading sense of realism about the work in hand, absolute candor in interchange of argument, impossibility of compromise as the solution of any item.

Three distinct groups were marked out at the opening of the Convention, and the whole proceedings represented the balancing of these three groups against one another. The delegates who pitted themselves individually against these solid formations found themselves in a hopeless situation. Three delegates who did not quickly enough yield their impulsive individualism to the mass discipline of one or other of the three groups left the Convention. They found more congenial atmosphere in the Centrist Convention of the “Communist Labor Party,” where each was a law unto himself, and where the group as an entity was beyond the possibility of decisive action.

But in the meantime the most thoughtful of the bolting delegates from the Socialist Party Convention, who had been precipitated into a chance third party adventure, sensed that there was something unusually substantial about this quiet gathering where group power was grimly pitted against group power.

The Convention which opened with three distinct divisions ended a solid unit, none of the groups having lost enough ground to the others to make cooperation difficult. The third party gathering, opening with an ecstasy of emotional unity, frittered away of its inherent contradictions.

There was one moment which revealed the tense enthusiasm of this Convention, a moment never to be forgotten. On Monday, September 1st, near the hour of noon, an orchestra struck the first chord of “The International.” So began the Communist Party of America.

A little while before the police had compelled the removal of the red bunting with which the hall was decorated. They also ordered the removal of two handsome floral offerings, deep red roses on a background of red shaped as a flag. The police were correct according to the city ordinance. The ordinance was correct according to the best-known methods available for a privileged minority to choke off the life impulses of the masses. There must not be consciousness on the part of the masses; there must not be under-standing of the symbolism of the red flag….There was the arrest of Dennis E. Batt on Monday afternoon, in the Convention hall, on a warrant under the new Illinois sedition law. Someone called for cheers. There was stern quiet. The work of the Convention went on. This was the answer.

Dennis E. Batt of Detroit called the Convention to order in the name of the two committees which signed the Joint Call, the National Left Wing Council and the National Organization Committee (representing the minority group of the Left Wing Conference). Louis C. Fraina of New York was elected Temporary Chairman and made an address on the problems of

the Communist Party.

While the Credentials Committee was completing its task, an Emergency Committee of 19 was elected. Before the opening of the Convention the question of admitting reporters and non-party members had been raised. The Joint Organization Committee decided in favor of an open Convention, so far as space would allow.

At 9 o’clock Monday evening the Convention was declared organized. At once the group lines within the Convention were sharply drawn. The first issue to come before the body was the admission of bolting delegates from the Socialist Party Convention. This issue was reflected in the election of a Permanent Chairman. The candidate of the Federation and Michigan groups, both favoring a rigid rule of admissibility of delegates, was Renner of Detroit. The National Left Wing Council group, favoring liberal interpretation of the Joint Call with respect to the bolting delegates, nominated Ferguson. Renner was elected.

Ferguson immediately presented the motion which opened the most intense debate of the entire Convention: that a committee of five be elected to confer with the committee of five of the Left Wing delegates who had bolted the Socialist Party Convention or had been refused seats in that Convention. This motion was defeated, 75 to 31. The effect of this vote was to cut off any recognition of the bolting delegates as a body.

This situation threatened a split of the Convention. The Federation group was voting on this issue under caucus unit rule. The vote was almost evenly divided between the Federation and non-Federation representatives, but the Michigan group of about twenty was now joined with the Federation bloc. The minority consisted of practically all the delegates outside the Federation caucus and the Michigan unit, and the leadership of the minority centered in the National Left Wing Council.

The minority organized itself in caucus, but without adopting the unit rule. The minority determined to pit its moral strength against the majority which had rebuffed the Left Wing delegates. This strength consisted of the fact that the withdrawal of this minority from the work of the Convention would leave the Russian Federation group no English-speaking expression outside the editorial staff of the Detroit Proletarian, a situation which had already been found highly embarrassing.

Tuesday morning Ferguson, Lovestone, Fraina, Ruthenberg, Selakovich, Ballam, and Cohen resigned from the Emergency Committee. Comrades Paul and Fanny Horowitz resigned as Secretaries. Comrade Elbaum of Detroit, one of the strongest men in the Federation caucus, also resigned from the Emergency Committee. This was a thunderbolt in the majority camp. It is to be noted that the minority was never without Federation delegates, the South Slavic and Hungarian representatives coming in at the start, and as the situation developed Lithuanian, Polish, and Jewish Federation delegates showing that they would not tolerate anything in the nature of arbitrary Federation control of the Convention or of the new party. The minority “strike on the job” had its quick effect. The Federation caucus conceded the reconsideration of the motion for a committee of five to make a statement to the bolting delegates; also the election of Ruthenberg and Ferguson to that committee. The interplay between the two caucuses required a clearing house in the way of a Joint Caucus made up of nine members from each side. A newspaper reporter made the just complaint that a Convention run in this way rather left the spectators out of the reckoning. It meant a deliberate measuring of forces, agreement on maximum and minimum demands, and the use of the Convention floor only on the clearly formulated programs.

The “diplomatic negotiations” between the two Conventions appears elsewhere in this issue. The insistence of the Wagenknecht-Katterfeld group on joining of the two Conventions as conventions was an absolute barrier against unity. The fight for unity within the Communist Convention could be carried no further until the credentials of the bolting delegates came up for consideration. Otherwise a case would have to be made for the admission of about 40 delegates who represented no membership, or were without any instructions upon which they could accept the Joint Call, or were open opponents of the Joint Call or of the Left Wing program. Those who talked about unity while making such a demand showed themselves to be either without sincerity or without conception of the fact that a real Communist Party could only be started upon the basis of Communist principles and

Communist membership.

With the issue of the new delegates out of the way, there was a realignment of the three groups in the Convention. Now the separation was on matters of party program and organization, and this separation reflected itself also in the Convention elections. The Michigan bloc of 20 remained in a hopeless minority at all times.

The work of the various committees speaks for itself in the documents published in this issue. The main business of the Convention was the formation of a program and of a constitution. The Program Committee consisted of Comrades Fraina, Elbaum, Stoklitsky, Hourwich, Bittelman, Batt, Cohen, Lovestone, and Wicks; the Constitution Committee: Hiltzig, Ruthenberg, Ashkenudzie, Ferguson, Tyverovsky, Stilson, Forsinger.

There are a number of features of the constitution which mark the sharp distinction between the Communist Party and the Socialist Party. Membership is not merely a matter of dues-paying in the new party, but depends on active participation in the party work and acceptance of party discipline.

A clause which precipitated a lively debate was Section 7 of Article III, barring from membership any person “who has an entire livelihood from rent, interest, or profit.” The Committee divided four against three on this provision, with Comrade Stilson presenting the side of the minority for himself, Ruthenberg, and Ferguson. The majority argument, as made by Com. Hourwich, was that the provision may be unscientific but that it is hard to convince the workingman that exploiters of labor are themselves to be trusted in the fight against exploitation. The minority argument was that such a mechanical clause could only operate to exclude the few exceptional individuals whose consciousness is not controlled by personal interest in the capitalist system. The clause easily carried.

A motion “that no member of a religious organization shall be eligible to membership” was tabled. However, a resolution was later adopted stating the attitude of the Convention on the subject of religion. Section 9 of Article III also was the subject of lively debate. This clause bars members of the Communist Party from contributing political or economic articles to publications other than those of the Party, except as to scientific journals. An attack on the party in the bourgeois press may be answered by leave of the Central Executive Committee.

The principle of centralization pervades the constitution. The new party is built on simple lines of central control, with ample counter provisions for referendum and recall. A distinct innovation is the District unit of organization, which is intended to combine or divide the States according to industrial centers. The Federations are retained as administrative units of the party, and all language branches must be- long to a single Federation of the one language. A sharp controversy arose on the question of expelling Federation branches, and this was an instance where the Federation caucus went down to defeat. The question was on the power of the City Central Committee to expel language branches; also on the question of the right of the City Central to review Federation expulsions prior to appeal to the Central Executive Committee. The function of the City Central was saved in both instances; and in every case of expulsion or of refusal of admission of a branch to membership, there is a final appeal against the decision of the Federation executives to the Central Executive Committee.

Undoubtedly the whole subject of Federations was more carefully and thoroughly discussed in these proceedings than in any other Socialist gathering in recent years.

The Central Executive Committee is made up of 15 members, elected from the National Convention. Also the Secretary and Editor are chose by the Convention. There is an Executive Council of 7 made up of the Secretary, Editor, and 5 members of the Central Executive Committee, these members to live in the city of the national headquarters or in adjacent cities.

Another innovation is the requirement that State Conventions shall be held annually in April or May. This corresponds to the fixing of the National Convention in June, with the provision for election of delegates to the National Convention by the State Conventions.

Membership qualification for all offices or nominations to public offices is set at two years. Eligibility on June 1, 1920, depends on joining the party before January 1st, 1920.

All referendums are by petition of 25 or more branches representing 5% of the party membership; or by initiative of the Convention or of the Central Executive Committee. There are no automatic referendums, as in the case of the Socialist Party election and constitutional referendums. The recall petition has the same requirements. It is specially provided that the party press shall be open for discussion of all referendum proposals while under consideration.

The fight on the Manifesto and Program would have been a battle royal but for the fact that the odds were so overwhelmingly against the Michigan minority. The Committee was presented with two drafts, one by Comrade Batt, the other by Comrade Fraina, the latter being an adaptation of the work of the Left Wing Conference of June. After considerable condensation, the Fraina draft was adopted by the majority of the Committee, Batt and Wicks being the minority.

On Saturday evening, the following statement from 20 delegates, 1 alternate, and 1 fraternal delegate was read: “We, the undersigned delegates, hereby publicly state our disapproval of the Manifesto and Program adopted by the Convention and of the methods used in forcing its adoption. Therefore we ask to be recorded in the minutes as not voting, either afirmatively or negatively, on the adoption of said Manifesto and Program, and as not accepting nominations for, or voting on, any party official elected by this Convention.”

As a matter of fact the Michigan Manifesto and Program never had the least chance of adoption, but that was the sum total of the evidence upon which it was charged that there was something questionable about the majority action in adopting the Left Wing Manifesto and Program. Somehow the Michigan delegates seemed to sense the incongruity of their condemnation of the majority action, because they did not withdraw from the Convention or give any indication of an intention not to work with the new party. Comrade Batt made an elaborate defense of his minority Manifesto and Program, and was answered in a masterly fashion by Comrade Bittelman of New York, editor of the Jewish Left Wing paper Der Kampf. The “Michigan” peculiarity within the general

Left Wing movement which culminated in the Communist Party is not an affair of the Michigan membership so much as it is of a small group from Detroit.

Only in the borrowing of a few new phrases and the careful gleaning of a sentence or two from Lenin does the minority Manifesto and Program show any relation to what is now going on in the revolutionary proletarian movement. Aside from these phrases the document might have been written twenty years ago, be- fore the adaptation of Marxism to the period of Imperialism.

In spite of all confusing intimations to the contrary, the long minority Manifesto and Program simply calls for the old Socialist Party tactics with elimination of demands for reforms. It is a program of pure parliamentarism with a prophesy that when the work of education shall have advanced far enough other tac-tics may be used. It makes reference to proletarian dictatorship, but with no acceptance of the process by which this dictatorship must be acquired.

The Communist program is based upon the mass struggles of today. It does not studiously calculate the magic hour when the correct understanding of Marxism will have its chance, but insists that the revolutionary struggle is a continuous process from the strikes of today to the general mass action which sweeps the bourgeois institutions out of existence. It does not scorn the strike because its declared objects are entirely of immediate concern. Nor does it ask that the strike shall proceed on demands made upon the government itself before it can be of interest to the Communist Party, as does the minority declaration. The life of the Communist movement is the changing character of these mass struggles under imperialistic pressure, and the work of the Communist Party is to enter into these struggles at every stage to develop out of them the consciousness of the class struggle in its ultimate aspects; to develop out of them also the technique of working class social control, as in the assumption of civic functions by the strike committees of Seattle, Winnipeg, Belfast….

Aside from the delegation from Michigan, the Convention elections are no doubt the best indication of the dominant personalities in the new party. One delegate from Detroit would unquestionably have won a place on the Executive Committee for his services in the campaign for the organization of the new party, Dennis E. Batt. For the rest it is not likely that participation in the elections would have changed the outcome.

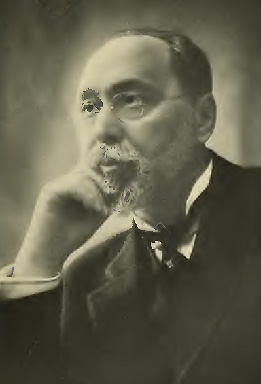

Louis C. Fraina was chosen International Secretary, with I.E. Ferguson as alternate. Fraina’s contribution to the Left Wing movement by his writings in The Class Struggle and The Revolutionary Age gives him a unique position in the development of revolutionary Socialist theory in conformity with American conditions and party circumstances. Comrade Fraina was also elected to the Central Executive Committee, and was named without opposition as Editor of the party publications.

C.E. Ruthenberg of Cleveland was chosen for the important post of National Secretary. Comrade Ruthenberg has a record of service in the Socialist Party which has made him a national figure in the Socialist movement for many years. Already elected by a very large vote as International Delegate and Executive Committeeman of the old party, Ruthenberg now takes these offices in the Communist Party.

The other International Delegates are Nicholas I. Hourwich, editor of Novy Mir; Alexander Stoklitsky, Translator-Secretary of the Russian Federation; and I.E. Ferguson, Secretary of the National Left Wing Council and now Associate Editor of the Communist Party publications. Comrade Hourwich has long been recognized as one of the ablest exponents of Communism in America, and has behind him a long record of intimate association with the work of the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democracy. Comrade Stoklitsky has an easy claim to the most important organizational contribution to the Left Wing movement. It was Comrade Stoklitsky who welded the Russian-speaking Federations into a working unit for the transformation of the Socialist movement in this country, and who did much to bring this solid unit of membership into teamwork with the English-speaking Left Wingers. Comrades Hourwich and Ferguson were elected also to the Central Executive Committee.

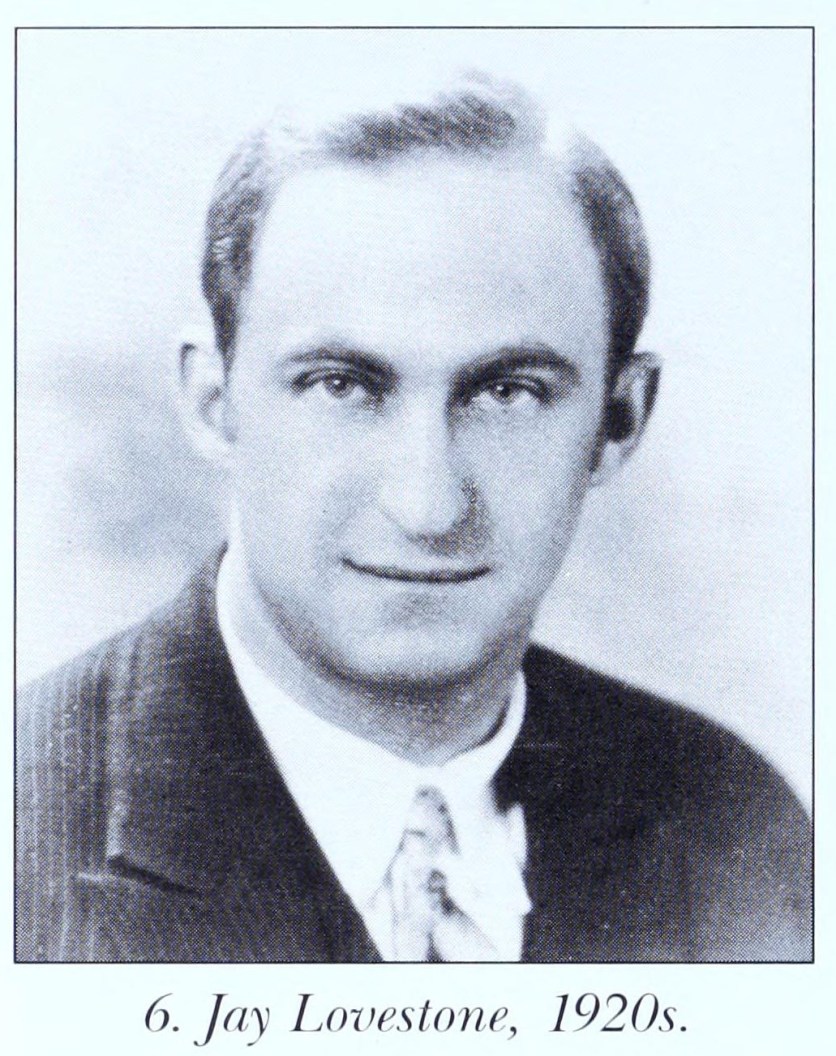

The alternates as International Delegates are Comrades Elbaum, Bittelman, Ballam, and Lovestone. Elbaum is editor of the Polish Federation daily news- paper in Detroit, and Bittelman, as already mentioned, of the Jewish Federation paper in New York. Ballam, member of the National Left Wing Council, is editor of the New England Worker, official organ of the Communist Party of Massachusetts. Jay Lovestone, of New York, one of the youngest of this Convention of young men, proved himself one of the most aggressive and ablest. All of these four were elected also to the Central Executive Committee.

The other delegates elected to the Executive Committee are Comrades Schwartz, Cohen, Tyverovsky, Petras, Karosses, Dirba, Wicks. Schwartz, of Boston, is of the Lettish Federation; Tyverovsky, of New York, is Executive Secretary of the Russian Federation; Petras, of Chicago, is of the Hungarian Federation; Karosses, of Philadelphia, is of the Lithuanian Federation. Maximilian Cohen, of New York, has served as member of the National Left Wing Council and played a very important part in the Left Wing movement as Secretary of the Left Wing Section of New York. Dirba is State Secretary of the Socialist Party in Minnesota, and Wicks one of the newly elected members of the Socialist Party NEC, stood highest on the ballot as Socialist Party delegate from Oregon.

The Executive Council consists of Comrades Ruthenberg, Fraina, Ferguson, Schwartz, Karosses, Dirba, and Wicks.

In view of the argument that has been made about Federation “control,” it is noteworthy that the Executive Council has two Federation members against five non-Federationists, while the entire Executive Committee has a majority of non-Federationists.

Five alternates were chosen for the Executive Committee: Comrades Stokes, Loonin, Georgian, Bixby, and Kravsevitch.

On account of ineligibility to the Executive Committee the names of some of the Translator-Secretaries do not appear in this list, though they were among the outstanding figures of the Convention, notably Joseph Stilson, the Lithuanian Secretary, George Selakovich, South Slavic Federation, and Joseph Kowalsky, Polish Translator-Secretary.

One resolution of special interest was adopted by the Convention: that the propaganda attitude of the Communist Party shall be, when necessary, to explain religion as a social phenomenon and to explain the church as an institution in the light of the materialistic conception of history. It is evident from the refusal to consider religious affiliations as a bar to membership that the Convention meant to draw a sharp distinction between the “propaganda attitude of the party” and censorship of individual religious opinion. This resolution, taken out of the Michigan minority program, puts the Communist Party on record against the evasion of the important subject of religion and the church which has heretofore been the policy of the organized socialist movement in this country. But it does not go to the other extreme of putting an afirmative burden upon the party to carry on a rationalistic campaign, as would be the case with a membership qualification against religious affiliation; it places our attitude squarely upon the social and political aspects of religion.

There are many features of the other committee reports which call for particular notice. There are many other respects in which this Convention stands out from all prior Socialist gatherings in America. For one thing, the fact that the Federation delegates were largely Slavic emphasized the close union between the organization of the Communist Party here and the parent organization which came into being at Moscow in March of this year — the Communist International. It was the Russian expression of Marxism which pre-dominated this Convention, the Marxism of Lenin, and the party traditions of the Bolsheviki.

One delegate after another expressed amazement at the lessons thus brought before him. Many years of most valuable experience were compacted into one week; and there is no question that the students ran the teachers a merry pace.

The Communist Convention and the Communist Party mean the beginning of a disciplined revolutionary working-class movement in America.

Emulating the Bolsheviks who changed the name of their party in 1918 to the Communist Party, there were up to a dozen papers in the US named ‘The Communist’ in the splintered landscape of the US Left as it responded to World War One and the Russian Revolution. This ‘The Communist’ began in September 1919 combining Louis Fraina’s New York-based ‘Revolutionary Age’ with the Detroit-Chicago based ‘The Communist’ edited by future Proletarian Party leader Dennis Batt. The new ‘The Communist’ became the official organ of the first Communist Party of America with Louis Fraina placed as editor. The publication was forced underground in the post-War reaction and its editorial offices moved from Chicago to New York City. In May, 1920 CE Ruthenberg became editor before splitting briefly to edit his own ‘The Communist’. This ‘The Communist’ ended in the spring of 1921 at the time of the formation of a new unified CPA and a new ‘The Communist’, again with Ruthenberg as editor.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/thecommunist/index3.htm