‘The Pecan Slaves of Texas’ by Felipe Ybarra from New Masses. Vol. 8 No. 1. July, 1932.

Maurice Torres, father of four American-born children, a pecan cracker by trade, works from 1 A.M. till 2 P.M. every day in the week but Sunday. That day he only works from 6 A.M. to 9 A.M. In a whole week he cracked seven hundred pounds of nuts at thirty cents per hundred. Saturday afternoon he receives his pay envelope with $1.50: the sixty cents balance has been left in trust with the boss until next week.

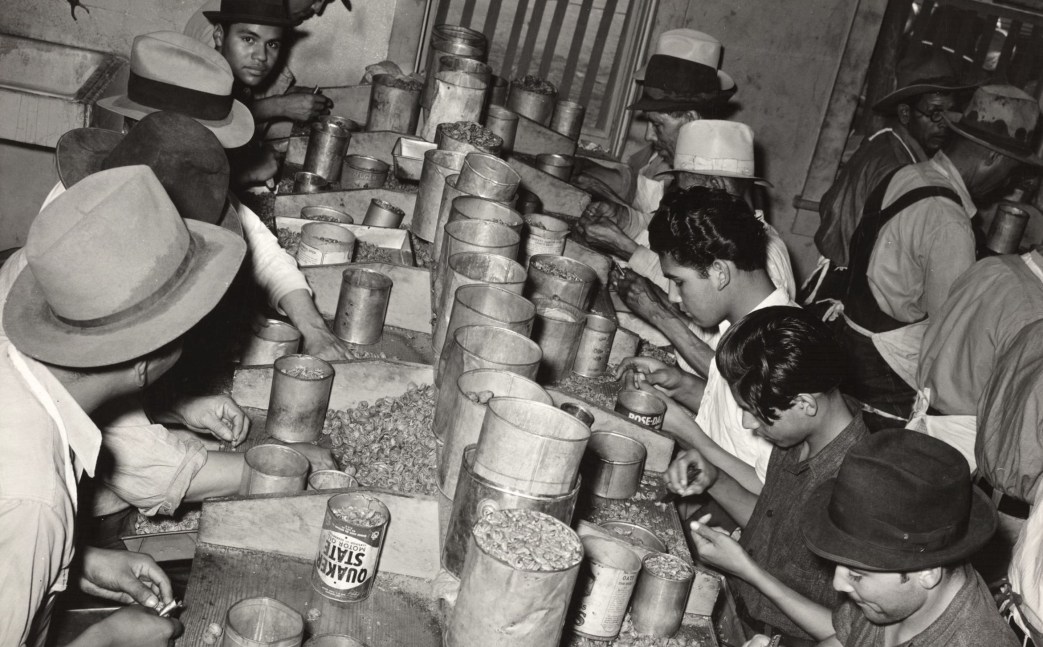

The pecan crackers are considered the aristocrats of the trade, for it is the hardest and most dangerous work in the industry. I asked him whether all the crackers are making so little.

“Some of them are making still less,” was his answer. But if one is fast and experienced and works from 1 A.M. till 6 P.M., and if the pecans are large, and there are plenty to crack, a man can crack from 1500 to 1800 pounds per week, so under very good circumstances a good cracker can make $3.75 a week. But this combination of number one pecans, and plenty of them, happens very seldom; usually the pecans are number three which are very small.

There are about one hundred fifty or more hell holes called pecan factories, scattered all over San Antonio in the Mexican neighborhoods among the Mexican workers. You can find them in every other block, operated by ambitious greedy foxy tricky Mexican businessmen, who are really nothing but imitations of the Americans of that class. Wages hardly keep body and soul together, but there is a little trouble about hours. We have a law in our great state that you can’t work a woman longer than nine hours. Though you can pay her as little as you wish. As it does not pay the big fellows to get in trouble with the law, they give the work to a Mexican sub-contractor, and both of them are satisfied — the big boss at getting the work done cheaper, and the Mexican contractor at paying the workers exactly half the price of a big factory for from 12 to 18 hours labor a day.

Several years ago they paid the shellers twelve cents for halves and ten cents for pieces. Today most of the cockroaches are paying two cents for halves and one cent for pieces. A smart Mexican worker was right when he told me the other day with a smile on his face that, if it keeps up this way, the workers will soon have to pay the bosses for the privilege of working and being squeezed out like a lemon. The fastest, most experienced girl can shell about ten pounds a day, of which six pounds will be halves, and four pounds pieces, so that at very best all she can make in a day is sixteen cents.

But not all the girls are experts. Very few of them can work fast for the simple reason that they eat such poor food and all of one kind. All the average girl can shell is three to six pounds a day: I am leaving to your imagination how much she makes a week.

I am enclosing the pay envelopes of the Chavez sisters. Maria Chavez, number eleven, received $1.07 for a whole week; Tomassa Chavez, number thirty, $1.11 for a week. Maria received only seven cents for a day’s work. Both are young American-born girls. You can easily get a young girl to be good to you here for the price of a cheap pair of stockings, or a good young woman to live with you as common law wife for the price of a square meal a day.

Tomassa Macias, a young smart American-born girl, works in a pecan factory as a Umpiadora (to clean the nuts you must be fast and have very good eyes) five days a week, from six in the morning till seven at night, with only a half hour for lunch and one day in the week from six to six. Wages $3.00 a week. I asked her why she doesn’t quit the job? “Father is out of work, the children are little, I must, must work to help save them.”

Margaritta Flores is a worker forty-nine years old, but looks not a day younger than seventy-five. A proud father of four American-born children of four to fifteen years. An ex-miner with references from several bosses, stating that he has been a good dependable, honest, satisfied slave. With his wife and two of his boys, twelve and fifteen, whom he took out from school to help him make a living, he works six days a week from 6 A.M. to 6 P.M. shelling pecans. Working all week, all four of them shelled 109 pounds at three cents a pound. Saturday the proud

father received the family’s pay envelope with $3.27. Out of this he must pay rent for a shack, buy provisions for the six of them, pay insurance, pay the collector from whom he bought something on the installment plan, buy tobacco for him and his wife, support the Catholic church, and save up a few dollars for a rainy day.

I ask him how does he manage to get along on those few miserable cents? He notices that I am surprised, and thinks that I pity him, feels himself insulted, humiliated, ashamed, gets haughty and answers angrily, “Don’t think that we always made so little. Not long ago all of us made as much as five dollars a week. That was pretty good money. But now the pecans are small, very small, times are hard, competition is big, the boss is greedy and smart, takes advantage of all the workers and cuts, cuts deep the price of the work. The most all four of us can shell in a day is 14 to 18 pounds at three cents a pound.” I dare to ask him again, how can he be satisfied with so little? Hasn’t he got a little ambition? And does he not expect a little joy out of life?

He answers, “Everything is from God. God is big, God knows what He is doing. We can’t and shouldn’t question God. He makes us to suffer for our sins. Those who are suffering here will enjoy life in heaven.”

I feel that I am getting hypnotized. I pity him and his fate and his God and I respect his ignorance which is not his fault. Yet I feel I despise him, this victim of religion, and I hate, hate our cruel and insane system, and its organized Catholic church that makes grown-up people idiots, and good honest workers willing and satisfied slaves. But I feel, too, that it is my duty to help, to tell, to teach, to explain, to show, to prove to him how he and his children are being abused, mistreated, robbed of their health, and sense.

He gets friendly with me, gets a little confidence in me, introduces me to his wife. She invites me inside their shack, a room 10 by 12 with three windows, though none of them has curtains of any kind, only the front window is covered up with a piece of wrapping paper. Two thin rusty iron beds, one has a cheap old broken spring, the other boards instead. Neither has any mattresses, sheets, pillows, or quilts of any kind, only rags. No chairs, no table, no carpets, no linoleum. On one of the walls, three enlarged family pictures, cheap imitation work, cheap frames, an old German clock, a few old rags on one of the walls that used to be coats or pants — and the most prominent corner of the room dedicated to the Mexican Catholic saints. I ask him whether he is a Roman Catholic? He is surprised at my question, and answers, “Si, Senor! Si, Senor! Look over there. See how many saints we have got.” I step over to the shelf which takes up one-third of the space in the room, and there are the Virgen de Guadelupe, Senor San Antonio, Santo Nino de Atocha, Perpetuo Socorro, Virgen de Dolores, and some more saints of which neither one of us knows the names.

He shows me a hole that he and his wife call a kitchen, a wood stove in one corner, a pile of wood in the other, a bare homemade table in another. On the table a kerosene lamp, and all the kitchen utensils they have got and use.

He and his wife explain to me how they exist on the $3.27 they make a week: one dollar a week rent for the shack, one dollar for provisions for the week for all six of them, fifty cents to the collector, twenty-five cents for wood for the week, twenty-five cents for the limosna, Sunday in the church. Anything left over is for kerosene, tortillas, clothes, and milk for the two smaller children.

“My credit is good,” he tells me independently. “If I or my wife are in need or short of anything in the middle of the week, the corner grocery store extends me credit of as much as a dollar with confidence.”

As I go out of the shack I can’t forget their faces. I feel guilty, dizzy, cranky, miserable — all the shame of our cruel insane shameful capitalist system, of which I am a little cog myself. And I feel I must promise myself that my knowledge, education, (as little as I have got), ambition, thoughts, health, freedom, even my life does not belong to my family, but to all misfortunate, abused, ignorant victims of capitalism and its religion.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1932/v08n01-jul-1932-New-Masses.pdf