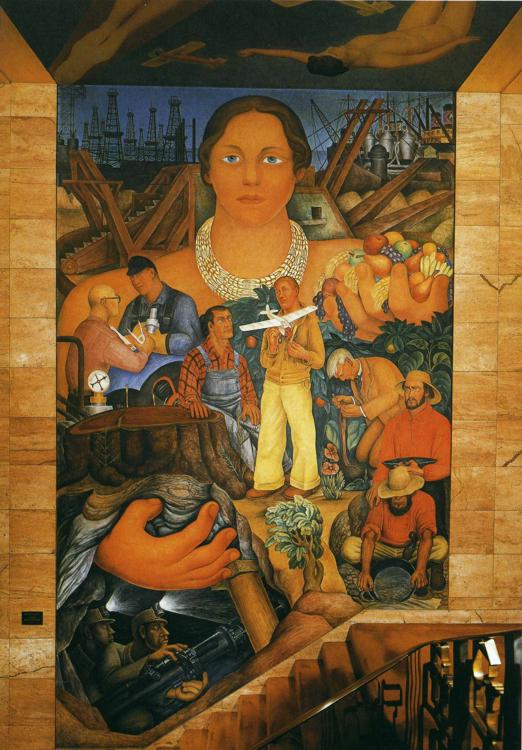

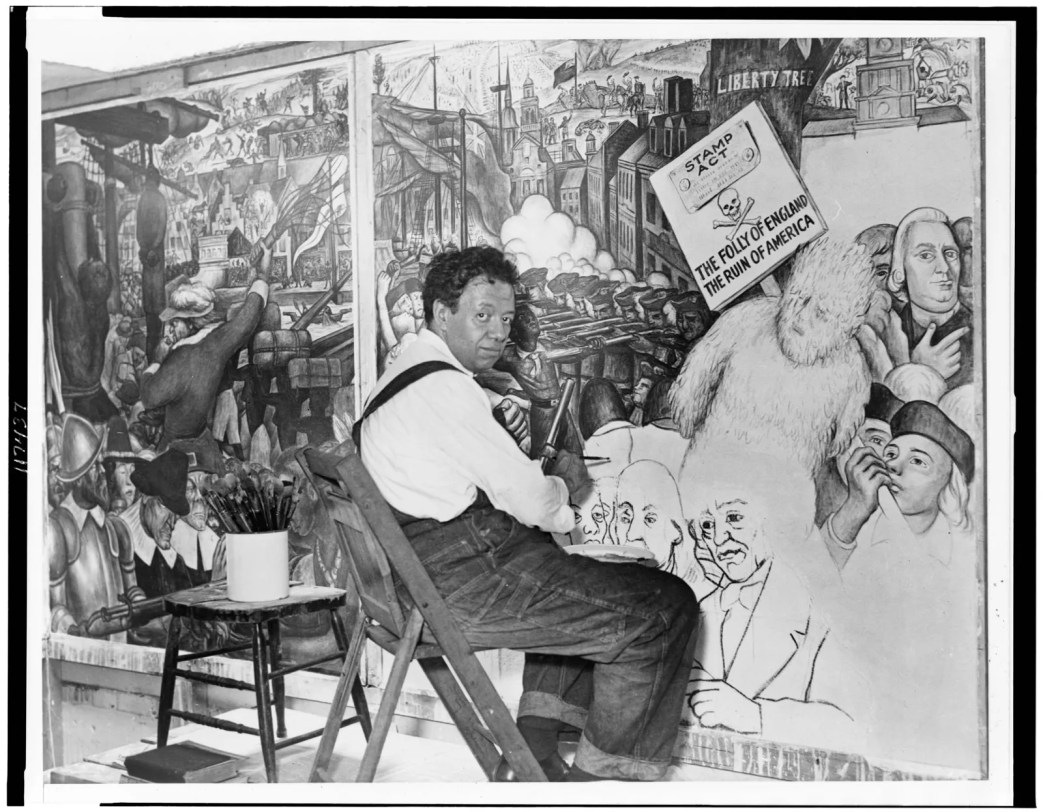

Rivera wrote this fervent essay for V.F. Cavlerton’s ‘Modern Quarterly,’ a journal of Marxist criticism, in conjunction with a major and extremely successful Rivera retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (PDF of original program here) and remains an important statement on the role of revolutionary art. For much of the first half of the 1930s Diego Rivera lived and worked in the United States. Among the notable pieces during his stay were the ‘Allegory of California’ at the Pacific Stock Exchange, ‘The Making of a Fresco Showing the Building of a City’ at the San Francisco Art Institute, the a massive, multi-paneled ‘Detroit Industry’ at the Institute of Arts, and the doomed ‘Man at the Crossroads’ in New York’s Rockefeller Center razed in 1934.

‘The Revolutionary Spirit in Modern Art’ by Diego Rivera from Modern Quarterly. Vol. 6 No. 3. Fall, 1932.

ART is a social creation. It manifests a division in accordance with the division of social classes. There is a bourgeois art, there is a revolutionary art, there is a peasant art, but there is not, properly speaking, a proletarian art. The proletariat produces art of struggle but no class can produce a class art until it has reached the highest point of its development. The bourgeoisie reached its zenith in the French Revolution and thereafter created art expressive of itself. When the proletariat in its turn really begins to produce its art, it will be after the proletarian dictatorship has fulfilled its mission, has liquidated all class differences and produced a classless society. The art of the future, therefore, will not be proletarian but Communist. During the course of its development, however, and even after it has come into power, the proletariat must not refuse to use the best technical devices of bourgeois art, just as it uses bourgeois technical equipment in the form of cannon, machine guns, and steam turbines.

Such artists as Daumier and Courbet in the nineteenth century were able to reveal their revolutionary spirit in spite of their bourgeois environment. Honore Daumier was a forthright fighter, expressing in his pictures the revolutionary movement of the 19th century, the movement that produced the Communist Manifesto. Daumier was revolutionary both in expression and in ideological content. In order to say what he wanted to say, he developed a new technique. When he was not actually painting as anecdote of revolutionary character, but was merely drawing a woman carrying clothes or a man seated at a table eating, he was nevertheless creating art of a definitely revolutionary character. Daumier developed a drastic technique identified with revolutionary feeling, so that his form, his method, his technique always expressed that feeling. For example, if we take his famous laundress, we find that he has painted her with neither the eye of a literary man nor with that of a photographer. Daumier saw his laundress through class-conscious eyes. He was aware of her connection with life and labor. In the vibration of his lines, in the quantity and quality of color which he projected upon the canvas, we see a creation directly contrary and opposed to the creations of bourgeois conservative art. The position of each object, the effects of light in the picture, all such things express the personality in its complete connection with its surroundings and with life. The laundress is not only a laundress leaving the riverbank, burdened with her load of clothes and dragging a child behind her; she is, at one and the same time, the expression of the weariness of labor and the tragedy of proletarian motherhood. Thus we see, weighing upon her, the heavy burdens of her position as woman and the heavy burdens of her position as laborer; in the background we discern the houses of Paris, both aristocratic and bourgeois. In a fraction of a second, a person, unless he be blind, can see in the figure of this laundress not only a figure but a whole connection with life and labor and the times in which she lives. In other paintings of Daumier are depicted scenes of the actual class struggle, but whether he is portraying the class struggle or not, in both types of painting we can regard him as a revolutionary artist. He is so not because he was of proletarian extraction, for he was not. He did not come from a factory, he was not of a working class family; his origin was bourgeois, he worked for the bourgeois papers, selling his drawings to them. Nevertheless, he was able to create art which was an efficacious weapon in the revolutionary struggle, just as Marx and Engels despite their bourgeois origin were able to write works which serve as basis for the development of the proletarian revolutionary movement.

The important fact to note is that the man who is truly a thinker, or the painter who is truly an artist, cannot, at a given historical moment, take any but a position in accordance with the revolutionary development of his own time. The social struggle is the richest, the most intense and the most plastic subject which an artist can choose. Therefore, one who is born to be an artist can certainly not be insensible to such developments. When I say born to be an artist, l refer to the constitution or make-up of his eyes, of his nervous system, of his sensibility, and of his brains. The artist is a direct product of life. He is an apparatus born to be the receptor, the condenser, the transmitter and the reflector of the aspirations, the desires, and the hopes of his age. At times, the artist serves to condense and transmit the desires of millions of proletarians; at times, he serves as the condenser and transmitter only for small strata of the intellectuals or small layers of the bourgeoisie. We can establish it as a basic fact that the importance of an artist can be measured directly by the size of the multitudes whose aspirations and whose life he serves to condense and translate.

The typical theory of 19th century bourgeois esthetic criticism, namely “art for art’s sake,” is an indirect affirmation of the fact which I have just stressed. According to this theory, the best art is the so-called “art for art’s sake,” or “pure” art. One of its characteristics is that it can be appreciated only by a very limited number of superior persons. It is implied thereby that only those few superior persons are capable of appreciating that art; and since it is a superior function it necessarily implies the fact that there are very few superior persons in society. This artistic theory which pretends to be apolitical has really an enormous political content-the implication of the superiority of the few. Further, this theory serves to discredit the use of art as a revolutionary weapon and serves to affirm that all art which has a theme, a social content, is bad art. It serves, moreover, to limit the possessors of art, to make art into a kind of stock exchange commodity manufactured by the artist, bought and sold on the stock exchange, subject to the speculative rise and fall which any commercialized thing is subject to in stock exchange manipulations. At the same time, this theory creates a legend which envelops art, the legend of its intangible, sacrosanct, and mysterious character which makes art aloof and inaccessible to the masses. European painting throughout the 19th century had this general aspect. The revolutionary painters are to be regarded as heroic exceptions. Since art is a product that nourishes human beings, it is subject to the action of the law of supply and demand just as is any other product necessary to life. In the 19th century the proletariat was in no position to make an effective economic demand for art products. The demand was all on the part of the bourgeoisie. It can be only as a striking and heroic exception, therefore, that art of a revolutionary character can be produced under the circumstances of bourgeois demand.

At present art has a very definite and important role to play in the class struggle. It is definitely useful to the proletariat. There is great need for artistic expression of the revolutionary movement. Art has the advantage of speaking a language that can easily be understood by the workers and peasants of all lands. A Chinese peasant or worker can understand a revolutionary painting much more readily and easily than he can understand a book written in English. He needs no translator. That is precisely the advantage of revolutionary art. A revolutionary painting takes far less time and it says far more than a lecture does.

Since the proletariat has need of art, it is necessary that the proletariat take possession of art to serve as a weapon in the class struggle. To take possession or control of art, it is necessary that the proletariat carry on the struggle on two fronts. On one front is a struggle against the production of bourgeois arts- and when I say struggle I mean struggle in every sense- and on the other is a struggle to develop the ability of the proletariat to produce its own art. It is necessary for the proletariat to learn to make use of beauty in order to live better. It ought to develop its sensibilities, and learn to enjoy and make use of the works of art which the bourgeoisie, because of special advantages of training, has produced. Nor should the proletariat wait for some painter of good will or good intentions to come to them from the bourgeoisie; it is time that the proletariat develop artists from their own midst. By the collaboration of the artists who have come out of the proletariat and those who sympathize and are in alliance with the proletariat, there should be created an art which is definitely and, in every way, superior to the art which is produced by the artists of the bourgeoisie.

Such a task is the program of the Soviet Union today. Before the Russian Revolution, many artists from Russia, including those who were leading figures in the Russian revolutionary movement, had long discussions in their exile in Paris over the question as to what should be the true nature of revolutionary art. I had the opportunity to take part, at various times, in those discussions. The best theorizers in those discussions, misunderstanding the doctrine of Marx which they sought to apply, came to the conclusion that revolutionary art ought to take the best art that the bourgeoisie had developed and bring that art directly to the revolutionary masses. Each of the artists was certain that his own type of art was the best that the bourgeoisie had produced. Those artists who had the greatest development of collective spirit, those who had grouped themselves around various “isms,” such as Cubism and Futurism, were convinced that their particular group was creating the art which would become the art of the revolutionary proletariat as soon as they were able to bring that particular “ism,” that particular school of art, to the proletariat. I ventured to disagree with them, maintaining that while it was necessary to utilize the innumerable technical developments which bourgeois art had developed, we had to use them in the same way that the Soviet Union utilizes the machine technique that the bourgeoisie has developed. The Soviet Union takes the best technical development and machinery of the bourgeoisie and adapts it to the needs and special conditions of the new proletarian regime; in art, I contended, we must also use the most advanced technical achievements of bourgeois art but must adapt them to the needs of the proletariat so as to create an art which, by its clarity, by its accessibility, and by its relation to the new order, should be adapted to the needs of the proletarian revolution and the proletarian regime. But I could not insist upon their accepting my opinion, for, up to the time of that discussion, I had not created anything which in any way differed fundamentally from the type of art that my comrades were creating. I had arrived at my conclusion in the following manner: I had seen the failure and defeat of the Mexican revolution of 1919, a defeat which I became convinced was the result of a lack of theoretical understanding on the part of the Mexican proletariat and peasantry. I left Mexico when the counter-revolution was developing under Madeiro, deciding to go to Europe to get the theoretical understanding and the technical development in art which I thought was to be found there.

The Russian comrades returned from Paris to Russia immediately after the Revolution, taking with them the most advanced technique in painting which they had learned in Paris. They did their best and created works of considerable beauty, utilizing all the technique which they had learned. They carried on a truly heroic struggle to make that art accessible to the Russian masses. They worked under conditions of famine, the strain of revolution and counter revolution, and all the material and economic difficulties imaginable, yet they failed completely in their attempts to persuade the masses to accept Cubism, or Futurism, or Constructivism as the art of the proletariat. Extended discussions, of the whole problem arose in Russia. Those discussions and the confusion resulting from the rejection of modern art gave an opportunity to the bad painters to take advantage of the situation. The academic painters, the worst painters who had survived from the old regime in Russia, soon provided competition on a grand scale. Pictures inspired by the new tendencies of the most advanced European schools were exhibited side by side with the works of the worst academic schools of Russia. Unfortunately, those that won the applause of the public were not the new painters and the new European schools but the old and bad academic painters. Strangely enough, it seems to me, it was not the modernistic painters but the masses of the Russian people who were correct in the controversy. Their vote showed not that they considered the academic painters as the painters of the proletariat; but that the art of the proletariat must not be a hermetic art, an art inaccessible except to those who have developed and undergone an elaborate esthetic preparation. The art of the proletariat has to be an art that is warm and clear and strong. It was not that the proletariat of Russia was telling these artists; “You are too modern for us.” What it said was: “You are not modern enough to be artists of the proletarian revolution.” The revolution and its theory, dialectical materialism, have no use for art of the ivory tower variety. They have need of an art which is as full of content at the proletarian revolution itself, as clear and forthright as the theory of the proletarian revolution.

In Russia there exists the art of the people, namely peasant art. It is an art rooted in the soil. In its colors, its materials, and its force it is perfectly adapted to the environment out of which it is born. It represents the production of art with the simplest resources and in the least costly form. For these reasons it will be of great utility to the proletariat in developing its own art. The better Russian painters working directly after the Revolution should have recognized this and then built upon it, for the proletariat, so closely akin to the peasant in many ways, would have been able to understand this art. Instead of this the academic artists, intrinsically reactionary, were able to get control of the situation. Reaction in art is not merely a matter of theme. A painter who conserves and uses the worst technique of bourgeois art is a reactionary artist, even though he may use this technique to paint such a subject as the death of Lenin or the red flag on the barricades. In the same fashion, an engineer engaged in the construction of a dam with the purpose of irrigating Russian soil would be reactionary if he were to utilize the bourgeois procedures of the beginning of the 19th century. In that case he would be reactionary, he would be guilty of a crime against the Soviet Union, even though he were trying to construct a dam for the purpose of irrigation.

The Russian theatre was safe from the bankruptcy which Russian painting suffered. It was in direct contact with the masses, and, therefore, has developed into the best theatre that the world knows today. Bit by bit, the theatre has attracted to it painters, sculptors, and, of course, actors, dancers, musicians. Everyone in the Soviet Union who has any talent for art is being attracted to the theatre as a fusion of arts. In proportion with the progress made in the construction of socialism in the Soviet Union, artists are turning more and more to the theatre for expression and the masses are coming closer and closer to the theatre as an “expression of their life.” The result is that the other arts are languishing and Russia is producing less and less of the type of art which, in the rest of Europe, serves as shares on the Stock Exchange.

Mural art is the most significant art for the proletariat. In Russia mural paintings are projected on the walls of clubs, of union headquarters, and even on the walls of the factories. But Russian workers came to me and declared that in their houses they would prefer having landscapes and still-lives, which would bring them a feeling of restfulness. But the easel picture is an object of luxury, quite beyond the means of the proletariat. I told my fellow artists in Russia that they should sell their paintings to the workers at low prices, give them to them if necessary. After all, the government was supplying the colors, the canvass, and the material necessary for painting, so that artists could have sold their work at low prices. The majority, however, preferred to wait for the annual purchase of paintings made by the Commissariat of Education when pictures were, and still are, bought for five hundred rubles each.

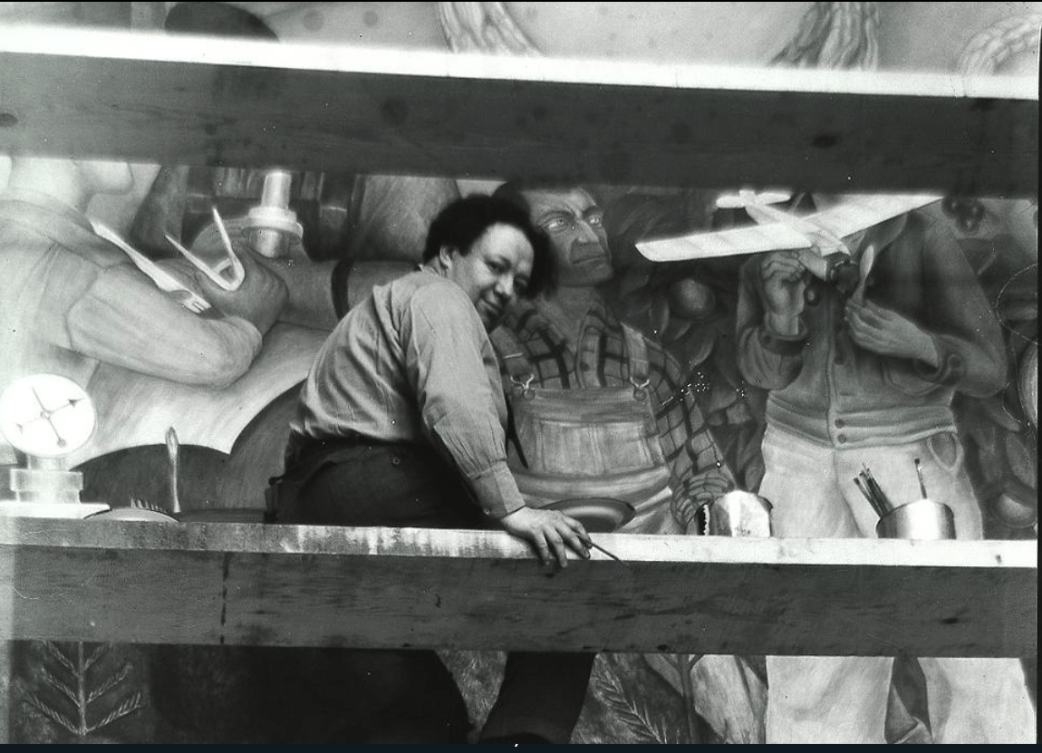

I did not feel that I had the right to insist upon my viewpoint until I had created something of the type of art I was talking about. Therefore, in 1921, instead of going to Russia where I had been invited by the Commissariat of Education, I went to Mexico to attempt to create some of the art that I had been exalting. This effort of mine had in it something of the flavor of adventure because, in Mexico, there was a proletarian regime. There was in power at that time, a fraction of the bourgeoisie that had need of demagogy as a weapon in maintaining itself in power. It gave us walls, and we Mexican artists painted subjects of a revolutionary character. We painted, in fact, what we pleased, even including a certain number of paintings which were certainly communistic in character. Our task was first to develop and remake mural paintings in the direction of the needs of the proletariat, and, second to note the effect that such mural painting might have upon the proletarians and peasants in Mexico, so that we could judge whether that form of painting would be an effective instrument of the proletariat in power. But let me note also another fact. In Mexico there existed an old tradition, a popular art tradition much older and much more splendid than even the peasant art of Russia. This art is of a truly magnificent character. The colonial rulers of Mexico, like those of the United States, had despised that ancient art tradition which existed there, but they failed to destroy it completely. With this art as background, I became the first revolutionary painter in Mexico. The paintings served to attract many young painters, painters who had not yet developed sufficient social consciousness. We formed a painters’ union and began to cover the walls of buildings in Mexico with revolutionary art. At the same time we revolutionized the methods of teaching drawing and art to children, with the result that the children of Mexico began producing artistic works in the course of their elementary school development.

As a result of these things, when, in 1927, I was again invited to go to Moscow. I felt that I could go as we Mexicans had some experience which might help Soviet Russia. I ought to remark at this point that among the painters in Mexico, thanks to the development of the new methods of teaching painting in the schools of the workers, there developed various working-class painters of great merit, among them Maximo Patcheco, whom I consider the best mural painter m Mexico.

The experience which I tried to offer to the Russian painters was brought to Russia at a moment of intense controversy. In spite of the fact that it was a poor time for artistic discussion and development, Corrolla, the comrade who was formerly in charge of “Agitprop” work, organized a group, “October,” to discuss and make use of the Mexican artistic experiments. I was engaged to paint by the metallurgical workers who wanted me to paint the walls in their club, the “Dynamo Club” on the Leningrad Chaussee. Soon, however, owing to differences, not of an aesthetic but of a political character, I was instructed to return to Mexico to take part in the “election campaign beginning there.” A few months after my return to Mexico I was expelled from the Party. Since then, I have remained in a position which is characteristically Mexican, namely that of the guerilla fighter. I could not receive my munitions from the Party because my Party had expelled me; neither could I acquire them through my personal funds because I haven’t any. I took them and will continue to take them, as the guerilla fighter must, from the enemy. Therefore, I take the munitions from the hands of the bourgeoisie. My munitions are the walls, the colors, and the money necessary to feed myself so that I may continue to work. On the walls of the bourgeoisie, painting cannot always have as fighting an aspect as it could on the walls, let us say, of a revolutionary school. The guerilla fighter sometimes can derail a train, sometimes blow up a bridge, but sometimes he can only cut a few telegraph wires. Each time he does what he can. Whether important or insignificant, his action is always within the revolutionary line. The guerilla fighter is always ready, at the time of amnesty, to return to the ranks and become a simple soldier like everybody else. It was in the quality of a guerilla fighter then that I came to the United States.

As to the development of art among the American workers, I have already seen paintings in the John Reed Club, which are undoubtedly of revolutionary character and at the same time aesthetically superior to the overwhelming majority of paintings which can be found in the art galleries of the dealers in paintings.

I saw yesterday the work of a lad-formerly a painter of abstract art-who has just completed a series of paintings on the life and death of Sacco and Vanzetti which are as moving as anything of the kind I have ever seen. The Sacco and Vanzetti paintings are technically within the school of modernistic painting, but they possess the necessary qualities, accessibility, and power, to make them important to the proletariat. Here and there I have seen drawings and lithographs of high quality, all by young and unknown artists. I am convinced that within the United States there is the ability to produce a high development of revolutionary art, advancing upward, from below. The bourgeoisie at times will be persuaded to buy great pictures in spite of their revolutionary character. In the galleries of the richest men there are pictures by Daumier. But these sources of demand are most precarious. The proletariat must learn to depend upon itself, however limited its resources may be. Rembrandt died a poor man in the wealthy bourgeois Holland of his day. In spite of his innumerable paintings there was scarcely a crust of bread in his house when he was found dead. His painting knew how to offend the wealthy Dutch bourgeoisie.

In Rembrandt I find a basis of profound humanity and to a certain extent of protest. This is much more definite in the case of Cezanne. It is sufficient to point out that Cezanne used the workers and peasants of France as the heroes and central figures of his paintings. It is impossible today to look at a French peasant without seeing a painting of Cezanne.

Bourgeois art will cease to develop when the bourgeoisie as a class is destroyed. Great paintings, however, will not cease to give aesthetic pleasure though they have no political meaning for the proletariat. One can enjoy the Crucifixtion by Mantegna and be moved by it aesthetically without being a Christian. It is my personal opinion that there is in Soviet Russia today too great a veneration of the past. To me, art is always alive and vital, as it was in the Middle Ages when a new mural was painted every time a new political or social event required one. Because I conceive of art as a living and not a dead thing, I see the profound necessity for a revolution in questions of culture, even in the Soviet Union.

Of the recent movements in art, the most significant to the revolutionary movement is that of Super-Realism. Many of its adherents are members of the Communist Party. Some of their recent work is perfectly accessible to the masses. Their maxim is “Super-Realism at the service of the Revolution.” Technically they represent the development of the best technique of the bourgeoisie. In ideology, however, they are not fully Communist. And no painting can reach its highest development or be truly revolutionary unless it be truly Communist.

And now we come to the question of propaganda. All painters have been propagandists or else they have not been painters. Giotto was a propagandist of the spirit of Christian charity, the weapon of the Franciscan monks of his time against feudal oppression. Breughel was a propagandist of the struggle of the Dutch artisan petty bourgeoisie against feudal oppression. Every artist who has been worth anything in art has been such a propagandist. The familiar accusation that propaganda ruins art finds its source in bourgeois prejudice. Naturally enough the bourgeoisie does not want art employed for the sake of revolution. It does not want ideals in art because its own ideals cannot any longer serve as artistic inspiration. It does not want feelings because its own feelings cannot any longer serve as artistic inspiration. Art and thought and feeling must be hostile to the bourgeoisie today. Every strong artist has a head and a heart. Every strong artist has been a propagandist. I want to be a propagandist and I want to be nothing else. I want to be a propagandist of Communism and I want to be it in all that I can think, in all that I can speak, in all that I can write, and in all that I can paint. I want to use my art as a weapon.

For the real development on a grand scale of revolutionary art in America, it is necessary to have a situation where all unite in a single party of the proletariat and are in a position to take over the public buildings, the public resources, and the wealth of the country. Only then can there develop a genuine revolutionary art. The fact that the bourgeoisie is in a state of degeneration and depends for its art on the art of Europe indicates that there cannot be a development of genuine American art, except in so far as the proletariat is able to create it. In order to be good art, art in this country must be revolutionary art, art of the proletariat, or it will not be good art at all.

Modern Quarterly began in 1923 by V. F. Calverton. Calverton, born George Goetz (1900–1940), a radical writer, literary critic and publisher. Based in Baltimore, Modern Quarterly was an unaligned socialist discussion magazine, and dominated by its editor. Calverton’s interest in and support for Black liberation opened the pages of MQ to a host of the most important Black writers and debates of the 1920s and 30s, enough to make it an important historic US left journal. In addition, MQ covered sexual topics rarely openly discussed as well as the arts and literature, and had considerable attention from left intellectuals in the 1920s and early 1930s. From 1933 until Calverton’s early death from alcoholism in 1940 Modern Quarterly continued as The Modern Monthly. Increasingly involved in bitter polemics with the Communist Party-aligned writers, Modern Monthly became more overtly ‘Anti-Stalinist’ in the mid-1930s Calverton, very much an iconoclast and often accused of dilettantism, also opposed entry into World War Two which put him and his journal at odds with much of left and progressive thinking of the later 1930s, further leading to the journal’s isolation.