Hebert Biel continues his thoroughly researched, Marxist analysis of class conflicts in the South, still often overlooked, in the decade before the Civil War. This second part covers the conflict between ‘poor whites’ and the Southern oligarchy with sections on Slaveholder vs. Non-Slaveholder, Southern Anti-Slavery Sentiment, The Ideology of the Slavocracy, and the Slaveholders’ Rebellion. Part one here.

‘Class Conflicts in the South, 1850-1860, Part II: Non-Slaveholder vs. Slaveholder’’ by Herbert Biel from The Communist. Vol. 18 No. 3. March, 1939.

NON-SLAVEHOLDER VS. SLAVEHOLDER

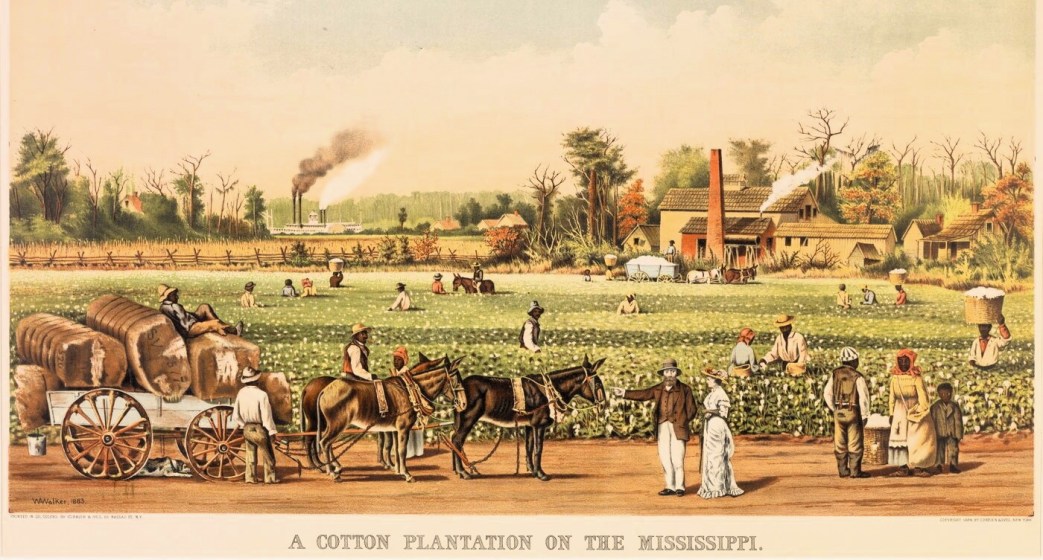

IN 1860 there were over eight million white people in the slaveholding states. Of these but 384,000 were slaveholders among whom were 77,000 owning but one Negro. Less than 200,000 whites throughout the South owned as many as ten slaves—a minimum necessity for a plantation. And it is to be noted that, while, in 1850 one out of every three whites was connected, directly or indirectly, with slaveholding, in 1860 only one out of every four had any direct or indirect connection with slaveholding. Moreover, in certain areas, particularly Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri and Virginia, the proportion of slaves to the total population noticeably fell.1

These facts are at the root of the maturing class conflict—slaveholder versus non-slaveholder—which was the outstanding internal political factor in the South in the decade prior to Secession. It is, of course, true generally that, “…the real central theme of Southern history seems to have been the maintenance of the planter class in control.”2 But never did that class face greater danger than in the decade preceding the Civil War.

Let us briefly examine the challenges to Bourbon rule in a few Southern states.

In Virginia,3 at the insistence of the generally free-labor, non-plantation West united with artisans and mechanics of Eastern cities, a constitutional convention was held in 1850-51. On two great questions the Bourbons lost; representation was considerably equalized by the overwhelming vote of 75,748 to 11,063, and the suffrage was extended to include all free white males above twenty-one years of age. The history of Virginia for the next eight years revolves around an eversharpening struggle between the slaveholders and non-slaveholders. The power of the latter was illustrated in the election of Letcher over Goggin in 1859 as Governor. In that campaign slavocratic rule was the issue and the Eastern slaveholders’ papers appreciated the meaning of Letcher’s victory. Thus, for example, the Richmond Whig of June 7, 1859, declared:

“Letcher owes his election to the tremendous majority he received in the Northwest Free Soil counties, and in these counties to his anti-slavery record.”

In North Carolina, too, there was an “evident tendency of the non-slaveholding West to unite with the nonslaveholding classes of the East,”4 and this unifying tendency brought important victories. In 1850, for the first time in fifteen years, a Democratic candidate, David S. Reid, captured the governorship, and he won because he urged universal manhood suffrage in elections to the state’s senate (ownership of fifty acres of land was then required in order to vote for a senator) as well as to the lower house. Slaveholders’ opposition prevented the enactment of such a law for several years but the people never wearied in their efforts and, finally, free suffrage was ratified,5 August, 1857, by a vote of 50,007 to 19,379.

A valiant struggle was also carried on for a more equitable tax system— ad valorem taxation—in North Carolina.6 A few figures will illustrate the situation. Slaves, from the ages of 12 to 50 only, were taxed 534 cents per hundred dollars of their value. But land was taxed 20 cents per hundred dollars, and workers’ tools and implements were taxed one dollar per hundred dollars value. Thus, in 1850, slave property worth $203,000,000 paid but $118,330 tax, while land worth $98,000,000 paid over $190,000 in taxes. A Raleigh worker asked in 1860: “Is it no grievance to tax the wages of the laboring man, and not tax the income of their (sic) employer?”

The leader in the fight for equalized taxation was Moses A. Bledsoe, a state senator from Wake County. In 1858 he united with the recently formed Raleigh Workingmen’s Association to fight this issue through. He was promptly read out of the Democratic Party, but, in 1860, ran as an independent and was elected. The issue split the Democratic Party in North Carolina and seriously threatened the political strength of the slavocracy. Professor W. K. Boyd has remarked,7 “one cannot but see in the ad valorem campaign the beginning of a revolt against slavery as a political and economic influence…”

Similar struggles occurred in South Carolina.8 The bitter congressional campaign of October, 1851, in which secessionists were beaten, again by a united front of farmers and urban workers, by a vote of 25,045 to 17,710, was “marked by denunciations hurled by freemen of the back country against the barons of the low country.” The next year a National Democratic Party was launched, led by men like J. L. Orr (later Speaker of the National House), B. F. Perry, and J. J. Evans.9 Their program cut at the heart of the slavocracy. Let South Carolina abandon its isolationism, let it permit the popular election of the President and Governor (both selected by the state legislature), let it end property qualifications for members of its legislature, let it equalize the vicious system of apportionment (which made the slaveholding East dominant), let it establish colleges in the Western part of the state (as it had in the Eastern), and let it provide ample free schools. And, finally, let it enter upon a program of diversified industry. None of these reforms was carried, except partial advance along educational lines, but the threat was considerable and unmistakable.10

SOUTHERN ANTI-SLAVERY SENTIMENT

Overt anti-slavery sentiment was not lacking in the South. One evidence of this has been presented in the material showing that whites were often implicated with slaves in their conspiracies.

The New Orleans Courier of October 25, 1850, devoted an editorial to castigating native anti-slavery men, who, it declared, were numerous. Some even thought that two-thirds of the people of New Orleans would be willing to vote for emancipation. An anonymous letter writer said that this was so because there were so many workers in the city who owned no slaves. Earlier that same year a leading Democratic paper of Mississippi, the Free Trader, had declared that “the evil, the wrong of slavery, is admitted by every enlightened man in the Union.”11 Professor A. C. Cole has also noted “certain indications which point to a hostility on the part of some of the non-slaveholding Democrats outside of the black belt to the institution of slavery itself.”12

Competent contemporary witnesses testify to such a feeling, and it certainly was very widespread in Western Kentucky, Eastern Tennessee, Western North Carolina, Western Virginia, and Maryland, Delaware and Missouri.13

THE IDEOLOGY OF THE SLAVOCRACY

In order to evaluate properly the effect of the misbehavior of the exploited, Negro and white, upon the mind of the slavocracy, it is instructive to investigate its ideology. Formally, the Democratic Party was derived from Jefferson, but by the 1820’s the crux of that democrat’s philosophy, i.e., man’s right and competence to govern himself, was being scrapped in the South, for one of an authoritarian nature; there has always been slavery, there will always be slavery, and there should always be slavery. And, said the slavocrats, our form of slavery is especially delightful for two reasons: first, our slaves are Negroes, and while slavery is good in itself, the fact that we enslave an “inferior” people makes our slavery particularly good; and, secondly, since ours is not a wage slavery, but chattel slavery, we have no class problem.

Thus Bishop Elliot would declare at Savannah, February 23, 1862, that following the American Revolution,

“…we declared war against all authority…The reason of man was exalted to an impious degree and in the face not only of experience, but of the revealed word of God, all men were declared equal, and man was pronounced capable of self-government…Two greater falsehoods could not have been announced, because the one struck at the whole constitution of civil society as it had ever existed, and because the other denied the fall and corruption of man.”14

And thus, too, a Georgia paper, the Muskogee Herald, of 1856, might exclaim:

“Free society! we sicken at the name. What is it but a conglomeration of greasy mechanics, filthy operatives, small-fisted farmers, and moon-struck theorists?”15

But here were the mechanics and artisans and farmers, Negro and white, of the South, doggedly agitating and conspiring and dying for the same “moon-struck” ideas—liberty and progress! What to do?

There were two ideas as concerns the Negro: reform slavery16 (legalize marriage, forbid separation of families, allow education); and further repression. The latter, repression, won with hardly a struggle.

The Bourbons were too, keenly aware of the dangerous trend among the non-slaveholding whites. Propaganda flooded the South to the effect that the interests of slaveholders and non-slaveholders were really the same. Said the press, “…arraying the non-slaveholder against the slaveholder…is all wrong…The fact that one man owns slaves does not in the least injure the man who owns none.”17

Slavocracy’s leading publicist, J. D. B. DeBow, issued a pamphlet on The Interest in Slavery of the Southern Non-Slaveholder (Charleston, 1860), and the politicians played the Bourbons’ trump card, the non-slaveholders “may have no pecuniary interest in slavery, but they have a social interest at stake that is worth more to them than all the wealth of the Indies.”18

But, asked the Bourbons and their apologists, why then does it so often happen that whites aid slaves in their plots? Why, they asked, do some agitate against slavery and distribute “vicious works” like that by North Carolina’s “renegade son,” Helper’s Impending Crisis? Why do they struggle for political and economic reforms similar to those of Northern “moonstruck” theorists?

Merchants and capitalists, Northern merchants and capitalists, are sympathetic, they reasoned, “but the mechanics, most of them, are pests to society, dangerous among the slave population, and ever ready to form combinations against the interest of even the slaveholder, against the laws of the country, and against the peace of the Commonwealth.”19 And “slaves are constantly associating with low white people, who are not slave owners. Such people are dangerous to a community, and should be made to leave our city.”20

A visitor to Georgia, in December, 1859, felt that “the slaveholder seems to watch more carefully to keep the poor white man in subjection than he does to guard the slaves.”21 The North Carolinian Calvin Wiley warned in 1860:

“…that there was as much danger from the prejudice existing between the rich and poor as between master and slave [and felt that] all attempts…to widen the breach between classes of citizens are just as dangerous as efforts to excite slaves to insurrection.”22

In 1850 a South Carolinian, J. H. Taylor, had written that:

“…the great mass of our poor white population begin to understand that they have rights, and that they, too, are entitled to some of the sympathy which falls upon the suffering…It is this great upheaving of our masses we have to fear, so far as our institutions are concerned.”23

And in February, 1861, another South Carolinian, observing the growth of a white laboring class and its opposition to the slavocratic philosophy declared:

“It is to be feared that even in this State, the purest in its slave condition, democracy may gain a foothold, and that here also the contest for existence may be waged between them,”24

One month later, March 27, 1861, the Raleigh, N. C., Register observing the increasing class bitterness in its own state actually “expressed a fear of civil war within the state.”25

What, then, is the situation? The national supremacy of the slavocracy is gone. And its local power is threatened by both its victims—the slaves and the non-slaveholding whites— separately and, with alarming frequency, jointly. The South Carolina Senator James Hammond had warned, in 1847, that slavery’s “only hope” was to keep “the actual slaveholders not only predominant, but paramount within its circles.”26

THE SLAVEHOLDERS’ REBELLION

This “only hope” appeared to be slipping away, if it were not already gone, by 1860. Desperation replaced hope, and desperation—the conviction that there was everything to gain and nothing to lose—led to the slaveholders’ rebellion.

And it was their rebellion. As one of them, a South Carolinian, A. P. Aldrich, wrote November 25, 1860:

“I do not believe the common people understand it; but whoever waited for the common people when a great movement was to be made? We must make the move and force them to follow. That is the way of all great revolutions and all great achievements.”27

One month later a wealthy North Carolinian, Kenneth Rayner, confided to Judge Thomas Ruffin that he “was mortified to find…that the people who did not own slaves were swearing that they would not lift a finger to protect rich men’s negroes. You may depend on it…that this feeling prevails to an extent, you do not imagine.”28

Just a few days before the start of actual warfare Virginia’s arch-secessionist, Edmund Ruffin, admitted to his diary, April 2, 1861, that it was:

“…communicated privately by members of each delegation (to the Confederate Constitutional Convention) that it was supposed people of every State except S. Ca. was indisposed to the disruption of the Union and that if the question of reconstruction of the former Union was referred to the popular vote, that there was probability of its being approved.”29

The Raleigh, N. C., Standard, whose editor, W. W. Holden, had been read out of the Democratic Party because of his non-slaveholding proclivities, saw very clearly the result of a rebel. lion whose base was merely several thousand distraught slaveholders. Its editorial of February 5, 1861, warned that:

“The Negroes will know, too, that the war is waged on their account. They will become restless and turbulent…Strong governments will be established and bear heavily on the masses. The masses will at length rise up and destroy everything in their way…”

CONCLUSION

This article has attempted to present a new emphasis upon a factor hitherto insufficiently appreciated in appraising the causes that drove the slaveholding class to desperation and counter-revolution in 1861. This desperation was not merely due to the growing might of a free-labor industrial bourgeoisie, combined, via investments and transportation ties, with the free West, and to that group’s capture of national power in 1860. Another important factor, becoming more and more potent as the slavocracy was being weakened by capitalism in the North, was the sharpening class struggle within the South itself from 1850 to 1860. This struggle manifested itself in serious slave disaffection, in frequent cooperation between poor whites and Negro slaves, and in the rapid maturing of the political consciousness of the non-slaveholding whites.

And, taking another step, he who seeks to understand the reasons for the ultimate collapse of the Confederacy will find them not only in the military might of the North, but, in an essential respect, in the highly unpopular character of that government. The Southern masses opposed the Bourbon regime and it was this opposition, of the poor whites and of the Negro slaves, that contributed largely to its downfall.

REFERENCES

- A. C. Cole, The Irrepressible Conflict, New York, 1934, p. 34; L. C. Gray, History of Agriculture in the Southern United States, Washington, 1933, II, p. 656.

- W. Hesseltine, Journal of Negro History, 1936, XXI, p. 14

3.See two studies by J. Chandler, Representation in Virginia, Baltimore, 1896, pp. 63-69; History of Suffrage in Virginia, Baltimore, 1901, pp. 49-54; - C. H. Ambler, American Historical Review, 1910, XV, pp. 769-76. 4H. M. Wagstaff, State Rights … in North Carolina, Baltimore, 1906, p. 111.

- Memoirs of W. W. Holden, Durham, p. 5; C. C. Norton, The Democratic Party in Ante-Bellum N.C., Chapel Hill, 1930, Pp. 173.

- W. K. Boyd, Trinity College Historical Society Publications, 1905, V, p. 31; Wagstaff, op. cit.; p. 110; Norton, op. cit.; pp. 199-204.

- Annual Report of the American Historical Association, 1910, p. 174.

- In 1849 a white man was tried for incendiarism in Spartanburg, S.C., and one of the pieces of evidence against him was a pamphlet by “Brutus” called An Address to South Carolinians urging poor whites to demand more political power. See H. Henry, Police Control of the Slaves in South Carolina, Emory, 1914, p. 159; D. D. Wallace, History of South Carolina, New York, 1934, III, p. 130.

- Laura A. White in South Atlantic Quarterly, 1929, XXVIII, pp. 370-89; White, Robert B. Rhett, New York, 1931, p. 123 and Chapter VIII; Wallace, op. cit., HI, pp. 129-38.

- For accounts of similar contests elsewhere see, T. Abernethy, From Frontier to Plantation in Tennessee, Chapel Hill, 1932, p. 216; C. Ramsdell in Studies in Southern History and Politics, New York, 1914, p. 66; W. E. Smith, The F. P. Blair Family in Politics, New York, 1933, I, pp. 292, 300, 303, 337, 374, 400, 416, 440.

- J. B. Ranck, Albert G. Brown, York, 1937, p. 65.

- Cole, The Whig Party in the South, Washington, 1913, p. 72; it is true that an anti-Negro feeling was often mixed with the anti-slavocratic feeling of the poor whites. Nevertheless, the latter feeling was present. For example, Hinton R. Helper was anathema to the slavocracy notwithstanding the fact that he was possessed of a vicious antiNegro prejudice.

- Olmsted, Back Country, p. 180; Stirling, Letters, p. 326; J. Aughey, The Iron Furnace, Philadelphia, 1863, pp. 39, 228; see G. G. Johnson, Ante-Bellum North Carolina, p.577.

- W. S. Jenkins, Pro-Slavery Thought in Old South, Chapel Hill, 1935, p. 240.

- Following title page of A. Cole’s Irrepressible Conflict.

- See Liberator, February 1, 1856; R. Taylor. North Carolina’ Historical Review, 1925, II, p. 33.

- Charlotte, June 12, 1860.

- Senator A. G. Brown of Mississippi quoted by Ranck, op cit., p. 147; see also W. Bean in North Carolina Historical Review, 1935, XIII, p. 115.

- Olmsted, Seaboard, Il, pp. 149-50, quoting a South Carolina paper.

- Mobile, Mercury, quoted in New York Daily Tribune, January 8, 1861.

- J. S. Abbott, South and North, New York, 1860, p. 150.

- G. G. Johnson, op. cit., p. 78.

- DeBow’s Review, January, 1850, quoted by P. Tower, Slavery Unmasked, Rochester, 1856, p. 348, emphasis in original.

- Charleston, Mercury, February 13, 1861, in Political Science Quarterly, 1907, XXII, p. 428; see D. Dumond, The Secession Movement, New York, 193!, p. 117.

- H. M. Wagstaff, op. cit., p. 145.

- D. D. Wallace, op. cit., II, p. 130.

- L. A. White, Rhett, p. 177; see also Marx to Engels, July 5, 1861, in their Civil War in U. S., pp. 228-30, where the votes in the secession conventions are analyzed.

- C. C. Norton, op. cit., p. 204.

- White, Rhett, p. 202.

There are a number of journals with this name in the history of the movement. This ‘Communist’ was the main theoretical journal of the Communist Party from 1927 until 1944. Its origins lie with the folding of The Liberator, Soviet Russia Pictorial, and Labor Herald together into Workers Monthly as the new unified Communist Party’s official cultural and discussion magazine in November, 1924. Workers Monthly became The Communist in March, 1927 and was also published monthly. The Communist contains the most thorough archive of the Communist Party’s positions and thinking during its run. The New Masses became the main cultural vehicle for the CP and the Communist, though it began with with more vibrancy and discussion, became increasingly an organ of Comintern and CP program. Over its run the tagline went from “A Theoretical Magazine for the Discussion of Revolutionary Problems” to “A Magazine of the Theory and Practice of Marxism-Leninism” to “A Marxist Magazine Devoted to Advancement of Democratic Thought and Action.” The aesthetic of the journal also changed dramatically over its years. Editors included Earl Browder, Alex Bittelman, Max Bedacht, and Bertram D. Wolfe.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v18n03-mar-1939-The-Communist-OCR.pdf