The story of the fight against toxic Benzol poisoning in the rubber industry and the larger problem of ‘industrial diseases,’ the beginning of the pioneering Workers’ Health Bureau project of the Painters’ Union to address the well being of their members. Harriet Silverman was the Bureau’s director, whose leadership also included Grace Burnham and Charlotte Todes.

‘Organizing Trade Unions to Combat Disease’ by Harriet Silverman from Labor Age. Vol. 11 No. 8. September, 1922.

A New Workers Health Program—the Painters the First to Adopt It

WHAT would you give to add a number of years to your life, and make these years freer from pain and disease? Is it worth $3 a year? If your union could do that thing for you at that amount, would you want it done? Ask these questions of any union man, and you can be pretty sure of the reply. Six locals of the Brotherhood of Painters, New York City, have answered them by installing their own Health Department—to fight disease by preventing it.

These locals have taken up what is in reality a new working class health program. They believe that the barn should be locked before the horse is stolen—not afterward. They have seen their members “burnt out at 40”—victims of lead poisoning, a burden upon themselves and every one about them. They realize that industrial disease crushes men as effectively as the attacks of employers, and that both should be met and put to rout.

The trade unions of America, in dealing with their problems of health, have generally followed a different course. They have provided they have been unaware of how to handle this problem, and have followed the only course open to them—to pay benefits after disease has | made its inroads. This not only means that the worker is seriously injured through a false sense of security; it also blinds him to the fact that health is an industrial and class problem deserving the same place in his union program as hours, wages and working conditions.

Labor men and labor officials can only look around them to see that the troubles which afflict their fellow workers largely grow out of their trade. The bodies of workmen have stamped upon them the character of their labor. Look upon any group of workers and you see bodies, misshapen by loads never intended for sick and death benefits and sanatoria for the treatment of disease, usually in the advanced stages. These measures are certainly necessary in lessening the hardships of illness or in hastening recovery. It will be pretty readily seen, however, that they are inadequate even for this purpose, and are merely negative measures. They do not prevent disease; they do not cope effectively with the problem that the worker faces. Neither measure recognizes the fact that most of the worker’s diseases are caused by his work and must be stopped at the source. Health is a Class Problem

The medical profession is largely to blame for this shortsightedness. It is only within recent years, particularly since the introduction of workmen’s compensation laws, that medical science has taken any real steps to prevent diseases arising from industrial causes. The general policy of the unions up to date shows that human backs, muscles or nerves; grey ashen faces, the results of work in industry deprived of sunlight; hearts, stomachs and lungs destroyed by fumes, foul air, dusts and poisons. Bodies are after all only so much of the raw material which goes into the production of goods.

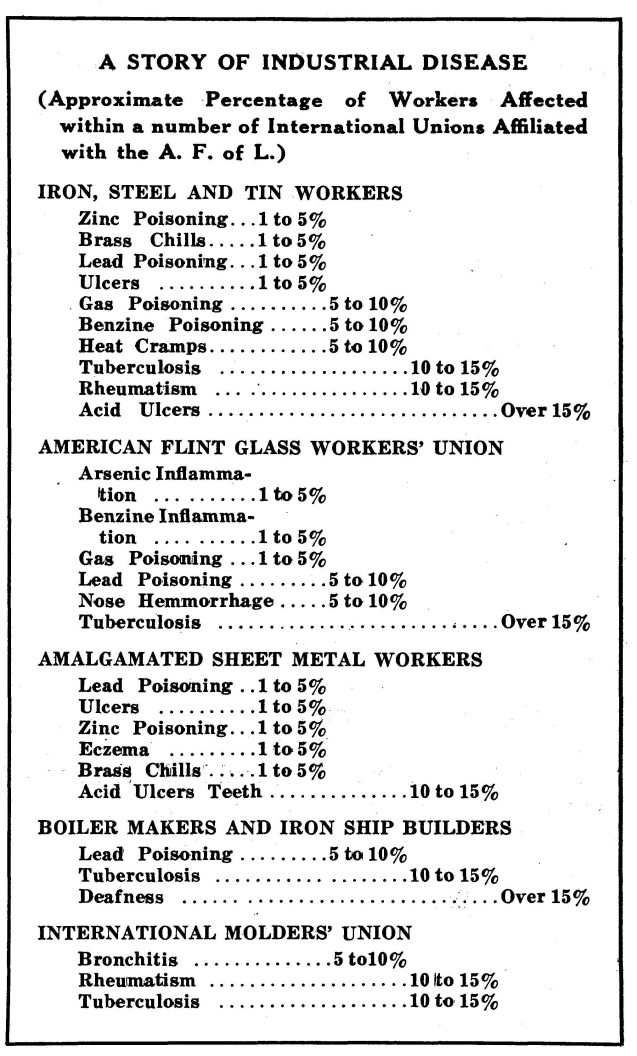

The story of industrial disease can be well learned from the box on page 11. The figures are taken from a chart, drawn up on the basis of physical examinations made of workers in the state of Ohio. Forty-four trades, affiliated with the American Federation of Labor, were represented in this study. Tuberculosis was found to be the most common trade disease. Lead poisoning, which most people identify with the painting trade, comes next. As a matter of fact, workers in at least 15 trades are exposed to this poison:

Blacksmiths, Boilermakers, Stove Mounters, Foundry Workers, Iron, Steel and Tin Workers, Machinists, Sheet Metal Workers, Potters, Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers, Flint Glass Workers, Leather Workers, Printers and Allied Crafts, Painters and Allied Crafts, Furniture Workers, Piano and Organ Workers.

Trade unions, on the whole, are not awake to what this chart means. At the same time, Capital, always on the watch for increasing its profits, introduces new devices and materials without regard to the health of the workers. When this occurs, why should not the unions be equipped to demand that certain conditions be brought about that will mean life to the workers instead of death?

The Menace of Benzol

Take, for example, the death-dealing Benzol, which has lately come into the rubber industry. It menaces the lives of increasing numbers of workers engaged in making tires, footwear or hose. What is this Benzol and how can its bad effects be overcome? It is a by-product of coal tar and is valuable for quick drying paints and for dry cleaning. It must evaporate in the air before the process in which it is used is completed. Workers breathe the air bearing its deadly fumes. loss of consciousness may occur when there are from 2 to 3 parts of Benzol to 10,000 of air. Dr. Alice Hamilton, one of the two foremost Industrial Hygienists in this country, writing in the Journal of the American Medical Association on “The Growing Menace of Benzol Poisoning,” Says:

“If a man is susceptible to benzene (Benzol) it takes only a small quantity to poison or even kill him. In a case described by a German physician, the kettle containing the Benzol had been empty for twenty-two hours, was washed out twice with steam and three times with cold water, and then allowed to stand all night filled with cold water. As one of the workmen went in, a strong current of air was blown in through a pipe. In spite of all these precautions, he was overcome and fell to the bottom of the tank. Several of his fellow workmen tried to get him out, but all grew dizzy and confused, and had to give it up. Finally, an engineer in a diver’s helmet succeeded in rescuing him, and he was revived; but one of the workingmen who had helped in the rescue died within ten minutes of inhaling the fumes.”

In Ohio the death of a young woman was recently traced to the presence of Benzol in glue used for trimming hats, showing that Benzol enters the body through the skin as well as by breathing in the fumes.

How can Benzol poisoning be prevented? Experience has proven that even powerful exhausts placed close to the fumes to carry off the poison, are useless. For close work all precautions are futile, particularly in such processes as varnishing automobiles or removing shellac. What is the solution? Enforcement of ‘existing factory health laws, or introduction of new laws? In other words, dependence upon public health agencies? If Labor intends seriously to attack the problem, this policy will not do.

Labor Cannot Depend on “Public’’ Agencies

The sustained propaganda and lobbying necessary for the passage of some weak law limiting the use of dangerous devices or materials shows how little public bodies are interested in Industrial Disease.

City, State and National Public Health Authorities can exercise protection on the job by enforcing present laws, or by introducing new laws for safeguarding machinery, tools, materials and work places. Within certain limits this is being done. However, with each change in political office there is a change of policy. The moment a trade requires drastic, swift action to introduce safe substitutes for dangerous chemicals, acids, paints or machinery, the question immediately arises, can we afford to antagonize the employers? Invariably the decision is against the workers. Even if public occupational disease clinics were generally established for the examination of workers regularly, they would not only be pitifully inadequate but would suffer from the defects of all public welfare institutions—interminable red tape—indifferent, superficial treatment— indirect contact—with the workers. There would be lacking that intimate and personal supervision which gets results.

It’s the Union’s Job

The problem of industrial disease is fundamentally a problem dealing with working conditions. The trade union is the agency which Labor employs to improve its working conditions. The realization that no organization but that of the workers themselves can combat exploitation in any of its forms is the premise upon which trade unions have been organized.

Who better than the trade unions of America can take up this new function, a constructive plan of action to control the causes of disease at their source—the job? Labor needs a parallel for the Rockefeller Foundation—AN INSTITUTE OF HEALTH RESEARCH. Labor possesses no laboratory for conducting experiments to discover the true nature of diseases, has no system of Health Education to teach workers to understand their bodies, and lacks the necessary machinery for providing regular physical examinations to safeguard bodies against disease.

Lacking these, Labor cannot demand that changes take place in the industry that will make industrial disease a thing of small consequence. That is the best of the real things that will result from the union’s preventive health policy: that the workers will be spurred to take up and enforce “health demands”; to exercise health control of the industry in which they work.

Introducing the Workers’ Health Bureau

Recognizing this condition, the Workers’ Health Bureau was organized in New York City in July, 1921. The Bureau’s function is to study health destroying processes in the trades, analyze harmful materials and develop health plans suited to the needs of the particular group of local unions uniting for the work.

The health program outlined by the Bureau is to be carried out in each Trade Union through the establishment of a Health Department, financed and controlled by the Union membership. The Health Department would offer all members a careful physical examination, with blood and urine tests, mouth examination and cleansing of teeth, also x-ray examinations wherever necessary.

The Bureau operates on a national scale and is supported by yearly affiliation fees of 25 cents a member from locals joining the Bureau. Affiliated trades are entitled to the service of the Bureau in establishing a Health Department, in compiling health statistics for the trade, and in preparing courses of instruction on the care of the body.

In addition to local affiliation, State conferences may join the Bureau by paying $25 a year. Affiliated trades are entitled to representation on the executive council with voice in shaping its policies. In this way it is hoped to build up a health foundation, uniting all the trades in the fight against a common enemy.

During the first year of its existence, the Bureau has secured affiliation from two State conferences and from eleven local unions. It has just organized and set in operation the first Trade Union Health Department in the country for the Prevention of Trade Diseases. The Workers’ Health Bureau supervises the departments which it establishes in order to maintain the proper medical standards. In this the Bureau is assisted by an advisory committee of experts among whom are Dr. Alice Hamilton and Prof. Emery R. Hayhurst.

The Painters’ Program

The Department recently organized is known as The Journeymen Painters and Allied Crafts Health Department. It is located in room 211, at 80 East 11th Street, New York City. The Painters’ Health Department, equipped with its own laboratory and X-ray machine, is open four evenings a week and all day Saturday. The staff consists of a medical director, dentist, nurse, laboratory technician and x-ray operator who is also a physician. Each member of the union receives a careful physical examination with urine analysis, blood tests, mouth examination and cleansing of the teeth. Members suffering from trade diseases, return to the Painters’ Health Department for treatment. Compensation cases are included in the work, but the chief purpose is to PREVENT DISEASE. The kind of examination offered costs from $20 to $25 on the market. By uniting their buying power, the painters have reduced the cost to $3.00 for the first year’s per capita assessment. The Painters’ Health Department challenges all organized workers to strike out for a similar health policy, aiming to destroy the industrial causes of disease.

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v11n08-sept-1922-LA.pdf