Albert Rhys Williams classic first-hand account of his relationship with Lenin from the night of November 7, 1917 where he first saw Lenin speak at the Smolny, through the Brest-Litovsk and the early months of 1918.

‘100 Days With Lenin’ by Albert Rhys Williams from Lenin: The Man and his Work with Raymond Robins and Arthur Ransome. Scott and Seltzer Publishers, New York. 1919.

1. Young Disciples of Lenin

I SAW Lenin first not in the flesh but in the minds and spirits of five young Russian workingmen. They were part of the great tide of exiles flowing back into Petrograd in the summer of 1917.

Americans were drawn to them by their energy, intelligence and their knowledge of English. They soon informed us that they were Bolsheviks. “They certainly don’t look it,” said an American. For a time he would not believe it He had seen in the paper the picture of the Bolsheviks as long-bearded, ignorant, indolent ruffians. And these men were clean-shaven, polite, humorous, amiable and alert. They were not afraid of responsibility, not afraid to die, and most marvellous of all in Russia, not afraid to work. And they were Bolsheviks.

Woskov hailed from New York, where he had been the organizer of the Carpenters’ and Joiners’ Union, Number 1008. Yanishev, a mechanic, the son of a village priest, bore on his body the marks of labor in mines and mills all around the world. Niebut, an artisan, always carried a pack of books and was always enthusiastic over his latest find. Volodarsky, working day and night like a galley slave, said to me a few weeks before he was assassinated, “Oh, what of it! Supposing they do get me! I have had more joy working these last six months than any five men ought to have in all their lives.” Peters, a foreman, who later appeared in the press reports as a bloody” tyrant signing death-warrants until his fingers could no longer hold the pen, was often sighing for his English rose-garden and the poems of Nekrasov.

These men quietly assured us that, in brains and character, Lenin led not only all the Bolsheviks, but everybody else in Russia, in Europe and in all the world.

For us who daily read in the papers of Lenin, the German agent, and daily heard the bourgeoisie outlaw him as a scoundrel, a traitor, and an imbecile, this was indeed strange doctrine. It sounded fantastic and fanatical. But these men were neither fools nor sentimentalists. Knocking about the world had hammered all that out of them. Nor were these men hero-worshippers. The Bolshevik movement was elemental and passionate, but it was scientific, realistic, and uncongenial to hero-worship. Yet here was this quintette of Bolsheviks declaring that there was one Russian, great in integrity and in intelligence, and his name was Nikolai Lenin, at that time an outlaw hunted by the Provisional Government.

The more we saw of these young zealots the more we desired to see the man they acknowledged as their master. Would they take us to his hiding-place?

“Wait a little while,” they would reply, laughing, “then you shall see him.”

Impatiently we waited through the summer and into the fall of 1917, watching the Kerensky Government grow weaker and weaker. On November 7 the Bolsheviks pronounced it dead and at the same time proclaimed Russia to be a Republic of Soviets with Lenin as its Premier.

2. First Impression of Lenin

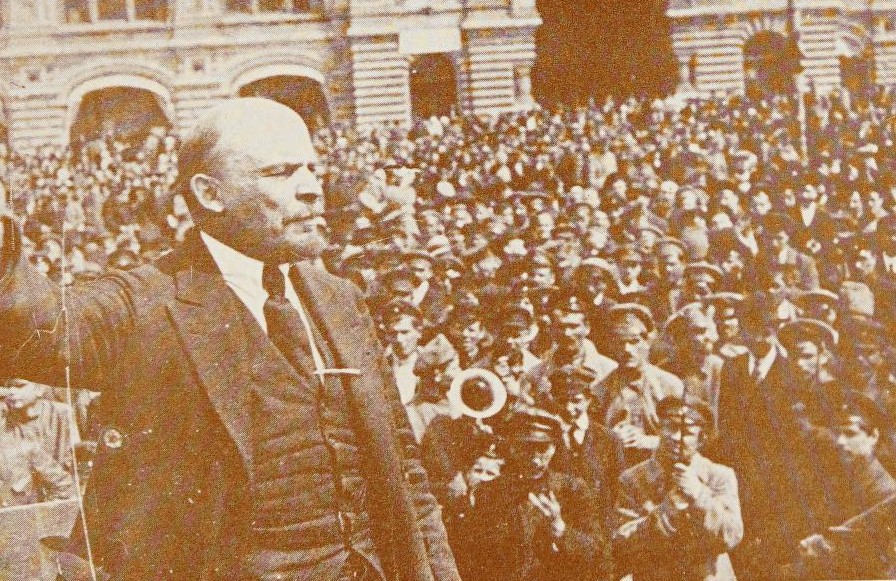

While a tumultuous, singing throng of peasants and soldiers, flushed with the triumph of their revolution, jammed the great hall at Smolny, while the guns of the Aurora were heralding the death of the old order and the birth of the new, Lenin quietly stepped upon the tribunal and the Chairman announced, “Comrade Lenin will now address the Congress.”

We strained to see whether he would meet our image of him, but from our seats at the reporters’ table he was at first invisible. Amidst loud cries, cheers, whistles and stamping of feet he crossed the platform, the demonstration rising to a climax as he stepped upon the speaker’s rostrum, not more than thirty feet away. Now we saw him clearly and our hearts fell.

He was almost the opposite of what we had pictured him. Instead of looming up large and impressive he appeared short and stocky. His beard and hair were rough and unkempt.

After stilling the tornado of applause he said, “Comrades, we shall now take up the formation of the Socialist State.” Then he went into an unimpassioned, matter-of-fact discussion. In his voice there was a harsh, dry note rather than eloquence. Thrusting his thumbs in his vest at the arm-pits, he rocked back and forth on his heels. For an hour we listened, hoping to discern the hidden magnetic qualities which would account for his hold on these free, young, sturdy spirits. But in vain.

We were disappointed. The Bolsheviks by their sweep and daring had captured our imaginations; we expected their leader to do likewise. We wanted the head of this party to come before us, the embodiment of these qualities, an epitome of the whole movement, a sort of super-Bolshevik. Instead of that, there he was, looking like a Menshevik, and a very small one at that.

“If he were spruced up a bit you would take him for a bourgeois mayor or banker of a small French city,” whispered Julius West, the English correspondent.

“Yes, a rather little man for a rather big job,” drawled his companion.

We knew how heavy was the burden that the Bolsheviks had taken up. Would they be able to carry it? At the outset, their leader did not strike us as a strong man.

So much for a first impression. Yet, starting from that first adverse estimate, I found myself six months later in the camp of Woskov, Niebut, Peters, Volodarsky and Yanishev, to whom the first man and statesman of Europe was Nikolai Lenin.

3. Lenin Injects Iron Discipline into the State Life

On November 9th I desired a pass to accompany the Red Guards then streaming out along all roads to fight the Cossacks and the counter-revolutionists. I presented my credentials bearing the signature of Hillquit and Huysmans. I thought they were a very imposing set of credentials. But Lenin didn’t. Quite as if they came from the Union League Club, he handed them back with a laconic, “No.”

This was a trivial incident, but indicative of a new, rigorous attitude now appearing in the councils of the proletarians. Hitherto, to their own destruction, the masses had been indulging their excessive amiability and good nature. Lenin set out for discipline. He knew that only strong, stern action could save the Revolution, menaced by hunger, invasion and reaction. So the Bolsheviks drove their measures through without ruth or hesitation, while their enemies ransacked the arsenals of invective for epithets to assail them. To the bourgeoisie Lenin was the high-handed, ironfisted one. At this period they referred to him not as Premier Lenin, but as “the Tyrant Lenin,” “Lenin the Dictator.” And the Right Socialists said, the old Romanov Tsar, Nicholas II, has given place to the new Tsar, Nikolai Lenin, and in derision shouted, “Long live our new Tsar Nicholas III!”

They seized with joy upon the humorous incident of the peasant. It was the night when the Soviet of Peasants’ Deputies, throwing its support to the new Soviet government, celebrated with a glorified love-feast in the halls of Smolny. The intelligentsia had spoken for the village; there was a demand that the village should speak for itself. An old fellow in peasant’s smock came to the platform. His face showed rosy through his white beard; he had twinkling eyes, and spoke in the village dialect.

“Tovarishchi, how happy I was tonight as we came here with banners flying and music playing. I didn’t come walking on the ground. I came flying through the air. I am one of the dark people, living in a dark village. You gave us the light. But we don’t understand it all, so they sent me here to find out But, Tovarishchi, we are all very happy over the wonderful change. In the old days the chinovniki used to be very hard and beat us, but now they are very polite. In the old days we could only look at the outsides of the palaces, now we can walk right inside them. In the old days we only talked about the Tsar, but they tell us now, Tovarishchi, tomorrow I can shake hands with Tsar Lenin himself. God grant him long life!”

The audience exploded. Astounded at the roars of laughter and applause, the old peasant sat down. But the next day he was presented to Lenin, and later was the peasants’ representative at Brest-Litovsk.

During these chaotic weeks only iron will and iron nerve would suffice. Rigid order and discipline were evident in all departments. One could note the stiffening of the morale of the workingman, a tightening up of the loose parts in the Soviet machinery. Now when the Soviet moved out into action, as for example in the seizure of the banking system, it struck hard and effectively. Lenin knew where to be precipitate in action, but he knew also where to go slow. A delegation of workingmen came to Lenin asking him if he could decree the nationalization of their factory.

“Yes,” said Lenin, picking up a blank form, “it is a very simple thing, my part of it. All I have to do is to take these blanks and fill in the name of your factory in this space here, and then sign my name in this space here, and the name of the commissar here.” The workmen were highly gratified and pronounced it “very good.”

“But before I sign this blank,” resumed Lenin, “I must ask you a few questions. First, do you know where to get the raw materials for your factory?” Reluctantly they admitted they didn’t.

“Do you understand the keeping of accounts,” resumed Lenin, “and have you worked out a method for keeping up production?” The workmen said they were afraid they did not know very much about these minor matters.

“And finally, comrades,” continued Lenin, “may I ask you whether you have found a market in which to sell your products?”

Again they answered, “No.”

“Well, comrades,” said the Premier, “don’t you think you are not ready to take over your factory now? Go back home and work over these matters. You will find it hard; you will make many blunders, but you will learn. Then come back in a few months and we can take up the nationalizing of your factory.”

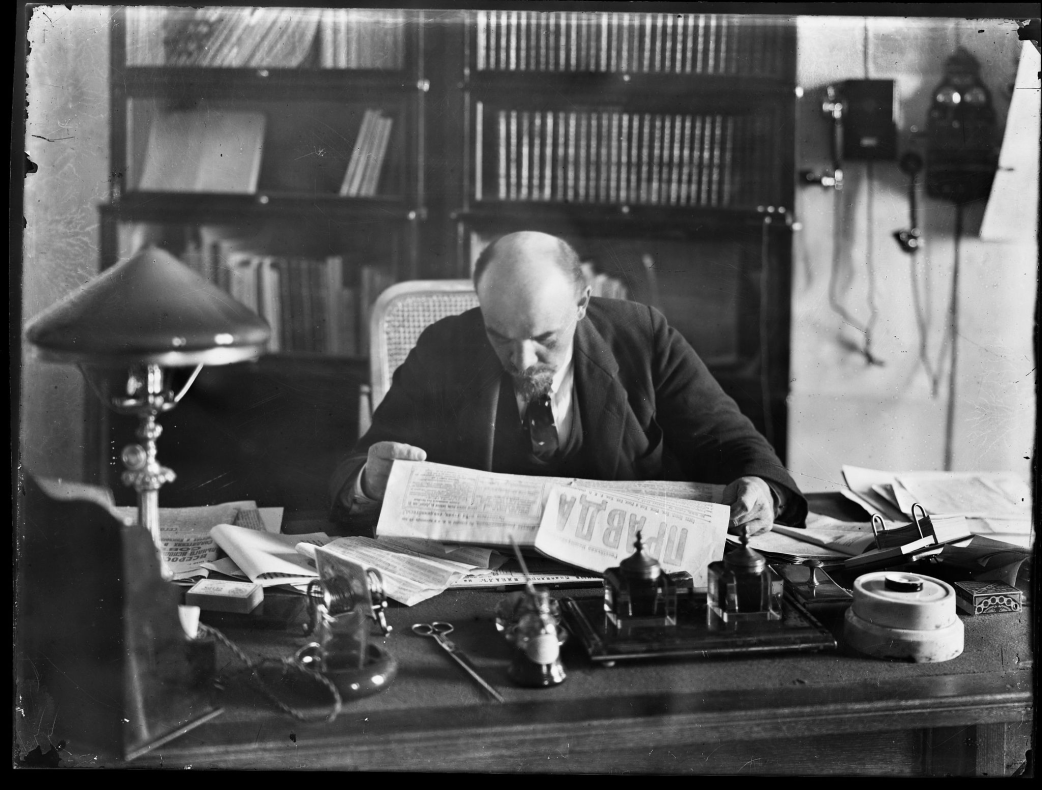

4. Iron Discipline in Lenin’s Personal Life

The same iron that Lenin was injecting into the social life he showed in his individual life. Shchi and borshch, slabs of black bread, tea and porridge made up the fare of the Smolny crowds. It was likewise the usual fare of Lenin, his wife and sister. For twelve and fifteen hours a day the revolutionists stuck to their posts. Eighteen and twenty hours was the regular stint for Lenin. In his own hand he wrote hundreds of letters. Immersed in his work, he was dead to everything, even his own sustenance. Grasping her opportunity when Lenin was engaged in conversation his wife would appear with a glass of tea, saying, “Here, tovarishch, you must not forget to drink this.” Often the tea was sugarless, for Lenin went on the same ration as the rest of the population. The soldiers and messengers slept on iron cots in the big, bare, barrack-like rooms. So did Lenin and his wife. Wearied, they flung themselves down on their rough couches, oftentimes without undressing, ready to rise to any emergency. Lenin did not take upon himself these privations out of any ascetic impulses. He was simply putting into practise the first principle of Communism.

One of these principles was that the pay of any Communist official should be no larger than the pay of an average workingman. It was fixed at a maximum of 600 rubles a month. Later there was an increase. As it is today, the Premier of Russia receives less than $200 a month.

I was in the National Hotel when Lenin took a room on the second floor. The first act of the new Soviet regime was the abolition of the elaborate and expensive menus. The many dishes that comprised a meal were cut down to two. One could have soup and meat or soup and kasha. And that is all that anyone, whether Chief Commissar or kitchenboy, could have, for it is written in the creed of the Communists that “No one shall have cake until everybody has bread.” On some days there was very little even of bread for the people. Still each person got just as much as Lenin. Occasionally there were days without any bread at all. Those days, too, were breadless days for him.

When Lenin was near death in the days following the attempt upon his life, the physicians prescribed some food not obtainable on the regular food-card and which could be bought only in the market from some speculator. In spite of all the entreaties of his friends, he refused to touch anything which was not part of the legitimate ration.

Later when Lenin was convalescing his wife and sister hit upon a scheme for increasing his nutriment. Finding that he kept his bread in a drawer, in his absence they slipped into his room and now and then added a piece to his store. Absorbed in his work, Lenin would reach into the drawer and take a bit, which he ate quite unconscious that it was any addition to the regular ration.

In a letter to the workers of Europe and America, Lenin wrote: “Never have the Russian masses suffered such depths of misery, such pangs of hunger as those to which they are now condemned by the military intervention of the Entente!” But these same sufferings Lenin was enduring along with the masses about whom he writes.

Lenin has been accused of gambling with the life of a great nation, an experimentalist recklessly trying out his communistic formulas upon the sick body of Russia. But he cannot be accused of lack of faith in those formulas. He not only tries them on Russia. He tries them on himself. He is willing to take his own medicine. To pay homage to the doctrines of Communism from a distance is one thing. To endure, as does Lenin, the privations and rigors that the introduction of Communism entails on the spot is a vastly different thing.

Starting a communistic state should not, however, be portrayed entirely in sombre colors. In the darkest days in Russia, art and the opera flourished. Romance, too, played its part. It touched even the chief characters of the revolutionary stage. We were astounded to find one morning that the versatile Kollontay had married the sailor Dybenko. Later, for ordering a retreat before the Germans at Narva, he came under censure. In disgrace he was expelled from office and party, Lenin approving and Kollontay naturally resentful.

Talking with her at this juncture I suggested that Lenin might have gone the way of all flesh, the poison of power entering his veins and inflating his ego. “Bitter as I feel now,” she answered, “I couldn’t think of imputing any action of his to personal motives. No one of the comrades who had worked with Comrade Lenin for ten years could believe that there was a single drop of selfishness in him.”

5. Practise of Communism Rallies the People to the Soviet

Lenin was of course pictured in the bourgeois press as the opposite of this. A fiend incarnate, a selfish, grasping monster. But gradually the real Lenin emerged from this shroud of lies. And as the news spread through Russia that Lenin and his colleagues were taking pot-luck with the people, the masses rallied around them.

The miner in the Urals, inclined to grumble at his meagre ration, remembers that each one draws alike from the common store of food and clothes and shelter. Why, then, should he grumble at his morsel of black bread? At any rate it is as large as Lenin’s. The rankling pangs of injustice are not added to the pangs of hunger.

The peasant wife shivering in the icy blasts that sweep off the Volga knows little of the man who has taken the place of the Czar. But she hears that he often has an unheated room. Now though she suffers from the cold she does not suffer from the inequalities of life.

The engineer at Nizhni, finding the six hundred rubles in the pay-envelope woefully inadequate to cover the needs of his family, begins to be bitter. Then he recollects that the man in the Kremlin draws no more. That helps to take the rancor away.

The Soviet soldier facing the drum-fire of the Allied guns knows that Lenin is also on the firing line though he is in the rear. For danger, like everything else in Russia, has been socialized. No one is immune from it. The percentage of Soviet leaders killed and wounded at the front Uritzky, Volardsky percentage of Soviet soldiers killed and wounded at the front Uritsky, Voladarsky and scores of others have been assassinated while Lenin’s body has twice stopped the assassin’s bullets. To the Red Soldier Lenin then is not someone aloof from the fray, but a comrade-in-arms sharing the risks and hardships of the campaign.

The American Mission to Russia report by Bullitt says:

“Lenin today is regarded as almost a prophet. His picture, usually accompanied by Karl Marx’s, hangs everywhere. When I called on Lenin at the Kremlin I had to wait a few minutes until a delegation of peasants left his room. They had heard in their village that Comrade Lenin was hungry. And they had come hundreds of miles carrying eight hundred puds of bread as the gift of the village to Lenin. Just before them was another delegation of peasants to whom the report had come that Comrade Lenin was working in an unheated room. They came bearing a stove and enough firewood to heat it for three months. Lenin is the only leader who receives such gifts. And he turns them into the common fund.”

Sharing alike in the common wealth and the common dearth created a common bond of sympathy running from Premier to poorest peasant, bringing to the Soviet leaders the increasing support of the people.

6. Practice of Communism Owes Lenin the Pulse of the People

Living so close to the people, the Communist leaders knew the ebb and flow of popular feeling.

Lenin did not need to send out a commission to discover the sentiments and psychology of the people. A man going without food doesn’t have to speculate upon the mood of a hungry man. He knows. Hungering with the people, freezing with the people, Lenin was feeling their feelings, thinking their thoughts, and voicing their desires.

Now this is precisely the way in which the Communist Party claims to function as an instrument directly reflecting the thoughts of the masses and as a mouthpiece articulating them.

The Communists say: “We did not create the Soviets. They sprang out of the life of the people. We did not hatch up some program in our brains and then take it out and superimpose it upon the people. Rather we took our program directly from the people themselves. They were demanding ‘Land to the Peasants,’ ‘Factories to the Workers,’ and ‘Peace to All the World.’ We wrote these slogans upon our banners and with them marched into power. Our strength lies in our understanding of the people. In fact, we do not need to understand the people. We are the people.” This was certainly true of the rank and file of the leaders, who, like the five young Communists we first met in Petrograd, were flesh and bone of the people.

But intellectuals like Lenin how can they speak for the people? How can they understand the hearts and minds of the masses? The answer is that they never can. That is certain. But it is equally certain, as Tolstoy showed, that he who lives the life of the people gets closer than he who holds himself aloof from their struggles. So Lenin had one great advantage over his opponents. He did not have to guess about the feelings of the Ural miner, the Volga peasant or the Soviet soldier. He knew them, approximately, at any rate. For their experiences were his experiences. So while his opponents were fumbling in the dark, Lenin drove ahead with the assurance of the man who knows his ground.

This practice of communism by the Soviet leaders is one of the powerful factors in rallying strength to the Soviet government. Outside Russia this fact has been passed over, or it has been minimized. Lenin, however, did not minimize it. He held it to be essential in the Soviet system. In the vortex of events he took time to write, in the “State and Revolution,” an exposition upon the practice of communism as the true road for proletarian statesmen to take. It is a hard road. There are few that follow in it.

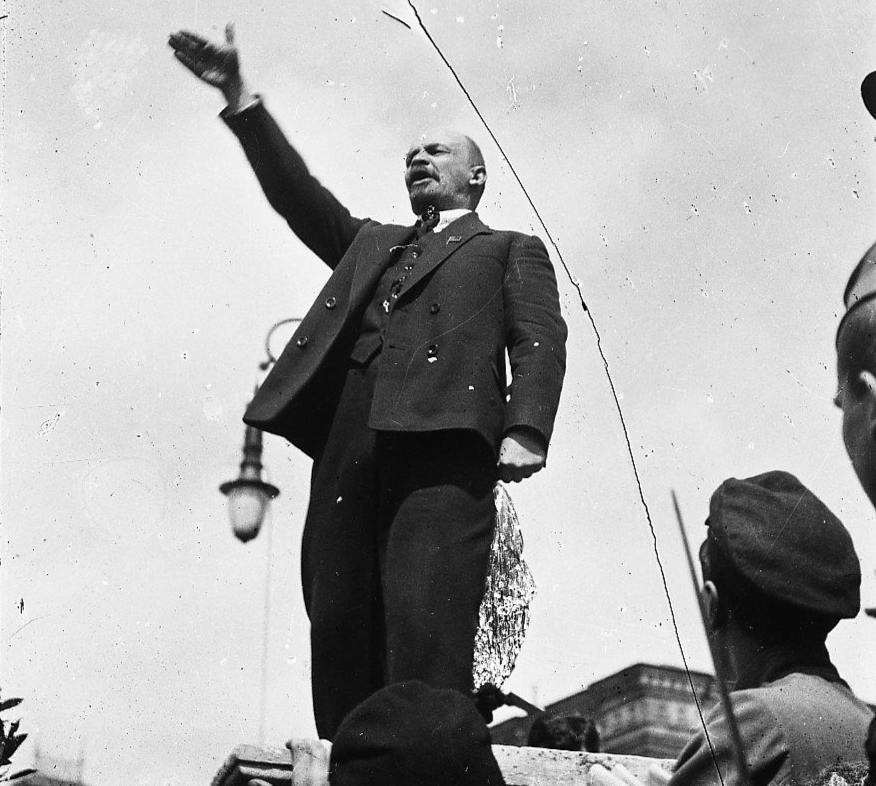

7. Lenin in Public Address

Despite these rigors and the drain of this day and night ordeal, Lenin appeared constantly upon the platform, concise, alert, diagnosing the conditions, prescribing the remedies, and sending his listeners into action to administer them. Observers have wondered at the enthusiasm which Lenin’s addresses roused in the uneducated class. While his speeches were swift and fluent and crowded with facts, they were generally as unpicturesque and unromantic as his platform appearance. They demanded sustained thought and were just the opposite of Kerensky’s. Kerensky was a romantic figure, an eloquent orator, with all those arts and passions which should have swayed, one would think, “the ignorant and illiterate Russians.” But they were not swayed by him. Here is another Russian anomaly. The masses listened to the flashing sentences and magnificent periods of this brilliant platform orator. Then they turned around and gave their allegiance to Lenin, the scholar, the man of logic, of measured thought and academic utterance.

Lenin is a master of dialectics and polemics, aggravatingly self-possessed in debate. And in debate he is at his best, Olgin says: “Lenin does not reply to an opponent. He vivisects him. He is as keen as the edge of a razor. His mind works with an amazing acuteness. He notices every flaw in the line of argument He disagrees with, and he draws the most absurd conclusions from, premises unacceptable to him. At the same time he is derisive. He ridicules his opponent. He castigates him. He makes you feel that his victim is an ignoramus, a fool, a presumptuous nonentity. You are swept by the power of his logic. You are overwhelmed by his intellectual passion.”

Occasionally he relieves the march of his argument by a bit of humor or a stinging retort as: “Comrade Karellin’s queries remind me of the adage, ‘One fool can ask more questions than ten wise men can answer.'” Again, when Radek, the Bolshevik journalist, turned once on Lenin saying, “If there were five hundred brave men in Petrograd we would send you to jail,” Lenin quietly replied, “Some comrades indeed may go to jail, but if you will calculate the probabilities you will see that it is more likely that I will send you than you me.” Occasionally he would bring in a homely incident illustrating the new order: the old peasant woman gathering firewood in the landlord’s forest with the soldier of the new day acting as her protector instead of her persecutor.

Under suffering and the stress of events the fire and passion which lies in the man seemed to have broken through the usual reserve. A recent observer says that in a great meeting Lenin began with sentences somewhat halting and heavy, but as he got under way he spoke more clearly. He became fluent and vivacious, without much external effort but with an increasing internal agitation that was more and more effective. “A sort of controlled pathos pervaded his soul. He used many gestures and kept walking a few steps backward and forward. Remarkably deep and irregular wrinkles formed upon his brow, giving evidence of an intensive pondering, an almost tormenting labor of intellect” Lenin aimed primarily at the intellect, not at the emotions. Yet in the response of his audience one could see the emotional power of sheer intellectuality.

Only once did I see him miss fire. That was at the Mikliailovsky Manege, in December, when the first detachment of the new Red Army was leaving for the front. Flaring torches lit up the vast interior, turning the long lines of armoured cars into a group of strange primeval monsters. Swarming through the great arena and clambering over the cars were the dark figures of the new recruits, poorly equipped in arms, but strong in revolutionary ardor. To keep warm they danced and stamped their feet and to keep good cheer they sang their revolutionary hymns and the folksongs of the villages.

A great shout announced the arrival of Lenin. He mounted one of the big cars and began speaking. In the half darkness the throngs looked up and listened attentively. But they did not kindle to his words. He finished amidst an applause that was far from the customary ovation. His speech that day was too casual to meet the mood of men going out to die. The ideas were commonplace and the expressions trite. There was reason enough for this deadness overwork, preoccupation. But the fact remained. Lenin had met a significant occasion with an insignificant speech. And these workmen felt it The Russian proletarians are not blind hero-worshippers. One cannot long capitalize one’s past exploits and prestige, as the Grandfather and the Grandmother of the Revolution discovered. If one did not acquit oneself like a hero now, one did not get the hero’s need of plaudits.

When Lenin stepped down, Podvoisky announced, “An American comrade to address you.” The crowd pricked up its ears and I climbed upon the big car.

“Oh, good. You speak in English,” said Lenin. “Allow me to be your interpreter.”

“No, I shall speak in Russian,” I answered, prompted by some reckless impulse.

Lenin watched me with eyes twinkling, as if anticipating entertainment. It was not long in coming. After using up the first run of predigested sentences that I always carried in stock, I hesitated, and stopped. I had difficulty in getting the language started up again. No matter what a foreigner does to their tongue, the Russians are polite and charitable. They appreciate the novice’s effort, if not his technic. So my speech was punctured with long periods of applause which gave me each time a breathing spell in which to assemble more words for another short advance. I wanted to tell them that if a great crisis came I should myself be glad to enlist in the ranks of the Red Army. I paused, fumbling for a word. Lenin looked up and asked, “What word do you want?” “Enlist,” I answered. “Vstupit” he prompted.

Thereafter, whenever I was stuck, he would fling the word up to me and I would catch it and hurl it out into the audience, modified, of course, by my American accent. This, and the fact that I stood there in the flesh, a tangible symbol of the internationalism they had heard so much about, raised storms of laughter and thundering applause* In this Lenin joined heartily.

“Well, that’s a beginning in Russian, at any rate,” he said. “But you must keep at it hard. And you,” he said, turning to Bessie Beatty, “you must learn Russian, too. Put an advertisement in the paper asking for exchange lessons. Then just read, write and talk nothing but Russian. Don’t talk with Americans it won’t do you any good, anyhow,” he added humorously. “Next time I see you I’ll give you an examination.”

8. Lenin’s Constant Exposure to Danger

It very nearly came about that there was no next time. As the automobile with Lenin in it swung out of the Manege, there were three sharp reports and three bullets crashed through his car, one of them wounding Platten, the Swiss delegate, who sat in the seat with Lenin. Some assassin up a side street had tried and failed.

The Bolshevik leaders were, of course, in constant danger of their lives. The chief object of attention on the part of the bourgeois plotters was naturally Lenin. In his active brain, they said, were wrought the plans for their undoing. Oh, for a bullet to still that brain! That was the prayer that every day fervently went up from the altars of the counter-revolutionary homes.

In such a home in Moscow we were always welcomed with a lavish hospitality. The great table with its steaming samovar was loaded with fruits and nuts, a bewildering array of zakuska, and what Arthur Ransome called “sweets,” his particular failing. The war had done very handsomely by this household. Speculation in all its branches, running goods by the underground route to Germany, and profiteering, grand and petty, had put this family upon the roof garden. Now suddenly out of the darkness, knocking away the very foundations of the roof garden, came the Bolsheviks. They wanted to put a stop to the war. There was no reasoning with them. Wild, insane fellows I They wanted to put a stop to everything, to speculation, to profiteering, to everything! The only thing to do was to put a stop to them. String them up! Shoot them down! Begin at the top with Lenin.

“I have a million roubles this minute for the man who will kill Lenin,” this rising young Moscow speculator informed me gravely, “and there are nineteen other men whom I can place my hands upon tomorrow, each with a million more for the cause.”

We asked our Bolshevik quintette whether Lenin was aware of the risk he was running. “Yes, he is quite aware of it,” they said. “But he doesn’t worry. You see, nothing really worries him.” And apparently nothing did.

Along a path beset with mines and pitfalls he walked with the composure of a country gentleman, while crises that shook men’s nerves and blanched their faces found him cool and unruffled. Plan after plan of the counter-revolutionists and foreign imperialists to assassinate Lenin miscarried. But on the last of August, 1918, the plotters almost succeeded.

The Premier had finished his address to the 15,000 workmen at the Mikhelson Works. As he was returning to his car, a girl ran out holding a paper as if presenting a petition to the Premier. He reached out to take it and as he did so another girl, Dora Kaplan, fired three shots at him, two of them’ taking effect and stretching him out upon the pavement. He was lifted into his car and driven to the Kremlin. While bleeding profusely from his wounds he insisted upon walking up the steps. He was wounded more seriously than he thought. For weeks he was close to death. The strength left from fighting the fever in his veins he gave to fighting the fever of revenge that ran through the country.

For the masses, enraged that the dark forces of reaction had struck down the man who stood as the symbol of all their liberties and aspirations, struck back at the bourgeoisie and at the monarchists with the Red Terror. Many of the bourgeoisie had to pay with their lives for the assassinations of the commissars and the attempt upon Lenin. So fierce was the wrath of the people that hundreds more would have perished had not Lenin pleaded with the people to restrain their fury. Through all the furor it is safe to say that he was the calmest man in Russia.

9. Lenin’s Extraordinary Self-Composure

On all occasions he maintained the most perfect self-control. Events that stirred others to a frenzy were an invitation to quiet and serenity in him.

The one historic session of the Constituent Assembly was a turbulent scene as the two factions came to death-grips with each other. The delegates, shouting battle-cries and beating on the desks, the orators, thundering out threats and challenges, and two thousand voices, passionately singing the International and the Revolutionary march, charged the atmosphere with electricity. As the night advanced one felt the voltage of the place going up and up. In the galleries we gripped the rails, jaws set and nerves on edge. Lenin sat in a front tier box, looking bored.

At last he rose, and walking to the back of the tribunal he stretched himself upon the red carpeted stairs. He glanced casually around the vast concourse. Then as if saying, “So many people wasting nervous force. Well, here’s one who is going to store some up,” he propped his head on his hand and went to sleep. The eloquence of the orators and the roar of the audience rolled above his head, but peacefully he slumbered on. Once or twice, opening his eyes, he blinked about him, and nodded off again.

Finally, rising, he stretched himself and strolled leisurely down to his place in the front tier box. Seeing our opening, Reed and I slipped down to question him about the proceedings of the Constituent Assembly. He replied indifferently. He asked about the activities of the Propaganda Bureau. His face brightened up as we told him how the material was being printed by tons, that it was really getting across the trenches into the German army. But we found it hard to work in the German language.

“Ah!” he said with sudden animation, as he recalled my exploits on the armored car, “and how goes the Russian language? Can you understand all these speeches now?”

“There are so many words in Russian,” I replied evasively. “That’s it,” he retorted. “You must go at it systematically. You must break the backbone of the language at the outset. I’ll tell you my method of going at it.”

In essence, Lenin’s system was this: First; learn all the nouns, learn all the verbs, learn all the adverbs and adjectives, learn all the rest of the words; learn all the grammar and rules of syntax, then keep practicing everywhere and upon everybody. As may be seen, Lenin’s system was more thorough-going than subtle. It was, in short, his system of the conquest of the bourgeoisie applied to the conquest of a language, a merciless application to the job. But he was quite exercised over it.

He leaned over the box, with sparkling eyes, and drove his words home with gestures. Our fellow reporters looked on enviously. They thought that Lenin was violently excoriating the crimes of the opposition, or divulging the secret plans of the Soviet, or spurring us to greater zeal for the Revolution. In a crisis like this, surely only such themes could draw forth this burst of energy from the head of the Great Russian state. But they were wrong. The Premier of Russia was merely giving an exposition on how to learn a foreign language and was enjoying the diversion of a little friendly conversation.

In the tension of great debates, when his opponents were lashing him unmercifully, Lenin would sit in serene composure, even extracting humor from the situation. After his address at the Fourth Congress, he took his seat upon the tribunal to listen to the assaults of his five opponents. Whenever he thought that the point scored against him was good, Lenin would smile broadly, joining in the applause. Whenever he thought it was ridiculous, Lenin, smiling ironically, would give a mock applause, striking his thumb-nails together.

10. Lenin’s Manner In Private Address

Only once did I see evidence of weariness in him. After a midnight meeting of the Soviet, he stepped into the elevator of the National Hotel with his wife and sister. “Good evening,” he said, rather wearily. “No,” he added, “it’s good morning. I’ve been talking all day and night, and I’m tired. I’m riding the elevator though it is but one flight up.”

Only once did I ever see him hurried or rushed. That was in February, when the Tauride palace was again the scene of a fevered conflict the debate over war or peace with Germany. Suddenly he appeared, and with quick, vigorous stride was fairly hurtling himself down the long hall toward the platform entrance. Professor Charles Kuntz and I were lying in wait for him, and hailed him with “Just a minute, Tovariskch Lenin.”

He checked his headlong flight and came to attention in almost military fashion, bowed very gravely, and said, “Will you be so good as to let me go this time, comrades? I haven’t even as much as a second. They are awaiting me inside the hall. I beg you to excuse me this time, please.” With another bow and a handshake he was off in full stride again.

Wilcox, an anti-Bolshevik, commenting on the amenity of Lenin in intimate relationships, says that an English merchant, in order to rescue his family from a critical situation, went to seek Lenin’s personal aid. He was astonished to find the “blood-thirsty tyrant” a mild-mannered man, courteous and sympathetic in bearing, and almost eager to afford all assistance in his power.

In fact, at times he seemed over-courteous, exaggeratedly so. This may have been due to his use of English, lifting bodily from the books the elaborate forms of polite conversation. More probably, it was part of his technic in social intercourse, for Lenin was highly efficient here as elsewhere. He refused to squander his time upon non-essential persons; he was not easily accessible. In his anteroom is this notice:

“Visitors are asked to take into consideration that they are to speak to a man whose business is enormous. He asks them to explain clearly and briefly what they have come to say.”

It was hard to get at Lenin, but once you did you had all there was of him. All his faculties were focused upon you in a manner so acute as to be embarrassing. After a polite, almost an effusive, greeting, he drew up closer until his face would be no more than a foot away. As the conversation went on he often came still closer, gazing into your eyes as if he were searching out the inmost recesses of your brain and peering into your very soul. Only an extraordinarily brazen liar like Malinovsky could withstand the steady impact of that gaze.

We often met a certain Socialist who in 1905 had taken part in the Moscow uprising and had even fought well on the barricades, A career and the comforts of life had weaned him from his first ardent devotion. He wore now an air of prosperity, acting as correspondent for an English newspaper syndicate and Plekhanov’s Yedinstvo. Bourgeois writers were regarded by Lenin as wasters of time; but by playing up his past revolutionary record this man had managed to secure an appointment with Lenin. He was in high spirits as he went away to meet it. Some hours later I saw him in a state of perturbation. He explained:

“When I walked into the office, I referred to my part in the 1905 revolution. Lenin came up to me and said, ‘Yes, comrade, but what are you doing for this revolution?’ His face was not more than six inches away and his eyes were looking straight into mine. I spoke of my old days on the Moscow barricades, and took a step backwards. But Lenin took a step forward, not letting go my eyes, and said again, ‘Yes, comrade, but what are you doing for this revolution?’ It was like an X-ray as if he saw all my deeds of the last ten years. I couldn’t stand it I had to look down like a guilty child. I tried to talk, but it was no use. I had to come away.” A few days later this man threw in his lot with this revolution and became a worker for the Soviet.

11. Lenin’s Sincerity and Hatred of Unreality

One of the secrets of Lenin’s power is his terrible sincerity. He was sincere with his friends. He was gratified, of course, with each accession to the ranks, but he would not enlist a single recruit by painting in roseate hues the conditions of service, or the future prospects. Rather he tended to paint things blacker than they were. The burden of many of Lenin’s speeches was: “The goal the Bolsheviks are striving for is far away further away than most of you dream. We have led Russia along a rough road, but the course we follow will bring us more enemies, more hunger. Difficult as the past has been, the future promises harder things harder than you imagine.” Not an alluring promise. Not the usual call to arms! Yet as the Italians rallied to Garibaldi, who came offering wounds, prison and death, the Russians rallied to Lenin. This was a little discomforting to one expecting the leader to glorify his cause and to urge the prospective convert into joining it. He left the urge to come from within.

Lenin is sincere even with his avowed enemies. An Englishman, commenting on his extraordinary frankness, says his attitude was like this: “Personally, I have nothing against you. Politically, however, you are my enemy and I must use every weapon I can think of for your destruction. Your government does the same against me. Now let us see how far we can go along together.”

This stamp of sincerity is on all his public utterances. Lenin is lacking in the usual outfit of the statesman-politician bluff, glittering verbiage and success-psychology. One felt that he could not fool others even if he desired to. And for the same reasons that he could not fool himself: His scientific attitude of mind, his passion for the facts.

His lines of information ran out in every direction, bringing him multitudes of facts. These he weighed, sifted and assayed. Then he utilized them as a strategist, a master chemist working in social elements, a mathematician. He would approach a subject in this way:

“Now the facts that count for us are these: One, two, three, four ” He would briefly enumerate them. “And the factors that are against us are these.”

In the same way he would count them up, “One, two, three, four Are there any others?” he would ask. We would rack our brains for another, but generally in vain. Elaborating the points on each side, pro and contra, he would proceed with his calculation as with a problem in mathematics.

In his glorification of the fact he is the very opposite of Wilson. Wilson as a word-artist gilds all subjects with glittering phrases, dazzling and mesmerizing the people and blinding them to the ugly realities and crass economic facts involved. Lenin conies as a surgeon with his scalpel. He uncovers the simple economic motives that lie behind the grand language of the imperialists. Their proclamations to the Russian people he strips bare and naked, revealing behind their fair promises the black and grasping hand of the exploiters.

Relentless as he is toward the phraseologists of the Right, he is equally as hard upon those phraseologists of the Left who seek refuge from reality in revolutionary slogans. He feels it his duty “to pour vinegar and bile into the sweetened waters of revolutionary democratic eloquence,” and he treats the sentimentalist and shouter of shibboleths with caustic ridicule.

When the Germans were making their drive upon the Red Capital a flood of telegrams poured in on Smolny from all over Russia, expressing amazement, horror and indignation. They ended with slogans like “Long live the invincible Russian proletariat!” “Death to the imperialistic robbers!” “With our last drop of blood we will defend the Capital of the Revolution!”

Lenin read them and then dispatched a telegram to all the Soviets, asking them kindly not to send revolutionary phrases to Petrograd, but to send troops; also to state precisely the number of volunteers enrolled, and to forward an exact report upon the arms, ammunition and food conditions.

12. Lenin at Work In a Crisis

With the advance of the Germans came the flight of the foreigners. The Russians manifested a mild surprise that all those who had so wildly cried to them, “Kill the Huns!” now fled precipitately when the Hun came within killing range. It would have been good to join the hegira, but there was my pledge made upon the armored car. So I went out to join the Red Army. Bukharin, the Left-Bolshevik, insisted that I should see Lenin.

“My congratulations! My felicitations!” said Lenin. “It looks very bad for us just now. The old army will not fight. The new one is largely upon paper. Pskov has just been surrendered without resistance. That is a crime. The President of the Soviet ought to be shot. Our workers have great self-sacrifice and heroism. But no military training, no discipline.”

Thus in about twenty short sentences he summed up the situation, ending with, “All I can see is peace. Yet the Soviet may be for war. In any case, my congratulations for joining the Revolutionary Army. After your struggle with the Russian language you ought to be in good training to fight the Germans.” He ruminated a moment and added:

“One foreigner can’t do much fighting. Maybe you can find others.” I told him that I might try to form a detachment.

Lenin was a direct actionist. A plan conceived, at once he proceeded to put it into execution. He turned to the telephone to ring up Krylenko, the Soviet commander. Failing, he picked up a pen and scribbled him a note.

By night we had formed the International Legion and issued our call summoning all men speaking foreign languages to enroll in the new company. But Lenin did not drop the matter there. He was not content merely with inaugurating something in the grand manner. He followed it up relentlessly and in detail. Twice he telephoned the Pravda office instructing them to print the call in Russian and in English. Then he telegraphed it through the country. Thus, while opposing the war, and particularly those who were intoxicating themselves with revolutionary phrases about it, Lenin was mobilizing every force to prepare for it.

He sent an automobile with Red Guards to the fortress of Peter and Paul to fetch part of the counter-revolutionary staff imprisoned there.

“Gentlemen,” said Lenin, as the generals filed into his office, “I have brought you here for expert advice. Petrograd is in danger. Will you be good enough to work out the military tactics for its defense?” They assented.

“Here are our forces,” resumed Lenin, indicating upon the map the location of the Red troops, munitions and reserves. “And here are our latest reports upon the number and disposition of the enemy troops. Anything else the generals desire they will call for.”

They set to work and toward evening handed him the result of their deliberations. “Now,” said the generals ingratiatingly, “will the Premier be good enough to allow us more comfortable quarters?”

“My exceeding regrets,” replied Lenin. “Some other time, but not just now. Your quarters, gentlemen, may not be comfortable, but they have the merit of being very safe.” The staff was returned to the fortress of Peter and Paul.

13. Lenin as a Prophet and Statesman

It is clear that Lenin’s prowess as a statesman and seer arises not from any mystic intuition or power of divination, but from his ability to amass all the facts in the case and then to utilize them. He showed this ability in his work, “The Development of Capitalism.” There Lenin challenged the economic thought of his day by asserting that half the Russian peasants had been proletarianized, that, despite their possession of some land, these peasants were in effect “wage-earners with a piece of land.” Bold and daring as the assertion was, it was corroborated by investigation in later years. Lenin had not merely guessed at it. It was his verdict after extensive marshalling of statistics in the Zemstvos and in other fields.

One day, discussing with Peters the roots of Lenin’s prestige, he said, “Often in the closed sessions of our party Lenin made certain proposals based upon his analysis of the situation. We voted them down. Later on it turned out that Lenin was right and we were wrong.” On the question of tactics there have been Homeric struggles between Lenin and other members of the party, in which later events have generally vindicated his judgment.

Prominent Bolshevik leaders like Kamenev and Zinoviev held that in the proposed November revolution it was impossible to succeed. Lenin said, “It is impossible to fail.” Lenin was right. The Bolsheviks made a gesture, and the governmental power fell into their hands. None were more surprised than the Bolsheviks at the ease with which it was accomplished.

The other Bolshevik leaders said that though they might take the power they could not hold it. Lenin said, “Every day will bring us fresh strength.” Lenin was right. After two years of fighting against enemies hemming them in from all sides, the Soviet advances on every front.

Trotzky pursued his juggling tactics with the Germans, decoying them along but refusing to sign the treaty. Lenin said, “Don’t play with them. Sign the first treaty offered, however bad, or we shall have to sign a worse one.” Again Lenin was right. The Russians were forced to sign “the brigand’s” “the bandit’s” peace of Brest-Litovsk.

In the Spring of 1918, while the whole world was ridiculing the idea of a German revolution, and the Kaiser’s army was smashing the Allied line in France, Lenin in a conversation with me said, “The Kaiser’s downfall will come within the year. It is absolutely certain.” Nine months later the Kaiser was a fugitive from his own people.

“If you are going back to America.” said Lenin to me in April, 1918, “you should start very soon, or the American army will meet you in Siberia.” That was an amazing statement, as at that time, in Moscow, we had come to believe that America was cherishing only the largest good-will toward the new Russia. “That is impossible,” I protested. “Why, Raymond Robins thinks there is even a possibility of recognition of the Soviets.”

“Yes,” said Lenin, “but Robins represents the liberal bourgeoisie of America. They do not decide the policy of America. Finance capital does. And finance capital wants control of Siberia. And it will send American soldiers to get it.” This point of view was preposterous to me. Yet later, June 29, 1918, I saw with my own eyes the landing of American sailors in Vladivostok, while Czarists, Czechs, British, Japanese and other Allies hauled down the flag of the Soviet Republic and ran up the flag of the old autocracy.

Lenin’s predictions have so often been verified by the events that his view of the future is, to say the least, interesting. Here is the gist of Naudeau’s famous interview as it appeared in the Paris Temps in April, 1919.

“The future of the world?” said Lenin. “I am not a prophet, but this much is certain. The capitalist state, of which England is an example, is dying out. The old order is doomed. The economic conditions arising out of the war are driving towards the new order. The evolution of mankind inevitably leads to Socialism.

“Who would have believed some years ago that the nationalization of railroads in America was possible? And we have seen that Republic buy all the grain in order to use it to the fullest advantage of the state. All that is said against the state has not retarded this evolution. True it is necessary to create and contrive new means of control in order to remedy the imperfections. But any attempts to prevent the state from becoming sovereign are futile. For the inevitable comes and comes of its own momentum. The English say, ‘The proof of the pudding is in the eating.’ Say what you will of the Socialistic pudding, all the nations eat and will eat more and more of it.

“To sum up. Experience seems to prove that each human group goes on towards Socialism by its own particular way. Even the Letts go at it differently from the Russians. There will be many passing forms and variations, but they are all different phases of a revolution which tends toward the same end. If a Socialistic regime is established in France or Germany, it will be much easier to perpetuate it than here in Russia. For in the West Socialism will find frameworks, organizations, all kinds of intellectual auxiliaries and materials, which are not to be found in Russia.”

14. Lenin’s Attitude Toward Men of Brains

“For every honest Bolshevik there are thirty-nine scoundrels and sixty fools.” This widely quoted sentence has been put Into the mouth of Lenin in an attempt to picture him as the grand patrician with cynical mistrust of the masses. To support this curious charge a statement of fifteen years ago is dug up. It says that the working-classes of themselves developed only a trade-unionist consciousness, that is, the sense of organization, striking against employer, the eight-hour day, etc. But the ideas of Socialism have come to the workers largely from outside, from the intellectuals.

It is true that in all their actions and decrees Lenin and the Soviet government show the high value they set upon brains. In every realm Lenin defers to the expert. He looks to the generals even of the Czar’s regime as the authorities in military affairs. If Marx, the German, is Lenin’s authority in revolutionary tactics, Taylor, the American, is his authority in efficiency production. And he always was stressing the value of the expert accountant, the big engineer, the specialist in every field of activity. He believed that the Soviet would be a magnet drawing them from around the world. He believed they would see in the Soviet system a wider range for the play of their creative abilities than in any other system.

It is said that Harriman was worn out not so much by the task of operating his great railroad as by the problem of financing it. Under the Soviet system he would not have to divert his energy from the work of administering to financing. For, under the Soviet, economic power is delegated to the head administrator quite as we delegate political power to our representative in Congress. He is given the vast resources of Russia to work upon. Besides, Russia under the Soviet offers to the engineer or administrator not only its vast wealth to work upon but also a labor force, enthusiastic and alive, with which to work it.

This latter condition does not obtain under the capitalist system where the workman’s greatest interest lies in his wages rather than in his work, and where the management and the labor force come into constant conflict Under the Soviet the energies of the men, instead of being spent in quarreling over the division of the product, are liberated for the task of larger production. Lenin believed in the great results arising from the Soviet system calling out the enthusiastic creative energies of the masses and at the same time giving a free hand to the men of brains and genius.

In his survey of social forces Lenin made his estimate of the value of all the different elements. The intellectuals had their place before and after the Revolution. As agitators they could help make the Revolution possible. As experts with skill and technic they could help make the Revolution permanent and stable.

15. Lenin ‘s Attitude Toward Americans, Capitalists and Concessions

American technicians, engineers and administrators Lenin particularly held in high esteem. He wanted five thousand of them, he wanted them at once, and was ready to pay them the highest salaries. He was constantly assailed for having a peculiar leaning toward America. Indeed, his enemies cynically referred to him as “the agent of the Wall Street bankers,” and in the heat of debate the extreme Left hurled this charge in his face.

As a matter of fact, American capitalism was to him not less evil than the capitalism of any other nation. But America was so far away. It did not offer a direct threat to the life of Soviet Russia. And it did offer the goods and experts that Soviet Russia needed. “Why is it not then to the mutual interest of the two countries to make a special agreement?” asked Lenin.

But is it possible for a communistic state to deal with a capitalistic state? Can the two forms live side by side? These questions were put to Lenin by Naudeau.

“Why not?” said Lenin. ‘We want technicians, scientists and the various products of industry, and it is clear that we by ourselves are incapable of developing the immense resources of this country. Under the circumstances, though it may be unpleasant for us, we must admit that our principles, which hold in Russia, must, beyond our frontiers, give place to political agreements. We very sincerely propose to pay interest on our foreign loans, and in default of cash we will pay them in grain, oil and all sorts of raw materials in which we are rich.

“We have decided to grant concessions of forests and mines to citizens of the Entente powers, always on the condition that the essential principles of the Russian Soviets are to be respected. Furthermore, we will even consent not cheerfully, it is true, but with resignation to the cession of some territory of the old Empire of Russia to certain Entente powers. We know that the English, Japanese and American capitalists very much desire such concessions.

“We have granted to an international association the construction of the Peliky Severity, The Great Northern Line. Have you heard of it? It is about 3,000 versts of railroad, starting at Soroka, near the Gulf of Onega, and running by way of Kotlas across the Ural mountains to the Obi Riven Immense virgin forests with 8,000,000 hectares of land and all kinds of unexploited mines will fall within the domain of the constructing company.

“This state property is ceded for a certain time, probably eighty years, and with the right of redemption. We exact nothing drastic of the association. We ask only the observance of the laws passed by the Soviet, like the eight-hour day and the control of the workers’ organizations. It is true that this is far from Communism. It does not at all correspond to our ideal, and we must say that this question has raised some very lively controversies in Soviet journals. But we have decided to accept that which the epoch of transition renders necessary.”

“So you believe, then,” said Naudeau, “that, considering the dangers run here by foreign capitalists dangers which do not seem to have been removed, and which one fears may be aggravated at any time you believe that financiers will have courage enough to come to Russia and let it swallow up new treasures? They will not begin such a task without the protection of an armed force from their own country. Will you consent to such an occupation?”

“It will be quite superfluous,” said Lenin, “because the Soviet Government will observe faithfully what they have bound themselves to observe. But all points of view may be considered.”

The reports from the Great Moscow Economic Council in June, 1919, show Lenin with Chicherin battling for the policy of economic alliance with America against the engineer Krassin leading the fight for economic alliance with Germany.

16. Lenin’s Tremendous Faith in the Proletarians

To Lenin, of course, the driving force of the Revolution, its soul and its sinew, was the proletariat. The only hope of a new society lay in the masses. This was not the popular view. The conception of the Russian masses generally current makes them but shambling creatures of the soil, shiftless, lazy, illiterate, with dark minds set only upon vodka, devoid of idealism, incapable of sustained effort.

Over against this stands Lenin’s estimate of the “ignorant” masses. Through the long years, in season and out of season, he insisted upon their resoluteness, their tenacity, their capacity for sacrificing and suffering, their ability to grasp large political ideas, and the great creative and constructive forces latent within them. This seems like an almost reckless trust in the character of the masses. How far have results justified Lenin’s venture of faith in the Russian workingmen?

Their ability to grasp large political ideas has astounded all observers who have gone below the surface in Russia. It made a member of the Root Mission ask in wonder, “How came so much of the mass of the Russian people, viewed by all the truly learned as ignorant and stupid, to seize upon a social philosophy so new to the rest of the world and so far in advance of it?” The hundreds of young men sent over by the Y.M.C.A. and other agencies were a puzzle to the Russian workingman. These “educators” were the graduates of American universities and yet they did not know the difference between Socialism, Syndicalism and Anarchism, which was the ABC in the education of millions of Russian workingmen.

The American propaganda agents spread President Wilson’s Fourteen-Points Speech in Russia by hundreds of thousand of copies. Passing these out to workers or peasants, they would ask, “What do you think of it?”

“It sounds very good,” they would generally reply, “but there is nothing back of it. President Wilson may have these ideals in his head, but there will be none of these ideals in the Treaty of Peace unless the workers have control of the government.”

An eminent American professor who heard the Russians say this laughed at their skepticism. Today he laughs at his own credulity and wonders how these “dark people” in the little Soviets in the remote parts of backward Russia had a better grasp on international politics than himself.

The British worked on the plan that it was only necessary to appeal to the immediate self-interest of the masses. They arrived in Archangel bringing jam, whiskey and white flour with which to seduce the people. The famished folk rejoiced to receive the gifts, but when they saw that these were bribes to blind them and that the price of these goods was the integrity and freedom of Russia, they turned upon the invaders and drove them from the country.

Time has also justified Lenin’s faith in the tenacity and resoluteness of the Russian masses. Compare the dire prophecies of 1917 with the facts of to-day. “Three days and their power is gone,” croaked the enemies of the Soviets then. The three days passed into as many more, and the cry became, “Three weeks is the utmost that the Soviet can last.” Again they had to change the cry. This time it became “Three months.” Now, after eight times three months, the best the enemies of the Soviets can offer their backers is “Three years.”

17. The Achievements of the Workers and Peasants greater than his Expectations

The strength and persistence of the Soviet Government does not lie, as some infer, in the violation of all law, the strange whimsy of an inscrutable Providence. It rests just where Lenin said it would on the solid achievements of the workers and peasants.

In the economic field they have started new processes for the manufacture of linen, matches and the utilization of the great peat-beds of Russia. They have completed vast engineering enterprises ranging from the setting-up of power-plants and electric stations to the dredging of the great canal between the Baltic Sea and the Volga River and the building of hundreds of versts of railways.

In the military realm the workers and peasants submitted themselves to a stern military discipline which transformed the Red Army into one of the most formidable fighting-machines in the world. These proletarians have a distinct morale and spirit Hitherto they have always fought in the interests of some superior caste. Now for the first time they are fighting consciously battles in their own interest and in the interests of the toiling and exploited peoples of the world.

But it is in the cultural realm that the triumphs of the “dark people” have been most significant. Make man free and he creates.

Under the quickening touch of the new spirit there have grown up ten new universities, scores of theatres, thousands of libraries, and common schools by the tens of thousands.

It was these realities that converted Maxim Gorky from a bitter enemy into a partisan of the Soviets. “The cultural creative work of the Russian Government,” he writes, “is about to have a scope and form hitherto unknown in the history of mankind. The historian of the future will be unable to avoid admiring the magnificence of this last year of the Russian workers in the realm of culture.”

More stupendous and significant are these achievements when one considers the handicaps under which the masses labored. When they took over the government they had as their heritage a people brow-beaten, impoverished and oppressed for centuries. The Great War had killed two million of their able-bodied men, wounded and crippled another 3,000,000 and left them with hundreds of thousands of orphans and hundreds of thousands of the blind, the deaf and the dumb. The railways were broken down, the mines flooded, the reserves of food and fuel nearly gone. The economic machinery, dislocated by the war and further shattered by the Revolution, had suddenly thrown upon it the task of demobilizing 12,000,000 soldiers. They raised a bumper grain crop, but the Czechs, supported by the Japanese, French, British and Americans, cut them off from the grain fields of Siberia, and the other counter-revolutionaries from the grain fields of the Ukraine.

“Now,” they said, “the bony hand of hunger will clutch the people by the throat and bring them to their senses.” Because they separated the church from state they were excommunicated. They were sabotaged by the old officials, deserted by the intelligentzia and blockaded by the Allies. The Allies tried by all manner of threats, bribery and assassination to overthrow their government, British agents blowing up the railway bridges to prevent supplies reaching the big cities, and French agents, under safe-conduct from their consulates, putting emery in the bearings of the locomotives. Facing these facts, Lenin said: “Yes, we have mighty enemies, but against them we have the iron battalion of the proletarians. The vast majority are not as yet truly conscious and they are not active. And the reason is clear. They are war weary, hungry and exhausted. The Revolution now is only skin deep, but with rest there will come a big psychological change. If It only comes in time the Soviet Republic is saved.”

To Lenin’s mind the episode of November, 1917 the masses spectacularly crashing into power was not the Revolution. But these masses becoming conscious of their mission, passing into discipline and orderly work, and bringing into the field their great creative and constructive forces that would be the Revolution.

In those early days Lenin was never certain that the Soviet Republic was saved. “Ten days more!” he exclaimed, “and we shall have lasted as long as the Paris Commune.” In opening his address to the Third All-Russian Congress in Petrograd, he said, “Comrades, consider that the Commune of Paris held out for seventy days. We have already lasted for two days more than that.”

More than ten times seventy days the great Russian Commune has held out against a world of enemies. Great was the faith of Lenin in the tenacity, the perseverance, the resoluteness, the heroism, and the economic, military and cultural potentialities of the proletarians. Their achievements are not merely the vindication of his zealous faith. They are a source of amazement to himself.

18. The Russian Revolution a Success apart from Lenin

As Lenin arises in Russia to become the central figure on the world’s stage, a storm of controversy rages around him.

To the terrified bourgeoisie he is a bolt from the blue, an awful portent of nature, a world-devastating scourge.

To the mystically minded he is the great “Mongolian Slav,” mentioned in that strangely fulfilled pre-war prophecy attributed to Tolstoy. After predicting the outbreak of the Great War, its causes and its place, it goes on to say: “I see all Europe in flames and bleeding. I hear the lamentations of huge battlefields. But about the year 1915 a strange figure from the North a new Napoleon enters the stage of the bloody drama. He is a man of little military training, a writer or a journalist, but in his grip most of Europe will remain till 1925.”

To the reactionary Church Lenin is the Anti-Christ. The priests try to rally the peasants around the sacred banners and ikons and lead them against the Red Army. But the peasants say, “He may be Anti-Christ, but he brings us land and freedom. Why then should we fight him?”

To the man in the street Lenin has almost a superhuman significance. He is the Maker of the Russian Revolution, the Founder of the Soviet, the cause of all that Russia is to-day. “Kill Lenin and Trotzsky and you kill the Revolution and the Soviet.”

This is to view history as the product of Great Men, as if great events and epochs were determined by their great leaders. It is true that a whole epoch may express itself in a single personality, and that a great mass-movement may focus itself in an individual. But that is the utmost that can be conceded to the Carlylean view.

Certainly any interpretation of history that makes the Russian Revolution hinge upon a single person or group of persons is misleading. Lenin would be the first to scoff at the idea that the fortunes of the Russian Revolution lie in his hands or in the hands of his confreres.

The fate of the Russian Revolution lies in the source whence it has sprung in the hearts and hands of the masses. It lies back in those economic forces, the pressure of which has set those masses into motion. For centuries these masses had been quiescent, patient, long-suffering. All across the vast reaches of Russia, over the Muscovite plains, the Ukranian steppes, and along the great rivers of Siberia, they toiled under the lash of poverty, chained by superstition, their lot little better than that of the beast But there is an end to all things even the patience of the poor.

In March, 1917, with a crash heard round the world, the city masses broke their fetters. Army after army of soldiers followed their example and revolted. Then the Revolution permeated the villages, going deeper and deeper, firing the most backward sections with the revolutionary spirit, until a nation of 180,000,000 has been stirred to its depths seven times as many as in the French Revolution.

Caught by a great vision, a whole race strikes camp, and moves out to build a new order. It is the most tremendous movement of the human spirit in centuries. Based on the bed-rock of the economic interest of the masses, it is the most resolute strike for justice in history. A great nation turns crusader and, loyal to the vision of a new world, marches on in the face of hunger, war, blockade and death. It drives ahead, sweeping aside the leaders who fail them, following those who answer their needs and their aspirations.

In the masses themselves lies the fate of the Russian Revolution in their discipline and devotion. Fortune, indeed, has been very kind to them. It gave them for guide and interpreter a man with a giant mind and an iron will, a man of vast learning and fearless action, a man of the loftiest idealism and the most stern, practical sagacity.

Lenin: The Man and his Work by Albert Rhys Williams, Raymond Robins and Arthur Ransome. Scott and Seltzer Publishers, New York. 1919.

Introduction. Biographical Sketch. Ten Months with Lenin by Albert Rhys Williams, Impressions As Told to William Hard by Raymond Robins, Lenin in 1919, Conservative Opinions on Lenin, Two Adverse Opinions by Arthur Ransome, Lenin by Anise. 202 pages.

PDF of book: https://archive.org/download/leninmanhiswork00willuoft/leninmanhiswork00willuoft.pdf