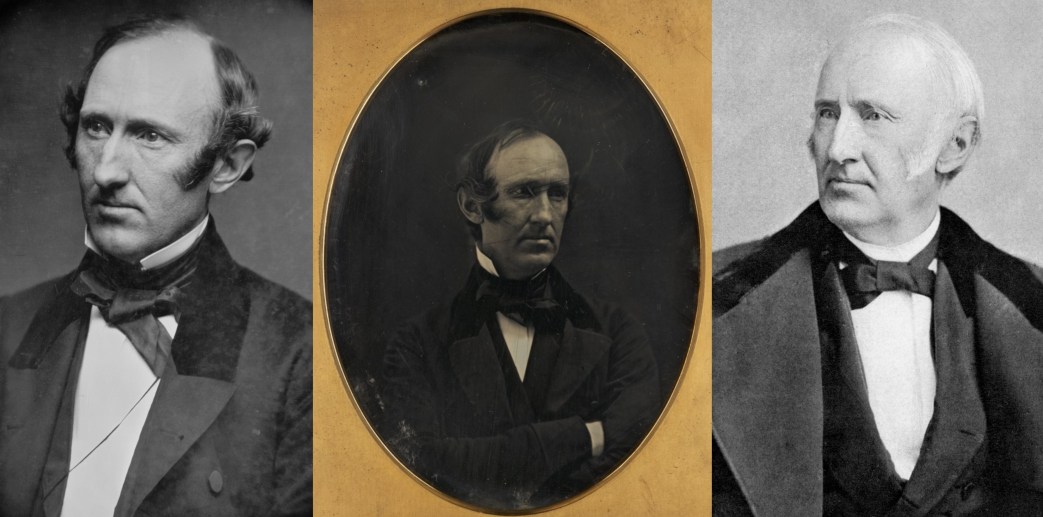

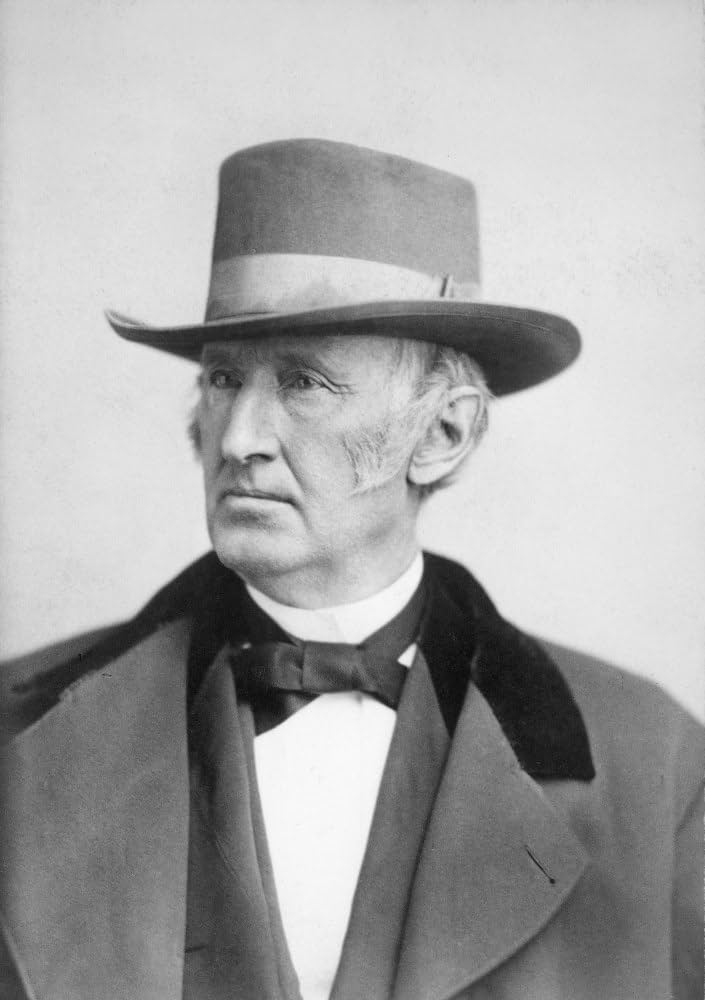

Today, November 29th, is the birthday of Wendell Phillips, born in 1811. Leading abolitionist of his generation, a legendary orator, founding member of the First International, and champion of all oppressed, Phillips was the foremost U.S. radical of the 19th century. On the 100th anniversary of his birth in 1911 German-American revolutionary Max Baginski wrote this ode to Phillips for Emma Goldman’s ‘Mother Earth.’

‘Wendell Phillips, the Agitator’ by Max Baginski from Mother Earth. Vol. 6 No. 9. November, 1911.

ON the twenty-ninth of November, it will be one hundred years since Wendell Phillips was born. He died the second of December eighteen hundred and eighty-four; and although that is but a short time ago, yet he is already nearly forgotten. Officially the American republic does not honor his memory; for he was neither a statesman in the service of Mammon, nor a general with a famous and a bloody record.

Wendell Phillips was a powerful agitator who sought no other success than the enlightenment and emancipation of the people. Agitation to him was a means by which to counteract the poison of despotism that for its own aggrandizement keeps the masses in ignorance and inertia. Such agitation is still tabooed. The only kind of agitation that meets with the approval of the leaders of the nation is that which keeps alive and active the superstition of the ballot, to the end that they may realize on the spoils of victory.

Barely twenty years of age, Wendell Phillips was on an easy road to a successful career. Endowed with brilliant abilities and having splendid connections, he opened a law office; but the spirit of the time willed it otherwise:

“In the early thirties,” says Phillips’ biographer, Lorenzo Sears, “a movement was under way which was so unpopular that its promoters might as well have been paroled convicts.”

Young Phillips threw his whole soul into this unpopular movement of the Abolitionists. He gave up his profession, “because he could not conscientiously follow it under a constitution which recognized property in human beings, and sanctioned their return to bondage after their escape from it.”

It was very dangerous then to be an Abolitionist. William Lloyd Garrison was made the victim of a well-dressed mob and dragged through the streets of Boston. Publishers of Abolitionist papers were threatened and their offices demolished. In 1837 Elijah Parrish Lovejoy fell a victim in Alton, Illinois, to the revolver shots of the defenders of slavery. The printing plant of his paper, the Observer, had been destroyed four times in succession. His assailants were mostly well-to-do citizens, who saw in slavery a sacred and unimpeachable institution. Whoever dared to attack it, was a criminal and an atheist who sinned against the Lord himself. This anti-Abolitionist fury was fostered not a little by the government. President Andrew Jackson issued a proclamation against the “incendiary agitation” of the opponents of slavery. Congress, too, lent its aid to break down the “constitutional rights of petition, the freedom of the press and speech,”

As wage slavery is to-day, so was black slavery then considered a God-anointed institution. The language, misrepresentations and calumnies used against the Abolitionists are almost identical: with those hurled at the Anarchists in the present day.

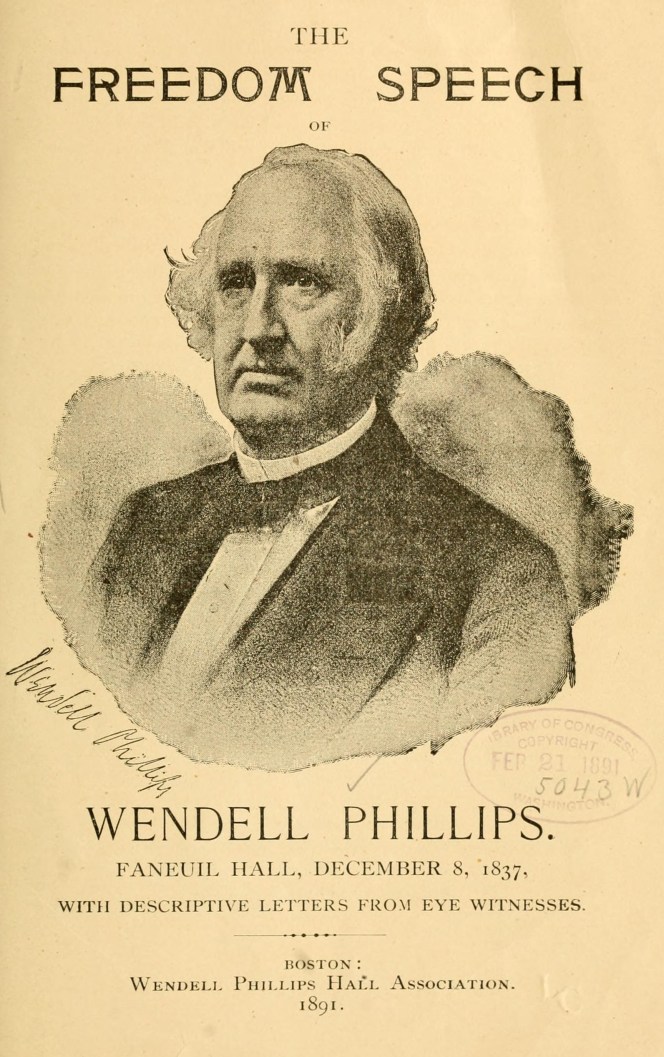

Thanks to his intensity, enthusiasm and brilliant oratory, Phillips was the most dangerous opponent, and therefore incurred the bitterest ‘hatred of the slave holders. Time and again his meetings were broken up. Fanueil Hall, the scene of many storms, was eventually closed to the friends of the black man, instead it was turned over-to the defenders of slavery. The police willingly closed both eyes in the presence of these wild and savage scenes enacted by the rich mob, by politicians and ministers of the gospel; so that Phillips once made this caustic remark: “Abolitionists are accustomed to live without government.”

The attitude of respectable society toward the abolition of slavery is elucidated in an address delivered by Wendell Phillips as President of the New England Anti-Slavery Convention, in the fifties:

“For the twenty years these meetings have been held in the city of Boston no clergyman, no officer of the State, no man of any social standing or position of influence, has stood on this platform.”

Experience and the bitter struggle taught him that the State and the Church are the most pernicious obstacles in the path of freedom. “The constitution and the Church are in the way of emancipation,” he said. Then again, he advised against voting, “under a constitution that protects the slave-catcher.” Agitation and distrust of politics were his slogan. The following words from one of his speeches are still of value:

“If the people do not rule, it is because they are willing to have politicians rule, instead.”

He understood then that ownership and wealth will eventually dominate this country. The Union, he said, had produced wealth but not men greater than Daniel Webster, Caleb Cushing and Franklin Pierce. These, Phillips considered, but lukewarm and weak, ready to follow the wind.

When the Republican party was launched, many Abolitionists placed great faith in it; but our agitator declared that the time demanded not politicians but a revolution. No wonder he preferred John Brown and his direct methods, to the parleying of politicians. In his oration after the execution of John Brown, on the second of December, 1859, we find these characteristic words:

“Men say that he should have remembered that lead is wasted in bullets, and is much better made into types! Well, John Brown fired one gun, and has had the use of the press to repeat its echoes for a fortnight…It was the beginning of the end. Now and then some sublime madman strikes the hour of the centuries—and posterity wonders at the blindness which could not see in it the very hand of God, himself.”

Conditions finally forced the North to take a definite stand against the South. Outside of the cotton fields and the homes of the slave-holders, slavery had ceased to be of real value. Industries and the growth of cities demanded free labor. They demanded skilled workers, consumers for their market supplies, tenants for the landlords and a large class of the unemployed that would help reduce wages. These were the only things fought for in the civil war; the fate of the black slave was but an incidental issue.

To Abraham Lincoln, whose emancipatory greatness is really an historical myth, the liberation of the slave was merely of political importance. The State was much more to him than humanity; the security of the Union much more vital than the freedom of the Negro. The real opponents of slavery, men like Emerson, Thoreau, Lowell, Whittier, felt keenly the shame and outrage of the market in human bodies.

Wendell Phillips realized the double-faced and halfhearted methods of Lincoln and the administration at Washington; hence his unremitting attacks. “Liberty is our idea,” he once said, “and the government is trying to tread on eggs without breaking them.” He saw much deeper than the mere Abolitionist.

After slavery had been abolished, some erstwhile champions thought everything had been accomplished. Garrison, himself, withdrew from the scene of battle. Not so Phillips. He foresaw the things we are passing through to-day; he foresaw the corruption, the incompetency of the government, of the legislatures.

“Republican institutions will go down before money corporations. Rich men die; but banks are immortal, and railroad corporations never have any diseases. In the long run with legislatures, they are sure to win.”

Thus realizing that nothing can be gained through political channels, Phillips worked for a complete economic and social reconstruction of society. In an address to the workers he said: “Labor, the creator of wealth, is entitled to all it creates. Affirming this, we avow ourselves willing to accept the final results of a principal so radical, such as the overthrow of the whole profit-making system, the extinction of monopolies, the abolition of privileged classes, universal education or fraternity, and the final obliteration of the poverty of the masses.”

The workers of America should cherish the memory of Wendell Phillips. He towers high above his contemporaries. His name is still one of the beacon lights in the battle of great ideals.

Mother Earth was an anarchist magazine begin in 1906 and first edited by Emma Goldman in New York City. Alexander Berkman, became editor in 1907 after his release from prison until 1915.The journal has a history in the Free Society publication which had moved from San Francisco to New York City. Goldman was again editor in 1915 as the magazine was opposed to US entry into World War One and was closed down as a violator of the Espionage Act in 1917 with Goldman and Berkman, who had begun editing The Blast, being deported in 1919.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/mother-earth/Mother%20Earth%20v06n09%20%281911-11%29%20%28c2c%20Harvard%20DSR%29.pdf