This valuable look at the ‘six stages’ of the Red Army’s first four years from the semi-official ‘Soviet Russia’ also serves as an excellent short introduction to the Civil War.

‘The Red Army, A Historical Sketch of Four Years’ from Soviet Russia (New York). Vol. 7 No. 3. August 1, 1922.

BETWEEN the workers’ groups of the Red Guard in Petrograd, Moscow, the Donetz Basin, and in the Urals, in the months from March to May, 1917—to the regular divisions of the Red army of the present day there lies a path of hard experience, a path that finally led through victories and defeats to the termination of all internal and external fronts.

The Tsar’s army was overtaken by the same fate as all of the old Russia; the germs of disintegration were present in it long before the March Revolution. The peasantry, tired of the war, whose aims were unsympathetic to them, were already beginning in May and June 1916 to leave the trenches and to fraternize with and desert to the enemy. The revolution gave the final blow to the old army as an organization, which proceeded to crumble into the elements of which it was composed; the working class, however, which had inherited not only the governing power but also the questionable legacy of the old regime, found itself facing the task of creating a Red Army of workers and peasants, under the immediate pressure of the events of war. What is the history of the formation of this army? What are the results of the four years of revolution?

First Stage: from March to November

On February 24, 1917, strikes broke out in Petrograd; after short encounters with the police the troops went over to the people. The Red flag of revolution was raised over the palaces of the Tsar. But at this time the army, constituted, in the main, of peasants, which had so unanimously rebelled against its ‘Supreme Master’ had no revolutionary organization. The proletariat, which in reality was the driving power in this revolutionary blow, had no mass party; the only power of organization lay in the hands of the liberal bourgeoisie, to whom the power now passed. The general enthusiasm could, to be sure, smooth over all antagonisms for a time, but it could not eliminate the conditions making for class war; the formation of an armed force of its class was the chief task of the proletariat. The workers at Petrograd and other industrial centers already began to arm themselves on the day after the March Revolution, and to form the first troops of the workers’ guard. The protests of the government and of the Soviet still dominated by the Mensheviks can no longer hold up the course of events, and already the number of Red Guards has risen to ten thousand. When in the July days the Bolshevik party meets with defeat, this work suffers an interruption; but immediately after the Kornilov insurrection new workers’ battalions are formed, drills are held in the factories and works and in November the Red Guard, together with thе sailors, knock Krassnov and Kerensky on the head before the gates of Petrograd. Moscow and the provinces do not lag behind Petrograd; in the Urals there have been “Fighting Organizations of the People” since June, which have their own staff, subject to the party committee, and a firm basis is thus afforded for the passing of the power into the hands of the workers; Odessa and Moscow already have their Red Guard divisions in April. Parallel with this spontaneous movement there proceeds among the most advanced workers, beginning as early as March, 1917, the formation of a military organization of the Petrograd Committee of the Bolsheviki; communications have been established between all the regiments and detachments of the Petrograd garrison, as well as groups formed and revolutionary work among the masses begun. Early in May connections with the provinces and the front have been made and the Petrograd Military Commission becomes an All-Russian Center. The inability of the Kerensky Government to help the provinces, their treasonable agrarian policy and the desire of the masses for the termination of the war, create a situation in which the military organization has the greatest difficulty in preventing a premature uprising. In the July days after the unsuccessful Bolshevik revolt, the organization is destroyed. But the work of military preparation is continued and strengthened “illegally” and, simultaneously with the arming and grouping of the masses of the proletariat, as well as of the soldiers, a far-reaching, successful campaign is inaugurated at the front and also in the rear. November approaches. The Military Organization draws up the plan for an uprising, sends Commissars to the troops of the Petrograd garrison, with the aid of the latter takes possession of the stores of arms and munitions, and retains control of the insurrection.

The Red Guard, which arose everywhere during this first period of the organized armed proletariat, constituted a firm nucleus for the formation of the future Red Army. These troops were prepared, steeled in the fire of insurrections, for a hard task of battle.

Second Stage: From November to the Decree Creating the Red Army

The street fights in Petrograd and the still more bitter fights in Moscow, where the revolutionary garrison had to force the yunker troops out of the Kremlin and drag them one by one from houses in which they had taken refuge, ended with the victory of the revolution. Kerensky is able to recall only a few Cossack regiments from the front, under the command of General Krassnov. They are beaten by the Red Guards outside Petrograd in stubborn encounters. About the middle of November the headquarters are taken over by Comrade Krylenko and the counter-revolutionaries attempt to gain a foothold in the border regions. Kaledin gathers together regiments of officers in the Don region, Dutov occupies Orenburg, Petliura and Vinnichenko convoke the Ukrainian Rada, Semionov is in Siberia and Dovbor Musnitski in White Russia. The workers’ troops of the Red Guard rush into serious battles. Petersburg alone sends ten thousand men to the Don front; the Moscow and Ural workers are not outdone by those at Petersburg; revolutionary enthusiasm spurs these masses on to battle against the well organized enemy, whose forces consist frequently of officers only, and are led by famous military specialists. Poor training, weak discipline, and unorganized actions by small independent units— these peculiarities of the first stage of any popular army—were also characteristic of our first volunteer detachments. But these defects are neutralized by an iron will to conquer, by obstinacy, by the initiative of the fighters and by the support of the workers and peasants who join them in masses. After four months of combat our troops take Kiev (January, 1918), occupy Orenburg, defeat Kaledin’s forces at Taganrog, Alexeyev’s troops at Rostov, and Dovbor-Musnitski at Rogachev and Shlobin, and before the middle of April all the Ukraine, and the Don region, the Urals and Siberia are in the power of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Government. The latter now issues in rapid succession a number of decrees on peace, on the abolition of private property, as well as on the abolition of differences of rank and station; peace negotiations begin with Austria and Germany.

What has meanwhile been going on in the Tsar’s army?

The commanders for the most part, especially those of higher rank, were enemies of the workers’ revolution. The soldiers take demobilization in their own hands. The army was crippled from within, and no armed force of the revolutionary proletariat could be built up uроп it. Every soldier, whether he was a worker or a peasant, exhausted by the four years of warfare, necessarily had to be brought back to his accustomed work and to be remade in it before he could enter the new army that was to be built in the interests of the workers and peasants; the troops remaining at the front were completely disorganized; only a few Lettish regiments and detachments, in which the influence of the Bolsheviks was particularly strong, formed the sole strength remaining from the old army, upon which one could depend. The great masses were pouring back to their homes, and on their way destroyed the already feeble transportation facilities of the Republic.

On February 18 the Germans unexpectedly resume their advance and occupy Dvinsk; early in March they take Pskov and advance rapidly on Petersburg. The troops at the front flee without offering the least resistance. The Red Guard of the Petersburg proletariat in a single night calls into life whole regiments of workers. In the Smolny Institute a general staff is created. Twenty-four hours later armed trains and artillery proceed to the front, and after two days more the first cavalry division sets forth. “The Socialist fatherland is in danger,” Comrade Lenin announces in his proclamation. Red Petersburg receives its baptism of fire and forces the German advance to halt. An armistice is called, which leads to the peace of Brest-Litovsk. The entire situation of the Republic indicated the urgent necessity of creating a regular Red Army. The principle of universal military service was not in accord, however, with the attitude of the masses for the moment; as a provisional measure the principle of voluntary military service is applied and the local soviets display the greatest initiative. After this question has been elaborated in the All Russian Collegium for Organizing a Red Army, and after the fundamental points of the decree have been approved by the Soldiers’ Sections of the Third Congress of Soviets, the Council of People’s Commissars issued the Decree on the Organization of the Red Army, the army of the workers and peasants.

Third Stage: The Red Army and Voluntary Military Service (February to June, 1918)

The decree issued on February 23, 1918, includes the following statement:

“The new army is to be created from the conscious and organized elements of the working class. It is to be the foundation on which the standing army is to be succeeded in the near future by an arming of the entire population, and is to serve as a support for the approaching social revolution in Europe.”

With this decree the foundations are laid for a regular army of the proletariat: The workers and Red Guards constituted the kernel of the new formation, and gathered about them volunteers from among the working masses; thus there arose, simultaneously with the military operations, increasing more and more in extent, the first sections of the Red Army. At the same time local organs of supervision are formed, without which a transition to Universal Military Service would be impossible; furthermore, schools are established to prepare instructors for the workers’ and peasants’ army; old, experienced military specialists are engaged for the work. The All-Russian Executive Committee, on the basis of Comrade Trotsky’s report of April 22, sanctioned the decrees on the organization of War Commissariats in the villages, counties, provinces and cities, for the purpose of carrying out an efficient military training of the workers and peasants, and provided that the volunteers shall be obliged to undergo a training period of one-half year in the Red Army; at the same time the right of the troops to elect their officers is abolished and the number of instruction courses for army officers is increased. Finally, the Fifth Congress of Soviets establishes the necessary centralization of military organization, and war is declared against all independent military actions (June 5, 1918).

The formation of the Red Army continues to progress during the bloody struggle in Ukraine and on the Don. The bourgeoisie of the entire world hastens to the aid of its Russian brothers. Petlura, with the aid of German and Austrian regiments, takes possession of the Ukraine and Crimea; the vacillating policy of the irresponsible Petlura soon compels the Germans to replace him with Hetman Skoropadski. Krassnov, who had taken Kaledin’s place, occupies Rostov, Novorossisk and the entire Donets Basin. In Georgia and Baku, with the benevolent approval of the English garrison, the Mensheviks take charge of affairs. Our troops, as yet insufficiently supplemented by volunteers, wage a stubborn fight; the detachment of Comrades Sivers and Kividze—both die the death of heroes—acquire eternal fame in the fight against the Haidamaks* and Krasnov. The CzechoSlovak uprisings in Tambov and Kozlov are the links in the chain forged by the Entente to throttle the Russian workers’ revolution. The external and internal fronts require reserves and replacements. The principle of voluntary service does not suffice to fill these demands. The organs of control have now been organized, and officers are present in sufficient numbers, and therefore the first order of mobilization is issued on July 28, 1918. From the standpoint of the conduct of affairs during recent events, this entire period, up to the creation of the Revolutionary Council of War of the Republic, as well as of the single field staff attached to it, is characterized by a multifarious division of power, by duplication, by great powers in the hands of single groups, commanders-in-chief, heads of individual detachments and sections, etc. Already in February, at the time of the German advance, the Supreme Council of War had been formed as an administrative center of organization against the enemy in the West. It was concerned only with the events in the west. The creation of internal fronts and lines of defense made it imperative to create a new strategic body from the operative section of the staff of the Moscow War Area. If we add to this the staff of the Field Headquarters and finally also the All-Russian Supreme Staff, together with the still existing administration of the General Staff, the necessity for concentration becomes apparent, and this concentration was effected by the creation of the Revolutionary Council of War; this period is therefore characterized at the Center by a lack of unity and decision, and in the provinces by a burning initiative of the lower organs and the creation of more or less isolated sectors.

Fourth Stage: From the Czecho-Slovaks to Kolchak (July, 1918—March, 1919)

The Czecho-Slovak army, consisting of 30,000 men and eight batteries of three-inch guns, armored trains, and an air squadron, was to be transported to the French front by way of Vladivostok. The causes of the Czecho-Slovak insurrection were suf-activity [sic] of the French and English Governments in supporting this army, particularly its officers, is not open to dispute. On May 29 the Czecho-Slovaks took Penza; reinforced by all the counterrevolutionary forces of the Urals and Siberia, they then occupy Samara, Simbirsk, Ufa, and Yekaterinburg; thereafter their advance on Moscow begins. On July 28 they take Kazan, where our gold supply and great powder stores fall into their hands. At about the same time, Anglo-American detachments seize Murman and the White Sea region and send their flotillas up the Dvina. A number of insurrections in our rear, and the attempt of the Left Social-Revolutionaries, displeased by the Brest peace, to seize power in Moscow as well as Muraviev’s adventure at the front, put the republic in an extremely grave position. Connections between the front and rear were proven in this period to be quite firm. The country was transformed into a military camp. Conscriptions of workers are made in Moscow and Petrograd and later in the provinces, masses of non-commissioned officers and former officers formed the necessary kernel of the army; the mobilization of all party forces raised the morale of the Red Army men; the army loses the last vestiges of its improvised character and under the leadership of General Tukhachevsky (commander of the First Army), the first Red divisions march eastward. The recovery of the Volga and the Urals from the Whites was quickly accomplished, and on January 22, 1919 our troops united after the fall of Orenburg with the troops of Red Turkestan.

The mass mobilizations made it necessary to expand all the central provisioning organs and to create extraordinary military supply organs. The central provisioning administration, the national army administration, the national military supervision, the National Quartermaster’s Department and the central economic administration were reconstructed, placed in charge of a specialist and two commissars, and immediately began organizing a planful provisioning of the divisions in process of formation. The Supreme Military Inspection and the Bureau of Military Commissars develop the greatest energy; the former in the control and organization of military affairs in the localities, the latter in the distribution of the mobilized political workers and in guiding the activities of the commissars. The Chief Commissar for Military Schools speedily creates a system of short time courses. Hundreds, nay, thousands of workers, who passed through the fire of the first revolutionary struggle completed their military training in these schools. The first Red commanders appear on the Czecho-Slovak front as early as August 15; later they arrive at all the other fronts. In the severest moments that the Republic was obliged to undergo, they were the strongest prop and imbued our army with the necessary aggressiveness. After the East and South fronts had been formed, the Revolutionary sufficiently explained at the time, and we may be excused from dwelling further on them now. The Council of War of the Republic was established on September 2 under the chairmanship of Comrade Trotsky; all questions of national defense are centered in this institution. It organizes the northern and western front, liquidates countless centers of operation and consolidates their functions in the Field Staff of the Republic. The formation of new military units corresponding to the country’s resources, technology and transportation—in a word the entire military and peace work of the General Staff—is a heavy burden on the Republic’s Staff. In order to increase the performance of all the economic institutions of the country as much as possible and to strengthen its military forces, the Council of Labor and Defense was established under the chairmanship of Comrade Lenin late in October; on the fronts and in the armies appropriate revolutionary councils of war are created which contribute in great measure to the raising of the authority of the commanders and to the utilization of local resources for the army’s requirements. This internal organizing process in the army coincides with new successes of the Red arms. Toward the end of November, after the fall of William II, the German troops begin to evacuate our territory. Without encountering any resistance the Red Army occupies Esthonia, Latvia, Lithuania, White Russia and then also Ukraine. At the end of the period we are now considering there is at our disposal an army of more than one million men, of whom six hundred thousand constitute the fighting strength; in the provinces supplementary divisions were formed, but the following situation developed at the front: in the east, Kolchak, after dispersing the remnants of the Constituent Assembly, proclaims himself ruler of Russia (November 2, 1918). He does not limit himself to enrolling officers and Cossack detachments, but also conscripts the Siberian peasantry, obtains money and weapons from the Entente and prepares an offensive against Moscow for the Spring. In the south, Krassnov threatens Tsaritsin more than once during the Summer and Fall of 1918, finally pushes back our troops and threatens Voronezh; in the north, Chaikovsky, aided by the English troops, occupies Archangel, proceeds southward along the railroad line and the Dvina to give aid to the Czecho-Slovaks and occupies the northern shores of Lakes Onega and Ladoga; in the west the advance guard of the Entente, consisting of Letts, Esthonians and Poles, takes Riga and Narva, and later also Pinsk, Vilna and Baranovichi. The ring of the blockade tightens on all sides. The worst days of the Republic are at hand. Kolchak is the first to attempt to seize the power.

Fifth Stage: Kolchak and Denikin

In March, 1919, Kolchak advances rapidly to the Volga with 300,000 bayonets, 6,000 sabres, 700 guns and 2,500 machine guns. Soviet Russia’s peasantry very quickly grasped the significance of this offensive; behind Kolchak stood the big landed proprietor and behind him the tsarist uriadnikt; the Communist Party sends its best party workers to the Volga. “Аll to the East!” is the slogan of defense. All the available forces are placed at the disposal of the Commander on the East front, S.S. Kamenev; on April 25 (encounter at Buguruslan) begins the retreat of the shattered divisions of the “Supreme Ruler,” who had been recognized by all the nations of Europe. The Red volunteers have done much to bring about this result; they occupy Irkutsk, capture Kolchak and shoot him (February 7, 1920).

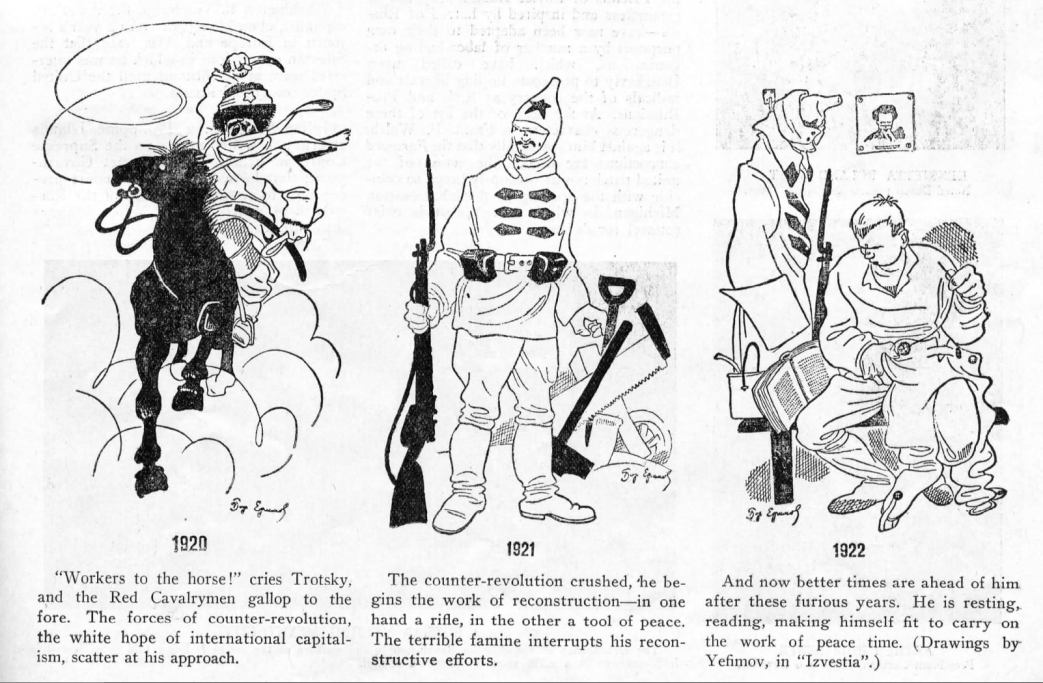

At the moment of the greatest exertions of our forces gaainst Kolchak, Denikin puts in his appearance as Krassnov’s successor. He is superior to us in his technical equipment, particularly artillery and tanks, presents from our former “Allies.” He has under him a well organized, powerful and able cavalry, is favored by the general situation (the attitude of the wealthy peasants of southeastern Russia), and thus he advances (beginning May, 1919) in order to unite as rapidly as possible with Kolchak on the Volga, and to take Moscow. Red Tsaritsin, on the flank of the southern front, was a reliable support for the: armies fighting Kolchak and Denikin; the latter encounters increasingly stubborn resistance as his advance proceeds. The mobilization in Ukraine and the attitude of a great many of the landed proprietors in the region create a new Red front in that region, which engages much of Denikin’s strength. Hoping to accelerate his advance, he determines to strike a blow at the heart of the Soviet State by means of a cavalry attack. Mamontov commits great depredations and temporarily occupies Kozlov and Tambov. “Proletarians to horse!” is Comrade Trotsky’s slogan in the formation of a great cavalry army, which is enthusiastically complied with. Already on October 19, Budenny’s armies crush Mamontov at Voronezh. On the 20th our troops take Orel. Budenny’s army advances into the center of the enemy’s forces, cuts them in two and forces them to retreat with enormous losses and without offering resistance. The eastern portion falls back on the White capitals, Rostov and Novorossik, the western to the Crimean peninsula; the intervention of Curzon and of the Entente fleet help General Wrangel, and we have had to pay heavily for not eliminating him at the proper moment.

The destruction of Yudenitch, near Petrogard, the elimination of the northern front and the absence of military operations on the Polish front, afford us a short breathing spell lasting until the spring of 1920. This period is characterized from the standpoint of organization by the great creative work of shock-troops, cavalry masses, the better training of the new formations, improvement in the command and technical equipment. From the operative standpoint Comrade Kamenev’s idea of a thoroughgoing liquidation of the fronts is fully carried out in this period.

Sixth Stage: Polish War, Wrangel, Internal Fronts

The fruits of the work of the Red Army on the internal labor front do not have time to mature. Supported in the most far-reaching manner by the Entente, the Poles, together with Petlura hasten to utilize this breathing spell by launching an offensive on Ukraine, hoping to find us too weak to fight; our army had only one-fourth the numerical strength of the Polish Army and had to retreat at the end of April and to relinquish Kiev, Zhitomir and Berdyansk.

“On to the fight with the Polish Pans” was the battle cry of the Government all through the Russian Republic; it found an echo everywhere in the country; the Communists set forth in masses, followed by tens of thousands of volunteers, while trusted regiments and divisions are fetched up from all the fronts. The Polish “Pans” receive their first blow on the northern section of the Polish front; our counter-offensive in Ukraine recaptures Kiev; then our armies pierce a line of fortified positions 110 versts long, advance, and occupy Minsk, Vilna, Molodechno, Bobruisk; Comrade Gay’s army corps on July 19 destroys powerful Polish detachments at Grodno, and advances to envelop Warsaw, taking possession of the Polish corridor. But the farther we advance the more stubborn becomes the Polish resistance; our rear does not keep pace with the front; on the other hand, the Polish “Pans” conduct a violent agitation among the peasant masses against our offensive and seek to awaken a national enthusiasm; they form fresh infantry and cavalry divisions and on August 14, under the walls of Warsaw, after a short and powerful drive, take the counter-offensive, penetrate our front in the north, throw the Gay Corps and the Fourth Army into German territory; and our troops are obliged to fall back to approximately the position of the present national boundary.

The conclusion of the Polish campaign permitted us to devote our best energies to fighting Wrangel, who had issued from Crimea through the isthmus in the spring. There was danger that the Donets Basin would be seized by him. By a series of crushing blows at Nikopol and Kakhovka, Wrangel’s forces are smashed and the powerful Red Army storms the impregnable fortifications of the isthmus of Perekop and the Sivash. Again the Soviet flag waved over Crimea.

The Red Army proved just as powerful in putting down mutineers and bandits. Kronstadt, the Makhno episode, the Tambov affair, the Savinkov and Petlura bands on the western boundary, the Finnish adventure in Karelia, all this is torn up by the roots and can no longer obstruct the economic reconstruction of the country.

During the four years of war the army, in spite of its organizational defects and its weak technique, threw back all the onslaughts of world imperialism. It has forced if not a formal recognition (which is also not far off), at least a de facto recognition of the Soviet Republic; it is a permanent inspiration for the world proletariat in its struggle against its oppressors.

Let us not take up the specifically tactical and strategic problems, but simply review briefly what has been said:

In spite of the far-reaching support of the Епtente the power of the White Guard generals disappears as soon as they begin to mobilize masses and draw them into their armies; as these armies were formed exclusively of officers, they disintegrated as soon as the latter were destroyed. The Red fronts in the rear of our enemies were one of the decisive factors in our victories. A second factor determining the outcome of the struggle was the manner in which the Communist Party was able to stimulate and increase further and further the enthusiasm in the ranks of the Red Guard masses. In this enthusiasm we must also look for the cause of the irresistible and rapid nature of our operations and the elemental force of our attack.

At present our army has been reestablished on a peace footing, reduced by one-third, and made into a frame for future operations. “When there are no fronts, danger is nevertheless not far off,” Comrade Trotsky said at the Ninth Soviet Congress. The present events sufficiently prove the truth of these words; the adventure in Karelia, the attack on the Far Eastern front, the disarmament farce in Washington, the cabinet crises in Western Europe, all these events are followed with interest by the Red Army. “Danger is at hand,” therefore there must always be a strong armed force ready to give battle at any moment.

While Soviet diplomacy is straining every means of securing a condition of peace, the army is not less tensely engaged in improving its quality.

The strengthening of the technical equipment, the growth of the Communist influence, the preparation and training of soldiers as well as commanders of Red divisions, the amelioration of our material situation—these are the tasks approached | by the Ninth All-Russian Congress of Soviets, and requiring solution to the greatest possible extent. ]t is a task that is clearly outlined, demanding great energy, great perseverance, great patience. A glorious past is behind us, but a still more glorious future awaits us.

Soviet Russia began in the summer of 1919, published by the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia and replaced The Weekly Bulletin of the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia. In lieu of an Embassy the Russian Soviet Government Bureau was the official voice of the Soviets in the US. Soviet Russia was published as the official organ of the RSGB until February 1922 when Soviet Russia became to the official organ of The Friends of Soviet Russia, becoming Soviet Russia Pictorial in 1923. There is no better US-published source for information on the Soviet state at this time, and includes official statements, articles by prominent Bolsheviks, data on the Soviet economy, weekly reports on the wars for survival the Soviets were engaged in, as well as efforts to in the US to lift the blockade and begin trade with the emerging Soviet Union.

PDF of full issue: (large file): https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/srp/v6-7-soviet-russia%20Jan-Dec%201922.pdf