A fantastic article, but not to be read over lunch. A worker in the know pulls the curtain back on the sausage making conditions of the meat packing industry and it is not pretty. How much have conditions in these plants changed since?

‘The Packing House Industry’ by A Worker from One Big Union Monthly. Vol. 2 No. 1. January, 1920.

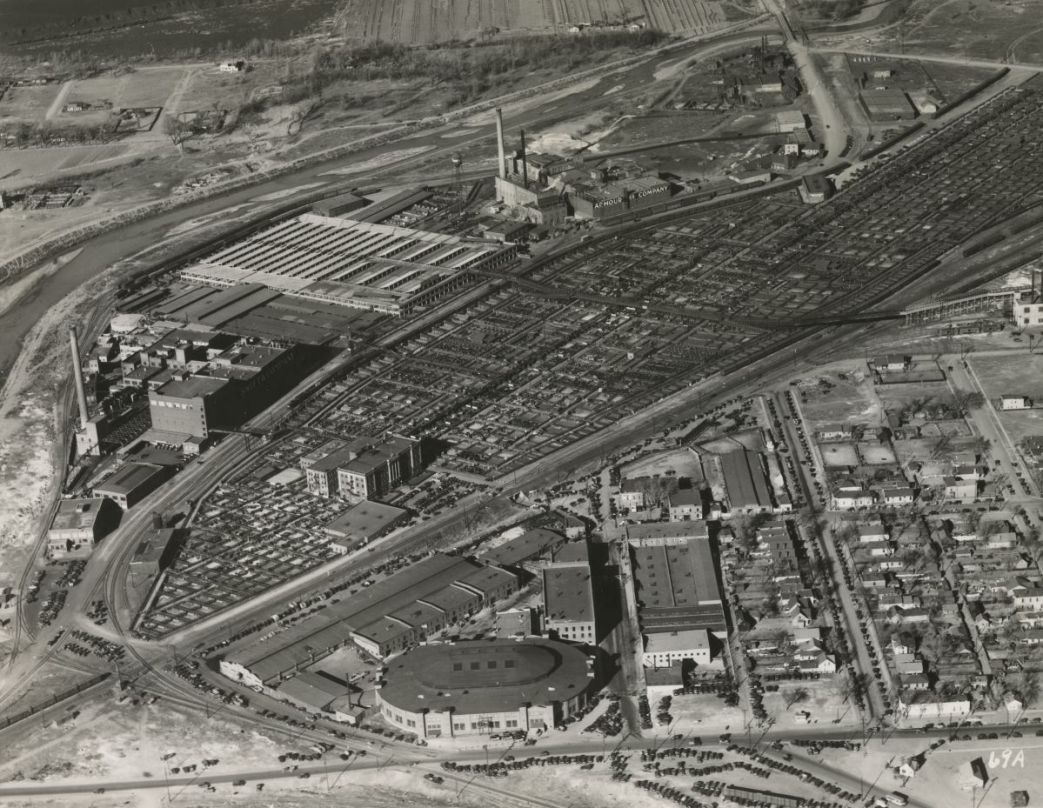

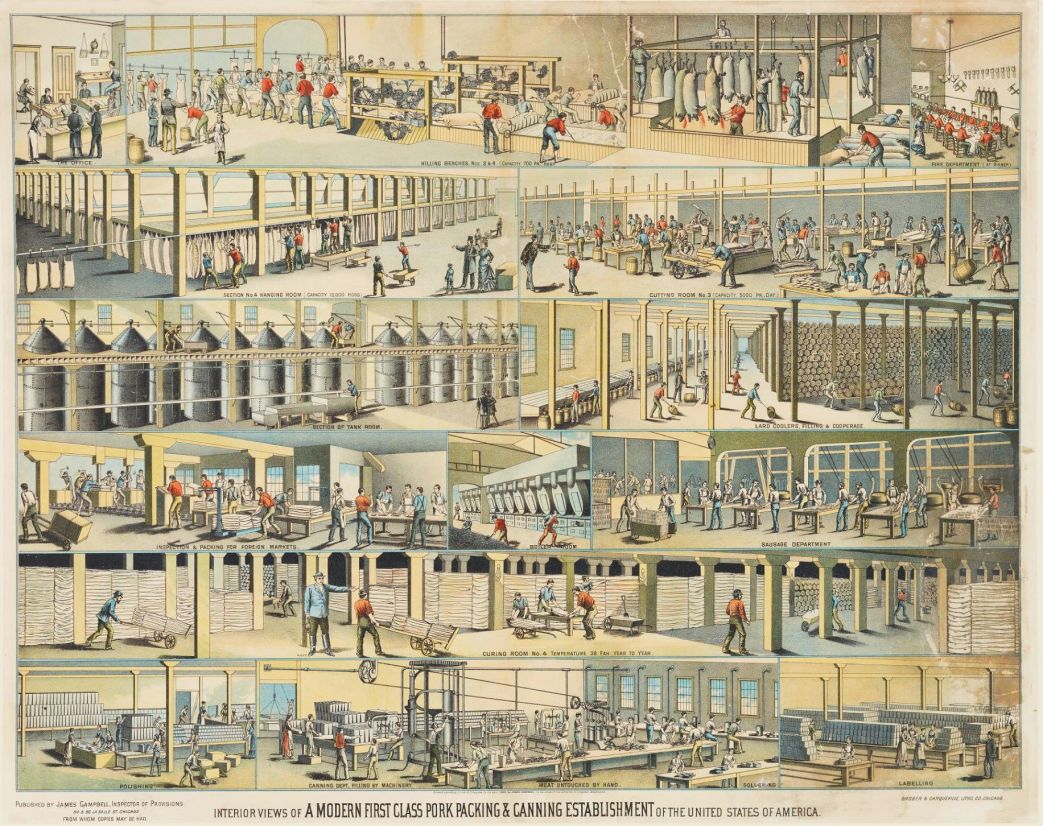

The meat packing industry as carried on in the great establishments of the country is one that deserves some attention from every worker, who at one time or other must depend on such sources for his food supply.

So the writer, in conjunction with some other workers like himself, will here endeavor to give a description in a brief way, and offer some suggestions that may prove helpful to those unacquainted with such matters, and perhaps furnish some information to those already engaged in the industry in one way or another.

As all such establishments handle Cattle, Sheep and Hogs, it will be necessary to take each separately, commencing with the Killing.

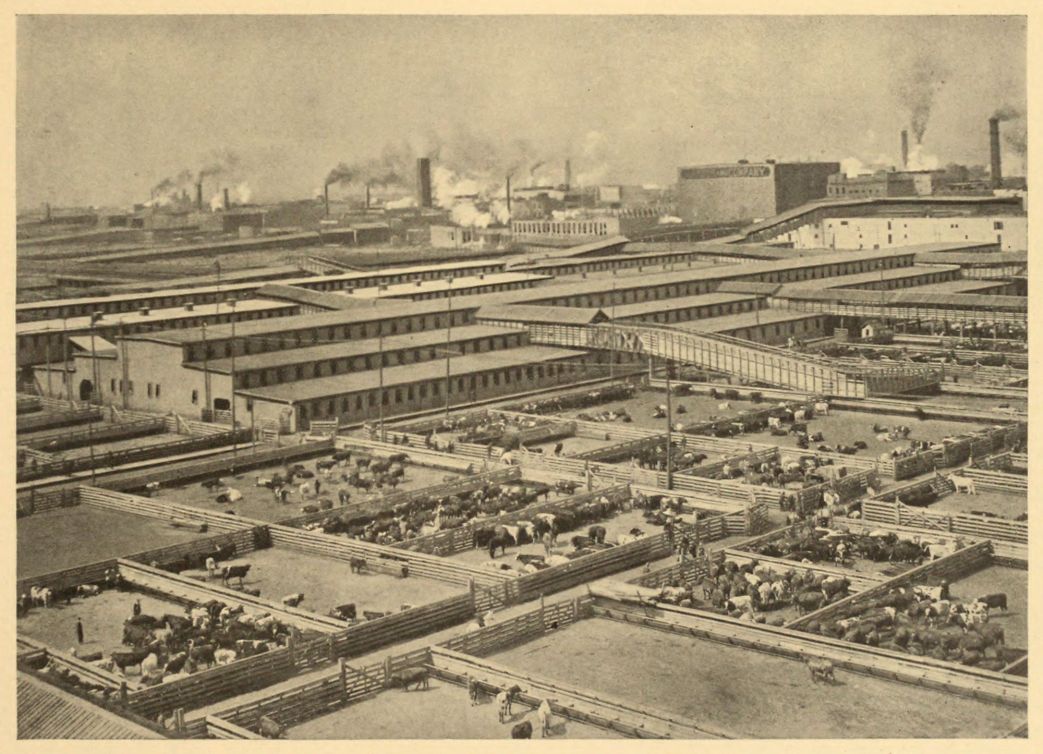

We begin with the Cattle, which are driven from the Stock Yards into pens convenient to the ‘Killing Beds,’ into which they are driven as many at a time as the ‘Beds’ will hold. When open the ‘Beds’ look like a long narrow alley. When the required number of animals have been driven in, this alley is found to be divided up into compartments, each compartment containing two animals. Then all is ready for the ‘Knocker,’ who, armed with a long-handled hammer, walks along a platform arranged for that purpose, smashing the skulls of the animals as he does so. As the animal falls in the pen, by an ingenious arrangement another worker is able to open the doors of the pen, the floor of which rises upward, so that the carcass is dumped out on the Killing floor. Here the carcass is hoisted up by a chain attached to the hind legs, when the head is skinned by a butcher whose work this is, after which the body is allowed to-drop down again, when the feet are skinned and the legs broken off at the knee and hock joints. Each function being performed by a different worker. Next the process of skinning begins, ‘the floorsman’ taking the sides, ‘the backer’ the back, ‘the felse cutter’ the hind quarter, and ‘the rumper’ the rump or butt as it is sometimes called. The carcass having been disemboweled, or ‘gutted.’ as it is usually called, is hoisted up and the ‘drop’ or neck is skinned by the ‘dropper’. The carcass is next put on a chain carrier, which pulls it along slowly. During its journey it is split into two parts by the ‘Splitters,’ after which, still on the chain, it is washed before being sent to the Coolers. The hide is sent to the Hide Cellar to be cured. The entrails being divided up, the Gut Shanty or casing department attends to the cleaning of the bowels and the curing of the same, preparatory to their being used in the manufacture of sausage, while in another place the fat from the same is washed before being sent to the Oleo department. Such scraps as are considered unsuitable for same are sent to the tank to be rendered into tallow. The liver, after being trimmed, is sent to the offal cooler, and the tripe or stomach having been cleaned, is either saved to be used as a food product or sent to the tank to be rendered into tallow.

The head, after being trimmed of meat, which is saved to be used in sausage, and after the tongue is taken out, is sent to the offal cooler. The jaw bone is broken off, the remaining part of the head being thrown into a crusher and there broken up before being sent to the glue tanks. The feet, with the hoofs pinched off, are also sent to the glue tanks, where Neatsfoot Oil is obtained from them. The horns, when there are any, are sent to the Bone House.

The conditions under which men work in this department are trying. The work is continuous and the clothes become wet and dirty, while in most cases an oil apron and rubber boots are necessary, which have to be provided by the worker at his own expense. And then there is the incessant noise made by the machinery and the animals about to be slaughtered.

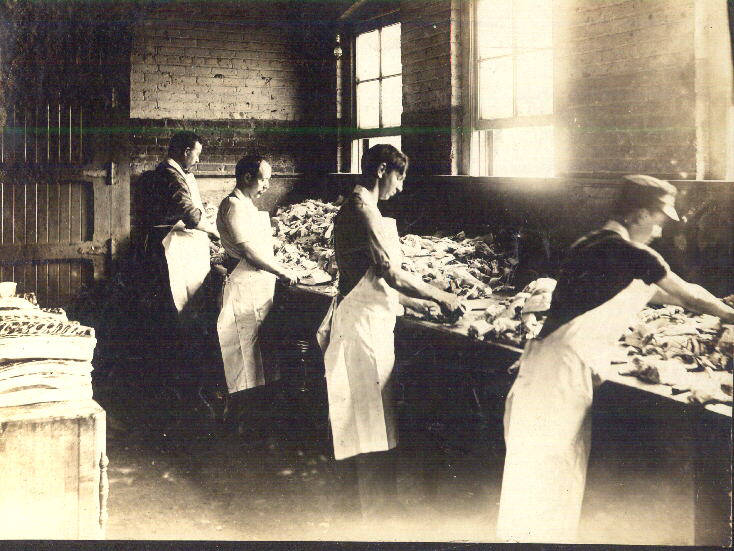

The beef sent to the coolers, is allowed to drain for some time in a place provided for the purpose, before being transferred to other coolers, the floors of which are covered with sawdust, and there it is allowed to remain until shipped or sent to the Cutting Room. The coolers are usually kept at a temperature of about 38 degrees Fahrenheit. In the casing room are a number of machines used in the cleaning of the casings as well as the fat from the same. Here the Bladders and Weasands are also taken care of, which are used after the same fashion as the casings. To work in this place an Oil Apron and Rubber Boots are necessary. The work in this place is disagreeable, and there is an uninviting smell about the place. Skill and experience are indispensable at the work. Here some women and girls are employed.

In the Beef Coolers, the quarters are kept in lots in the same order as they have been purchased and slaughtered; this is done by means of tags attached to the quarters when they are weighed before entering the cooler. In this way it is possible to trace each animal from the Stock Yards, where it has been purchased, down to the market where it is sold, the difference in price showing the profit or loss in the transaction.

The Offal, that is to say the food parts, comprising Livers, Kidneys, the Heart, Tripe, Cheek meat and other Trimmings, are kept in a cooler until they are shipped out or sent to the Freezer, to be held in Cold Storage for future use. Much of the Cheek meat and trimming is, however, used on the premises in manufacture of Sausage.

In the Hide Cellar, the hides are weighed up in lots after the same manner as the beef, in order to compute their value as part of the product of the animal in figuring out the gain or loss. After weighing they are salted in piles, known as ‘Packs,’ in building which some skill and muscular strength are required. In those ‘Packs,’ they are allowed to remain about thirty days, or longer, before being taken up for shipment to the Tannery, at least thirty days being considered necessary to allow the shrinkage to leave the hide.

The working conditions in the Hide Cellar are bad, there is an evil smell about the place, and the work is hard and continuous. As this is a part of the Packing House that is immune from Government Inspection, no attempt is made to clean the place, so dirt and stench are allowed to have full sway. Like the Fertilizer, this is one Department much avoided by men who know such places.

At the ‘Bone House.’ where the bones are only cooked long enough to take the grease out of them without softening the bone, which is sold for the manufacture of knife handles, buttons, etc., it is hot, very hot in fact, especially so in the summer time. It also is strenuously avoided by those who can do so. It is usually conducted as a part of the Tank House and Fertilizer Departments.

The fat sent to the Oleo department, after it has been washed, is dumped into a vat or tub of cold water, where it is allowed to chill before being hashed. After it has been ground up in the ‘Hasher,’ which is constructed something after the fashion of an ordinary meat grinder, it is taken to the ‘Kettles,’ where it is melted. The product so obtained is run into ‘Cedars,’ where it is allowed to chill to the point of softness necessary to allow it to be worked up in the Press Room, where the oleo oil is extracted from it. This oleo oil is used in the manufacture of ‘Oleomargarine,’ while the ‘Stearine’ is used at the ‘Lard Refinery’ in the manufacture of an article known as ‘Compound,’ while some of it is shipped out to be used in the manufacture of Soap.

At the ‘Cutting Room’ the sides of beef as they left the Killing Room are made into various Cuts. The better grades being made into Ribs, Loins, Younds and Chucks, in which shape they are shipped. The poorer grades are cut up into small pieces to be used for sausage or canning meat. However, when this is done, the beef hams are usually saved in this process, as well as the beef tenderloins. The Beef ham being divided into three parts: the Inside, Outside and Knuckle.

The working conditions in the Oleo are not agreeable or healthful. In the room where the Kettles are, in which the fat is melted, it is very hot, especially in the summer time, and often some worker is obliged to quit on account of the excessive heat. In the room where the fat is chilled, it is cool and more agreeable. The same may be said of the cellar where the Oleo oil and Stearine is stored. In the Cutting Room it is cool, the place being kept at about the same temperature as the Beef Coolers, 38 degrees Fahrenheit. In these places warm clothes and a white frock are necessary. The work though heavy and cumbersome is not continuous, except in the case of the Beef Boners, many of whom do Piece Work.

From the Beef we now will pass on to the Sheep Kill, this work being usually done on the same floor as the Beef Killing. The animals are driven into the Shackling Pen, where the shackles are attached to their hind limbs, then the shackle is attacked to a large revolving wheel, which carries them up until they reach a rail, on which they drop and slide down to the sticking pen. Here they are quickly dispatched by the ‘Sticker,’ after which they are skinned, gutted and washed, before being sent to the Sheep Cooler, which is merely a part of the Beef Cooler. The casings, such as are considered worth saving, are handled in about the same way as the Beef Casings. The fat, such as is not allowed to remain on the carcass, is sent to the Oleo Department, while the Sheep Pelt is sent to the Hide Cellar, where it is salted with fine salt and not with the coarse salt used for the cattle hides. The scraps and other refuse go to the Tank, except the head and legs, which find their way to the glue house, while to the Offal Cooler are sent the cheek meat, heart, lungs, liver and kidneys.

The working conditions in the Sheep Kill are about the same as in the Beef Kill, only that the work is not quite so heavy.

In the Hog killing department the number of animals slaughtered is usually in excess of that of either Cattle or Sheep, and by many considered of greater importance. This is especially true so far as work is concerned, as only a small portion of the carcass is used in a fresh state, which leaves the greater part to be cured and sometimes smoked before being shipped out for consumption.

In the killing process the animals are driven into the pen where they are shackled with chains designed for the purpose. This shackle being attached to a revolving wheel, the hog is hoisted up until it drops on a rail, which runs into the Sticking Pen, where the sticker sticks it in the throat, running his knife clear up to the heart. Having bled to death, or nearly so, it is pushed on to the scalding tub, which is filled with hot water and in which it is kept until the hair is sufficiently loosened on the skin to pull off easily. Then it is run through the scraping machine, which takes off most of the hair, what remains being scraped off with knives. The process of gutting and splitting performed, they are carried on an endless chain carrier to the hog coolers. Here they are usually allowed to remain from 36 to 48 hours before being sent to the Cutting Room. Hog Coolers are usually kept at a temperature of 52 degrees Fahrenheit. Most of the fat from the hogs is rendered into lard. The fat being stripped from the bowels is known as Caul fat and Ruffle fat, and there is also fat from the ‘Bung Cut’ and from the ‘Pizzles.’ The stomach of the hog is also used in the lard. The hog casings are cleaned and handled after about the same fashion as those of the cattle and sheep.

When the hogs have been the required time in the cooler, they are sent to the ‘Cutting Room,’ where they are cut up into the various cuts, which have been established as standards by the men engaged in this business. Such cuts are named about as follows: Hams, Shoulders, and Sides, which are again subdivided into pork loins, fat backs and bellies. In the lighter grades the side, after the pork loin is taken off, is split into a fat back and belly. When only the loin and ribs are removed, such sides are known as ‘Clears,’ or ‘Extra Clears.’ Where the rib is left in, they are known as ‘Extra Ribs.’ In some instances the heavy sides are allowed to go to cure without either the loin or ribs being removed, when they are known as ‘Rough Ribs,’ or ‘Hard Ribs.’ From the neck or jowl another small piece is saved, which is known as bean pork. All the fat from which the lean has been trimmed, that has accumulated in the cutting process, is sent to the tanks to be rendered into ‘Steam Lard,’ as distinguished from ‘Neutral Lard,’ which is obtained by rendering the leaf lard and sometimes the fat backs at a low temperature, which varies around about 120 degrees Fahrenheit.

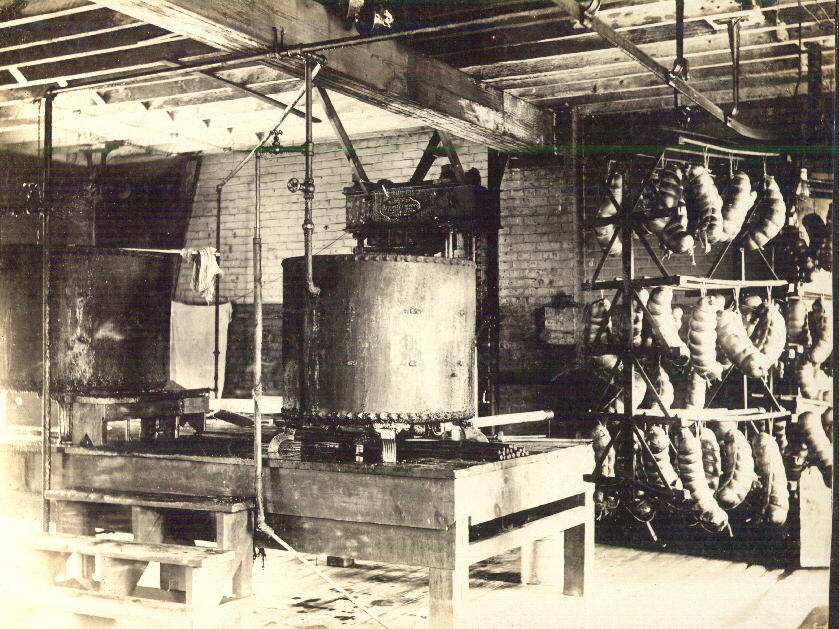

At the Tank Room are the Tanks, which are steel cylinders about six feet in diameter and varying in depth from 14 to 30 feet. Some establishments having the larger sizes and some the smaller. The tank capacity is usually estimated at a thousand pounds to a foot, when such computation becomes necessary. At the top, which usually comes about a foot above the floor, is an oval shaped opening by means of which the tank is filled. When this is done a manhole cover is allowed to pass into the opening by means of a chain. Then it is drawn back in its place, covering the hole from the inside. This done it is firmly bolted on by means of ‘grabs,’ so as to be air-tight, after which the steam is turned on and it begins to cook. Tanks are only supposed to be filled within three feet of the top, and are cooked from six to ten hours at a steam pressure, varying from 40 to 50 lbs., the length of time varying according to the matter to be cooked, and the steam pressure varying according to the size of the tank and the steam outlet or feed.

At the bottom the tank is closed by a valve, worked by a long rod having a wheel at the end, while underneath is a vat, usually an iron box-like affair, large enough to hold the contents of the tank. This is also furnished with an outlet leading to the press room.

When the contents of the tank are cooked, and the exhaust steam blown off, the head or manhole cover is taken off, when the rendered product, be it either Lard, Tallow or Grease, is drawn off through a valve, which is placed about the middle of the tank in its side. Such products, before mentioned, are allowed to run into iron containers, known as coolers.

In the press room the tankage which remains in the vat, after the tank water is allowed to run off, is allowed to run out on cloths spread over wooden plates; in this way the press is built up in layers, until it has reached the required height, when it is placed under a hydraulic press and subjected to pressure until most of the water and grease is forced out of it. Next the press is pulled down and the pressed tankage dumped into a carrier which carries it onto the ‘Dries,’ of which there are many different patterns. But when the tankage leave the ‘Drier’ it is dry and ground up into a coarse powder, in which state it is sent to the ‘Fertilizer.’ The blood of the various animals, which is saved after being steam cooked for a short time, is pressed and dried in the same manner as the tankage.

The tank water, which remained after the tank had been cooked and allowed to run out of the vat before the tankage was taken out, is held in a container from which it is pumped through vacuum pans, by which process a dark, thick fluid is obtained, which is known as ‘Stick.’ This is mixed in with the tankage in the drying process. At the Fertilizer, the tankage is sorted out into Hog tankage, Cattle Tankage, Meat Meal or Stock Food, and Steam Bone, which is obtained from the Glue Tanks. Each of these products on chemical analysis must show certain ingredients, and have to be mixed accordingly. The dried blood is either sold separate, or, being rich in Ammonia, is mixed in with the lower grades of tankage to make meat meal. When the tankage shows a too high percentage of Ammonia, Fullers Earth, the waste from the Lard Refinery, is usually added to it, and in some cases coal dust.

The working conditions in both the tank room and press room are of the worst kind. The heat is oppressive and an abominable stench pervades the place. This is true in all seasons, but especially in the summer time, when the temperature in those places keeps around 130 degrees. When the men there can only work in short spells, as it impossible to remain for any length of time in the place. In the Fertilizer, while the heat is absent, the dust and stench in the place make it even worse. As all fertilizer products have to be run through the mill, before being either filled into sacks or shipped out loose, the air in the place is usually so thick with dust, as to make it impossible to see more than a short distance. This dust is injurious to both the eyes and the lungs, so that those who are obliged to go there soon leave, or are obliged to do so on account of the work being injurious to health.

At the Lard Refinery, the lard which has been pumped there from the tank room, is treated to a refining process, which consists in mixing ‘Fuller’s Earth’ in with it, after which it is pumped through a filter in which the earth remains and the lard come out cleared of such impurities as this process can remove. Then when cooled to a point where it is soft and thick, it has a fine white color. In this state it is filled into containers of various sizes, ranging from a five pound can to a tierce holding about four hundred pounds, when it is ready for shipment. At this same department is also made an article which resembles lard in appearance, known as ‘Compound,’ which has before been referred to in connection with beef products.

In the way of curing meats there are two distinct processes known as ‘sweet’ and ‘dry salt’ respectively. In the sweet pickle, brown sugar, granulated, white sugar and molasses are used in the brine in which the meat is cured; hence the use of the word ’sweet.’ In this department the smaller meat cuts are cured, such as hams, shoulders, bellies and Picnic or California Hams. During the curing process the meat is kept in large wooden containers known as ‘Vats,’ where it is kept for a period ranging from three to nine weeks. During this time it is ‘overhauled’ three times, except in case of the lighter cuts, such as bellies, when the operation is performed only twice, as they cure in a short time. The ‘overhauling’ process, consists in transferring the meat from one vat to another, an empty one being placed in the row for this purpose. When cured, the meat is either shipped out in this condition or sent to the smoke house to be smoked before shipment. In the ‘dry salt,’ the heavier meat cuts, namely the side cuts before alluded to, as well as some heavy shoulders and heavy bellies, are put. Here the meat is rubbed over and sprinkled with salt and is then piled on the floor, until it reaches up to a height of some six feet or more. In this condition it is allowed to remain until it is overhauled or shipped out. The overhauling process consists in pulling down the pile and transferring it to another pile in reverse order, so that the pieces that were on top come in the bottom. In the first instance this is usually done after the meat has been salted about a week or ten days, and after that at irregular intervals. In both sweet pickle and dry salt all the heavy meat cuts are usually pumped up with a strong brine prepared for this purpose. Also this is frequently done when the meat is being overhauled.

The pork cuts which are not sent to cure, such as pork loins, pork butts, skinned shoulders and spare ribs, are either shipped out in a fresh state or sent to the freezer, where they are frozen and kept in storage.

As to beef, only a small portion is sent to cure, most of which is what is known as canning meat, beef hams and plate beef. The canning meat consists of small pieces of meat which have been cut from the bones or large pieces, which cannot be used otherwise, and so are cut up for this purpose. Brown sugar is used in curing canning meat, while granulated sugar is used for beef hams. In curing plate beef, sugar is not used.

Meat that is suitable only for sausage, which has not been used in a fresh state, is put to cure. This includes hearts, livers and kidneys, such work being usually done under the supervision of the sausage department.

At the Packing House, it rarely happens that any meat, except trimmings of one kind or another, are used in the manufacture of sausage, there usually being a sufficiency of the same for this purpose. Such meat, of course, is of much less value than regular cuts, but when worked up into sausage, it becomes much more valuable than those same cuts. This is partly owing to the fact that corn meal is mixed in with it. This, however, is shown on the labels under the name of ‘Cereal.’ Also a quantity of water is added to it. The amount of ‘Cereal’ varies according to the kind of sausage made, and there are many kinds. The amount of water added to sausage meat in the process of manufacture varies from ten all the way to as high as forty per cent. Nothing is allowed to appear on the labels or containers to indicate its presence. There are of course some grades of sausage in which water is not used, especially in ‘Summer Sausage’ and a few other high priced grades. But that it is one of the most profitable branches of the meat trade is fully shown by the number of outside concerns that engage exclusively in it.

In the Packing House the Dressing Room accommodation provided is simply disgraceful. The writer, from all he has seen and from what he could learn, must say that there are few if any such places that are not overcrowded, so that the men have to take turns in getting a seat to change clothes. In many places there is not even standing room for the number of persons required to use the place. But worst of all are the lockers, in which the men have to keep their clothes. They are made in sets of about six compartments in one piece, having an iron frame, the sides being composed of wire netting. The compartments, which two men are obliged to use for their clothes, measure in dimension about fourteen inches square and stand about forty inches in height. Even though the worker as a rule has not many clothes (and from the accommodation provided by his master, it is evident he thinks he should not have), it is easy to see that those miniature compartments are usually crowded. This, however, is not the only grievance, as, should a worker have some good clothes, he is obliged to put them into the same locker, where he has to keep his dirty, foul smelling clothes, and there they very soon become contaminated with the same bad smell, so that he himself and his apparel become a nuisance when he goes in a public place. Worse still is it for the unfortunate worker whose clothes become wet at this task, and this is especially true of workers in the ‘sweet pickle’ and the ‘dry salt.’ Having to wear extra clothing in those places in which they work, their wet clothing cannot dry in the miserable lockers, even when heat is provided in the dressing room, which is not often the case.

The Labor Unions have endeavored to remedy this and some other evils, but apparently without effect, as nothing has been done so far, and at present the prospects for any improvement are very doubtful.

What the Packing House needs at present, and needs badly, is the ‘One Big Union,’ and it is coming, because if any results are to be gained, it must come.

In so far as the running of the plants by the men is concerned, if it were to happen tomorrow, the change would hardly be noticeable, as the men to a great extent are doing it already, and for the most part are well aware of the fact, as the foremen and other supervisors placed over them have but little experience, and in some cases none at all. Of course, there are some exceptions, but those are not many. From the point of view of educating the worker, nothing could be better in order to show him his own importance, than to place in authority over him another man who does not know what he is doing. This is especially true where skill and experience are required, something which is indispensable in a great many cases.

As a direct result of such incompetency, there is much waste in the handling of the various products as well as in other material and supplies. An instance of this is the thousands of pounds of meat and meat food products annually condemned by Government Inspectors. A change in system and arrangement would easily save most of this, which can only be done by giving the workers a greater share in the management and in the profits of their labor. In doing this, more men would be employed for shorter hours and a more efficient and economical system would at once arise. The masters knowing this are at present seeking to introduce a profit sharing plan, while of course having only their own interests in mind.

Assuming that the Cattle, Sheep and Hogs would continue to be obtained from the farmers, which of course would probably be the case, as there would be no other way to dispose of them, the next important problem would be the distribution of the food products. The capitalists, however, have already provided for this in having established branch houses «in all the large cities, and have records of the amount of such foods used from day to day, so as to prevent anything like a large surplus accumulating at any particular point. The same course could be followed, provided the transportation facilities would be available. On this everything would depend.

Outside of labor power, the Packing House needs coal and water in large quantities, so that their operation depends much on the coal miner. As for water, this is usually obtained from the city water supply of the cities in which the plants are located, though in some instances the plants have their own water system, which usually consists in a number of wells operated by either steam or electric power, which feed into a reservoir, from which the water supply is obtained. In the way of other supplies, a large quantity of lumber is needed for making boxes used for packing, wrapping paper and stationery as well as cordage of various kinds are also indispensable. Also salt, both coarse and fine, is largely used. Cooperage in the way of tierces and barrels of various kinds are also much used, being brought from factories outside and refinished by the coopers of the plant. Hardware and other mechanical supplies are also much used in repair and new work by mechanics, of which every plant has a number.

It will therefore be necessary for the Packing House worker to get in touch with the various workers on the outside, with whom contact will be necessary in order to obtain such articles as may be needed to carry on the business. This ought not to present any serious difficulty, as a mutual exchange on the basis of food supplies will not meet with opposition, provided that such supplies are available. But even the dullest among the workers usually has foresight enough to look ahead in the way of getting something to eat. This he has always done, unless prevented, and will continue to do so. As a last word let us get on the job and learn all we can, no matter when it may be necessary to use our knowledge. Any person wishing further information on the subject will be answered by the writer through the magazine columns, that is if the editor is willing.

Editors Note:—A handbook covering the Packing House Industry is an urgent necessity. While the individual worker, as the writer points out, may know exactly what to do in his particular place, it is absolutely necessary that this group of workers should collectively have a complete understanding of the whole industry as well as its relations to other industries and society in general. Such knowledge is indispensable in order to enable them to take over the whole industry and run it with greatest possible efficiency through their union.

Each establishment should be organized as a branch of the Food stuffs Workers’ Industrial Union, and each branch should organize in such a manner that the workers may be able to operate and run it in conjunction with the other branches when that time comes.

What these workers now are familiar with is mainly the technical side of the work. Of the administration of the industry they know little or nothing. This they must learn in order to enable themselves to take the responsibility of feeding mankind. There are at present no books on this subject. It remains for the I.W.W. to do it.

One Big Union Monthly was a magazine published in Chicago by the General Executive Board of the Industrial Workers of the World from 1919 until 1938, with a break from February, 1921 until September, 1926 when Industrial Pioneer was produced. OBU was a large format, magazine publication with heavy use of images, cartoons and photos. OBU carried news, analysis, poetry, and art as well as I.W.W. local and national reports.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/sim_one-big-union-monthly_1920-01_2_1/sim_one-big-union-monthly_1920-01_2_1.pdf