Early Marxist literary critic, the always interesting Marcus Hitch compares the persons and worlds of John Milton, and his Paradise Lost, with Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and his Faust, in the essay from a larger work on Goethe’s Faust.

‘Goethe and Milton’ by Marcus Hitch from Goethe’s Faust: A Fragment of Socialist Criticism. Charles H. Kerr Publishers, Chicago. 1908.

Goethe and Milton were separated by about one hundred and fifty years. It is worth while with a few rough strokes to compare these two men. Both were born in important cities and belonged to the well-to-do burgher class. Goethe’s father was a councilor, Milton’s a scrivener, combining probably the work of an attorney and conveyancer. Both were most carefully educated in the classics from early youth, finished the University and continued their studies for a considerable time thereafter. Both were students of Italian literature and visited Italy. Milton did this earlier in life, when his youthful enthusiasm led him even to vie with the native poets in their own tongue. Goethe made the journey later in life and devoted more attention to matters of art. Milton was the more intellectual; his mind (and we had almost said his body) was scholarly and classical of the purest type and his whole education tended to develop this character. Aside from music, in which he was proficient, he does not seem to have cultivated the arts, nor the sciences either. In his Paradise Lost, perhaps for poetic reasons, he still uses the Ptolemaic system of astronomy. Goethe’s range of studies was wider and embraced all the arts and sciences. Also the influence of French literature was much greater on Goethe than on Milton, as was to be expected, for reasons that are apparent. Both exhibited in early life great talent for dramatic writing. Although Milton’s trend in this direction was checked by external circumstances, his ability was unquestioned. Goethe was able to give full swing to his genius in this field.

In their marriage relations both were unfortunate. Milton, having experienced the domestic inferno, was too honest and courageous to tamely submit in silence, as many do, but straightway wrote his treatises on Divorce, proved the righteousness of divorce for incompatibility by the infallible authority of the Bible and set the ideal of domestic liberty on a par with religious and civil liberty. Finding polygamy justified by the Old Testament, he justified polygamy. He did not assume to be wiser than the God of Abraham. Goethe, having entered into an unfortunate domestic relation, bore it to the end with a fortitude and constancy which commands our profoundest respect. He wrote his Elective Affinities, which, contrary to popular opinion, teaches that marriage is or should be indissoluble upon any ground whatever. On the marriage question we should say that the supposed Epicurean stands on as high a plane of morality as the pretentious Christian, if not higher.

Milton’s supposed puritanism is as distasteful to the Germans as Goethe’s supposed libertinism is to the English, and prejudice in both cases has no doubt prevented many from appreciating these two men. Goethe’s Teutonic physique and exuberant spirits and vitality would make poets like Spenser and Milton seem to him squeamish, cold and self-righteous. The hearty, lusty humanness and animalism of Chaucer, Shakespeare and Byron was more congenial to the poet who could write the scene in Auerbach’s Cellar, a feat which we venture to say would have been utterly impossible for Milton to accomplish. He could be coarse when necessary for serious purposes, as he was in his reply to Salmasius, but not out of mere frivolity. In order to contrast Milton’s daintiness with the revelry of the wine cellar, let us quote here his sonnet giving his idea of conviviality: —

“Lawrence, of virtuous father virtuous son,

Now that the fields are dank and ways are mire,

Where shall we sometimes meet, and by the fire

Help waste a sullen day, what may be won

From the hard season gaining? Time will run

On smoother, till Favonius re-inspire

The frozen earth, and clothe in fresh attire

The lilly and rose, that neither sowed nor spun.

What neat repast shall feast us, light and choice.

Of Attic taste, with wine, whence we may rise

To hear the lute well touched, or artful voice

Warble immortal notes and Tuscan air?

He who of those delights can judge and spare

To interpose them oft, is not unwise.”

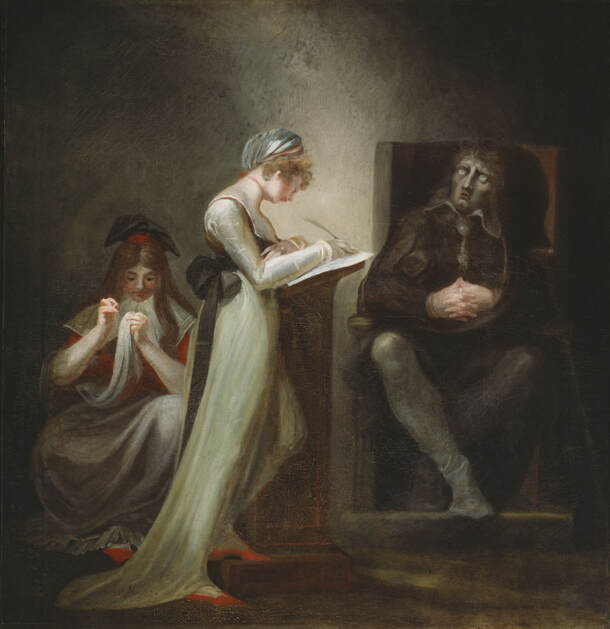

Goethe’s inner life was full of storm and stress. Milton, so far as we can judge, never had to go through the fierce struggle for self-mastery which Goethe has so vividly pictured in Faust’s advances to Gretchen. and he was consequently spared the humiliation of such a fall as Faust suffered. In Milton’s case continence was no great virtue. He never realized in his own experience the full meaning of the truth that the man who stops in a downward course is greater than he who successfully resists the first temptation.

Each of these men occupied an official position in the government and lived through a period of great political upheaval. Goethe’s position was insignificant and needs no further notice. Milton, hearing the rumblings of the approaching conflict while in Italy, hastened home from his travels, dropped his cherished studies and his poetry and threw himself with absolute devotion on the side of what was then progress. He was ill-fitted for such rough and tumble strife, a thing which many of us make into an excuse for shirking duty at the present time. Even when using his pen in support of the commonwealth as Cromwell’s Foreign Secretary, he felt as though he were working only with his left hand, as he expresses it. Yet with this left hand he wrote the Defense of the English People and completely demolished Salmasihs and the whole crew of royal apologists.

Read his stern protest in Cromwell’s name to the Prince of Piedmont against the massacre of the Waldenses and warning against any further attem.pt to coerce them on account of their religion (which was heeded); compare this vigorous action with the passive attitude of the so-called American Commonwealth towards the massacres that have been going on now for years in Russia and see how faint censure here amounts to practical approval of those atrocities; see how our milksop statesmen and presidential candidates, traveling in Russia, hobnob with the authorities who are responsible for these things ; and then figure out if you can, how long it will take at this rate of backsliding for bourgeois democracy to reach the goal of Liberty.

For twenty years Milton fought the good fight, and after working himself blind and seeing his cause temporarily defeated, he withdrew to devote himself again to the Muses. Another in his place might easily have given up hope and lent his genius to the victorious reaction. But not Milton. Although he had got a little ahead of the procession, it was not for him to go back to the mass. He looked forward to the time when the body of the procession would catch up with him and appreciate his work. His last piece, the Grecian-modeled drama Sampson Agonistes, breathes a spirit of defiance rather than defeat. Though unsuccessful he had made no mistake.

What Goethe would have done had he been drawn into the vortex of a first rate social war such as the English Commonwealth, the French Revolution or the struggle now going on in Russia, it is impossible to say. He was never put to the test. As a spectator beyond the border he witnessed the French Revolution. The enlightenment which took place in the intellectual world preceding that outbreak had its influence on him. Its restless and defiant spirit is reflected in the character of Faust in Part I. But in later years when the popular cause had apparently failed, Goethe seems to have had no higher political ideal than a benevolent paternalism. His moral courage and convictions cannot be questioned; but his environment was unpropitious and his mission seemed to lie in another direction. It was the ambitious scope of Part II of Faust, intended to cover the whole social activity of man, which forced Goethe to venture to some extent on political ground, with indifferent success, as we have tried to show.

Goethe could have learned something from Milton about politics and also about cultivating the sense of duty and educating the conscience, instead of merely running through the world, as Faust boasts to Care. But in some things Goethe shows a long advance over Milton: — he had freed himself not only from scholastic austerity and the slavish imitation of classical literature, but also from dogmatic theology. For Milton the Bible was the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth; although he did pretty much as he pleased, his argumentative skill was always equal to the task of reconciling his acts and views with the Bible. Goethe too was familiar with the Bible, but in his day the influence of the dogmatic-metaphysical was on the wane and the effect of the evolutionary method was already noticeable. Goethe’s combination of the romantic and the classical, of the spirit and the flesh, gave him broader human sympathies. If it was the merit of the Greeks to have first represented the gods in human form instead of in the earlier forms of animals and monsters, we may say it was Goethe’s merit to have drawn both Lord and Devil from the far away regions in which they dwelt in the strained imaginations of Dante and Milton, and brought them down to earth to talk and act like human beings. /Milton sings of woman’s fall as the cause of all our woe, and his estimation of woman is strictly patriarchal. She is an inferior being. The race ruined by her must be redeemed by a male, the first-born of God.

Goethe’s story is the reverse of this. He shows us a man, and a strong one at that, yielding to the devil and his salvation by a daughter of Eve instead of by the son of God. And the woman makes the vicarious atonement too; she so loved the man that she not only gave up all for him in her life time, but died on the block that the requirements of “justice” might be fulfilled to the strict letter of the law. It was this that made her prayers to the mater gloriosa, the Queen of Heaven, effectual to save Faust’s soul.

The duality of sex seems to be as great a stumbling block in religion as the duality of mind and matter formerly was in philosophy. This difficulty has now been overcome in philosophy, by the work of Dietzgen and others, not by denying to one the right of existence or by sacrificing one to the other or trying unnaturally to force one into the category of the other; but by referring both mind and matter to a genus high enough to include both, viz. the unifying Infinity or infinite Universe. Nature is large enough to contain and unify all differences and apparent opposites. The next great poet who attempts anything on these lines will have to reconcile this duality of sex. The abolition or reconciliation of economic classes will go far towards clearing the way for the reconciliation of the sexes ; and we suspect that instead of being compelled to resort to the expedient of having one sex save the other by the sacrifice and death of the innocent to atone for the guilty, our future poet will be able to find a way by which the whole race can co-operate in harmony for the salvation of all its members of both sexes without the unnecessary sacrifice of any.

Goethe had no use for Christianity. Although Jesus was human enough to be attractive, yet in his genuine, original character he was too radical and plebeian for Goethe’s purposes ; and in the distorted and monstrous character which has been foisted upon him by the political hierarchy called the Church, putting the seal of heaven’s approval on every form of oppression, he is more like Mephistopheles than Jesus, Hence Goethe had to get along without him.

Milton’s theme is now dead. Paradise Lost was once quite generally used as a reading and parsing book in schools ; but that day is past. Goethe’s theme however is still fresh and will continue to occupy reflecting minds until the abolition of class society has enabled mankind to eat the forbidden fruit of Knowledge and has revealed the mystery of human “government” and of Plato’s “wisdom” and at the same time revealed the mystery of so-called Good and Evil.

Goethe’s Faust: A Fragment of Socialist Criticism by Marcus Hitch. Charles H. Kerr Publishers, Chicago. 1908.

Contents: Goethe’s Faust, An Outline of Part One, An Outline of Part Two, Comments, The Model Colony Freedom, The Gretchen Tragedy, Goethe and Milton. 127 pages.

The Charles H Kerr publishing house was responsible for some of the earliest translations and editions of Marx, Engels, and other leaders of the socialist movement in the United States. Publisher of the Socialist Party aligned International Socialist Review, the Charles H Kerr Co. was an exponent of the Party’s left wing and the most important left publisher of the pre-Communist US workers movement.

PDF of original book: https://archive.org/download/goethesfaustfrag00hitc/goethesfaustfrag00hitc.pdf