Less well-known than the Chicago and later Kansas City Defendants, the ‘Silent Defenders.’ The Sacramento trial of forty-plus I.W.W. members for criminal syndicalism saw all the wobblies refuse to testify or be represented by counsel in the brazenly unfair proceedings. All were found guilty and sentenced from one to ten years. Many of them were among the last politicals to be released in the Christmas Pardon of 1923 Legendary labor journalist Art Shields looks in on their journey since the trial.

‘For the Silent Defenders’ by Arthur Shields from the Liberator. Vol. 5 No. 9. September, 1922.

JACK RANDOLPH was in jail in Portland, Oregon, as many a wobbly organizer had been before, when he was suddenly taken out and arraigned before the local magistrate on a fresh count. “Charged with obstructing traffic and inciting to riot,” read the clerk. Five and twenty deputy sheriffs swore that a violent revolutionary speech was made by Randolph in the middle of the sacred highway.

“Why, Your Honor,” gasped Randolph, “I was in jail at that time.”

“Sure he was,” corroborated the police sergeant, fetching in the police record of his previous incarceration. The man in dark robes swung the evidence on the scales and appraised the balance in the light of the needs of the best people of Portland.

“Five days!” he said coldly. “You need not think that a police blotter is going to outweigh the testimony of twenty five officers of the law. These deputy sheriffs are public officials. They are paid to speak the truth. It is not to their interest to distort the truth.” And Randolph was led back to the jail.

In the cell Jack discovered an old copy of Pilgrim’s Progress which the Salvation Army had sent around for the good of his soul. It proved surprisingly delightful, for his recent experiences had given him the background to appreciate one of the choicest scenes in the old allegory. The trial of Christian and Faithful before My Lord Hategood in the courts of Vanity Fair was a nice reflection of the court scenes of Portland. Jack has told me also that his adventures with the law gave him a further insight into Shakespeare, and that he now knows the critics are all wrong when they give serious heed to the assumption that old man Lear went a little “off.” So far as he is concerned, he says, when the wandering king howled out “Which is the justice, which the thief?” he was just talking sense.

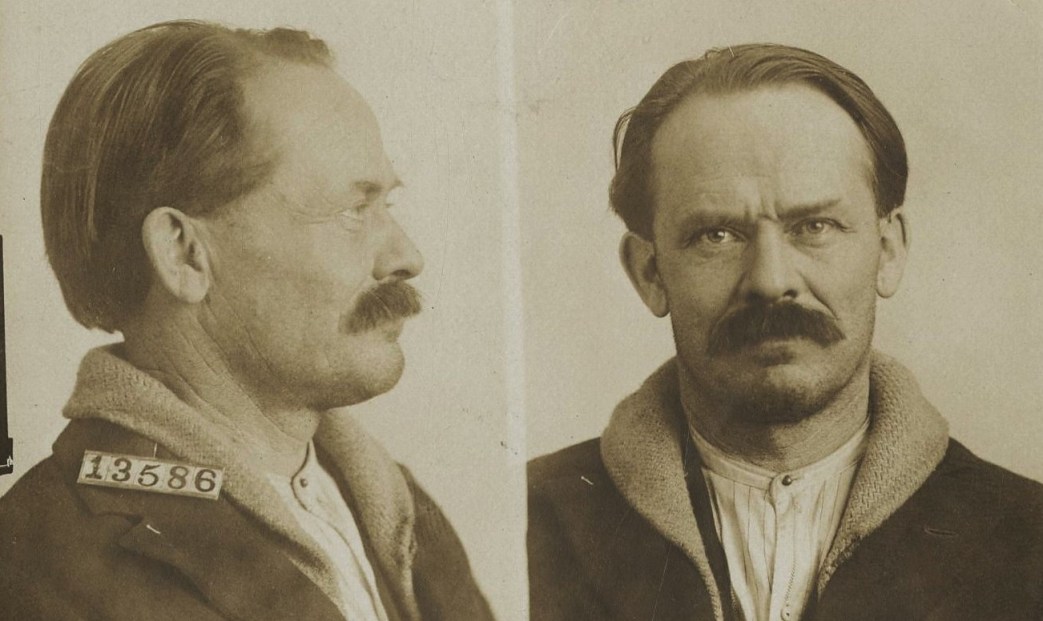

Pacific Coast judges have been generous in their schooling of the wobblies in the ways and wherefores of legal procedure, from the earliest days on, but the fact is that this tutelage was still in its elementary stages in 1913, when Randolph saw the testimony of a police blotter outweighed by the five and twenty deputies. It was not actually till the New Freedom reached its climax in 1917 that their higher education began, and so well did the judicial instructors do their work that in the course of the next two years a strong movement against participating in legal defense gained ground among radical unionists. This sentiment found its first and only large scale expression in the famous Silent Defense of forty three members of the I.W.W. at Sacramento in the early part of 1919.

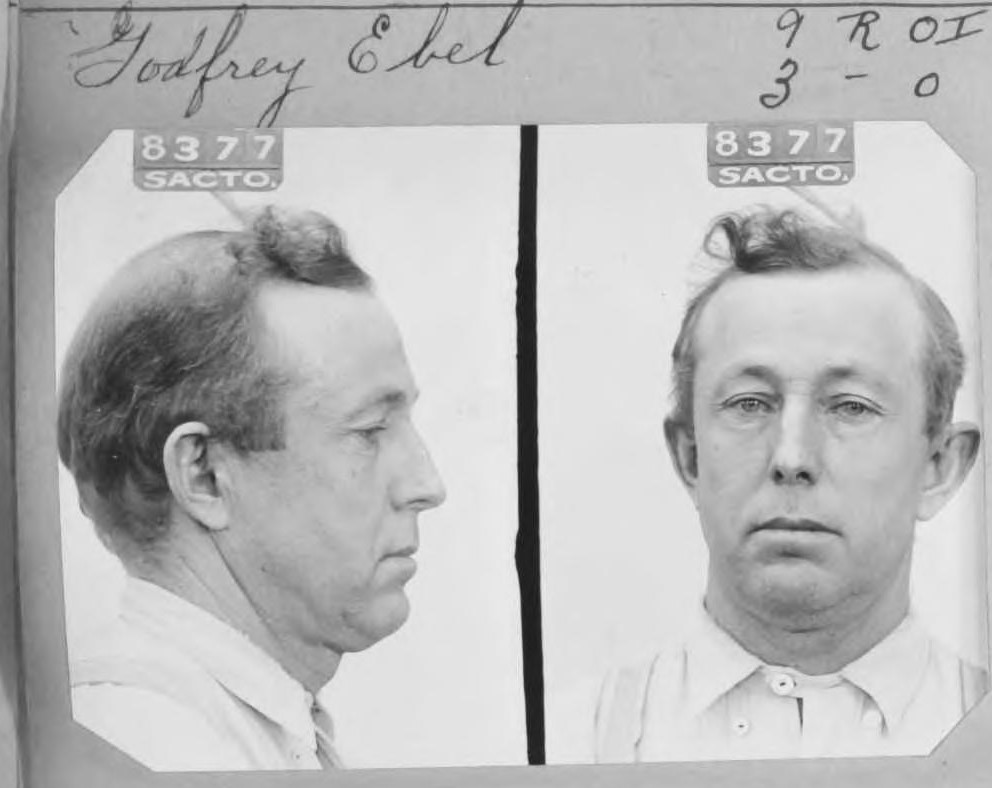

The Sacramento Silent Defense was a natural outcome of the disillusioning experiences the boys had been going through. Perhaps they still kept one illusion-that the working class would rise against such flagrant persecution of members of its class. And it is open to argument as to whether they would not have eventually gained by using conventional defense methods and getting the facts of their innocence on the court record for the sake of future propaganda and appeals in spite of the apparent hopelessness of winning a victory at that time over a picked jury and a red-eyed, lynch-exciting press. Lawyers who have gone over the records say that every one of the charges of violence could have been disproved, as in the Chicago I.W.W. case, in which the appellate court, at a later and calmer period, dismissed all the counts except those regarding expression of opinion. All this sounds plausible, but it is very easy to reason this way if one is not looking out on the world through the bars that blurred the sunlight from the tiny hole where the Sacramento defendants were herded together for a full year before trial. These men, rotting in the filth of a room so meager that there was space for only half of them to lie down at one time on the cement floor that was their only bed-rotting and dying (five died) and seeing their witnesses arrested felt that legal defense was not worth the cost. And when Godfrey Ebel, a long time I.W.W., who had been held incommunicado for a hundred days as a prosecution witness, was finally thrown into the indictment with the rest because he refused to line up against his fellow workers, then it seemed more absurd than ever to expect any justice from the federal authorities in California.

Three and a half years have passed since the blazing defiance at Sacramento, and the eloquent silence of 1919 has changed to the deadening hush of the prison corridor. There is nothing dramatic in doing time, and the labor world, fighting for its life against the open shop drive, is paying heed to other and more exciting scenes. There is danger that these brave men will be forgotten by all but their fell ow workers in the far west and a few thousand others. And even the splendid campaign now being carried on by the General Defense Committee and other organizations for the release of all war-time industrial prisoners may hardly roll back the stone that is being cemented over their memory by time.

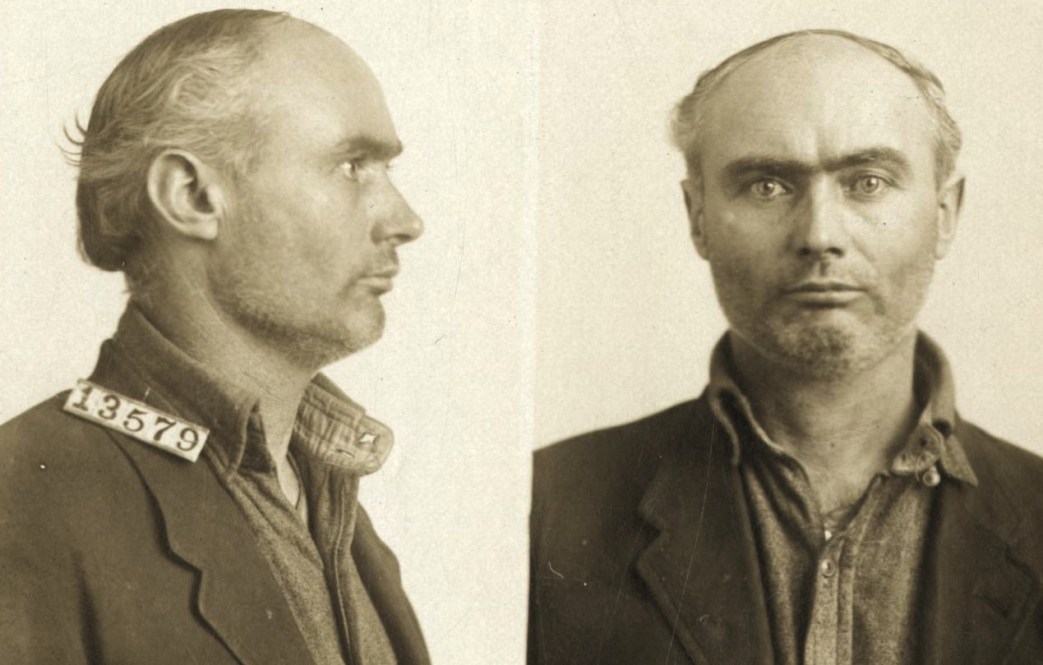

The campaign in behalf of the twenty-six Silent Defenders still in Leavenworth has greater obstacles than those that beset the work for the rest of the politicals. Among the Chicago group, for instance, are poets, speakers and organizers who are known nationally and internationally. Their names were carefully selected for the indictment because they stood out from the mass. In the five months’ court drama before Judge Landis their personalities unavoidably received still further advertising. In fact, one of the Chicago defendants now at liberty had attracted so much attention as a writer of beautiful lyrics that such champions as H.G. Wells and Hudson Maxim came to his aid. But the case of the Silent Defenders by its very nature did not lend itself to such support and publicity. Through their policy of refusing to go on the witness stand or to take any other part in the trial, the identity of each defendant was lost in the silent group. And in addition their ranks included few notables in the labor world. With few exceptions they were the everyday I.W.W. of the West, the job rebels who had come into the only union that seemed concerned with the welfare of the men who followed their line of work. They were the migratory laborers in the seasonal industries of the Pacific Coast, the “bindle stiffs,” who carry their blankets from the harvest fields to the lumber camps and the construction jobs. They are a class of men who are almost looked, on as a separate species by their more fortunate brothers. Strong and inured to hardship they are, but cut off from the ordinary social life of the race. With no one to help them but themselves, they had begun to band together into the I.W.W. In the opportune period of war hysteria the California, authorities cast a dragnet out at I.W.W. halls, employment offices and other congregating places, and gathered them up as they came, the rank and file of the union that was endangering the low wage scales in the seasonal industries.

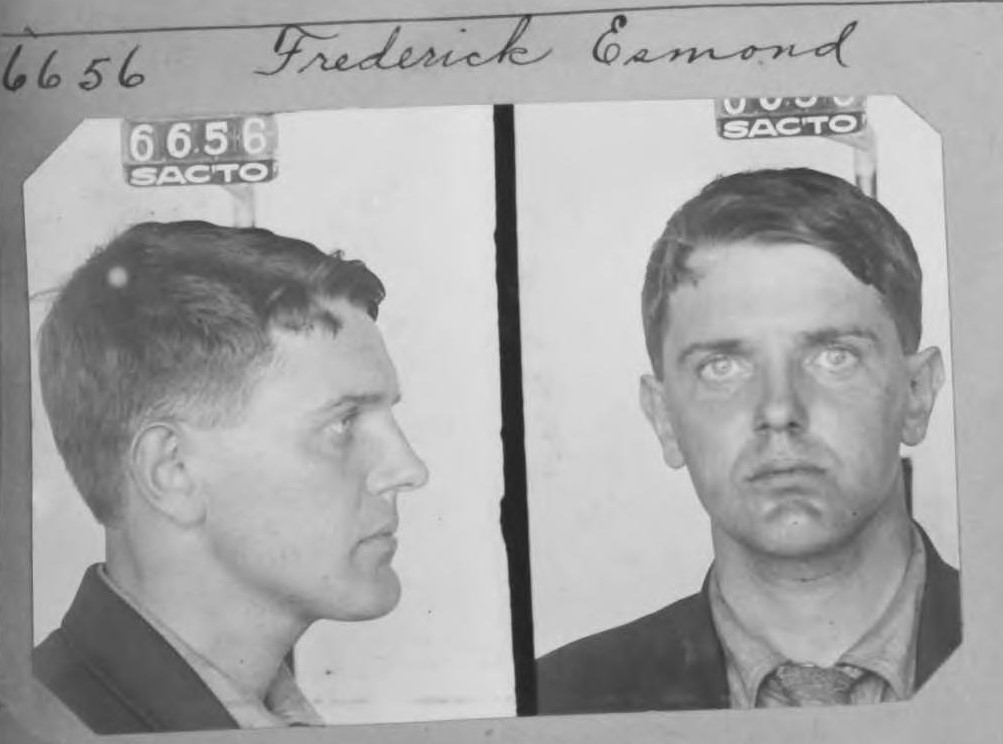

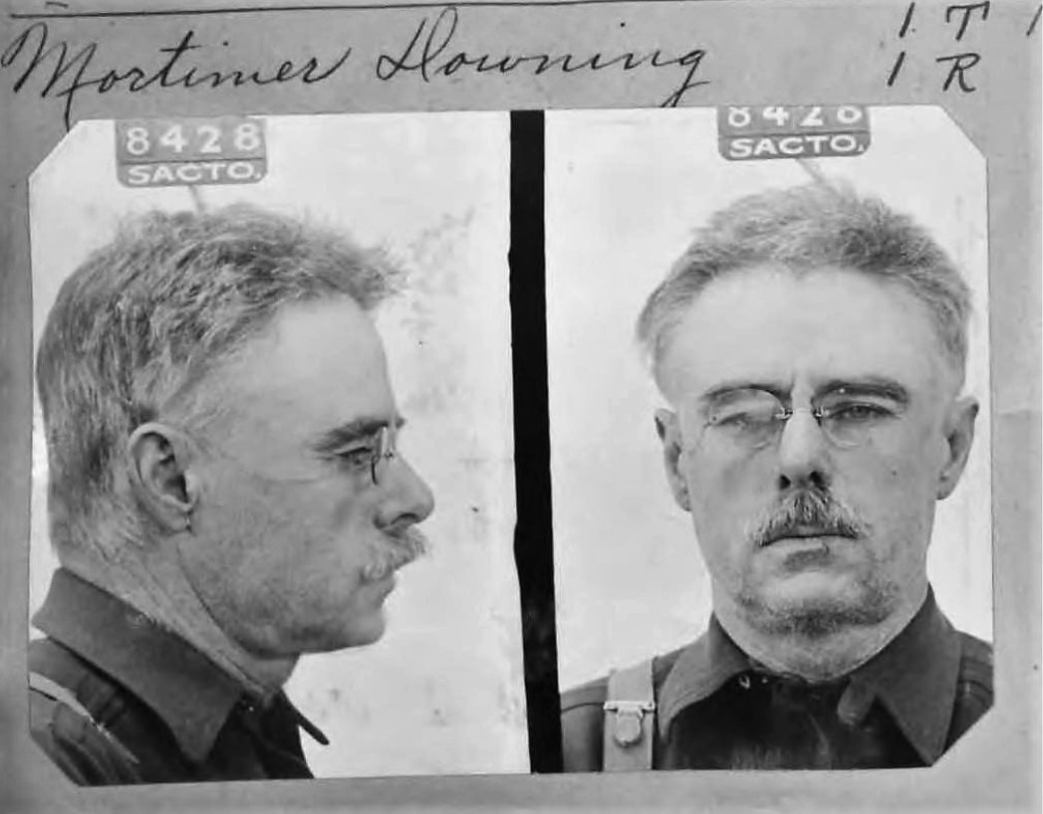

It is true that there were a few exceptions to this general classification. For instance there were Mortimer Downing and Fred Esmond, the first a Washington correspondent and special writer for many years, the latter an Oxford graduate of brilliant attainments. Mortimer Downing I saw in Leavenworth, a tall, courtly man, giving no hint of his sixty years, with a back as gracefully supple as an Indian athlete’s and eyes that looked straight into yours. He was teaching the class in advanced English, a task voluntarily added to his regular penitentiary stint. There was a vigorous poise, a strength in repose, about him, that made me want to talk to him for one minute more, but the guard was tugging at my arm, and I had to go.

But far and away the majority of the Sacramento men were a rough and ready lot of migratory workers, though with more nervous energy and determination than belong to the ordinary unorganized worker. Their native mental energy they are now showing in their prison studies, where they are coining their leisure hours into treasures for future use by following engineering specialties and foreign languages. And the hardships and discouragements of prison have failed to turn any of them, so far as a visitor can learn, from the intention to take up their union activities again so soon as they shall be released.

It seems unfair to mention any more individuals, or to leave unerased the mention that has already been made, because it is impossible to mention all, and the Sacramento group has given no encouragement to this sort of thing. But nevertheless I find it humanly impossible to follow this strict code, for as I write I cannot help listening to the conversation of several released political prisoners who, here in my room, are talking of the men they left behind in Leavenworth.

They are talking about the Sacramento group, who number more than one-third of the total list of politicals there. Just now the conversation is turning on James Quinlan, and I am getting a vivid flash of this grizzled veteran of fifty, whose spirit is still untamed after two years in the isolation cell on the charge of beating a guard. And a moment before they were telling of George O’Connell, sun-burned, squarejawed and brave-hearted, whose unfailing reply to all speculations about the opening of the gates is, “Father Time will take care of it.” And now one of the boys is wondering how Bill Hood’s little patch of flowers is getting on, and is picturing Bill’s tender care of the sprigs of green and petals of gold and rose rising out of the tiny rectangle allowed to him in the sunbaked prison yard.

It’s a long, long way to Leavenworth, and the radical or liberal resting in the cosy life of New York, with its brilliant theatrical entertainments like the “Hairy Ape” within call, and the roaring surf in easy reach for a plunge is likely to pay little heed to the sorrow and injustice of this far-away case. Distance lends forgetfulness to all but a few. The ones who do not forget, however, are the men who are bound to the California boys by no distant ties of abstract sympathy, but by the glowing bonds of comrades who have fought together in la common cause.

The Liberator was published monthly from 1918, first established by Max Eastman and his sister Crystal Eastman continuing The Masses, was shut down by the US Government during World War One. Like The Masses, The Liberator contained some of the best radical journalism of its, or any, day. It combined political coverage with the arts, culture, and a commitment to revolutionary politics. Increasingly, The Liberator oriented to the Communist movement and by late 1922 was a de facto publication of the Party. In 1924, The Liberator merged with Labor Herald and Soviet Russia Pictorial into Workers Monthly. An essential magazine of the US left.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1922/09/v5n09-w54-sep-1922-liberator-hr.pdf