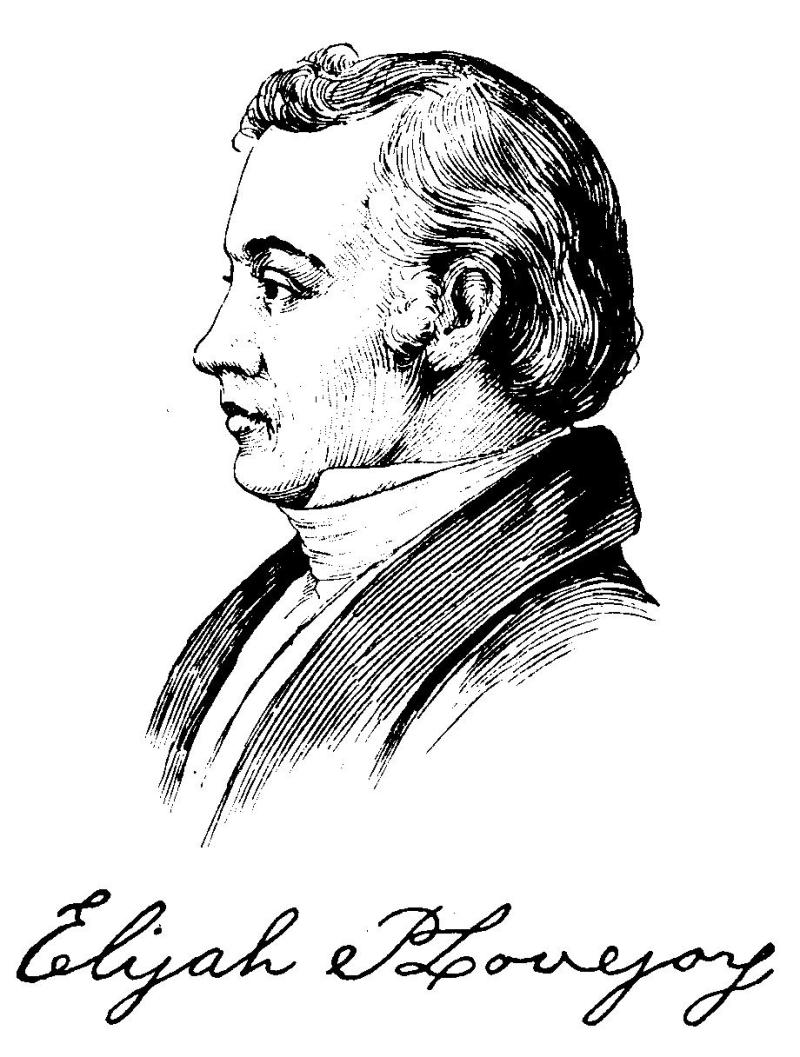

Elizabeth Lawson brings the story of a critical moment in the abolitionist movement, the 1837 murder of anti-slavery publisher Elijah Lovejoy in Alton, Illinois, to a new generation on its hundredth anniversary.

‘The Martyrdom of Elijah Lovejoy’ by Elizabeth Lawson from Labor Defender. Vol. 13 No. 4. May, 1937.

In Alton, Illinois, stands a slender white shaft erected to the memory of Elijah Lovejoy, minister, newspaper editor, and fighter for the anti-slavery cause, who one hundred years ago gave his life, as the monument proclaims, “in defense of the liberty of the press.”

Lovejoy was the first to fall in an era which has been called “the martyr age of America.” The southern slave-owners and their northern allies, the bankers and the men of commerce, met the challenge of the rising Abolition movement of the thirties with violence and terror. Civil rights were crushed under the heavy hand of the slavocracy. The national government, creature of the slave power, for years denied the right of petition; statute-books were blotted with sedition and insurrection laws; there was rifling of the mails, and burning of books and newspapers. With the connivance of city authorities, anti-slavery meetings were attacked and routed; public halls were burned and newspaper plants smashed; college students and professors were expelled for anti-slavery discussion; ministers were arrested in their pulpits for denouncing human bondage. Vigilance committees tarred, feathered, lynched Abolition speakers. The great orator of Abolition, the fugitive slave Frederick Douglass, exclaimed: “The white man’s liberty has been marked out for the same grave as the black man’s.”

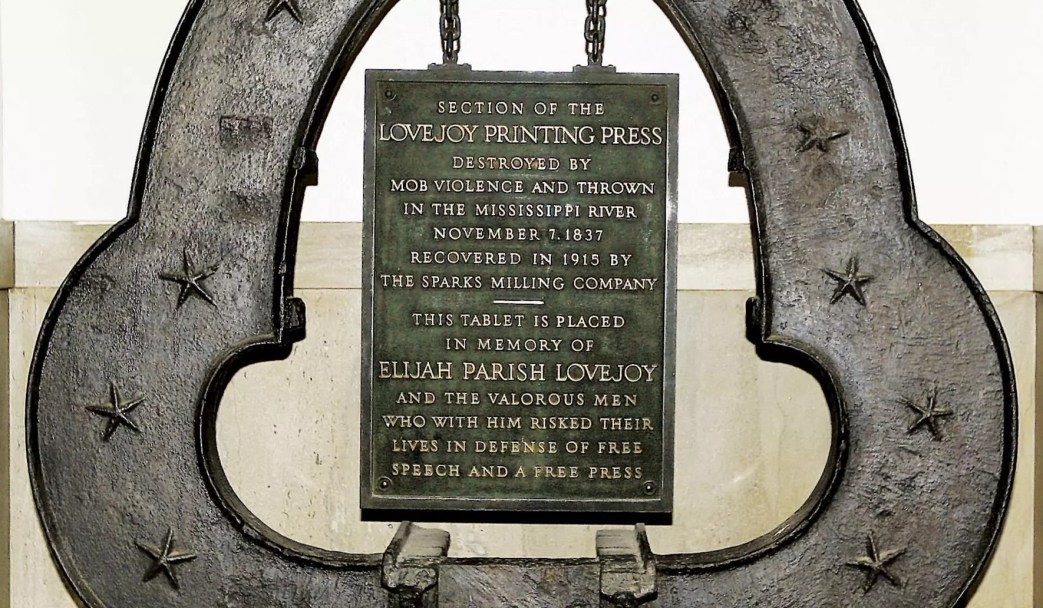

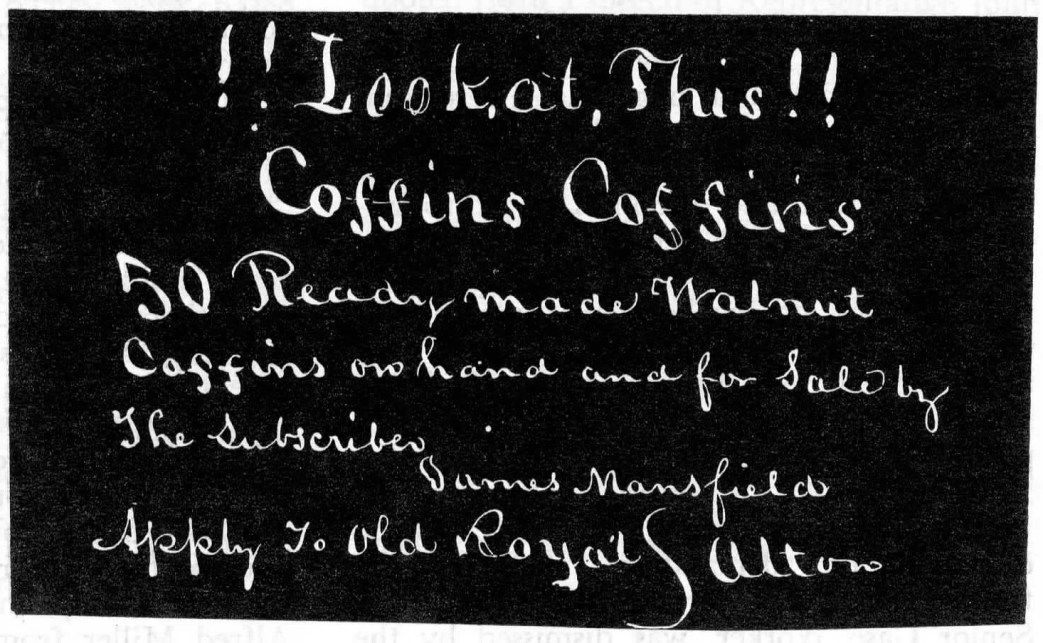

When William Lloyd Garrison, editor of the Liberator, was dragged through the streets of Boston in 1835 with a rope about his body, observers noted that his tormenters were “a mob in broadcloth.” When in 1837 Elijah Lovejoy’s anti-slavery press was sacked and thrown into the river, the mayor of Alton declared that he had never before witnessed “such a gentlemanly mob.” Upon the “mob in broadcloth,” history can lay a heavy load of responsibility for the destruction of human liberty in pre-Civil War America. These were the aristocrats of northern commerce and finance, whose pockets were filled with the proceeds of southern trade, and whose consciences were padded with southern cotton.

Under Lovejoy’s editorship, the St. Louis Observer became the first anti-slavery paper published in a slave state. Only the Observer, of all the newspapers of the South, dared to speak out in protest when in 1836 the Negro Francis McIntosh was chained to a tree and burned alive in St. Louis. There followed a series of attacks upon the Observer office, and upon the home and person of the editor, which finally forced the removal of the paper across the state line to Alton.

In Missouri, Lovejoy had been the victim of the slave-owners; in Illinois he became the victim of the slave-owners’ more hypocritical allies. The press which was sent from St. Louis was seized by a mob and broken to pieces upon its arrival at Alton. At once the citizens of Illinois collected funds for a new press. This second press, and a third as well, were destroyed. The city council refused protection; the local ministry urged that thepaper be abandoned; the district attorney took the stump at public meetings to whip up feeling against the Abolitionists.

On November 2, 1837, there met in the counting-house of a leading merchant of Alton the most respectable and influential of the city’s businessmen. They rejected a proffered resolution for freedom of the press, and another denouncing mob rule. They adopted instead this resolution: “That while there appears to be no disposition to prevent the liberty of free discussion through the medium of the press or otherwise, as a general thing, it is deemed a matter indispensable to the peace and harmony of this. Community that the labors and influence of the late editor of the ‘Observer’ be no longer identified with any newspaper establishment in this city.”

At this meeting Lovejoy threw down his challenge to the business leaders of Alton. It was not abolition alone that was here involved, he stressed; it was freedom of the press and all constitutional liberties. “I dare not flee from Alton,” he declared. “The contest has commenced here, and here it must be finished. I pledge myself to continue it, if need be, till death. If I fall, my grave shall be made in Alton.”

Within a few days the fourth press for Lovejoy’s Observer arrived, and sixty citizens enrolled in a volunteer military company to defend it. A sympathetic merchant offered his warehouse for the protection of the press.

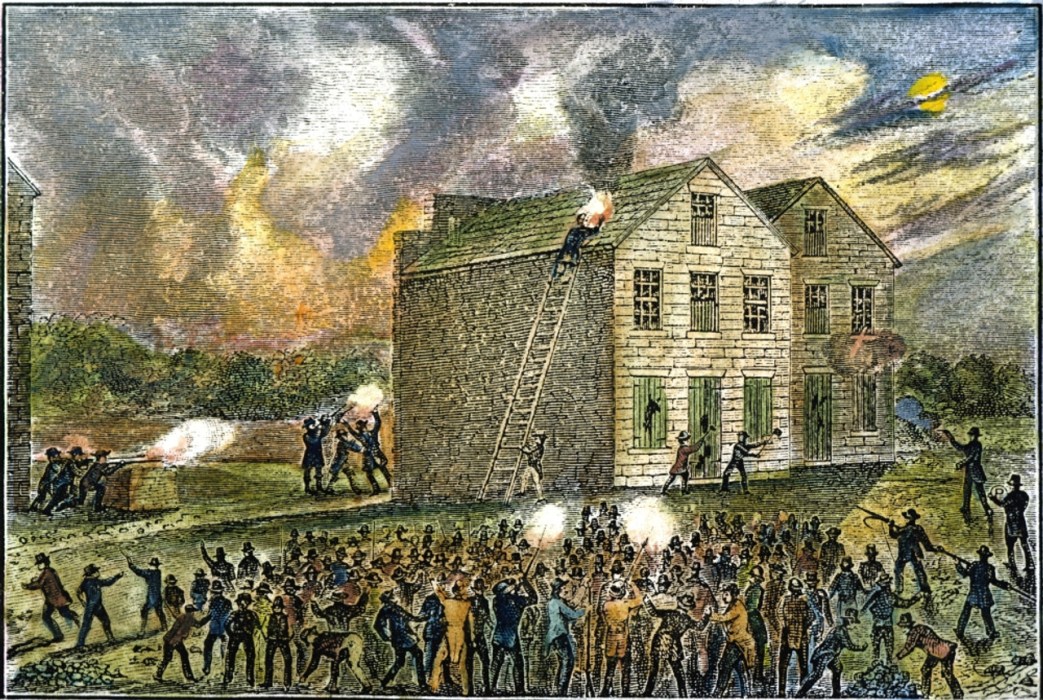

At ten o’clock on the night of November 7, a mob gathered before the warehouse. Its spokesman forced open the door, and demanded the press at the point of a revolver. The attack began with a volley of stones which broke the windows, and the firing of two shots into the building. When the fire was returned, the mob dragged forward a ladder and climbed to the roof to set the warehouse aflame. It was at this moment that Lovejoy appeared in the doorway to face the mob. An instant later five bullets pierced his body. He turned, walked a few steps towards his comrades, and fell dead. The attackers swept through the building, routed those within, and flung press and type into the Missouri River.

“The hope of conciliation with the slaveowners,” remarked a contemporary writer, “was buried in Lovejoy’s grave.” The martyrdom of Lovejoy inspired John Brown; it brought into the Abolition ranks such famed orators as Wendell Phillips; it made clear as in a lightning flash the true nature of the slavocracy and of its strangle-hold upon American life.

Labor Defender was published monthly from 1926 until 1937 by the International Labor Defense (ILD), a Workers Party of America, and later Communist Party-led, non-partisan defense organization founded by James Cannon and William Haywood while in Moscow, 1925 to support prisoners of the class war, victims of racism and imperialism, and the struggle against fascism. It included, poetry, letters from prisoners, and was heavily illustrated with photos, images, and cartoons. Labor Defender was the central organ of the Scottsboro and Sacco and Vanzetti defense campaigns. Editors included T. J. O’ Flaherty, Max Shactman, Karl Reeve, J. Louis Engdahl, William L. Patterson, Sasha Small, and Sender Garlin.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/labordefender/1937/v13-%5B11%5Dn04-may-1937-orig-LD.pdf