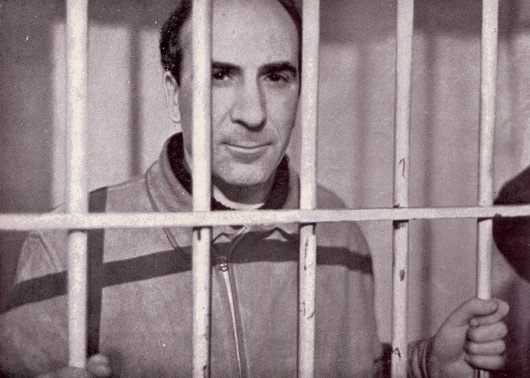

Stephen Alexander review a showing of Luis Quintanilla’s work on Madrid street life at New York’s Pierre Matisse Gallery in late 1934 as the artist was imprisoned for his role in Spain’s revolutionary crisis that year. Alexander uses the person of Quintanilla to distinguish between the ‘artist-revolutionary’ and the ‘revolutionary artist,’ making a dig at Ernest Hemingway in the process. Quintanilla would moved to New York in 1938 as Franco’s armies advanced.

‘Quintanilla’s Etchings’ by Stephen Alexander from New Masses. Vol. 13 No. 10. December 4, 1934.

HERE are some of the finest drawings any etcher has ever scratched onto metal. They are the work of a Spaniard, Luis Quintanilla,1 now in jail and facing a court-martial for participation in the revolt of the Spanish workers against the Lerroux Fascist dictatorship.

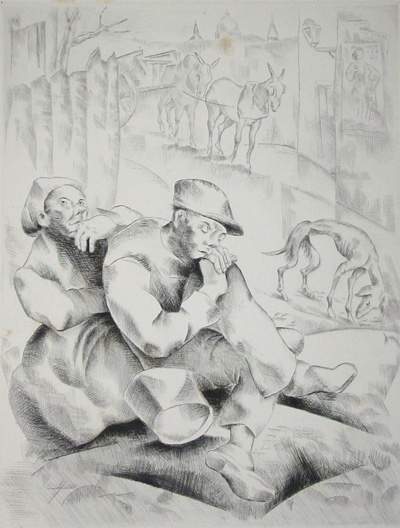

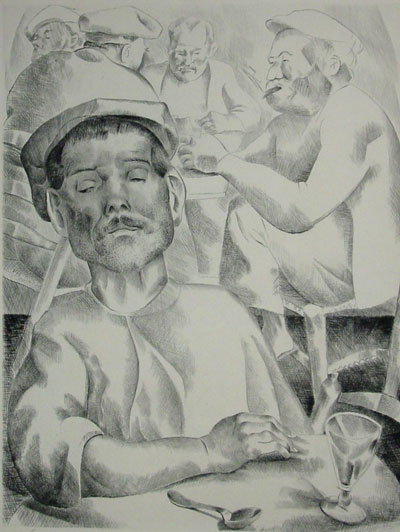

Quintanilla’s art may be described by analogy with that of a photographer with a fine fast lens who goes about portraying what he comes across.2 Here a group of street performers amusing a crowd; or a “big shot” getting his shoes shined as he exudes smug satisfaction with his world; a youth making love to a girl on a park bench; a worker’s family at home; the interior of a train in the center of which is a fat, corrupt-looking priest; a cheap brothel behind a cafe; a young woman playing solitaire; the audience in a theatre; etc., etc.

These plates raise some interesting problems for the artist who is sympathetic to revolution and trying to formulate a set of values which will give his work definite direction and integrate it with the rest of his thinking. Quintanilla’s art may be characterized as “class-conscious” art. His deeply sympathetic portrayal of the Spanish worker sitting at a table or at home with his family, his ridicule of the Church or his satirical depiction of the “big-business man,” leave no doubt as to the class position of this artist. His sympathies are unmistakably with the working-class. But Quintanilla is not a revolutionary artist, as some have claimed for him. He is an artist-revolutionary. There is a difference, a very important difference. The revolutionary artist makes his art a class weapon, whereas Quintanilla is a revolutionary who happens to be an artist, whose art does not reflect his feelings and reactions to the world in which he is living, whose art has little or no relation to his social and political ideas.

With the exception of a few mildly satirical comments of a class nature, (perhaps three or four) these plates are essentially decorative. They are hardly up to what we would like to see from an experienced revolutionary. Let us consider in this connection the work of Daumier, or of Grosz. These artists also looked at the world about them…and their drawings were so searing in their acidity as to be considered dangerous to the ruling class. They were jailed for their art. Quintanilla is in jail for his political activities. He is a revolutionary in his politics but not in his art. I am not attempting here to advocate one form of activity as preferable to the other. Both are necessary. The question of how an artist may best serve the revolutionary movement with his art, or by political activity, or various combinations of the two, is determined in practice, by the artist and by the comrades who evaluate his usefulness in the light of the needs of the revolutionary movement at any given time. But for clarity of understanding, in an evaluation of art work, it is necessary to make the above distinctions.

We believe that an art which raises the revolutionary consciousness of the masses, which gives fine plastic and graphic expression to the class struggle-in short, “good revolutionary art”-is the most useful kind of art for our purposes, hence for us the “highest” form of art. The statement of this truth may seem so obvious to the experienced revolutionary artist as to appear redundant, but a great many artists just approaching the revolutionary movement are still very confused on such basic issues. Some of them will, I am sure, feel that such an evaluation of Quintanilla’s work is too severe or narrow a judgment (and some of our bourgeois aesthetes would probably consider it the wild ravings of “propagandists”) but that is largely due to the carry-over of bourgeois prejudices and conceptions about the “nature of art,” which for them means the reduction of all art to purely technical display and sterility of content.

By the way, don’t let that little piece in the catalogue by Senor Hemingway prejudice you against Quintanilla. The Big Toreador and Bull-Thrower cannot write fifty consecutive words without sneering at or viciously attacking artists and writers who express their revolutionary feelings and beliefs in their art and literature. You shouldn’t hold it against Quintanilla. He is a fine artist.

NOTES.

1. Pierre Matisse Gallery, Fuller Bldg., 57th and Madison.

2. Technically his art is quite removed from the technique of photography. He uses creative distortion frankly and masterfully.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s to early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway, Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and more journalistic in its tone.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1934/v13n10-dec-04-1934-NM.pdf