‘Coal Civilization in Eastern Kentucky’ by Alonzo Walters from the Industrial Pioneer. Vol. 11 No. 11. March, 1925.

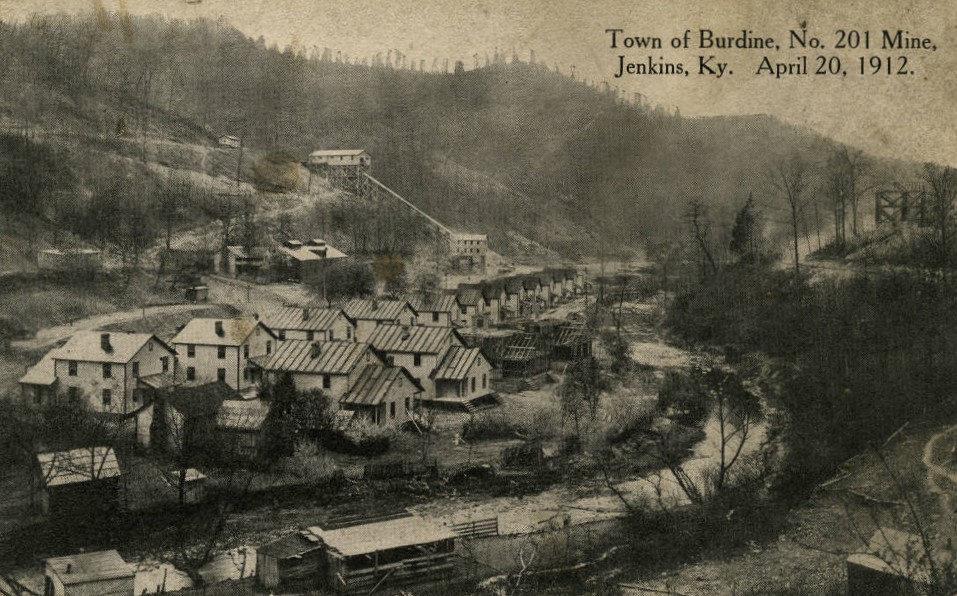

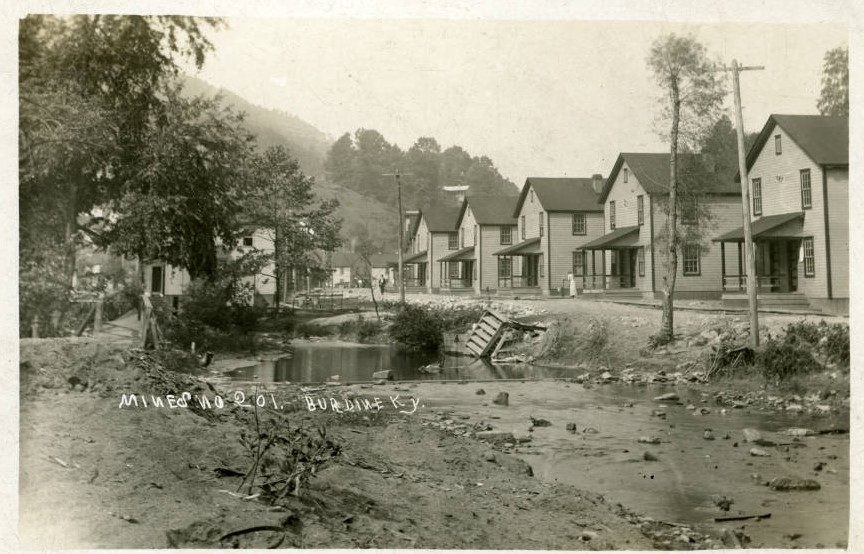

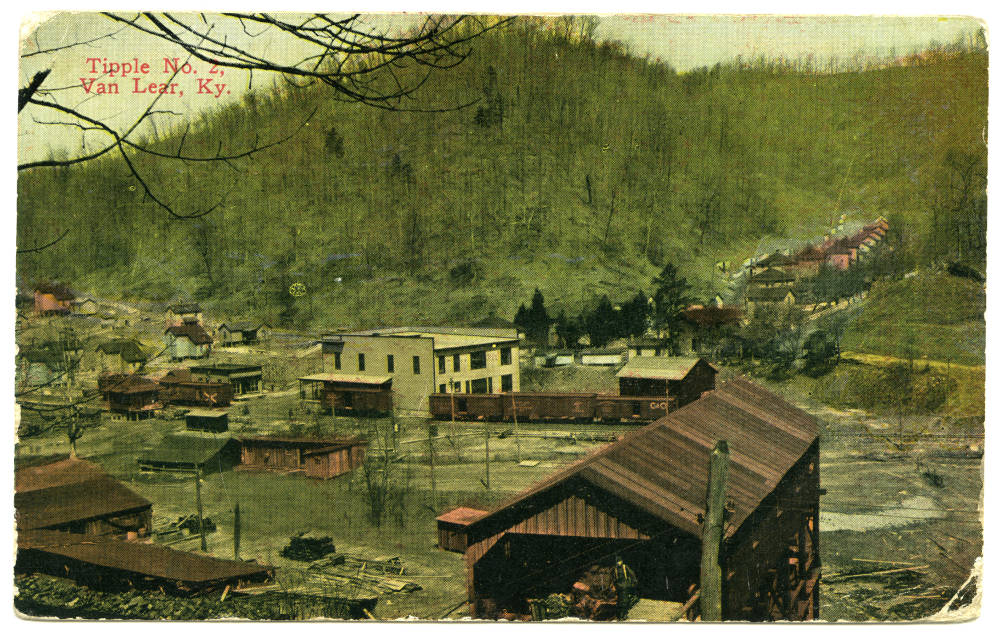

DOWN in the heart of the Cumberland mountains, on the banks of the Kentucky river, less than 70 miles from the Virginia line, lies a little mining town of about eight thousand inhabitants. This town is called Hazard. It is in Kentucky and rises in the center of what is known as the Hazard Coal Field. Other mining towns and hundreds of mining “camps” dot the valley of the Kentucky along a distance of 45 miles to the north and 58 miles to the south of Hazard. Thousands of wage slaves toil in the mines that have been opened up in that region since the first railroad line, a branch of the L. & N., was run into that region in 1912, and live with their families in the filthy camps.

Fifteen years ago Hazard had a population of less than one thousand. Fifteen years ago none of the hundreds of mining camps now to be found in the district were there. Fifteen years ago the railroad extended into that region no farther than Jackson, Kentucky, 45 miles north of Hazard. As late as then wage slavery did not exist there. The people- all natives- lived their lives, happy and content in their own quiet, simple way. Their only industries, or occupations, worth speaking of were tilling their small mountain farms for a living which, simple and rude though it would probably seem to most of us, quite satisfied all their tastes and demands, — this, and making the best moonshine liquor that ever kissed the lips of men. For pastime they hunted the small game that abounded in the hillside woodlands, or fished from the Kentucky river or some of the numerous creeks that are its tributaries. The young folks now and then went to “bean shellings,” “apple cuttings,” or old fashioned country “parties,” and the old folks on Sundays went to “preachings.” Occasionally, when some of them wanted a little excitement, a feud was started in which some two or more leading families of a community or locality proceeded to kill each other off. They knew nothing of the vices, crimes, filth, labor hells and other blessings of modern civilization, and modern civilization had not yet heard of them, or, at least, was not yet interested in them.

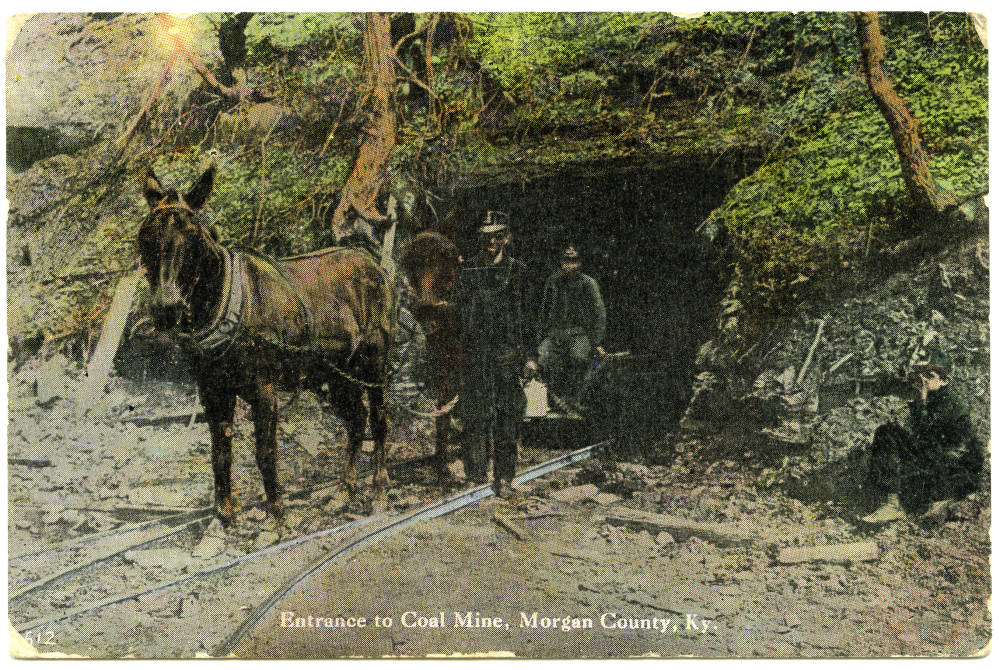

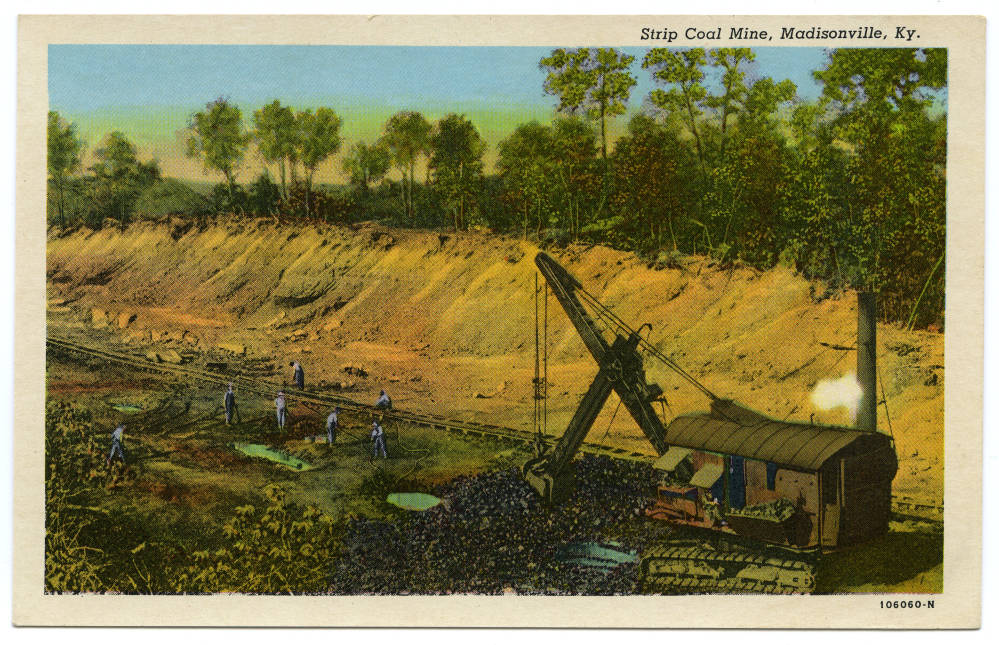

Then suddenly it was discovered that these mountains contained three very rich layers of coal, extending the entire length of that portion of the Kentucky valley, which traverses the mountain region: Then it was that modern civilization, or modern capitalism, which is the same thing, began to develop a very lively interest in this benighted section and its primitive people, and decided to bring to it and them all the above mentioned blessings and many others.

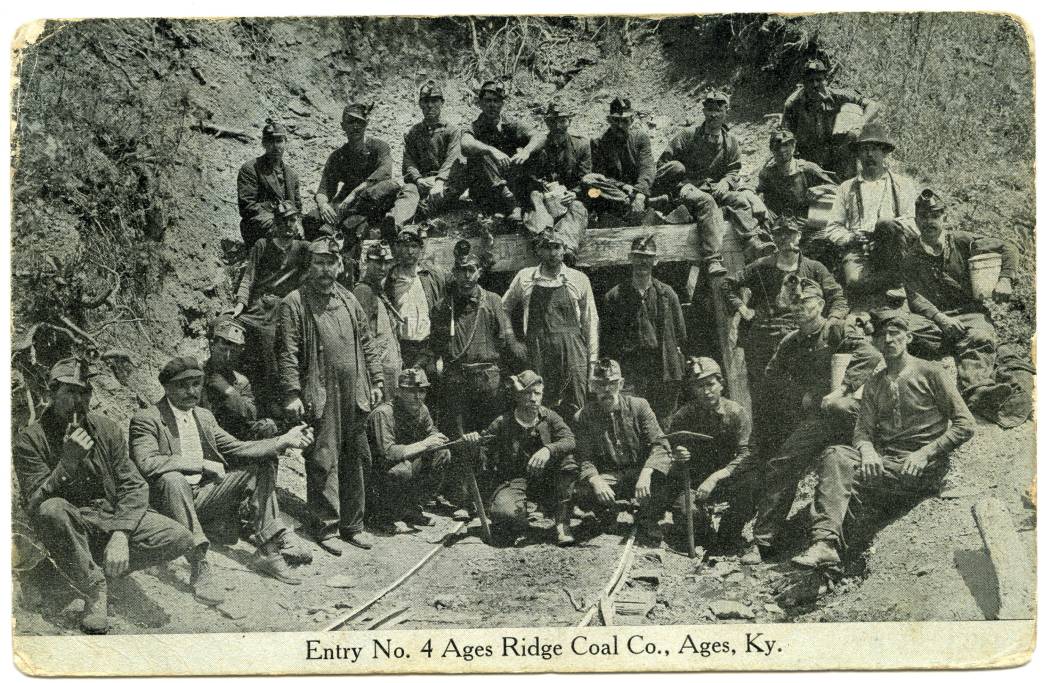

Now let us take a brief glimpse at this region, the Hazard Coal Field, as it has since come to be known. It would be hard to find a more deplorable, a more abominable form of slavery anywhere in the world, or in any age of history than the system of wage slavery that now exists there. Because of the fact that this region is just now in the infancy of its industrial development, and coal mining its only important industry in which wage slaves can find employment, thousands of workers are absolutely at the mercy of the coal barons. They are dependent upon them for jobs; they live in their houses, and they trade at their stores. Hence, it follows that when one of them has incurred the ill-will of his master for any reason he is thrown out with his family upon the road; his credit is cut off, and he is blacklisted throughout the entire district, so that it is impossible for him to get a job without leaving the whole coal field.

Sample of “Prosperity”

The coal miners in that field have had three wage cuts within the past year. At present, local loaders are being paid 40 to 50 cents per “ton” of 3,000 pounds or more for digging coal in mines where the average thickness of the coal seam is about 40 inches. In addition to mining the coal, they must re¬ move a streak of “jack rock” which varies from eight to eighteen inches in thickness, and all overhead slate, for which labor in most mines of the Hazard field nothing is paid. Out of this meager wage they must buy from the coal companies all their tools and working material, such as carbide, lamps, blasting powder, fuse, shooting paper, etc.

One coal miner, at Blackey, Kentucky, told me a few days, ago that for eleven days’ work for the Bertha Coal Company his total earnings were only $22. Day wages range from $2 to $4.50 a day, the latter figure being the wage to the most highly skilled and extemely dangerous and responsible jobs.

While on a two-week visit to the Hazard Coal Field, in addition to gathering a lot of other data, I compiled a number of tables showing the prices which miners must pay for the barest necessaries of life in the company stores where they are forced to trade. The following, which is a table of prices charged by the Hazard-Blue Grass Coal Corporation, will serve as a typical illustration:

Light overalls, per suit. $5.00

Light work shirts, each. 1.00

Canvas gloves, per pair. 50 to .75

Flour (24-pound sack). 1.50

Salt bacon, per pound. 30

Breakfast bacon, per pound. 75

Ham, per pound. 50

Beans, per pound. 10

Butter, per pound. 80

Independent stores located near some of the mining camps sell the same articles from 20 to 40 per cent cheaper, but most of the miners are always in debt to the company stores.

Now just a word about health and sanitation in the mining camps of the Hazard Coal Field. The outhouses, or toilets, little wooden shacks built usually within 30 or 40 feet of the dwelling houses of the miners, are allowed to go uncleaned for months, or when cleaned the refuse is buried in the ground nearby. Water in the wells and springs which supply families of coal miners is, of course, full of deadly disease germs.

Fixing it for the Doctors

In some cases several families have to use the same toilet. In one camp which I visited while on my recent trip, three families were using the same toilet and those in two of the houses using it were Obliged to apply to the family acting as custodian of the key with which the toilet was locked. Epidemics of such diseases as typhoid are common in these mining camps.

The miners are completely at the mercy of the company doctors, who receive their salaries from monthly deductions from miners’ pay envelopes. No matter how incompetent and insolent these doctors are the miners have to put up with them. One coal miner who called an independent doctor was severely reprimanded by the mine superintendent, and threatened with discharge if such a thing occurred again. The company doctor, being called again to see the little child, was angry and refused to go. The baby died the following morning. The father was in such desperate financial straits, due to the shamefully low wages he had been receiving, that he was unable to pay for burial expenses and had to appeal to the charity of his neighbors. A wooden coffin was made by a friend, and burial clothes were bought with donations made by neighbors.

Although these company doctors receive handsome regular salaries from the miners, they never lose an opportunity to charge extra for treating a case when they can get away with it. Their charge for an obstetric case is $25. The little son of an Italian coal miner was bitten by a mad dog last summer. His father was compelled to pay for the medicine used in the hydrophobia treatment. This cost him $23, and the doctor charged him $2 a shot for administering the treatment. Foreigners, who are most ignorant of the customs of the locality, and negroes, are quite naturally the easiest and most common victims of these scoundrels.

Official Corruption of District

The post office in a mining camp is located in one end of the company store, and the postmaster in every case is a store or office clerk of the coal company. This enables the bosses to keep a tab on the kind of mail their slaves are receiving and sending out from time to time. In this manner knowledge is gained by the coal companies whether any of it comes from or goes to undesirable parties.

The coal companies of the Hazard Coal Field have one of the most thorough and efficient systems of thuggery that was ever planned and devised. One or more deputy sheriffs are stationed in every camp, and these deputies are in every case cutthroats and murderers of the vilest and most abominable type. Judging from the kind of material always appointed deputy sheriffs in this region, a man is not eligible for such a position until he has killed some people. The tamest and gentlest deputy I know of there is a man by the name of Collins, at Blackey. This fellow has never yet killed any white man.

The high sheriff of Perry county, of which Hazard is the county seat, is the son-in-law of J.C. Campbell, principal owner of the Campbell Coal Company. Campbell served one term as judge of Perry county, and is now the representative of that district in the state legislature of Kentucky.

The present circuit judge of that judicial district, a man by the name of Rufus Roberts, complained to all his friends at the time of his election in November, 1921, that he was head over heels in debt. Within the first two months of the railway shopmen’s strike he built a magnificent residence in the little town of Hazard costing more than $30,000.

The last sheriff of Perry county boasted openly that he cleaned up $50,000 in his four-year term, on a salary of about $2,500 per annum. Some saving!

Third Party Out of Luck Here

The elections in mining camps are always held in a company building, with an election board made up of coal company officials and office clerks. Although Kentucky has a secret ballot law the coal miner who votes must vote his ballot openly and in the presence of this picked election board.

Such is the present condition of the wage slaves who inhabit the winding, mountain valley of the north and middle forks of the Kentucky river; a region that only a few short years ago was one of the most beautiful, picturesque, poetic and romantic areas of the world; a region inhabited by a people who knew nothing of the indescribably and unspeakably sickening and deplorable conditions that have, within the short space of less than a decade and a half, been brought to that territory by the blighting hand of twentieth century “civilizing capitalism.” As I think of the trend of events of the last few years in that region the following couplet from Goldsmith’s “Deserted Village” comes forcibly to my mind:

“Ill fares the land, to hast’ning ills a prey.

Where wealth accumulates and men decay!”

The Industrial Pioneer was published monthly by Industrial Workers of the World’s General Executive Board in Chicago from 1921 to 1926 taking over from One Big Union Monthly when its editor, John Sandgren, was replaced for his anti-Communism, alienating the non-Communist majority of IWW. The Industrial Pioneer declined after the 1924 split in the IWW, in part over centralization and adherence to the Red International of Labour Unions (RILU) and ceased in 1926.

PDF of full issue (large composite file): https://archive.org/download/case_hd_8055_i4_r67_box_007/case_hd_8055_i4_r67_box_007.pdf