Ben Gitlow, recently released from prison, with a thorough look at the 1926 Communist-led strike of silk workers in Passaic, New Jersey, a city of many past class battles. Arguably the Party’s most important leadership of a mass struggle in the 1920s, Passaic also saw Ben’s mother and comrade, Kate Gitlow, assume a central role as President of the United Council of Workingclass Housewives.

‘The Passaic Textile Workers Strike’ by Ben Gitlow from Workers Monthly. Vol. 5 No. 8. June, 1926.

THE country which is now aroused over the industrial war going on in Passaic, took very little cognizance of its beginning. The strike began on January 25, in the Botany Mill, the largest mill in Passaic. It was provoked by the discharge of workers for belonging to the United Front Committee. Its real cause was the last wage cut that this mill had initiated a few months before.

The Sources of the Strike.

When the 40 delegates from the various departments of the mill presented their demands to Col. Charles F. Johnson, the vice-president of the mill, for the abolition of the 10% wage cut, time and half for overtime, the reinstatement of those discharged and for no further discriminations against union men, they found present a squad of police headed by the chief of police of Passaic by the name of Zober. Zober tried to eject the workers from the mill after Col. Johnson had flatly refused the demands thus indicating at the very start of the strike that the government of the city of Passaic was hostile to the workers and would use its power in the interests of the mill owners.

The mill owners tried to avoid the issue of the workers’ demands by raising a fake issue of Communism. In the afternoon of the first day of the strike the Botany Mill issued a statement justifying the wage cuts which included the following:

“Shortly after this Passaic was visited by a small group of outside agitators who began to have meetings at which literature was given out, principally of a nature extolling the virtue of the Soviets and calling upon the workers to organize along similar lines. They described themselves as the United Front Committee and among their principal speakers was one by the name of Gitlow associated with the Communistic Party in New York. Viewing the walkout not as a result of justified grievances but as a result of professional agitators who have no interest in our working people the management is determined to protect to the utmost those who desire to work.”

The mill owners and all the opponents of the strike maintain this attitude to date in spite of the fact that the strike has upon the basis of its economic demands won wide support from all sections of the labor movement.

The Strike Spreads.

The strike which started in the Botany Mills, soon spread to the other mills. There are now over 16,000 workers out on strike from the following mills: The Botany Consolidated Mills of Passaic and Garfield, Passaic Worsted Spinning, Gera Mills, New Jersey Spinning, Forstmann and Huffmann Mills, Dundee Textile, a silk mill, United Piece Dye Works of Lodi and the National Silk Dyeing Plant of East Paterson, the last two being dyeing mills. The strike has spread from woolen mills to one silk mill and two silk dyeing plants.

The leader of the strike is Albert Weisbord. The strike has been conducted in a well-organized and masterful manner. The strikers have organized their own force to keep order. This force, which is designated by orange bands around the arm, directs the picket lines and sees to it that the strikers deport themselves in an orderly manner. The Passaic strikers in this matter are giving a demonstration of the ability of workers to handle well their own affairs in a critical situation.

The Nature of the Strike.

Passaic is maintained by the Botany and other large textile mills as an open shop paradise. The Botany is the largest concern in Passaic. It has been making a profit of approximately 93%. In the last 3 years it has been making a net profit of almost $3,000,000. The other mills have been making profits on their investments relatively as high. Nevertheless, these mills have been paying starvation wages. The majority of workers in Passaic earn from $10 to $22 per week. The basis of the strike is the rebellion of the workers against low wages and inhuman conditions. The fact, however, that they did not go out on strike immediately following the wage cut, but insisted upon being organized first and did strike when members of the United Front Committee were discharged by the Botany Mills, indicates that this strike is also a strike for organization. The organization or building of the union phase of the strike is of vital importance to hundreds of thousands of unorganized workers in the textile industry.

Since many of the workers struck against mills that had not cut wages, tho the wages in these mills were not higher than those paid in the mills that did, the United Front Committee had to reformulate the demands so that they would be general and form the basis for rallying all the workers to continue to struggle against the bosses. On February 4, the following new demands were made public:

- Abolition of the wage cut and a ten per cent increase in wages over the old scale

- Time and a half for overtime.

- The money lost by the wage cuts to be returned in the form of back pay.

- A forty-four hour week.

- Decent sanitary working conditions.

- No discrimination against union members.

- Recognition of the union.

The Development of the Strike.

The parade held during the second week of the strike was a splendid mass demonstration of the solidarity and determination of the strikers to carry on the struggle until victory was won. This, together with the effectiveness of mass picketing, the successful spreading of the strike and the order maintained by the strikers, enraged the mill owners. Realizing that the strike would not disintegrate, the mill owners decided upon an open smashing policy. The incidents that followed have made Passaic famous as a landmark of the class struggle in America. The police instituted a reign of terror and brutality. Men, women and children were brutally clubbed. Picket lines were dispersed. Mounted cossacks rode into the crowds. Tear gas bombs were thrown at the strikers. Hundreds of arrests were made. Fines and jailings took place. The newspapers took notice. They printed stories and illustrated them with pictures of the atrocities. The newspaper men were then attacked by the police. Cameramen were clubbed and their cameras destroyed. Newspaper men and photographers appeared on the scene in armored cars and flew over the strike zone in aeroplanes. The strikers held firm. They defied the police brutality. They appeared on the picket lines singing, determined to hold firm. Those arrested immediately had their places filled by others. They met the clubbings with steel helmets. They met the gas attacks with gas masks. What a vivid picture of the warlike character of the industrial war in America!

The labor movement became aroused. Even the liberals rushed to the defense of the strikers. From all parts of the country the battlers in Passaic received support. The outrageous goings on in Passaic became a matter of national concern. A committee of strikers went to Washington demanding an investigation. The president refused to see the committee. The agents of the mill owners raised a howl against the demand for an investigation. The opponents of the protective tariff used the Passaic strike as an issue against the tariff. In a word, the Passaic strike became an affair of national politics. Secretary of Labor Davis rushed to the assistance of the mill owners with a proposal for settlement that meant the breaking of the strike. The strikers rejected Davis’ proposal. The governor was attacked for his inactivity and for his statement that he was without power to interfere in the situation. The mill owners had not only the strikers now to contend with, but a formidable growing outside opposition made up of all kinds of heterogeneous elements.

The mill owners retreated. The police abandoned their brutal smashing tactics. The mill owners concentrated their efforts on Washington. They raised the scare of Communism, of Bolshevist leadership of the strike. Senator Edwards, their henchman in Washington, led this campaign for them. The mill owners, however, did not succeed. They won very little support. .They brought the National Security League into the strike to conduct a campaign against Communism. They got the American Legion to actively interfere. They used the hostility of the A. F, of L. to the United Front Committee and to Weisbord to offset the protests and condemnation and demand for settlement that came in increasing volume from all quarters. When this policy proved ineffectual, they tried to vindicate its use by a series of sudden desperate raids. They raided the union headquarters and confiscated all records. They raided the relief office as well. They arrested organizer Weisbord, held him incommunicado and later placed him under $30,000 bail. This was one of their trump cards. With the arrest of Weisbord they expected to demoralize the strike.

All these desperate moves on the part of the mill owners failed to break the strike. The workers held firm. The mill owners then realized that the strike did depend upon a single leader. The storm of protest arose from all over the country. The mill owners became desperate. They renewed the clubbings and brutal violence against the strikers. The riot act was read in Garfield. Sheriff Nimo established virtual martial law. Halls were closed.’ Robert W. Dunn, Jack Rubenstein, Clarence Miller, Norman Thomas and others were arrested in quick succession and placed under $10,000 bail. Every right was taken away from the strikers in Passaic. Regardless of this terror, the workers kept up their splendid solidarity. The denial of freedom of speech and assembly was met with open air meetings in Wallington, a small town near by.

The mill owners then resorted to the injunction. The Forstmann-Hoffmann Co. obtained a most sweeping injunction against the strike. This injunction has now been materially modified. The workers are as determined today as they were at the beginning. The bosses have been defeated in all their maneuvers. They are again resorting to their original tactic of trying to raise the issue of Communism in order to avoid the real economic issues involved. At the time of writing the mill owners are issuing a newspaper named the American Review. It is a red baiting sheet. Its purpose is to try to create the impression that the Passaic strike is a move for a civil war started by Moscow. If the workers continue to keep up their spirit and enthusiasm then the mill owners will be forced to end their stubborn resistance and settle.

IT is very difficult at this time to convey the full significance of the Passaic strike. The strike is not yet over. Nevertheless, there are many important conclusions that can already be drawn. These conclusions help us to formulate the correct tactics that must be used in many of the important tasks before the party. They also bear out the correctness of the position of the Communists on many important problems, political and economic, confronting the American labor movement. These can now be touched on but briefly.

The Strikers.

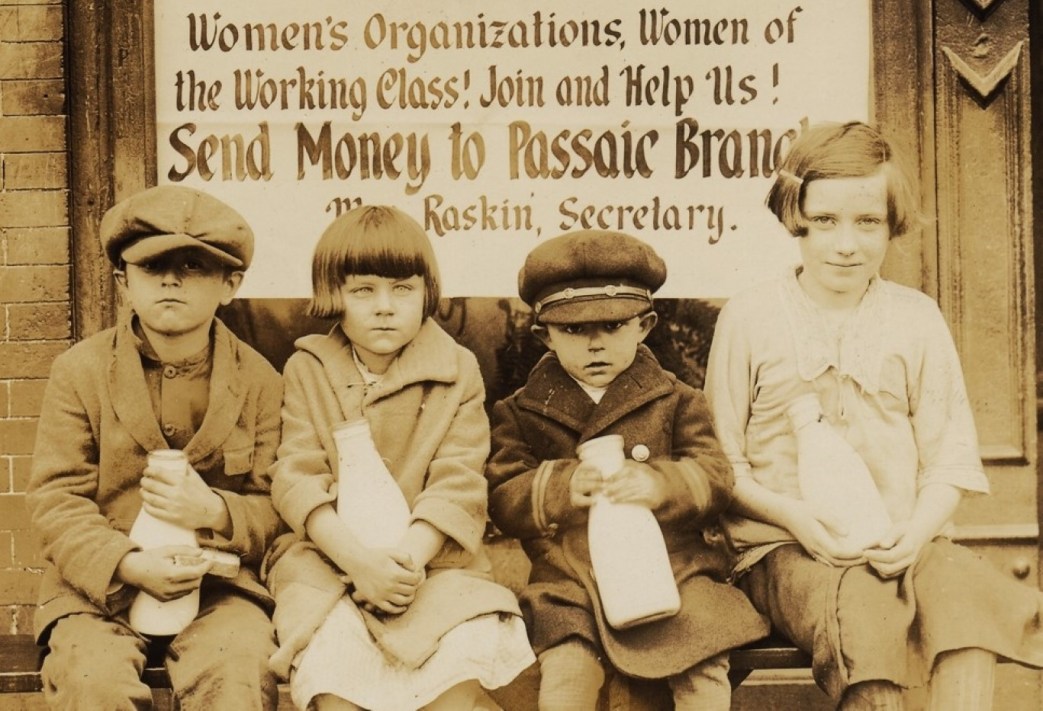

The strikers are composed mostly of foreign-born workers. The biggest percentage are Poles. Next come Italians and then Hungarians. The foreign elements, however, are welded together by their children who are American born and have followed them into the mills. This phenomenon is the aftermath of the world war following the restriction of immigration. The result is that the subjective factor for organization is now much better than ever before in the textile industry. The continual changing of the complexion of the workers from one nationality to another so common before in the textile industry is now at an end. The foreign-born workers are now much more fixed to the industry and have, so to speak, become greatly Americanized. They understand English and have acclimated themselves to many of the American customs. Their children cement the textile population into a homogeneous mass. In Passaic these young workers are the backbone of the strike and its most militant element. It means that strata of young American born workers are coming to the forefront of the struggles of the textile workers in America. This element is the new blood in the textile industry that makes militant struggle possible. It is the element that must be developed to build effective organization. The Passaic strike demonstrates that clearly.

The Textile Industry.

In the number of workers employed the textile industry is the largest in the United States. It employs approximately 1,000,000 workers. It is spread all over the country but is concentrated mainly in the southern, middle and north Atlantic states. The wages paid in this industry are among the lowest in any industry in the U.S. Woman and child labor is extensively employed. The hours fluctuate from 48 to 60 hours a week. Efficiency methods are continually applied with the result that speeding up is increased, continually eliminating*more workers. The unemployment situation is chronic, and greatly aggravated. Extreme exploitation of the workers is resorted to. A spy system is maintained. Company unions, completely dominated by the bosses and under the leadership of company Stool pigeons, are more and more being set up in the mills. In spite of the many militant and impressive struggles conducted by the textile workers in the past, the bulk of the industry is unorganized. The Passaic strike is a move for the organization of the textile workers into one union. The United Front Committee leading the strike is making every effort to unite into one union. the organized and unorganized textile workers. The United Front Committee does not oppose the existing unions in the field. It organizes the unorganized on the basis of mil! councils. At its delegate bodies it accepts delegates from whatever union happens to be functioning in a particular mill. It also allows the workers to affiliate with any union they see fit. Its main object is the amalgamation of all the existing unions into one textile union. The Passaic strike shows that the great stimulus for unity in the American labor movement and for militancy will come when the movement for organizing the unorganized develops and grows. It also indicates that the strike is an important and necessary step in organizing the unorganized.

The Strike and the Trade Unions in the Textile Industry.

The strike aroused the textile workers organized and unorganized and forced the American Federation of Labor and the unions in the textile field to take a position in reference to the strike. At the same time the mill owners also forced the issue between the American Federation and the United Front Committee when they maintained that they would deal with a bonafide union affiliated with the American Federation of Labor and not with a “Communist organization” like the United Front Committee unrecognized as it was by the American Federation of Labor.

At the beginning the attitude of the American Federation of Labor towards the strike was one of hostility. Then it veiled its hostility in a hands-off policy. The rank and file of the American Federation of Labor, however, supported the strike. Local unions from all over the country rallied to the support of the strike. Many of the labor journals adopted a friendly attitude to the strike and urged its support.

In the textile industry itself organized labor is found in three main divisions. One is the United Textile Workers, the official A.F. of L. union. The other is the Associated Silk Workers, an independent union of silk workers with headquarters in Paterson. Then there is the Federated Textile Unions, a federation of a number of independent unions.

The Federated Textile Unions from the start had adopted a very friendly attitude to the strike and to the United Front Committee. This organization agreed to call a conference of all the existing unions in the textile industry. It further favored, if the United Textile Workers participated and did not object, that the unions participating in the conference agree to the amalgamation of their forces within the United Textile Workers of America. The United Front Committee went further in its effort to achieve unity. It addressed a letter to President Green, calling attention to the need of unity and the necessity of organizing the industry and it pledged its full support to any move that the American Federation of Labor would make to achieve such unity within the American Federation of Labor. In his reply President Green ignored the request for unity, stated that the American Federation did not recognize the United Front Committee, expressed his sympathy with all workers fighting against wage cuts and for better conditions and ended with the following: The American Federation of Labor will cooperate in every practical way with the officers and members of the United Textile Workers of America in all efforts made by that organization, first to organize the men and women employed in the textile industry and, second to secure for them decent wages and more human conditions of employment.

The record of the U.T W. is black indeed. It is despised by the textile workers for the treachery and betrayal of the workers’ interest on the part of its officials. Its journal, the Textile Worker, included the ads of the Botany and other mills in Passaic that are involved in the strike: The reactionary and treacherous character of this organization can only be changed by bringing so much pressure from below by organizing the unorganized that unity of the existing textile unions will be forced. This will bring new elements into the U.T.W. and will make possible a change in its present character.

The Associated has maintained a centrist position in the textile situation. It hesitates and is afraid to make a step. It hesitated on the organization of the dyeing industry and left the field to the United Front Committee. It hesitated on joining hands with the United Front Committee on common action for improved conditions. It has, however, finally seen the necessity of electing delegates ot the Amalgamation Conference called by the Federated Textile Unions in New York for June 5th and 6th. This means that outside of the U.T.W. all the unions will participate at the conference. It may be possible that many local unions of the U.T.W. will also be present. The Passaic strike has started one of the most important moves for the organization of the textile industry by the drawing of the organized workers into one union. The U.T.W. will have a difficult time standing in the way of unity and the organization of the industry.

The Conference, if successful, will form a big block of organized workers whose numbers will increase as the drive for organization develops and the pressure upon the A.F. of L. will become great and will possibly force favorable action in the future on the question of admission.

Passaic shows how to move for unity and how to deal with the A.F. of L. The A.F. of L. has been forced to come out publicly in sympathy with the strike. Passaic proves that is only to mass pressure that A.F. of L. yields.

The Strike and the Role of the Government.

The strike has vindicated the position of the Communists that the government is hostile to the workers and is used by the capitalists as a weapon against the workers in their fight for improved conditions. The outstanding proofs of this are the actions of the Passaic authorities— over 200 strikers arrested, the hostility of the mayor and the judges, the brutality of the police, the antagonism of the governor of the state of New Jersey, the use of sheriffs, and the riot act, the sweeping injunction granted the Forstmann-Hoffmann Co., the arrest of Weisbord and others, the refusal of President Coolidge on two separate occasions to see a committee of strikers, the strike breaking proposal to settle the strike by Secretary of Labor Davis, and the refusal of congress to act favorably on the demand for an investigation of the outrage taking place. The strike proves that the local, state and national governments serve the interests of the mill owners.

Coolidge opposes the strikers. The national administration is hostile. This is the Republican position towards the workers. The state administration, however, is equally hostile. Governor Moore is a Democrat. Recently, at Atlantic City, in spite of the fact that he was supposed to be working for a settlement, Governor Moore attacked the strike. The local government which is most vicious in its strike breaking activities is also Democratic. Passaic shows the need for a Labor Party. Passaic proves that both the two old parties are hostile to the workers.

Passaic also shows in a small way the nature of the parliamentary state. The city council of Garfield has on more than one occasion expressed its sympathy with the strikers. The councilmen are on record as protesting against the police brutality, demanding that the brutality cease and have also voted support to the demands of the workers. Nevertheless, the police brutality has been most severe in Garfield. It was in Garfield that the riot act was invoked. Garfield proves the Communist contention that behind the cloak of capitalist democracy is the grim reality of the dictatorship of the bosses.

The Passaic United Front.

Passaic has offered a very good issue for the establishment of a broad united front in support of the strike and of the issues arising out of the strike, such as defense, civil liberties, etc. The call for relief has met with a great response. The International Workers’ Aid works in very close co-operation with the strikers’ General Relief Committee. Assistance has come in from all sections of the labor and radical movement. Even the liberals have responded to the call for relief. Church organizations and petty bourgeois organizations have also responded. Relief conferences were held in many cities, well representing all sections of the labor movement. In many places branches of the Socialist Party were drawn into the conferences. At these conferences the Workers (Communist) Party played an important role in stimulating activity for the support of the strike.

The strike agitation was conducted on a broad basis. All wings of the labor movement were drawn in. Communists, Socialists, radical and conservative trade unionists united in assisting the strike. The International Labor Defense, the American Civil Liberties Union and the General Strike Committee united in defense of the strikers and the protection of their right to picket and hold meetings.

The Socialist Party, however, refused to participate in the first united front meeting held in New York in support of the strike. Norman Thomas, who had been genuinely supporting the strike and rendering the workers’ valuable services, participated in this united front thru the League for Industrial Democracy. The Passaic strike has shown us that there is a wing in the Socialist Party represented by Thomas and others which is prepared and willing to go along with the Communists in united front activities on concrete issues. Passaic proves that the more the Communists can actively participate in the struggles of the workers the better will they be able to build up united front movements and the better will they be able to draw into such united fronts the Thomas and genuine working class elements in the Socialist Party, thus isolating the reactionary right wing forces that now dominate the Socialist Party.

The Settlement Situation.

The early moves for a settlement were maneuvers on the part of the mill owners to ensnare the workers and defeat the strike. The strikers were able to recognize the true character of these early proposals and outmaneuvered the mill owners. Now there are only two committees actively engaged in working for a settlement of the controversy. The governor’s committee headed by Governor Moore and the committee headed by Judge Cabell. The Cabel committee is working for a settlement, It is not a hostile committee. This committee did not refuse to meet with Weisbord. The same cannot be said of the governor’s committee. The personnel of the committee when first announced contained two military men, since removed, whose hostility to the strikers was pronounced. In addition, the governor included the secretary of the New Jersey State Federation of Labor, Hilfers. This A.F. of L. burocrat has from the outset been openly hostile to the strike. The committee now consists of the governor, McBride, commissioner of labor, who without an investigation praised as excellent the unsanitary conditions in the mills, and Mr. Hilfers. The governor insists upon the retention of Hilfers. The reason is obvious. Hilfers is antagonistic to the strike and especially to those leading it. In the governor’s commission he can give “labor’s” approval to a settlement that will be in the interest of the bosses. At the same time he can make it possible for the U.T.W. officialdom to step in, as they have done in many instances, and make a settlement that will betray the strike. It is no surprise that the governor’s committee has taken up the cry of the mill owners against Weisbord and the United Front Committee and refuse to deal with either. The strike, however, is too well in and for the governor and Hilfers succeeding in their plan. The refusal of the governor’s committees to deal with Weisbord Was answered in no uncertain terms when ten thousand strikers waving their union cards gave Weisbord an impressive vote of confidence. Weisbord has voluntarily withdrawn from the negotiations. The strikers themselves are negotiating. The mill owners still stubbornly refuse to negotiate. The mill owners, however, will be forced to settle. The strikers are too well organized and are determined not to give in.

Passaic marks a historic turning point in the history of textile labor. This fight against starvation and inhuman conditions has set in motion a mighty movement for unity and for the organization of the unorganized. It has aroused the unorganized workers. It has inspired a spirit of militancy and solidarity in the ranks of labor. Passaic marks a step forward for the American workers. Passaic is an answer in no uncertain terms to the position of the reactionary labor burocrats and the socialists. Passaic is a warning to the powerful capitalist class of America that the fighting spirit of the American working class is not dead.

The Workers Monthly began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Party publication. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and the Communist Party began publishing The Communist as its theoretical magazine. Editors included Earl Browder and Max Bedacht as the magazine continued the Liberator’s use of graphics and art.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/wm/1926/v5n08-jun-1926-1B-WM.pdf