The story of Emil Nygard of Crosby, Minnesota was elected the first Communist mayor of the United States in 1932.

‘The First Red Mayor’ by Ben Field from New Masses. Vol. 9 No. 1. September, 1933.

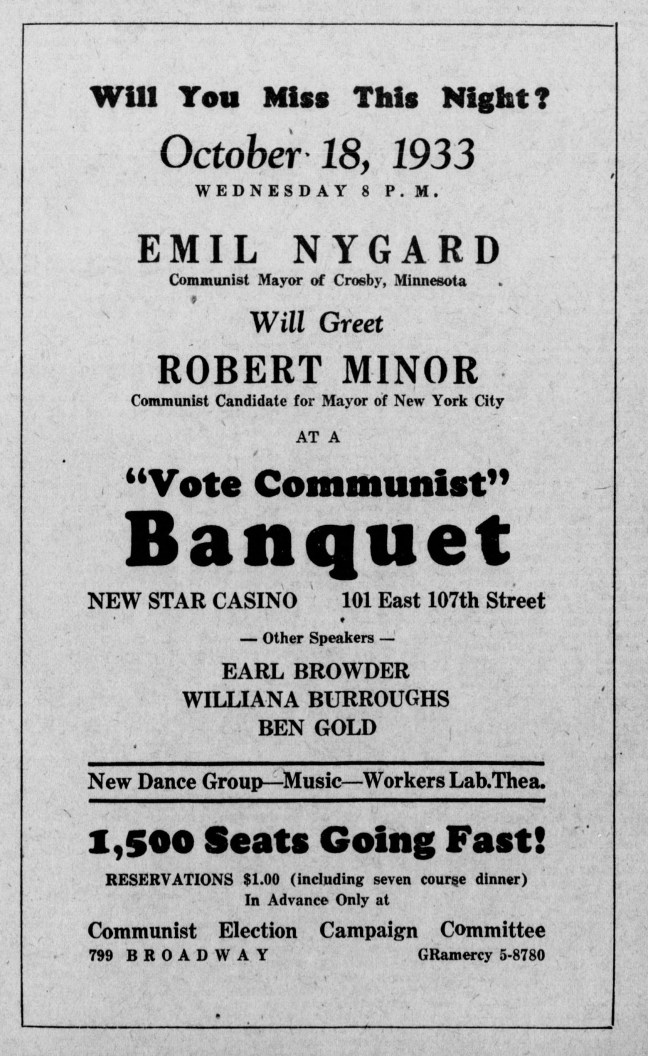

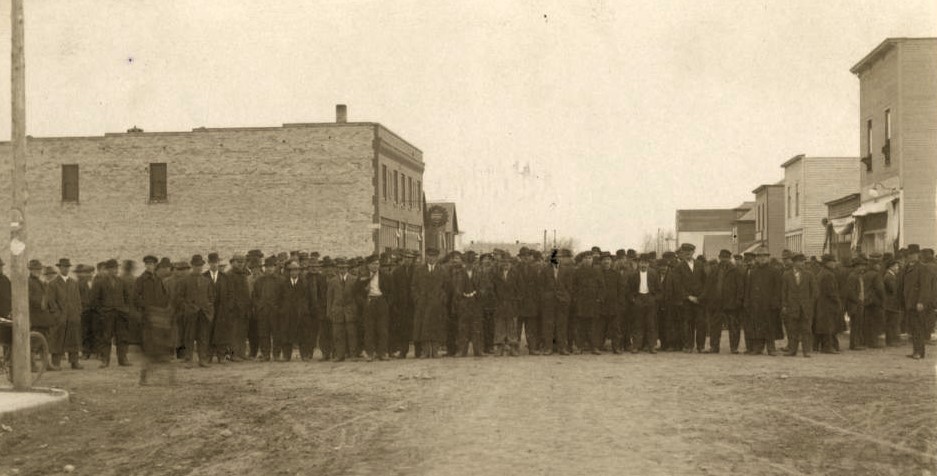

MINNESOTA was the first state to have a Hunger March of farmers. Minnesota was the first state to have a Red creamery, the Mesaba Range Creamery. The town of Crosby in Minnesota elected the first Red Mayor in the history of the country, Emil Nygard. And as the workers and farmers of America must elect other Reds in their growing struggles for bread, it is of utmost importance that we see these Crosby workers, the Mayor, the town, the Reds of Minnesota.

But Nygard is hard to bag. On our drive north we hear one day he is somewhere on the range, another day he is off to Milwaukee, a third day like a big moose he is breaking the furthest Minnesota woods. And when we do get to Crosby we are directed to the armory, from the armory to his home, and there are told he is in Hibbing, the next day to land in Duluth.

The town of Crosby looks like a thousand other onehorse towns. A main street hot and dusty in the sun. The bank. The stores plastered with raring blue eagles. The town cop with a glittering badge on the curb like a waterpump. The upper end of the town with shaven lawns and touched-up houses. And then the railroad tracks. A few rusty cars loaded with ore. A bony cow swinging her bag home. And the jobless squatting on doorsteps, their idle hands in their way.

Near the tracks we meet a miner and roadworker. He hasn’t earned more than five cents the last two months. He says, “It’ll be harder electing our Nygard this election. He’s smart. But there’s some things he could have done. He could have wiped out the damned police force. He sits home reading when he should be around with the fellows like the Socialist Mayor of Ironton. Lots of times he talks about Russia when he should be talking about conditions nearer home.”

Socialist Mayor in Ironton

That evening we meet the chairman of the unemployed council, back from picking chokecherries. We take a walk through the dark town. We sit on a bench near the lake. Arni is only in his early twenties, tall, lanky. Has worked as a pitman in the mines and in a railroad shop. Went to high school where he pitched for the school team, a southpaw. “When my control was good, they could not hit me. I went to the party school in Minneapolis. They had to tear with wild horses some of the things out of my noodle. I haven’t lost all of it yet. Here in Crosby we’ve done some things. Emil has tried hard. Sure, he’s made mistakes. So have we all, and we didn’t work together properly. But no other party would even have tried what we did. Still, we don’t understand yet what the United Front is, we don’t trust the I.W.W. when they really want to work with us, we’ve got our petty jealousies. The plenum and the Open Letter ’ll give us a good pumping. Some of our comrades may have read Marx but they don’t know Lenin. I think we can win our next elections if we go to it the right way. Iron discipline, good control, political push.” Arni, living alone, his father and mother have gone off to Alaska to earn a living. Somewhere in a tree a night bug rattles like a breaking chain. The stars burn above and in the lake.

Most of the mines around Ironton are closed. The Sagamore, a great open pit, has a few men clawing about in the water. There is a track switcher. A Bucyrus, and then a huge shovel with a five-yard bucket. Endless stockpiles.

A townsman says the Mayor is spading potatoes. We find him at last in his garden. He leans against an earthenware pot full of portaluccas. Just back from the road where the “boys” are working off their relief. A business man wanted some of the dirt. Sure, help yourself. Help yourself.

There are about 300 unemployed in Ironton. “We got some of them cutting muskeg. We’re going to have a skating rink this winter. Our population’s about a thousand.”

“Did you have a strike against forced labor?”

“No sir. In Crosby they kicked up a rumpus for nothing, thought they had the whole state by the ear. They got a good licking. Some of the Swedes and Montenegrians and such as that here in Ironton got hot under the collar too. But we cooled them off. It’s tough. I know. I work as foreman on a steamshovel when there’s work. But you’ve got to have patience. We bought wood for the unemployed. We got a truck to bring them out. Many of the boys lost their auto licenses. They can’t go for berries or wood. They can’t pay their water bills and other taxes so they take the licenses away. I got in touch with the commissioner and he said they have no right to do it. But they took them.”

“Did the town do anything about it?”

“I sent a letter.”

Only a few feet from where we are talking are the town limits of Ironton. Then you have Crosby. “We do all we can within the law. Patience is a big item. We got the truck and put up a windbreak. We bought fine stumpage for $210. Each man got 12 or 13 cords of wood.”

How about coats, boots, etc?

The stores were for giving the unemployed everything and then charging it against the relief. “We put a stop to that. We’ve got to keep our books straight. We’ve given them enough wood. In Crosby Nygard bought 80 acres of stumpage without looking at it. All jackpine. He paid $600 for it. Our stumpage was a real bargain.”

Wood, wood, wood as if the workers were woodlice, woodbeetles. And how about the NRA?

He hesitates, then: “1 think it ’ll help. Wages are going up. The Democrats are better men than the Republicans. I think Roosevelt’s really trying to help business.”

Has the town slashed wages?

“We’ve kept our books straight. I’m still getting $35. It used to be a little side money for me. But we’re better off than a lot of towns I know of. Some of the business men were afraid the companies wouldn’t re-lease the mines. They did. Most of the town is now on our side. Only one councilman is bucking me. I can handle him. And I don’t hide my beliefs.”

But he doesn’t say anything about his socialism. What is there to distinguish him from a Democrat? He just happens to be a good fellow who happens to be a Socialist and belongs to another political party. He weighs every word as if he were telling state secrets: “I believe in voting for the best man.” Yes, even if he’s Republican. Republicans and Democrats, head and tail of the same beast.

“We’re sitting pretty. We’re only bonded for $30,000. Other towns can take a leaf from our books. We’ve managed to keep the books straight. That’s a lot these days.”

We thank the courteous, middle-aged gentleman, the Socialist Mayor of Ironton, feeding his workers wood, concerned like a fat Dutch housewife, above all, in keeping things “straight.”

The Communist Mayor

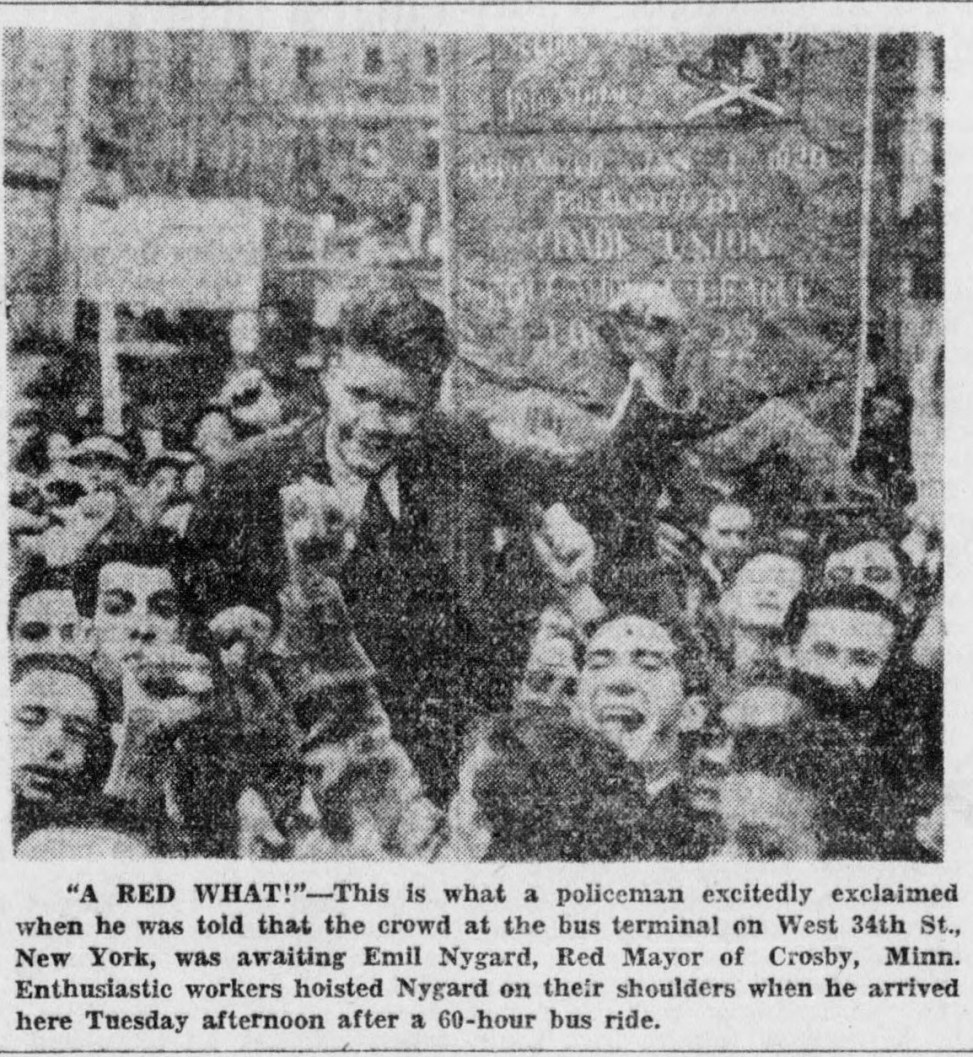

Camels Hall in Duluth is full of organizers and workers from the fields, mines, shops. A young comrade tells us about Nygard. He himself has just come out of one of the worst workhouses in the country, condemned fifty years ago, slop buckets, food so rotten his body was all covered with carbuncles and he had to be taken to the hospital. He says, “Emil’s one of the cleverest men in the movement. Minnesota has produced men like Hathaway too. In St. Paul on the Hunger March, I brought Emil to the city hall. A comrade was with us who’s a university graduate. Emil said, ‘You’ve got a higher degree. You’re a graduate of a worker’s college, a jail’. A cop tried to shove him. Emil pushed him off. When the cop found out he was the Mayor of Crosby, didn’t he turn pale. ‘Mr. Mayor, I’m a workingman too. I got to do my job. I didn’t know who you was’.”

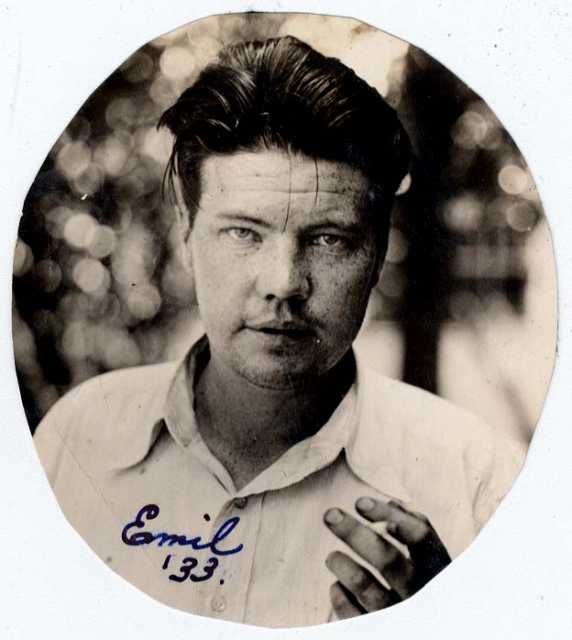

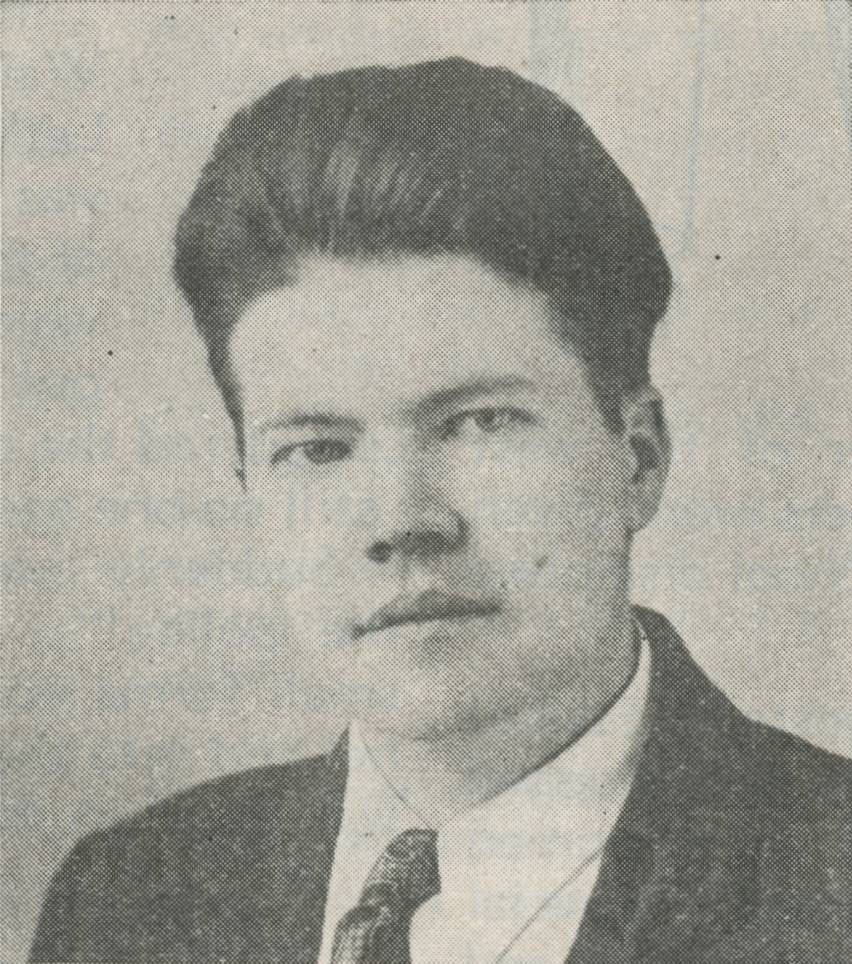

Nygard comes in. The plenum’s to begin shortly. We get into a small room. We had expected to see a tall rangy fellow like one of those blazing fireweeds from the hard Minnesota soil. Nygard admits with a laugh that he is getting fat, a Milwaukee goitre. He talks with a brogue and is freckled so that it is hard to shake off the impression he is an Irishman. His fingers are rusty looking as if from handling iron ore. He’s just bought himself a pair of shoes. The old ones are in a package in his lap.

His father, a miner, worked in British Columbia and on the Iron Range. And so when Emil was 16 the first step for him was also into the mines. Until about three years ago he took a hack at many things. Harvesting in North Dakota wheat fields, tramming timber to prop the roof the mine, loading tram cars in northern Michigan, firing locomotives in Illinois, leading a protest strike against conditions in a boarding house, trying to work his way through a university, sticking it for a year and then half-dead with hunger, firing his books into a garbage can and hopping his way home by freight.

His hair stands up for a moment like the comb of a devilish cock. “When I got back to Crosby, we started a fight to clean up the town. A clerk, a woman, had gotten away with between $3,000 and $4,000. We got our forces into the Taxpayers’ Club, a reformist organization, and took control. The club had 500 voters. A lot of small business men supported us. The unemployed council had about 300 members. Our platform was: No reduction in taxes to the mining companies. Fifteen dollars a month relief for a couple. Two dollars for each dependent, outside of clothing. Equal distribution of all municipal work. Abolition of the Police Commission. Removal of the village attorney and reduction of his salary from $100 to $50. Unemployment insurance.

“We elected three candidates, Plott, a socialist for Council, Curran a mason man for clerk, and a communist for Mayor. I got up on the street corners attacked the police and politicians and challenged them to arrest me. The Crosby Courier and Ranfier attacked Soviet Russia. Russia was dumping manganese. Our ore here is ferrous manganese. That was why there was no work. I challenged them to debate me. They didn’t show up. The last week the campaign flared up. The other side thought they had the elections sewed up. These tools of the mine owners did some digging in the foul and what explosions they came out with. They called me a boozer, a welcher, a green kid. I made a speech in which I said if what they were after was whiskers, why not import a billygoat. The Mayor running for re-election was 60. I got 529 votes as against 331 and 301. The old Mayor pulled out of town.”

Tried to Abolish Cops

Nygard takes out a box of snuff and drops a pinch into his mouth. “We forced the closed bank to release the city money. About 75% of this $23,000 went directly and indirectly into relief the first two months of the administration. The state added $5,000, and then sent a relief director here. We brought up the question of forced labor. I gave up the chair at a council meeting, and made a motion for cash relief. No other council member would vote for it at first. The presence of hundreds of workers made Plott and Hagglund vote for it. It passed. Next morning Hagglund had a heart attack. The socialist, Plott, got together with the business men and called another council meeting at 11 o’clock to reconsider the motion. They phoned me. When I got over, the hall was flooded with business men. They were ready to mob me. I voted against it. The only one. We called a mass meeting of workers. We decided on a strike. Only 11 scabs were working on the road. I went out and pulled them off. So long as I was Mayor they had nothing to fear. They would get their relief. The woman relief director raved and cried and said she would close up the office. The state director of relief came down with thugs and deputies. The R.F.C. official said it was the first time he knew of a Mayor fighting against state and town. They wanted to bribe the chairman of the unemployed council with a $125 job. He sent them to hell. At a mass meeting the director offered a compromise: 37 cents an hour for town work and 45 cents for state work. 25% of the state work to be paid in cash. He promised to raise relief to a maximum of $25 in food Value and clothing, to give more meat, even to allow the workers to trade with the cooperative. The smooth talk fooled the workers. They accepted.”

We tell Nygard about the miner’s criticism. He explains. He had wanted to abolish the police commission. The state legislature, however, had passed a law specifically aimed at Crosby preventing a Mayor from removing the police commission. Nygard had appointed in place of the tool of the mine owners a garage mechanic. The other two members are a jeweler and druggist. He cut down wages from $135 to $110. He had wanted only one policeman and the rest a worker’s volunteer corp. The council voted against him. The policemen, however, are careful now about bulldozing the workers.

They had been able to remove the village attorney, a dictator of the old lickspittle council. An attorney from Brainerd was put in his place. The bank wanted one of its own men for that job. It refused to cash warrants for the town. The town, after a while, couldn’t get the warrants cashed anywhere. The bank officials began drumming it into the heads of the workers that Nygard ’s bullheadedness would result in scrip for them. The council voted Murphy the banker in.

Nygard proposed salary cuts also for the Mayor, the clerk, and the council. His from $50 to $35, the clerk’s from $165 to $125, the councilmen’s from $40 to $25. What a howl they raised. If Nygard was willing to take a big slash, let him. As a result, the council took only ten dollars off for each one of the aldermen. They get $15 for each meeting and he $17.50. “And that’s a hell of a lot too much,” he says.

Consults Workers

We told Nygard about Ironton. “We’ve had more to buck up against. Crosby is in the hole about $135,000. We’ve got from 5 to 6 times as many jobless. Now about this timber. Four dealers got together and framed it up so that only one would bid. They jacked up from $200 to $600. I said it was preposterous to pay so much. The council said I had wanted free wood for the town and now I was against it. It was about 1500 cords of hardwood. If I voted against it, the workers would suffer. I had to vote in favor of the bid.”

We are talking in a small room that had once been a doctor’s office. Outside the plenum’s getting ready to swing into action. Bill Schneiderman, district organizer, comes in with a briefcase. He is the one who in courthouse square addressed the workers, his hands going like an oiler’s testing the heat of the great engine shanks.

“The workers of Crosby realize how I was handicapped,” says Nygard, “I’ve got a group of them as an advisory council whom I consult more than the council. They know our enemies are united against us. They weren’t fooled when the business men wanted me to keep away from the State Hunger March. ‘You know how these Reds are. You’ll get your head cracked/ But it was the town’s black eye they were mostly worried about. And the other tricks they played on us. They put the election for members of schoolboard back two days and caught us flatfooted. We had to use stickers. We did pile up quite a lot of votes for Jacobsen, once a miner, and now town gravedigger. Our fault.”

Two farm organizers pass the open door. They had been stopped in the streets by the police and ordered to leave town by nightfall. They’ll leave, however, when they are good and ready. And that is after the plenum.

“Other cities that elect our own Mayors will profit by our mistakes. The whole country’s heard about us. Why, I received 18 proposals. One from a New Hampshire girl. She wrote she didn’t know what a communist was, but if I was for the workers, I must be big-hearted.”

Nygard takes his shoes and hurries into the plenum. The ranked chairs are filled. A.U.S. Navy comrade with tattoos on his hairy arms waves his hand. Arni rushes by with a load of leaflets, a broad grin on his face. The crowded hall is dim and smoky like an engine room. Nygard is lost up front. The door closes. We go out into the throbbing city. The blue eagles with their left claws like wrenches are flattened against the store windows.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s to early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway, Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and more journalistic in its tone.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1933/v09n01-sep-1933-New-Masses.pdf