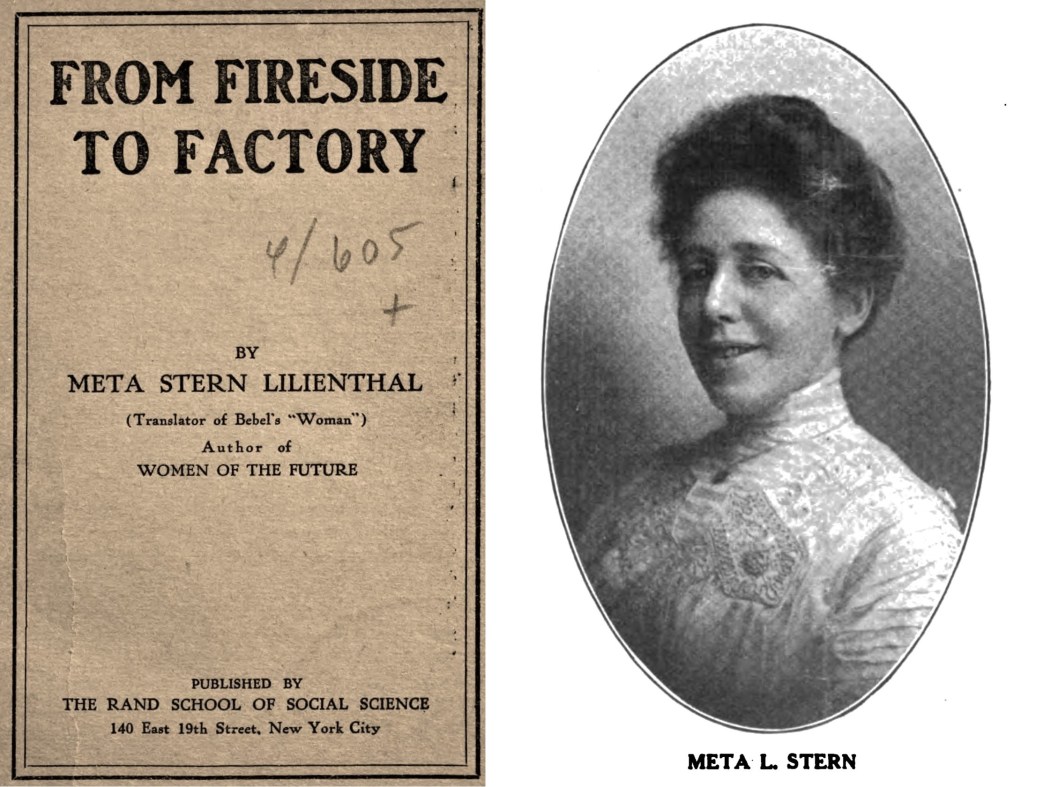

What a wonderful glimpse into the deep revolutionary workers’ tradition in the United States. Meta Lillenthal Stern, ‘Hebe,’ was among the most important women Marxists of her generation. Here she relates her personal story as a ‘red diaper baby’ born to First Internationalist parents, the comrades like Alexander Jonas and Friedrich Fritzsche she met as a child, memories of Haymarket and Henry George, and her own path to militancy and Marxism. Comrade Stern was a prolific writer and translator, best known for her effort in translating the full text of Bebel’s ‘Women and Socialism,’ was a leader of the Socialist Party’s Women’s Deportment, inspired and helped to found International Women’s Day, and was an editor of the venerable New Yorker Volks-Zeitung.

‘How This Working Woman Became a Socialist’ by Hebe (Meta L. Stern) from St. Louis Labor. Vol. 6 No. 362. January 11, 1908.

How I became a Socialist?

My story is probably different from that of the great majority of our comrades. I can not claim for myself the glory of having reasoned out Socialism, of having arrived at the conclusions of our Socialist philosophy through a gradual psychological development, for I was born a Socialist. Perhaps some of our readers may smile at this assertion, and declare they never knew that one could be born a Socialist. Still, I may reiterate my statement without feeling guilty of exaggeration, for in my case it is undoubtedly true. Long before I had the pleasure of being introduced into this world of ours, the man and woman whom I am proud to call my parents had joined the army of Socialists, a small army at that time, away back in the old days of Marx and Engels, the days of the “International,” when scientific Socialism was just becoming a recognized factor in Europe and was still a thing almost unknown in the United States. I remember Father’s red membership card of the “International.” I remember most animated conversations about Socialism around our family table, when dear friends, most of them Socialists themselves, were present. I remember the early days of our German Socialist daily, the “N.Y. Volkszeitung,” which has maintained itself successfully through all the ups and downs of the Socialist movement in America and will celebrate its thirtieth anniversary next spring. The founder and editor of the “N.Y. Volkszeitung,” Alexander Jonas, has been a lifelong friend, and I dimly recall him and my parents discussing the prospects of the Socialist paper. I remember, from their conversations, the struggles and sacrifices, the hopes and fears, the numerous defeats and the few victories in those early days, when Socialists in the United States were merely considered a handful of crazy foreigners, people either to be ridiculed or to be ignored.

When I was about six years old there was an event in my life; at that time the anti-Socialist law was in full swing in Germany, and daily I heard of the terrible persecutions of Socialists by the German government, which impressed me as the report of Russian outrages may impress our children now. The spirit of liberty, the true American spirit, was strong in me, and I admired the German Socialists who suffered imprisonment and exile for their cause. When, therefore, some of these Socialists came to New York as a delegation to enlist sympathy and collect funds to carry on their struggle, and when these men associated in our home, they became the objects of my undivided interest. One of them, F.W. Fritsche, was a fine old man with clear-cut features and a mass of gray hair that hung about his mighty head like a lion’s mane. He was a powerful agitator and a revolutionary spirit, but personally he was just a pleas- ant old gentleman. He devoted considerable attention to me and never addressed me by any other term but “Comrade,” of which I was exceedingly proud. I certainly considered myself a full-fledged Socialist then.

During my later childhood days there were three other events that have left indelible impressions. One was the candidacy of Henry George for mayor in 1886. It was the first large political enterprise of the working class of the city of New York, and my first experience in politics. My parents took me to several of the campaign meetings. I heard some of the best speakers of the labor movement of that time, and for the first time I read a newspaper, “The Leader,” a small, short-lived but enthusiastic daily paper, published by the Untied Labor Party, in the interest of Henry George’s campaign. Though a mere child, I soon achieved a pretty good under- standing of the conflict between capital and labor, and became an uncompromising partisan on the side of labor. The enthusiasm of that campaign- the most enthusiastic in my recollection, though I have taken part in many since-completely carried me away, and I recall myself standing upon a chair and shouting “George, George, Henry George,” at the top of my childish voice. I also remember how one evening, basket in hand, I went about from the ground floor to the gallery of old Chickering Hall, the favorite place for large political meetings in New York at that time, assisting in taking up a collection for campaign funds. My small size and my great ardor probably made the audience feel generous toward me. for when the baskets were turned over to the treasurer on the platform, mine was just brimful with bills and coins.

The second of the memorable events occurred to me at just about the same time. I have forgotten the exact date. It was at a large outdoor Socialist meeting on Union Square, a May Day celebration, I believe, that this event took place. Thousands of workingmen and women had come together from all quarters of the city, marching to the sound of music, carrying torches and flags and transparencies, and the banners of their unions and organizations. From the speaker’s platform where I sat with my parents I looked out upon the dense, black mass of human beings, a vast army of labor, and I remember being impressed with the apparent power and yet profound calmness and tranquility of that army. If ever a meeting was orderly and peaceable it was that in Union Square. One of the speakers had begun his address, when suddenly the farthest rows of the crowd began to quaver, and separate. The commotion continued along the lines, like ripples of water when a stone has been thrown into the calm pool, and finally the whole dense mass began to scatter in wild, disorderly flight, while shouts of “Police, Police!” rang out upon the mild spring air. What had happened? No one knew. It was so sudden, so unexpected, that it almost seemed beyond realization. We only saw men and women rushing in all directions pursued by an armed mob of police, indiscriminately and brutally using their clubs upon the heads of the fleeing multitude. I stood dumb, in wild-eyed horror. I recall how one man, who limped, and therefore received two or three blows from a policeman’s club before he could reach the platform, stretched out his hands to me and cried: “For God’s sake, Sissy, help me up!” As in a daze I assisted him to climb the platform. I remember the wild excitement, the shouting and the cries of “Shame!” “Disgrace!” “Outrage!” Later on, when comparative quiet had been restored, I remember the police captain coming upon the platform where the speakers and others were indignantly demanding an explanation, and saying something to the effect that it had been a mistake Upon that night my schooldays’ patriotism, that patriotism which pro- claimed the faultless justice and freedom of our institutions, was seriously shaken.

The third memorable event to which I have referred, one that makes me heartsick even today when I recall its dramatic incidents, is still fresh in the memory of all who are actively engaged in the Socialist movement of this country. I mean the tragedy of Haymarket Square. With painful clearness I recall the succession of events; the industrial crisis, the strike in Chicago, the conflict between union workers and scabs, the indiscriminate shooting of the police, killing and wounding many strikers, the mass meeting at Haymarket Square, the fatal bomb, the trial and the hanging of four innocent men. It was at that time that I began to understand the difference between Socialism and Anarchism; between the methods depending upon revolution and those trusting to evolution. But I understood also that although the Socialists were not in sympathy with anarchistic theories, they were battling to save the lives of men who were condemned for a crime they had not committed. They were battling to uphold justice and to prevent a judicial crime. That judicial crime was not prevented. Labor, in the United States, at that time, was still too weak and unorganized to fight an organized conspiracy of the powers of the state as it has fought successfully during the recent trial of our gallant comrade, William D. Haywood. So capitalism clutched its victims and the four men died the deaths of martyrs. But through the years ring the last words spoken by one of them: “The time will come when our silence will be more eloquent than our speeches.” Indeed, that dreary 11th day of November, 1887, has aroused the class-consciousness of thousands.

But let me return to my personal narrative. I must confess that for about ten years of my life I was only a passive Socialist. They were those years of girlhood and early womanhood, when my personal life was so strong and absorbing that it overwhelmed my interest in the broader life. First came my college days, during which I lived more in the ages of Homer and Julius Caesar than in the present-day world, and the studies of Greek and Latin and mathematics left no time for the study of live issues. I have always regret- ted those college days of mine, for I consider the years spent at conjugating Greek verbs and writing Latin compositions wasted years. I believe that the old-style classical education which fills the young mind with ossified knowledge of two thousand years ago and leaves it more or less ignorant of all the living wonders of modern sciences is a crime against life itself. An early marriage and the manifold duties of motherhood shortly followed my college days. and for years my sphere of activity was confined to the nursery. One can not go forth and give one’s time to a cause when there are little babies at home; it would not be to the advantage of society to neglect one’s babes for any cause. But the time came when my little ones no longer were babies; when they outgrew my constant care, began going to school, and began to lead individual lives of their own, leaving me time to remember that I, too, had an individuality: and then came a greater mental awakening, an unquenchable thirst. for a broader life than one limited by the four walls of home. I was still a Socialist; never, for one hour, had I abandoned Socialism: but when I began to take an active interest in the movement I had an unpleasant discovery. I realized that I did not understand Socialism, because all my life I had conceived it merely with my heart and not with my brain. At that time John Spargo, author of “The Bitter Cry of the Children,” edited a Socialist magazine called “The Comrade,” for which I furnished occasional contributions, mostly of a poetic nature. Through conversations with Comrade Spargo I began to realize that there was but one way to fully understand Socialism, and that way was to study it; and study I did. I read all available Socialist books from “the Communist Manifesto” to the most recent publications. The more I studied the more absorbed I became, the profounder grew my interest. I had always shunned economics as a dry, uninteresting study. The Rand School of Social Science, which at present affords ample opportunity for study to students of Socialism in New York, was not then in existence. But the Socialist party had arranged a course of lectures on the history of Socialism, the economics of Socialism, etc., in a small top-floor committee room, rented for the purpose, and there it was that I completed my Socialistic education. One whole year I devoted thus to study, and at the end of the year I carried a red membership card in my pocketbook and attended the meetings of my local.

Ever since I have been an active worker in the Socialist movement, and writer and lecturer for the cause. Socialism, to me, has become something more than an economic science, or a political theory; it has become a religion, a philosophy of life. My hope for the near future is that we may experience in the United States a strong movement of Socialist women, such as exists in Germany, Austria, Finland, Australia and other countries. As a Socialist I am, of course, a firm believer in the political emancipation of women. But I believe that the working woman, not the women of leisure, must accomplish this emancipation. Therefore I welcomed the coming in existence of The Socialist Woman as a hopeful sign. May it grow and prosper! May it bear the joyous message of Socialism into innumerable homes.

A long-running socialist paper begun in 1901 as the Missouri Socialist published by the Labor Publishing Company, this was the paper of the Social Democratic Party of St. Louis and the region’s labor movement. The paper became St. Louis Labor, and the official record of the St. Louis Socialist Party, then simply Labor, running until 1925. The SP in St. Louis was particularly strong, with the socialist and working class radical tradition in the city dating to before the Civil War. The paper holds a wealth of information on the St Louis workers movement, particularly its German working class.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/missouri-socialist/080111-stlouislabor-v06w362.pdf