‘’Hirsch Leckert’ at the Artef’ by Nathaniel Buchwald from New Masses. Vol. 18 No. 13. March 24, 1936.

On Freedom Square in Minsk, a monument has been erected in memory of Hirsch Lekert, the shoemaker who in 1902 made an attempt on the life of Governor von Vaal of Vilna to avenge the humiliation of his comrades whom von Vaal had ordered flogged for taking part in a May First demonstration. No less enduring than the monument of stone are two plays by two noted Yiddish poets and dramatists, A. Kushnirov of the Soviet Union and H. Levick of the United States, dealing with this memorable episode in the history of the revolutionary movement in Russia.

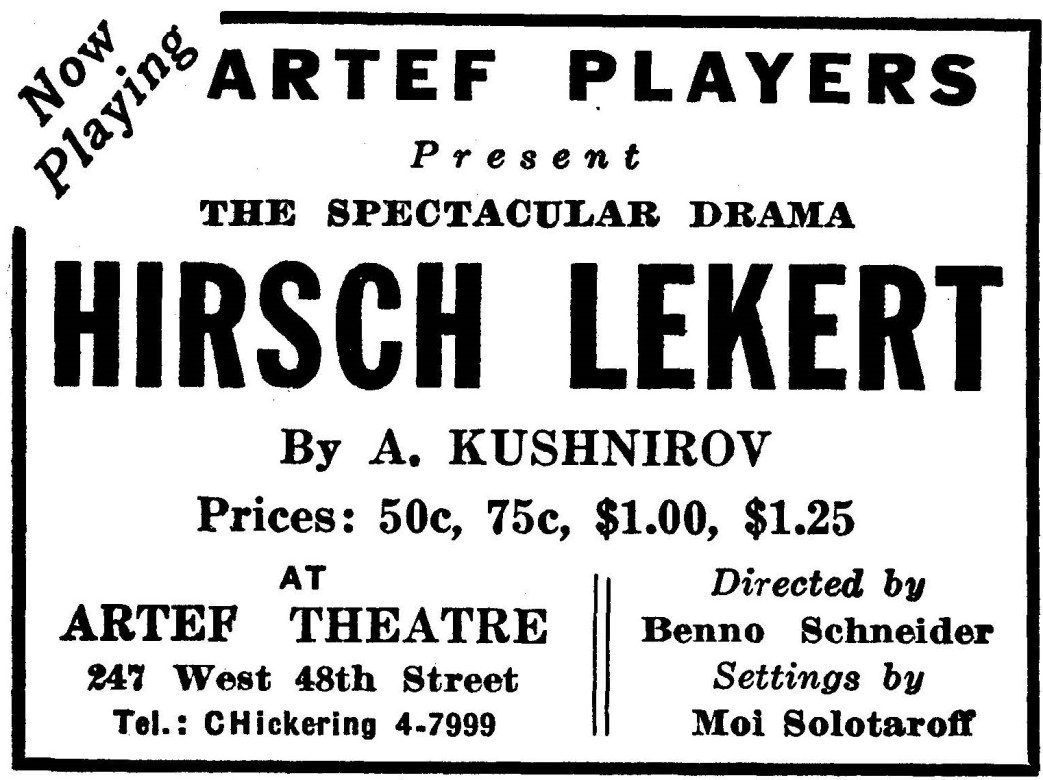

In 1932, on the occasion of the thirtieth anniversary of the execution of the revered proletarian martyr, the Artef Theater produced the Kushnirov play, which has now been revived and enriched both in direction and performance. In its current version, Hirsch Lekert is easily the best production of the Artef, Recruits notwithstanding.

In choosing Kushnirov’s rather than Levick’s Hirsch Lekert, the Artef chose political lucidity and theatrical vitality in preference to introspection and philosophic questioning. Kushnirov has admirably succeeded in portraying Lekert as a typical revolutionary worker, rather than a hero; and the martyr act of the shoemaker as the inevitable outcome of a social conflict rather than the culmination of the inner drama of the protagonist. Without sacrificing the spirit of reverence that is associated with the name of Lekert, the Soviet dramatist faithfully and with critical discernment presents the political realities of the day, the indecision of the leadership of the Bund to which Lekert adhered, the demoralizing effect of the “legal labor movement” sponsored by Colonel Zubatov of the Political Espionage in Minsk, the rising tide of revolutionary discontent and the fury of the czarist terror let loose by the von Vaals in a vain effort to stem the tide.

There is always the danger, in dramatizing social conflicts, of submerging the individual and reducing character portrayal to mere symbols of social categories. Kushnirov has escaped this danger. His characters possess a distinctiveness and individuality, while at the same time typifying the social forces at play. The plot, too, has the authenticity of historic events and the solid structure of a well made play along standard lines. While written in rhymed verse, which at times results in stilted phrasing, the dialog sounds colloquial and spontaneous.

Benno Schneider’s direction of this play is little short of perfection. This brilliant regisseur is not merely a splendid teacher and maker of actors, but also a poet and painter who composes in terms of mise-en scene, lighting effects and the elusive subtlety of rhythm. Never has Schneider achieved such blending of theatrical invention and dramatic power as in Hirsch Lekert. His bits of delightful “director’s comedy” are as dazzling as his dramatic scenes are overwhelming. The May Day demonstration is a masterpiece of craftsmanship, especially when one considers the tiny proportions of the Artef stage.

In point of individual performances Hirsch Lekert is, indeed, a new triumph for the Artef Players Collective. While M. Schneiderman in the title role may sound at times somewhat declamatory and hollow, A. Hirshbein’s performance in the role of von Vaal, S. Nagoshiner’s in the part of the colonel of the espionage department and S. Anisfeld’s. as the chief of police are truly splendid. In the lesser parts the Artef performers achieve equally effective characterizations and the ensemble is invariably good. The difference between the original production of Hirsch Lekert and the present version is a difference in acting quality and the depth and subtlety of direction. Both Schneider and his players have gone ahead in these four years.

Thus another monument has been erected to honor the memory of Hirsch Lekert. With reverence and fervor the Artef has produced a play worthy of its theme.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1936/v18n13-mar-24-1936-NM.pdf